Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Lot’s Wife Turns as an Act of Resistance: The Art of Yehuda Levy-Aldema

Levy-Aldema's artwork on the eight waws in Genesis 19:24–26.

The Fate of Lot’s Wife in Art

The moment of “his wife” becoming a pillar of salt, as she, her husband, and two daughters escape the destruction of Sodom, has attracted the attention of artists throughout the ages. The moment that transforms her from a human being to a mineral is told in six Hebrew words in Gen. 19:26:

בראשׁית יט:כו וַתַּבֵּט אִשְׁתּוֹ מֵאַחֲרָיו וַתְּהִי נְצִיב מֶלַח.

Gen 19:26 And his wife looked from behind him and she became a pillar of salt.

Many artists combine the dramatic scene of the transformation of Lot’s wife with Sodom’s destruction by fire. Earliest visual depictions of this scene appear in illuminated Bible manuscripts and Passover Haggadot. A few paintings from art history illustrate how different the traditional artistic focus is compared to the seven sculptures of Levy-Aldema.

The renowned Nuremberg Chronicle, an illustrated encyclopedia from 1493,[1] depicts the destruction of a medieval-looking town of Sodom.

Sodom and Gomorrah in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

Sodom and Gomorrah in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

“His wife” appears as a white cone at the center of the image, her head still turned toward the city. An angel guides Lot and the two daughters, dressed in medieval garb, away from the destruction.

In “Sodom and Gomorrah Afire” (1680), Jacob de Wet presents the main characters at the lower center of the painting—Lot, his two daughters, and two angels—far from the burning city, while the wife, standing near it, blends into the gold-brown-yellow color scheme.

.jpg?alt=media&token=4dba4a10-78e3-42af-a2d1-b309ee1f7669) Sodom and Gomorrah Afire by Jacob de Wet II (1680)

Sodom and Gomorrah Afire by Jacob de Wet II (1680)

Many other works of the medieval and later periods in Western art offer similar portrayals.[2]

Contemporary Depictions of the Scene

The German painter and sculptor, Anselm Kiefer (b. 1945), created a famous painting, entitled Lot’s Wife, in 1989. Known to be arguing with controversial issues, including the Nazi era, Kiefer painted train tracks instead of a human figure. His painting presents not a woman but the imagined object of her gaze. She looks back to the concentration and death camps of the Holocaust, a contemporary version of Sodom and Gomorrah.

|

|

Another famous contemporary artist, Kiki Smith (b. 1954), built a sculpture, entitled Lot’s Wife, in 1997. The work presents a semi-naked female figure with her head turning, perhaps unnaturally far backwards to the left. The woman’s clothes seem to be in the process of disassembling and her feet are already gone.

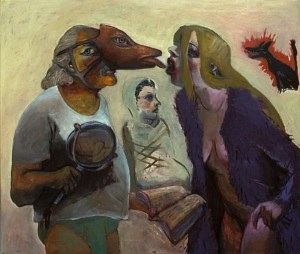

The Dutch painter and print maker, Marcelle Hanselaar (b. 1945), painted a three-figure scene, entitled “Lot’s Wife,” in 2004. The painting shows three figures with Weimar Republic visual resonances. The middle figure in white is the wife, seemingly bound with brown ropes around her chest and arms, perhaps hinting at her inability to intervene.

She is surrounded by a male figure on the left who wears a dog-faced mask and only a t-shirt and green underwear. He also carries a magnifying glass and a book under his right arm. On the right side is another female figure with long yellow hair, dressed with a purple bathrobe and otherwise naked. The dog-faced mask of the man stretches the tongue toward the mouth of the blond woman who is almost receiving it. On the red upper corner is a black dog surrounded by red paint, perhaps hinting at the sexual aggression emanating from the scene.

The painter and printmaker, Rachel Clark, created an abstract painting on “Lot’s Wife” in 2009. The painting features a white swirling cone in the middle of the canvas, dividing the right from the left side. The white cone is probably the wife in the process of becoming a pillar of salt.

The right side consists of deep red tones, with a few black marks on the upper part, perhaps hinting at smoky fires. The left side is brown, painted in horizontal broad strokes, seemingly leading from a brighter to a darker, perhaps shaded path. Is this the path toward the cave that her daughters and husband will later take?

Lot’s Wife in Nature

Rock formations in Japan and near the Dead Sea have been named in her memory.[3] These rocks are not necessarily white like salt, but the geological shape always resembles a pillar. A Japanese rock, coming straight out of the Philippine Sea, reminded a British sailor, John Meares, of Lot’s wife in 1788. A geological pillar formation near the Dead Sea has been identified as “Lot’s Wife.” Already the Jewish historian Josephus claimed to have seen the pillar of salt attributed to Lot’s wife, as well as early church fathers, such as Clement of Rome and Irenaeus.

|

|

Yehudah Levy-Aldema’s Sculptures on the Transformation of “His Wife”

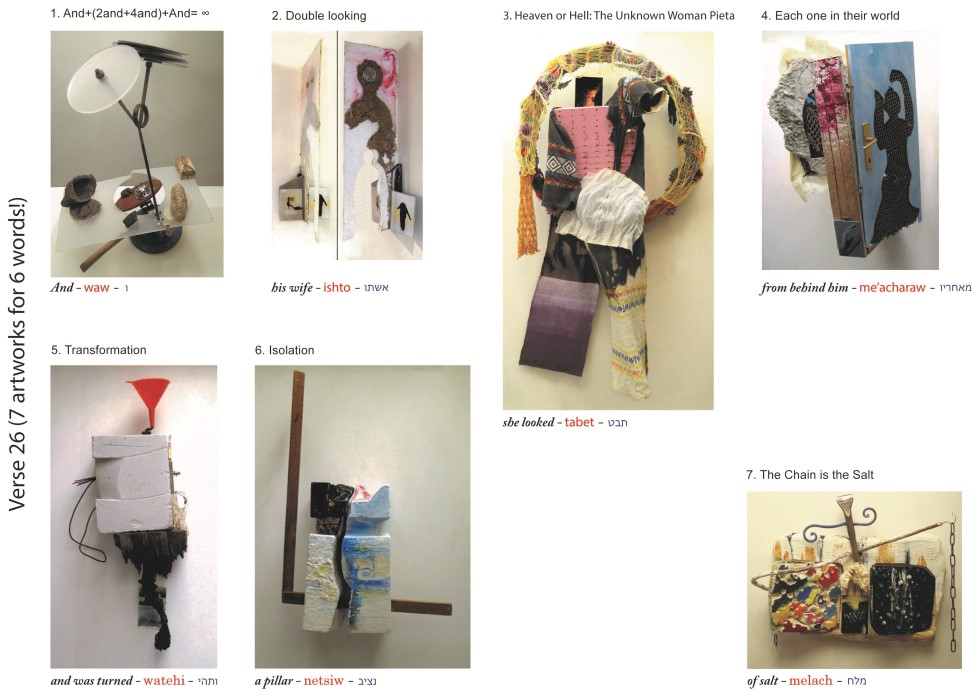

The Israeli Jewish-orthodox artist Yehuda Levy-Aldema (b. 1957) has chosen a very different approach. He created seven sculptures[4] all of which are based on the single verse: one sculpture for the first Hebrew letter, a (prefixed) waw, and six sculptures for the six Hebrew words of the verse, וַתַּבֵּט אִשְׁתּוֹ מֵאַחֲרָיו וַתְּהִי נְצִיב מֶלַח “And his wife looked from behind him and she became a pillar of salt.”

The seven conceptual and abstract sculptures require additional explanations to elucidate the meanings of the artworks, just like other contemporary conceptual and abstract art.[6] Each sculpture is human-sized: 1–1.5 meters (5 ft) long, 70–90 centimeters (2.2–2.95 in) wide, and 30–50 centimeters (1–1.6 ft) deep. Six sculptures attach to the wall at eye level and one artwork, related to God, is free-standing.

All sculptures consist of wood, industrial materials, iron, paper, stone, rocks, pieces of furniture, or familiar household items, and are non-perishable, organic, and non-organic, often fragile materials. The materials were found in nature, left behind garbage containers or abandoned in the streets, or they were donated to the artist by friends or family members.

The artist always selects ordinary objects, found or discarded, to transform the materials into his artworks. They speak about ordinary human life in connection with his interpretation of the Bible. The sculptures produce what biblical scholar J. Cheryl Exum envisions for art on the Bible: “a genuine dialogue between the Bible and art…in which the biblical text and biblical art play an equal and critical role in the process of interpreting each other.”[7]

Since Levy-Aldema interprets Sodom and Gomorrah for the Here and Now, he did not select the two-dimensional medium of painting but created three-dimensional sculptures. The sculptures on verse 26 invite viewers to explore the miraculous process in which “his wife” is transformed from human life into the inorganic matter of salt. All seven artworks empathize with her last living moment. They read the verse from her perspective.

Of his creative process, Levy-Aldema says: “I need to justify everything I do in the artwork.”[8] To that end, the artist consults Jewish and Christian interpretations, grounds his ideas within global and Western art, gathers cross-cultural information online, and confers with interdisciplinary scholarship.

He also speaks with a small group of conversation partners, in regularly scheduled havrutot (learning together with a partner), to deepen his understanding about what he wants to convey with his sculptures. In the end, every nail, color, cloth, shape, and form communicates meaning; no element is accidental, unintentional, arbitrary, or mere decoration.

Each of the seven sculptures is visually dramatic and enigmatic. Each sculpture also differs greatly from the other, but all of them rely on the same visual grammar. They invite viewers to ponder how and why “his wife” turns into a pillar of salt. We will focus here on the first sculpture only.

The First Sculpture: Waw, the Tetragrammaton, and the Shekhinah

|

#1: “AND+(2and+4and)+And=∞” Materials: Plexiglas platform, 7 Plexiglas mirrors, iron disc, a wheel of a fitness bike, car jack, Ammonite fossil, scoria volcanic rock, wooden box, metal axe, acrylic color, 6 bolts, base and a cover of a table lamp, 2 blue beads, and a photograph. 70x63x100 cm. |

The title of the first sculpture, which reads like a mathematical equation, hints at its theme: “AND+(2and+4and)+And=∞.” The eight “ands”[9] in the title refer to the seven prefixed waws in Genesis 19:24–25 and the first prefixed waw in 19:26:

בראשׁית יט:כד וַי־הוָה הִמְטִיר עַל־סְדֹם וְעַל־עֲמֹרָה גָּפְרִית וָאֵשׁ מֵאֵת יְ־הוָה מִן־הַשָּׁמָיִם. יט:כה וַיַּהֲפֹךְ אֶת־הֶעָרִים הָאֵל וְאֵת כָּל־הַכִּכָּר וְאֵת כָּל־יֹשְׁבֵי הֶעָרִים וְצֶמַח הָאֲדָמָה. יט:כו וַתַּבֵּט אִשְׁתּוֹ מֵאַחֲרָיו וַתְּהִי נְצִיב מֶלַח.

Gen 19:24 And YHWH rained upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from YHWH out of heaven. 19:25 And [YHWH] annihilated those cities and the entire Plain, and all the inhabitants of the cities and the vegetation of the ground. 19:26 And his wife looked from behind him and she became a pillar of salt.

The sculpture suggests that God initiated the wife’s acceptance of death at this particular moment. Levy-Aldema thus asserts that “God is in the [first] waw”[10] of Gen. 19:26. This waw stands in a row of waws that appear in verses 24-25 reporting on the divine destruction of Sodom.

In verse 24, the waw is joined to the tetragrammaton (וַי־הוָה), and thus the sculpture’s title represents this waw in capitalized letters, “AND.” Verse 24 has two more waws and verse 25 has four, leading to the formulation in the title “(2and+4and).” The final “And” in the title represents the first waw in verse 26, which is also the eighth waw in verses 24–26.

To the artist, the eight waws symbolize infinity because the mathematical symbol of infinity (∞) looks like the number 8 placed horizontally. Infinity implies the divine. The photograph that is part of the sculpture shows the symbol.[11] Symbolically and numerically, then, the eighth waw, in verse 26, suggests the presence of divine energy coming down on “his wife” and giving her the impulse to look.

Levy-Aldema’s interpretation absorbs the reading of Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer, composed in Italy after 830 C.E. This interpretation explains that Lot’s wife vanishes because she sees the divine presence at the moment of looking back (Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer 25):

עִדִּית אִשְׁתּוֹ שֶׁל לוֹט נִכְמְרוּ רַחֲמֶיהָ עַל בְּנוֹתֶיהָ הַנְשׂוּאוֹת בִּסְדוֹם, וְהִבִּיטָה אַחֲרֶיהָ לִרְאוֹת אִם הָיוּ הוֹלְכוֹת אַחֲרֶיהָ אִם לָאו. וְרָאֲתָה אַחֲרֶיהָ הַשְּׁכִינָה, וְנַעֲשִׂית נְצִיב מֶלַח...

Idit, the wife of Lot, had compassion for her married daughters left in Sodom, and she looked behind her to see if they were following after her or not, and [instead] she saw the Shekhinah (Divine Presence), and became a pillar of salt…

Also Midrash Aggadah warns in Gen. 19:17 that nobody should look because the Shekhinah or God is in Sodom.[12] In other words, some rabbinic commentators affirm the notion of God’s presence in Sodom during the destruction. Levy-Aldema expands this idea to include verse 26. Standing firmly in his religious-intellectual tradition, the artist sees in the first waw of this verse the divine power that is needed for the wife to look. As she sees God, her transformation begins.

The Details of the Sculpture

The sculpture consists of seven round Plexiglas discs (six with mirrors and one without a mirror), a Plexiglas platform, an iron disc, a wheel of a fitness bike, a car jack, Ammonite fossil, scoria volcanic rock, a wooden box, a metal axe, acrylic color, six bolts, a rusty base with a silver cover coming from a table lamp, two blue beads, and a photograph.

Allusions to the Divine Presence

The top of the sculpture features seven Plexiglas discs arranged to resemble two satellite dishes, as if scanning the (infinite) skies for contact. The six discs on the right include mirrors to signify the tetragrammaton appearing six times prior to verse 26.[13] The single disc on the left symbolizes the implicit presence of God in the waw of verse 26. In addition, the sculpture’s photograph contains the abstract sign for infinity (i.e., God). The round hole of the Plexiglas platform represents God as a space that is there and not there at the same time. The divine presence is palpable, giving the impulse to Lot’s wife to act: “And she looks.”

|

|

Symbols of Divine Power

The mentioning of the tetragrammaton six times (Genesis 19:13 [twice], 14, 16, 24 [twice]) is also symbolized by six bolts that hold the entire Plexiglas platform together. In their immediate vicinity the bolts surround the piping that holds the discs up in the air and in place. The piping is screwed to a car jack underneath the Plexiglas platform. Intense forces hold the artwork upright. The piping is shaped in the form of a proto-Sinaitic waw (Y), indicating that God is indeed in the waw. The moment of the first waw in verse 26 takes place in the realm of God.

In the Hebrew, the verb, “look” (נ.ב.ט in the hiphʿil), forms a single word with waw, “and”: wa-tabbet. Accordingly, all the materials of the sculpture connect with each other. Six bolts hold the entire structure together. Everything hinges on the six bolts as they stabilize the Plexiglas platform. Without them, the piece would collapse. The six bolts symbolize the divine connections permeating the moment of “his” wife’s transformation, as God also annihilates the cities, the earth, the people, and all vegetation (19:25).

In the Hebrew, the verb, “look” (נ.ב.ט in the hiphʿil), forms a single word with waw, “and”: wa-tabbet. Accordingly, all the materials of the sculpture connect with each other. Six bolts hold the entire structure together. Everything hinges on the six bolts as they stabilize the Plexiglas platform. Without them, the piece would collapse. The six bolts symbolize the divine connections permeating the moment of “his” wife’s transformation, as God also annihilates the cities, the earth, the people, and all vegetation (19:25).

The waws of verses 24–25 (two waws in verse 24; four waws in verse 25) connect the four different ways of divine power: the destruction by brimstone and fire, the cutting down of the cities, the upside-down turning of the land, and the elimination of all vegetation. As God’s power resides in the waws of verses 24–25, the first waw of verse 26 is yet another indication of God’s implicit power.

The artist represents God’s methods of destruction in four items placed on the platform. They are:

| (1) a volcanic rock embodying brimstone and fire (v. 24; gaphrit wa-ʾesh meʾet YHWH min-hashamayim); | (2) an axe denoting the cutting down of the cities (v. 25; wayyahafokh et-heʿarim); |

|

|

| (3) a fossil symbolizing the land (v. 25; we-ʾet kol-hakkikkar); and | (4) a wooden box (in the pic above) signifying the vegetation, such as trees and bushes, on the earth (v. 25; we-tzemach haʾadama). |

|

|

Set in the Heavens

The location of the items on the platform, which divides the below from the above, indicates that the moment of transforming the wife into a salt pillar includes enormous violence. After all, a human being becomes a mineral in that transformative moment.

In the artistic interpretation, this moment begins in the realm of God, in the heavens (19:24: מִן־הַשָּׁמָיִם). God gives the wife the impulse, energy, or drive to look, and so begins her transformation into a pillar of salt. The transformation requires her death.

Levy-Aldema communicates the realm of God with a blue stand on which the entire platform rests. The balance of the artwork is fragile, as the blue stand is not placed firmly on the ground. The events take place in the heavens so the platform seems to float in the air. Everything that is connected to the platform appears to hang down or rise up from the above or the below of the platform. The whole artwork looks uneven, wobbly, and unstable, as if the various elements and even the entire platform hovered in the blue sky, in the heavens.

Levy-Aldema communicates the realm of God with a blue stand on which the entire platform rests. The balance of the artwork is fragile, as the blue stand is not placed firmly on the ground. The events take place in the heavens so the platform seems to float in the air. Everything that is connected to the platform appears to hang down or rise up from the above or the below of the platform. The whole artwork looks uneven, wobbly, and unstable, as if the various elements and even the entire platform hovered in the blue sky, in the heavens.

Divine Impulse Makes “His Wife” Look Back

The Plexiglas platform also features two blue nails in a silver face. They symbolize the eyes of “his wife,” as she looks at God. According to the artist’s interpretation, the eighth waw that is part of the Hebrew wa-tabbet, “and she looked,” implies the presence of divine energy. Coming down to the wife, God gives her the urge to look and look she does. Her eyes are popping out of her face.

The Plexiglas platform also features two blue nails in a silver face. They symbolize the eyes of “his wife,” as she looks at God. According to the artist’s interpretation, the eighth waw that is part of the Hebrew wa-tabbet, “and she looked,” implies the presence of divine energy. Coming down to the wife, God gives her the urge to look and look she does. Her eyes are popping out of her face.

The artwork is grounded in the theological conviction that the wife is able to look “back,” or more literally “from behind him [her husband]” (meʾacharaw),[14] because a larger-than-life force causes her to look. This force comes from the heavens, from God, giving her the impetus to abandon her life and to accept death.

The sculpture thus raises rarely asked questions: What makes “his wife” decide to look? Should we consider her looking as a sign of her weakness, for which she is punished by becoming a salt pillar?[15] Is her looking accidental, as she feels pity for the people dying in Sodom, destroyed by brimstone and fire sent by God (19:24)? Does the divine impulse trigger her to look at God’s destructive power and accept her death at this moment? The sculpture suggests that the impetus to look comes indeed from God.

Looking as an Act of Resistance

The moment leading up to the death of Lot’s wife is critical for understanding Levy-Aldema’s first sculpture on verse 26. This artwork on the letter waw emphasizes the divine involvement in the wife’s decision to look and see God at work, even accepting death for doing so. She experiences what Moses learns only later in Exod. 33:20, לֹא תוּכַל לִרְאֹת אֶת פָּנָי כִּי לֹא יִרְאַנִי הָאָדָם וָחָי “You cannot see my face; for no one shall see me and live.”

Yet the wife does not die in vain. She turns into a pillar of salt, into a monument for all to see until today. The question is for what cause or issue does she become a monument? In Levy-Aldema’s sculptural interpretation, she is a monument for women, wives, and mothers who refuse to be complicit with their husbands’ sexual violence toward their children, daughters or sons.

Note that just the night before, Lot invited sexual violence against his daughters when he offered them to the male Sodomites וַעֲשׂוּ לָהֶן כַּטּוֹב בְּעֵינֵיכֶם “to do with as you please” (Gen 19:8). Later in the same story, we hear of the troubling incestuous rape between Lot and his daughters in a cave where they are hiding, believing that they are the only human beings left in the world.

While the biblical text speaks about the daughters getting their father drunk and raping him (19:30–38), feminist interpreters, reading against the grain, emphasize that, according to social-science research, fathers rape children, not the other way around.[16] Accordingly, the story of Lot and his daughters in the cave needs to be read as an androcentric literary fantasy that presents the daughters as the active party of the incestuous rape when in reality such an act is always done by a father and not the children.

In such a situation, the mother generally knows what is happening, and must choose what her response will be. In many cases, mothers do not or cannot save the child from a father’s attack. A feminist reading, reclaiming the figure of Lot’s wife, sees in her a woman who knows about her husband’s sexually violent desires against their children, and refuses to be complicit with him. As she is powerless to control her husband’s behavior, she looks back, sees God, dies, and becomes a pillar of salt. In this way, she turns into a monument for any wife resisting an abusive husband.

Levy-Aldema’s sculptures—all seven of them—remind viewers that extraterrestrial forces—God—induce the extraordinary transformation of Lot’s wife. She could not have done it alone. When viewers look at the seven artworks, they are invited to recognize that Ms. Lot’s final words might have been: “I prefer death to being with my criminal husband any longer.”

The dialog with Levy-Aldema’s sculpture on the first waw of Gen. 19:26, then, leads to an unexpected meaning. Emphasizing the process of the woman’s miraculous transformation, viewers are invited to reconsider with whom and for what purpose they read this biblical verse. Do they read with the wife, recognizing what is involved in her transformation? Do they see her willingness to die as an act of solidarity with her daughters, as she leaves behind her life with her husband and the world?

She cannot protect her daughters from the event in the cave, but she also refuses to become part of it. The seven sculptures teach that this wife decides not to remain with her husband escaping to Zoar and later to the cave. With the support of God, she becomes a pillar of salt instead, a monument of a wife resisting her sexually violent husband.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

October 18, 2021

|

Last Updated

December 22, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Susanne Scholz is Professor of Old Testament at Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University (SMU) in Dallas, Texas. She holds a Ph.D. and S.T.M. from Union Theological Seminary in New York City and the equivalent M.Div. from the University of Heidelberg, Germany. She also studied at the University of Mainz, Germany, and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Israel. Scholz is the editor of many books, and is the author of The Bible as Political Artifact: On the Feminist Study of the Hebrew Bible (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2017), Introducing the Women’s Hebrew Bible: Feminism, Gender Justice, and the Study of the Old Testament (2nd rev. & exp. edn; T&T Clark Bloomsbury, 2017), Sacred Witness: Rape in the Hebrew Bible (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010).

Essays on Related Topics: