Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Birth on the Knees

A ceramic childbirth scene, by the Karajà indigenous people, 1980. Muséum de Toulouse, Brazil. Wikimedia

When Job, bereft of family and property and stricken with illness, curses the day of his birth, he asks:[1]

איוב ג:יא לָמָּה לֹּא מֵרֶחֶם אָמוּת

מִבֶּטֶן יָצָאתִי וְאֶגְוָע.

Job 3:11 Why did I not die from the womb—

exit the belly and perish?[2]

Job continues:

איוב ג:יב מַדּוּעַ קִדְּמוּנִי בִרְכָּיִם

וּמַה שָּׁדַיִם כִּי אִינָק.

Job 3:12 Why did knees meet me,

and why breasts that I sucked?

The final line is a clear reference to the mother breastfeeding, but whose knees are these, and what image does this question evoke?

1. The Father Places the Child on His Knees

Some interpreters have claimed that the knees belong to the father, who receives the recently born child and places it on his knees in an act of legal recognition. Such a practice is suggested by the description of Joseph’s great-grand-children being born on his knees:[3]

בראשׁית נ:כג וַיַּרְא יוֹסֵף לְאֶפְרַיִם בְּנֵי שִׁלֵּשִׁים גַּם בְּנֵי מָכִיר בֶּן מְנַשֶּׁה יֻלְּדוּ עַל בִּרְכֵּי יוֹסֵף.

Gen 50:23 Joseph lived to see children of the third generation of Ephraim; the children of Machir son of Manasseh were likewise born upon Joseph’s knees.

A similar custom, known as sublatio or tollere, in which the father lifts the child to signal his acceptance of it into his household, is well-attested in Roman and Greek sources.

This interpretation, however, introduces the father into the scene of Job’s birth, though he is never mentioned in the surrounding verses or in the chapter as a whole. Moreover, nothing in the Bible suggests that a father would place a child on his knees to signal the child’s acceptance as his legitimate offspring.

In addition, from a historical point of view, the presence of a father at the birth of their child is a rather rare phenomenon. Only in the last decades has it become a widespread custom in many countries around the globe. In ancient Israelite society, however, fathers would not typically have been present at birth, at least according to Jeremiah:

ירמיה כ:טו אָרוּר הָאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר בִּשַּׂר אֶת אָבִי לֵאמֹר יֻלַּד לְךָ בֵּן זָכָר שַׂמֵּחַ שִׂמֳּחָהוּ.

Jer 20:15 Accursed be the man who brought my father the news and said, “A boy is born to you,” and gave him such joy!

Finally, it makes little sense for Job to include the father in his wish that he had died at birth, since the father would not have been as important to the survival of the newborn as the mother.[4]

2. Father or Midwife Kneels to Receive the Child

Based on ethnographic studies among Arab Bedouin tribes carried out in Transjordan at the beginning of the 20th century, some scholars posit that the image is that of the father kneeling in front of the parturient woman to receive the child.[5] This solution is also implausible. Aside from the time span between the composition of Job (4th century B.C.E., at the latest) and these studies, the studies suggest that the practice was atypical, citing only one tribe where the man was supposed to kneel in front of his wife during childbirth.[6]

More plausible is that a midwife or another type of female helper would be kneeling in front of the parturient woman.[7] Anthropologists have noted that very few contemporary peoples know of childbirth without a female attendant, and this would hold true for ancient societies as well.[8]

Nevertheless, the introduction of a midwife seems strange in the context of a passage that is otherwise focused on the child’s interactions with the mother’s body. Moreover, if the first person that the infant encounters outside of the womb is the midwife, it would more probably be her hands or arms rather than her knees that the infant encounters.

3. The Mother Is Sitting on Someone’s Knees

Citing the story of Rachel and Bilhah, others argue that the verse suggests that the parturient woman is giving birth while sitting on someone’s legs:[9]

בראשׁית ל:ג וַתֹּאמֶר הִנֵּה אֲמָתִי בִלְהָה בֹּא אֵלֶיהָ וְתֵלֵד עַל בִּרְכַּי וְאִבָּנֶה גַם אָנֹכִי מִמֶּנָּה.

Gen 30:3 She said, “Here is my maid Bilhah. Consort with her, that she may bear on my knees and that through her I too may have children.”

The phrase, וְתֵלֵד עַל בִּרְכַּי, “bear on my knees,” however, is likely idiomatic and would not describe the actual physical process of childbirth taking place on Rachel’s knees. It might figuratively refer to an act and maybe even to a rite of adoption. Or it may refer to no custom at all, but to the intended effect: If the child is legally Rachel’s, then she would be the one to hold it on her knees, caressing and taking care of it.

In addition, if Genesis is referring to adoption or a similar legal institution, that custom would have no bearing on the interpretation of the birth scene in Job.

4. The Mother Puts the Child on Her Knees

Others suggest that the image of the knees refers to maternal care and/or nursing.[10] Proponents often cite the example of the Assyrian king Assurbanipal nursing on the knees of the goddess Ishtar (whose temple was in the city of Nineveh):

COS 1.145, rev. 6–8 You were a child, Assurbanipal, when I left you with the Queen of Nineveh; you were a baby, Assurbanipal, when you sat on the lap (lit.: “knee”)[11] of the Queen of Nineveh! Her four teats were placed in your mouth: two you would suckle and two you would milk before you.[12]

In addition, ancient Egyptian iconography contains numerous examples of Isis lactans statuettes or amulets, which depict a seated Isis with an infant Horus sitting on her knees and nursing from her breast. Many amulets and scarabs of this image have been found in the Levant, dating to well into Persian times.[13]

Yet the only parallel in the Bible that depicts a mother holding her own child on her knees involves an older child about to die!

מלכים ב ד:כ וַיִּשָּׂאֵהוּ וַיְבִיאֵהוּ אֶל אִמּוֹ וַיֵּשֶׁב עַל בִּרְכֶּיהָ עַד הַצָּהֳרַיִם וַיָּמֹת.

2 Kgs 4:20 He picked him up and brought him to his mother. And the child sat on her knees until noon; and he died.

Moreover, this interpretation fails to reckon with the Piel verb קדם in our verse: מַדּוּעַ קִדְּמוּנִי בִרְכָּיִם, “Why did knees meet me?”

The verb often conveys the sense of the subject explicitly moving towards the object, facing it.[14] From the child’s perspective, this suggests a dynamic process in which someone’s knees move towards the child. This is not consistent with the rather static image of a child being breastfed. It is, however, consistent with an image of birth.

5. A Kneeling Birth Position

Our Western culture is pervaded by the mental prototype of childbirth in the supine position.[15] A short perusal of various movies and TV/internet series is enough to recognize this very narrow and recurring pattern.

This scene is usually set in a hospital, often with precautions that one would expect in an operating room—medical gloves, surgical masks and a sanitized environment. Most significantly, the parturient woman herself is always lying on her back, even when she is giving birth far from any civilized context.[16]

This image of childbirth is, nowadays, deeply rooted in Western, medicalized culture.[17] Thus, someone reading “Why did knees meet me (face first)?” and imagining a woman in childbirth, lying on her back, knees bent above her belly, will hardly be able to imagine how the two—the infant and the knees—should ever meet.

The image only makes sense if it reflects a different position for the parturient mother: upright and kneeling. A newborn exiting the womb from this position would automatically turn to the side and come to rest on the floor between the legs of the mother, facing her knees.[18] From the perspective of the newborn, expulsion from the womb would seem as if the knees of the mother were approaching to meet it.

Birthing Practices in the Ancient World

Women in childbirth in antiquity are hardly ever depicted lying on their backs.[19] On the contrary: they are portrayed as standing, sitting, crouching, squatting, using a birth stool,[20] or—relevant to our purposes here—kneeling.[21]

Ugarit

In a mythic text found in Ugarit’s famous library (ca. 13th–14th c. B.C.E.), the god El commands two women:

KTU 1.12 I 14-27 “Place the bricks, go into labour and bear (jld) the Eaters, let her kneel (brk), and bear the Devourers.”[22]

The language of this myth is difficult and the text defective. Nevertheless, giving birth is clearly connected with kneeling; the root b.r.k is the same as ב.ר.ך in Hebrew.

Egypt

A hieroglyph for birth-giving – A hieroglyph for “giving birth”—known as early as in the third millennium B.C.E, but attested for several later dynasties—shows a kneeling woman, beneath which the head and arms of an infant appear.[23]

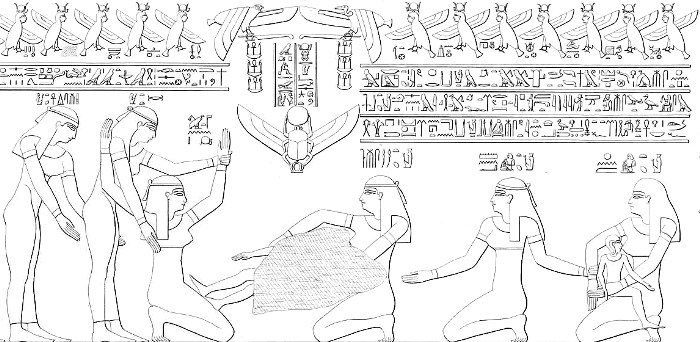

Relief of the solar goddess Raet-Tawy and her son, Horus-pa-Re-pa-kheredin, from the birth house of Hermonthis (Lepsius, Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien, plate 60).

The birth house in Hermonthis – A relief in the birth house of Hermonthis (modern Armant), a temple dedicated to the local solar goddess Raet-Tawy and her son, the young sun god Horus-pa-Re-pa-khered (=Harpre), shows the goddess kneeling on the ground, with the infant god being drawn from her by a divine midwife. The scene is flanked by more divine midwives and wet nurses, the divine father of the child, Amun-Re, and the goddess Nekhbet.[24]

Cyprus

Among the many examples from the region of Greece and Rome is a very early figurine from the chalcolithic period (4th–3th millennium B.C.E.) found in Paphos. The small, 1.5-inch tall, dark grey picrolite figure depicts a kneeling woman, naked, with a swollen belly held by her two hands. She likely represents a goddess, and the figurine may have served as an amulet during parturition.[25]

Though the items discussed here are from different areas and periods, all feature a kneeling position that typified ancient births and that likely lies behind the image in Job.

Biblical Evidence: Eli’s Daughter-in-Law

The brief account in which the priest Eli’s daughter-in-law gives birth suggests a similar birth position:

שׁמואל א ד:יט וְכַלָּתוֹ אֵשֶׁת פִּינְחָס הָרָה לָלַת[26] וַתִּשְׁמַע אֶת הַשְּׁמֻעָה אֶל הִלָּקַח אֲרוֹן הָאֱלֹהִים וּמֵת חָמִיהָ וְאִישָׁהּ וַתִּכְרַע וַתֵּלֶד כִּי נֶהֶפְכוּ עָלֶיהָ צִרֶיהָ.

1 Sam 4:19 His daughter-in-law, the wife of Phinehas, was pregnant, about to give birth. When she heard the news that the ark of God had been captured, and that her father-in-law and her husband were dead, she knelt down and gave birth, for her contractions had come upon her.

The verb וַתִּכְרַע is often translated as “she went into labor,” “she bowed down,” “she crouched down,”[27] or “she broke down,” but the basic sense of the Qal verb כרע is “to kneel” or “to kneel down.”[28] For example, YHWH declares: לִי תִּכְרַע כָּל בֶּרֶךְ, “to Me, every knee shall kneel down” (Isa 45:23). Similarly, when Solomon finishes praying at the dedication of the Temple, he rises up, מִכְּרֹעַ עַל בִּרְכָּיו “from kneeling on his knees” before YHWH’s altar (1 Kgs 8:54).[29]

Thus, the image in the narrative of Eli’s daughter-in-law is of a woman kneeling down to give birth. Equally, the image behind Job 3:12 is one of Job’s mother giving birth on her knees.

Two Different Stages of Life, Not One

Once the birthing position is recognized, the intent of Job’s curse on the day of his birth becomes clear. He begins with a wish:

איוב ג:יא לָמָּה לֹּא מֵרֶחֶם אָמוּת

מִבֶּטֶן יָצָאתִי וְאֶגְוָע.

Job 3:11 Why did I not die from the womb—

exit the belly and perish?

These lines are often misunderstood as synonymous references to death after birth.[30] The prepositional phrase מֵרָחֶם (literally “from the womb”), however, indicates that the child is in the womb at death, as Jeremiah’s curse on the man who brought news of his birth to Jeremiah’s father makes clear:

ירמיה כ:יז אֲשֶׁר לֹא מוֹתְתַנִי מֵרָחֶם וַתְּהִי לִי אִמִּי קִבְרִי וְרַחְמָה הֲרַת עוֹלָם.

Jer 20:17 Because he did not kill me from the womb so my mother would have been my grave, and her womb pregnant forever.

Thus, Job’s wish references two different stages of life: 1) a miscarriage or stillbirth in the first line;[31] and 2) a live birth that ends with a neonatal death in the second.[32] Likewise, the next verse represents two different life stages, in this case, birth and breastfeeding:

איוב ג:יב מַדּוּעַ קִדְּמוּנִי בִרְכָּיִם

וּמַה שָּׁדַיִם כִּי אִינָק.

Job 3:12 Why did knees meet me,

and why breasts that I sucked?[33]

Job’s curse offers a logical chain of parallelisms, in which each bicolon refers to missed opportunities for an early death in two different stages of life: miscarriage/stillbirth vs. neonatal death (v. 11), and death at birth vs. death from lack of breastfeeding (v. 12).[34]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 11, 2025

|

Last Updated

January 4, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Juliane Eckstein is an Interim Professor of Catholic Theology/Religious Education at the Pädagogische Hochschule Freiburg [College for Education] in Southwestern Germany. She received her PhD from the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich, and she previously taught at the Johannes Gutenberg-Universität in Mainz, at the Ruhruniversität Bochum, and at the Philosophisch-Theologische Hochschule Sankt Georgen. She is the author of Die Semantik von Ijob 6-7: Erschließung ihrer Struktur und einzelner Lexeme mittels Isotopieanalyse [The Semantics of Job 6-7. Interpretation of Its Structure and of Individual Lexemes Using Isotopy Analysis] (Mohr Siebeck, 2021).

Essays on Related Topics: