Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Gersonides’ Scientific Interpretation of the Tabernacle

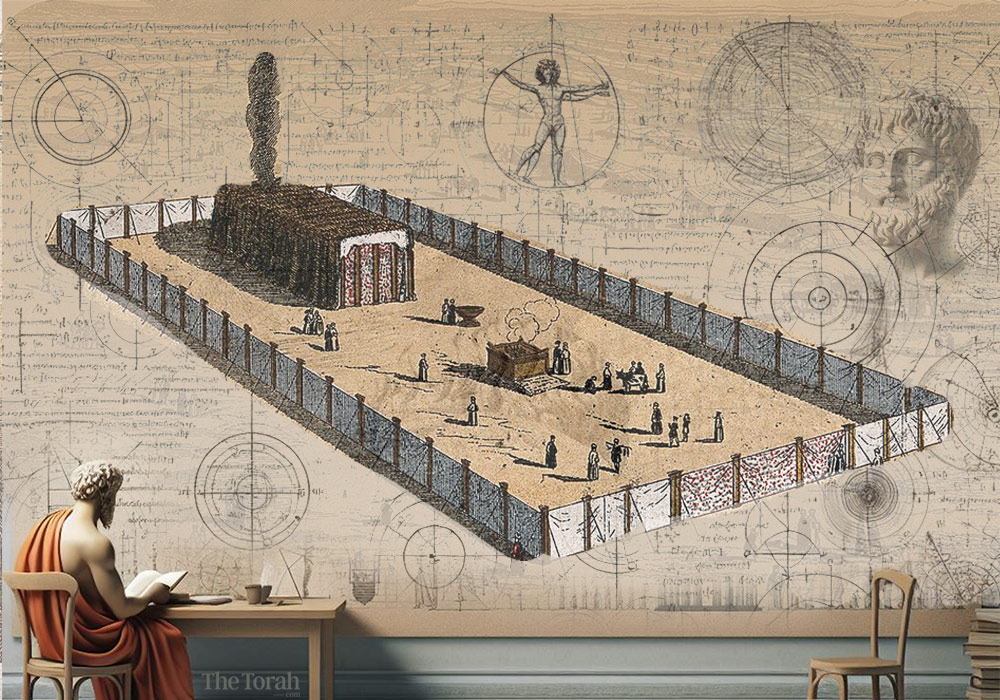

Tabernacle by William Dickes 1815-1892, Wikimedia. Adapted with AI.

Rabbi Levi ben Gershom (1288–1344),[1] known to the Jewish world by his acronym Ralbag and to the wider world as Gersonides, spent his fifty-six years in Provence.[2] While the names of his teachers remain unknown,[3] his erudition is staggering. Heavily influenced by Aristotelian philosophy, he is often considered a radical thinker.[4]

Gersonides wrote important and often groundbreaking works in biblical exegesis and halakhah, astronomy, astrology, geometry, logic, mathematics, philosophy, and philosophical theology. He also wrote extensive supercommentaries on the commentaries of Averroes (ibn Rushd, 1126–1198) on Aristotle.

Gersonides worked with Christian astronomers and astrologers and apparently enjoyed a cordial relationship with them.[5] His reputation in the wider world was such that a very large number of his scientific and philosophical works were translated into Latin[6] and his astronomical tables were sought after by Johannes Kepler.[7]

In the Jewish world, Gersonides was a controversial figure.[8] Jacob Marcaria (d. 1562), the man who first arranged for the publication of Gersonides’ major work of philosophy and theology, Wars of the Lord (מלחמות ה'),[9] admitted as much in his preface, in which he tries to defend Gersonides against detractors.[10]

Despite his controversial status, Gersonides’ commentaries on the earlier prophets and on Job were included in Bomberg’s first Mikraot Gedolot rabbinic Bible (1517–1519).[11] He also wrote a lengthy commentary on the Torah, one of the first Hebrew books to be printed (Mantua 1480), which was popular in its day, but mostly disappeared. It was republished in the modern era,[12] and can be found nowadays in many Orthodox synagogues and yeshivot.

Isaac Husik (1876–1939) went so far as to call Gersonides’ philosophical work, Wars of the Lord, a “theological monstrosity,” largely because Gersonides was willing to sacrifice God’s knowledge of particulars (i.e., knowledge of you and me) on the altar of human freedom.[13] The Torah commentary is equally philosophical, and many today might call it an exegetical monstrosity for how he connects Torah precepts hip and socket to Aristotelean philosophy. The Tabernacle is a stark example of this tendency.

Gersonides Explains the Meaning of the Tabernacle

Gersonides introduces his discussion of the meaning of the Tabernacle and its implements (Exodus 25) by stating that the benefits or lessons of the Tabernacle were meant to cover both theological ideas and social/political values,[14] whose construction calls Israel’s attention to the existence of God:

ואולם התועלת המשותף בזה הוא שזה יישיר להאמין שיש שם אלוה אדון הכל, שהוא ראוי שיעבד, כי מאתו הכל, ולזה נחוייב לכבדו מהוננו; ושהוא בתכלית הגדולה והכבוד, ולזה נעשה לו זה המקדש הנפלא ביופי ונוי וטוב התיקון;

Now, the lesson shared in this passage [by all its elements] is that it directs one to believe that there exists a God, Master of all, worthy of worship, since everything comes from Him. We are therefore obliged to honor Him with our wealth, in that He is the ultimate in greatness and honor. Thus, [we are commanded] to make this sanctuary, marvelous in beauty, decoration, in the best way possible.[15]

Gersonides then ties monotheism in with the requirement to worship God in only one place, served by only one family and tribe:

ושהוא אחד לבד, ולזה לא תהיה זאת העבודה והמקדש כי אם במקום אחד לבד, ועל ידי משפחה מיוחדת לבד והם זרע אהרן והלויים.

In that He is uniquely one, this worship and sanctuary must be in only one place, served by a special family, descendants of Aaron, and the Levites.

Before setting out to explain the significance of the Tabernacle’s individual accoutrements, Gersonides presents a philosophical introduction to the reader. He first claims that Moses was a philosopher, advanced for his time.

ונאמר, שהוא מהמפורסם למי ראה דעות הקודמים -- לפי מה שספר הפילוסוף מהם באלהיות ובטבעיות -- כי בימי משה רבינו עליו השלום היתה הפילוסופיא חסרה מאד, עד שלא נודע להם מהסיבות כי אם הסיבה החומרית, ונעלמה מהם הסיבה הצוריית, והיה זה סיבה אל שנעלמה מהם הסיבה הפועלת והסיבה התכליתיית.

We say that it is known to those who have seen the views of the ancients, as Aristotle presented them in Metaphysics and in Physics,[16] that in the times of Moses philosophy was very deficient, so much so that of all the [four] causes, only the material cause was known; the formal cause was unknown, and for that reason the efficient and final causes were [also] unknown.[17]

For Gersonides, science, knowledge of which is the key to human perfection and hence to immortality, is based upon the distinction between form and matter and the notion of a hierarchy of forms.[18] These matters are crucial for understanding physical science that, in turn, is a prerequisite for metaphysics, which teaches God’s existence. Aristotle had analyzed all physical processes into four “causes” (explanatory principles): matter, form, efficient (what we would call the immediate actual cause), and final (or purposeful). Failure to grasp this makes scientific progress impossible.

ומפני זה כלו הנה, כאשר רצתה התורה להיישירנו אל קניין השלמות האנושי, אשר אי אפשר שנקנהו אם לא בהשגת חכמת הנמצאות לפי מה שאפשר, ובהשגת מציאות השם יתעלה, הנה היישירה אותנו להאמין שבכאן צורות, הם קצתם במדרגת השלמות לקצת,

And thus, when the Torah sought to guide us to the acquisition of human perfection, which acquisition is impossible without the apprehension of physical science to the greatest extent possible, and [also] the apprehension of God’s existence, it guided us to believe that here [in the sublunary world] there are forms, some of which serve as perfection for others.

כי בזה נתיישר אל השגת סודות המציאות, ונאמין בנבואה, שיש בכאן אלוה פועל כל הנמצאות.

We thus become guided to the apprehension of the inner meaning of existence. We can then believe in prophecy that teaches that God exists, who is the cause of all existent beings.[19]

Human perfection is a function of intellectual sophistication and perfection. Since this is the only key to human immortality, the Torah serves a very important purpose. In Gersonides’ understanding, the Torah of Moses is full of hints designed to help Israelites rise to higher levels of philosophical sophistication. He illustrates this in his treatment of the Tabernacle.[20]

The Cherubs and the Active Intellect

After describing the Tabernacle in general terms (Exod 25:1–9), God instructs Moses to create the ark of the testimony (vv. 10–22), whose philosophic purpose was to serve as a base for the two cherubs placed upon it. The cherubs themselves hint at the existence of the material intellect and the so-called active (or agent) intellect[21] which makes human intellection possible:

והנה החל בצורה היותר נכבדת שבצורות אלו הנמצאות השפלות, והוא הנפש המדברת, ולזה סידר שיהיו שני כרובים על ארון העדות אשר בו לוחות הברית. והנה הכרוב האחד הוא מעיר על השכל ההיולאני, והכרוב האחר הוא מעיר על השכל הפועל, אשר פניהם איש אל אחיו, כמו שהבתאר בספר הנפש והתבאר זה עוד בראשון מספר מלחמות השם.

The Torah thus began [its description of the implements in the Tabernacle] with the worthiest of all sublunary forms, the rational soul. The Torah thus arranged that there be two cherubs on the ark of the testimony that held the tablets of the covenant. One cherub indicates the material intellect,[22] while the second indicates the active intellect, each facing the other. This was made clear in (Aristotle’s) De Anima [iii.5]) and further clarified in Wars of the Lord, treatise I [chapters 6–7].[23]

ולפי שיש גבוה עליהם ישתדלו בהשגתו כחזקת היד, רצה שיהיו פורשי כנפים למעלה, להורות על שתנועתם היא לצד המעלה, כאילו ישתדלו לעלות מזה המציאות אל מציאות יותר גבוה; וזהו האמת, כמו שהתבאר במקומותיו.

Since there exists something above them, the apprehension of which they urgently[24] seek, it was arranged that their wings spread upward, indicating that their movement is upward, as if they sought to rise above this existence to a higher one. This is the truth, as was made clear in the appropriate places.[25]

The tablets of the covenant, in this view, serve as a proof of prophecy, i.e., that the knowledge of the active intellect can be brought into the human realm:

והנה היו בארון לוחות הברית, להורות על שהגעת הנבואה איננו נמנע, אבל תהיה הגעתה אפשרית באמצעות שני כרובים האלו כמו שזכרנו בשני מספר מלחמות השם. וזה שורש גדול ועמוד חזק לקיים הגעת התורה מהשם יתעלה בנבואה, כי לולי זאת האמונה תיפול התורה בכללה.

The tablets of the covenant were in the ark, to show that prophecy is not impossible, but is made possible through these two cherubs as we pointed out in Wars of the Lord treatise II [chapters 3 and 6]. This is a great root and strong pillar establishing that the Torah came from God through prophecy, for without this belief, the entire Torah would collapse.[26]

The Tabernacle Implements and Their Philosophical Meaning

Gersonides devotes detailed attention to the ark, table, menorah, curtain, copper altar, and incense (golden) altar.[27] In his discussion, he cites various works by Aristotle (On the Soul, Physics, Metaphysics, On Animals, Parva Naturalia) and by himself (Wars and his commentary on Song of Songs), but not Maimonides nor the Talmud (or any other halakhic source or work).

The curtain (parokhet) dividing the holy from the holy of holies (Exod 26:31, 33) indicates the distinction between the material forms, symbolized by the table and the menorah, and the incorporeal forms. The study of the forms of material things (i.e., the physical sciences) leads us to the apprehension that in the sublunar world there is an intellect that perfects us, bringing our intellects from potentiality to actuality. We are also led to apprehend that this “active intellect” is not God.

The table (shulchan) indicates the nutritive soul.[28]

The lampstand (menorah) indicates the sensitive soul.[29] Since the latter is worthier than the former, the lamp is placed in the south [yamin], and the table in the north, since the right [yamin] is worthier than the left.[30]

The ark of testimony is in the west; if it were in the east, people might think that the sun is God.

The altars of gold and brass indicate corruption[31] and thus have four corners [horns], symbolizing the [four] elements out of which all material elements are made.[32] The brass altar indicates the corruption of all entities that have no immortality, while the golden altar, the corruption of human beings who can achieve immortality. Burning incense, offered on the altar of gold, has greater fragrance than unburned incense:

וכן הענין בנפש המדברת, רוצה לומר כי בהִפָּרְדָהּ מהאדם תִּמָּצֵא יותר חזקה בפעולתה - והיא ההשגה - ממה שהיתה בהִדָּבְקָהּ עם החומר, להִנָּקוֹתָהּ משאר כוחות הנפש המונעות אותה מלהשתמש בהשגתה.

This is similar to the rational soul: its activity, i.e., rational apprehension, is strengthened when it is divorced from matter, since it is cleanly separated from the other powers of the soul, which restrain it from using its apprehension.

The shewbread—Six loaves were on the western side, near the ark, and six on the eastern side, near the two altars, in order to teach ענין נפלא, שהוא מהגדולות שבפינות העיוניות והתוריות “a wondrous matter, among the greatest cornerstones of philosophy and of the Torah”: that sublunary existence is influenced by the astral spheres [galgalim], which maintain existent beings as they are.[33] Further on in his commentary, Gersonides makes clear that there are precisely 12 loaves—and not 14 as one might have expected if it was based on two loaves per day of the week—to indicate the twelve heavenly constellations (as numbered by medieval astronomers).

An Entirely Aristotelian Commentary

Gersonides ends his account of the ark, table, and menorah with the following statement:

הנה זה הוא מה שנראה לנו בענין הארון והשולחן והמנורה, והוא נפלא מאד ומעיד לעצמו מכל צד ומכל פינה שזאת היתה הכונה בהם.

This is what we have seen fit explain concerning the ark, table, and menorah; it is very wondrous and testifies to itself from every aspect and every vantage point, that this is their intention.

At the very end of his commentary on Exodus, Gersonides reiterates this claim, by explaining that the reason the Torah entered into so much apparently redundant and excessive detail[34] was to draw us into the study of the philosophical lessons about the universe that he discovered in the Torah’s account:

שכבר למדנו בזה ההכפל שכל הדברים שנזכרו בזאת המלאכה הם מכוונים

We learn from this doubling that all of the matters used to describe the work [of constructing the Tabernacle] are intentional.

For Gersonides, this was an important indication that he read his allegorical interpretations out of the text, not into it.[35] At the same time, he ends up proving himself a commentator whose exegesis is unlikely to resonate with contemporary readers.

Taking Gersonides at his word, as we should, we can understand why his Torah commentary apparently fell out of favor by the end of the Middle Ages. Galileo, Newton, Copernicus, et al. showed the falsity of the physics of the four elements, each with its natural place, the heavens as qualitatively different from the “sublunar” realm, living planets held in place by heavenly spheres (galgalim), etc. With that, Gersonides’ world was turned upside down and inside out, and his explanation of the mishkan became nothing more than a historical curiosity.

Reading him today, we find a great Talmudist and a great philosopher struggling to make sense of the sanctuary in the wilderness and, by implication, of the Temple in Jerusalem. Yet his reading is not one that crosses the threshold easily from his Aristotelian world into our own.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 13, 2024

|

Last Updated

March 26, 2024

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Footnotes

Prof. Menachem Kellner was founding chair of Shalem College’s Interdisciplinary Program in Philosophy and Jewish Thought. He is Emeritus Professor of Jewish Thought at the University of Haifa, where, among things, he held the Sir Isaac and Lady Edith Wolfson Chair of Religious Thought. He did his B.A, M.A. and Ph.D. at Washington University. Kellner is probably best known for his book, Must a Jew Believe Anything? His most recent book is We are Not Alone: A Maimonidean Theology of the Other (Boston 2021).

Essays on Related Topics: