Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Shabbat Is Core to Jewish Identity—Even for the Secular

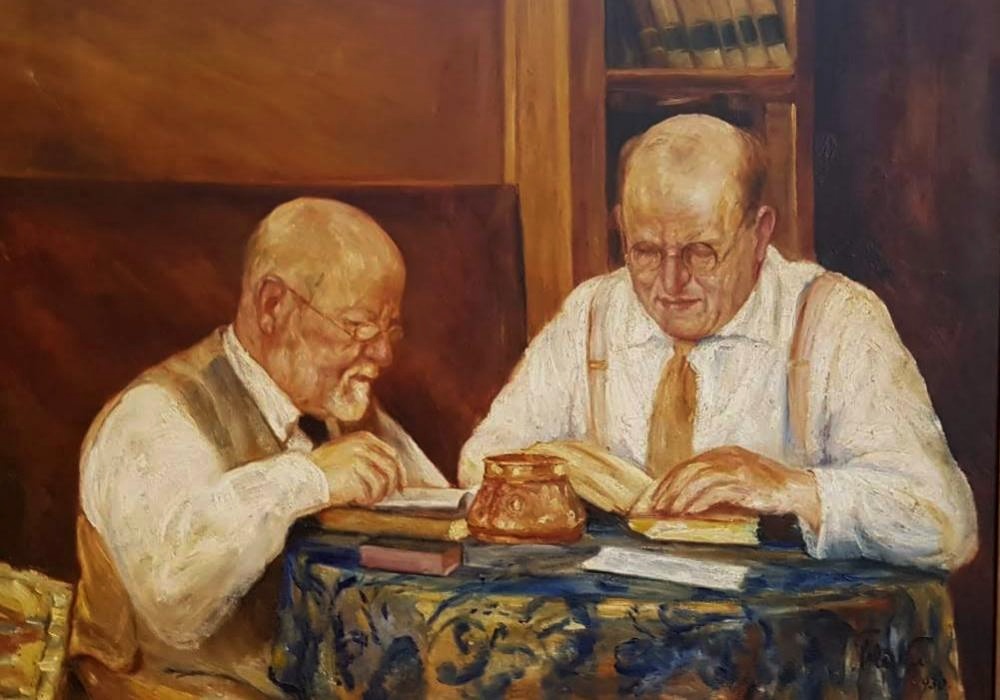

Hayyim Bialik (R) and co-editor Y. H. Ravnitzky work on their Sefer Ha-Aggadah, oil painting by Chaim Lipschitz, early 20th century. Wikimedia

“More than the people of Israel kept Shabbat, Shabbat kept them,” יותר משישראל שמרו את השבת שמרה השבת אותם. These famous remarks about the historical importance and safeguarding powers of Shabbat were published by Ahad Haʿam (Asher Ginsberg, 1856–1927), chief architect of cultural Zionism, in his June 1898 essay ילקוט קטן (Yalkut Katan “Small Collection”) in the journal Hashiloaḥ,[1] less than a year after the first Zionist Congress in Basel:

אין צורך להיות ציוני או מדקדק במצוות בשביל להכיר ערך השבת—אמר באותו מעמד אחד מגדולי הערה, והדין עמו. מי שמרגיש בלבו קשר אמתי עם חיי האומה בכל הדורות, הוא לא יוכל בשום אופן—אפילו אם אינו מודה לא בעולם הבא ולא במדינת היהודים—לצייר לו מצואות עם ישראל בלי "שבת מלכתא".

One need not be a Zionist or punctilious in the observance of mitzvot in order to recognize the value of Shabbat – said one of the leaders of the movement [in Berlin], and he is correct. Whoever feels in his heart a true connection with the life of the nation over the generations will not be able to imagine under any circumstances—even if he denies the World to Come or the idea of a Jewish State—a reality in which the People of Israel are without the “Sabbath Queen.”

אפשר לאמור בלי שום הפרזה, כי יותר משישראל שמרו את השבת שמרה השבת אותם, ולולא היא שהחזירה להם "נשמתם" וחדשה את חיי רוחם בכל שבוע, היו התלאות של "ימי המעשה" מושכות אותם יותר ויותר כלפי מטה, עד שהיו יורדים לבסוף לדיוטא התחתונה של "חמריות" ושפלות מוסרות ושכלית.

One can say without exaggerating that more than the people of Israel kept Shabbat, Shabbat kept them. Without her returning their souls each week, the tribulations of the workweek (lit., the days of doing) would pull them ever lower, until they would reach the lowest stratum of materialism, and moral and intellectual degradation.

ועל כן בוודאי אין צורך להיות ציוני בשביל להרגיש כל הדר הקדושה ההיסטורית, החופפת על "מתנה טובה" זו. ולהתקומם בכל עוז נגד כל הנוגע בה.

For this reason, one certainly does not need to be Zionist in order to recognize the glory and historical holiness that envelops this “good gift,”[2] and to rise up with strength against anything that threatens it.[3]

Ahad Ha’am’s views about the crucial nature of Shabbat for the Jewish people, in general, and the Zionist project, in particular, insisting that a Jewish national home in Palestine must serve first and foremost as a spiritual and cultural center rather than merely a political refuge, were carried forward after his death by his acolyte and younger colleague Hayyim Nahman Bialik and his followers in the form of a cultural organization called ʿOneg Shabbat (עונג שבת “Enjoyment of Shabbat”), a rabbinic term referencing the requirement for people to make their Shabbat enjoyable with good food, rest, and other activities.[4]

Bialik’s Secular Beit Midrash for the Oneg Shabbat Movement

In 1894, Bialik wrote a poem titled, על סף בית המדרש (ʿAl Saf beit hamidrash, “On the Threshold of the Study House”), in which he committed to rebuilding the culture of the Beit Midrash, what he calls the Tent of Shem, in a new form:

לֹא תָמוּט, אֹהֶל שֵׁם! עוֹד אֶבְנְךָ וְנִבְנֵיתָ[5]

You shall not fall, O tent of Shem! I will yet rebuild you, and you shall be rebuilt;

מֵעֲרֵמוֹת עֲפָרְךָ אֲחַיֶּה הַכְּתָלִים;

From the heaps of your dust I will revive the walls.

Bialik’s early vision in that poem came to life when, on May 10, 1929, a new building in Tel Aviv, called “Ohel Shem” was dedicated to house the Oneg Shabbat movement, a social club and organization, which was committed to fostering a secular Hebrew life and culture based on the eternal values of the Jewish people:

Dedicate Hebrew Culture Club in Tel Aviv (Jewish Telegraphic Agency).

Tel Aviv, May 11—A building to house a social club and a people’s university to be known as the Ohel Shem, tent of Shem, was dedicated here yesterday in the presence of many Tel Avivians.

The site for the structure was provided by the Jewish National Fund, while the building expense, amounting to £5,000, was donated by an American Jew, Samuel Bloom, formerly of Philadelphia and now a manufacturer of artificial teeth in Tel Aviv.

The plan was originally conceived to provide permanent quarters for the Oneg Sabbath, a social club of writers and scholars which sprung up recently in Tel Aviv and meets every Saturday afternoon, following an old Jewish tradition to “enjoy the Sabbath,” by an interchange of views and opinions in a social atmosphere.

The club originally met in the home of Chaim Nachman Bialik, Hebrew poet. Later it became the custom to change the meeting place every Saturday. Mr. Bloom then offered the erection of a permanent headquarters for the club, which is expected to be utilized for educational and social purposes by the residents of Tel Aviv. A board of trustees, headed by Chaim Nachman Bialik, has been formed.

Speakers at the exercises were Mr. Bialik, Mr. Bloom, Mayor Dizengoff, and others.[6]

The purpose of the Oneg Shabbat movement was to create a cultural center, scholarly and literary, dedicated to the dissemination of a new Torah of Judaism steeped in the spirit of the original culture and traditions of Israel.

The two names, Ohel Shem and Oneg Shabbat, reflect a dual interest in Western secular and Jewish culture, in universalism and particularism combined. Oneg Shabbat reflects the devotion of Bialik and his followers to Shabbat as a symbol of Judaism’s unique cultural gifts, while Ohel Shem derives from Noah’s blessing of his sons Shem and Japhet, which the rabbis understand to represent the connection between Jews (=Shem) and Gentiles (=Japhet). Specifically, the Talmud claims that Genesis 9:27 is the prooftext for Rabban Shimon ben Gamaliel’s view that Torah scrolls may be written in Greek:

בבלי מגילה ט: ואמר ר' אבהו אמר ר' יוחנן: "מאי טעמא דרבן שמעון בן גמליאל? דכתיב (בראשית ט:כז) ' יַפְתְּ אֱלֹהִים לְיֶפֶת וְיִשְׁכֹּן בְּאׇהֳלֵי שֵׁם'—דבריו של יפת יהיו באהלי שם."[7]

b. Megillah 9b Rabbi Abahu said in the name of Rabbi Yohanan: “What is Rabban Shimon ben Gamaliel’s reasoning? For it says (Gen 9:27): ‘May God enlarge Japheth, and let him dwell in the tents of Shem’—the words (=language) of Japheth in the tents of Shem.”

This combination of imagery, Oneg Shabbat in the Tents of Shem building, highlights how this group aimed to straddle the fence of universalist relevance and sophistication with Jewish authenticity.

Shabbat Ritual for the Secular

Against the grain of some Zionist secularists, eager to jettison all Jewish practice, Bialik sought out ways to harness the temporal power of Shabbat and place it at the center of cultural life in Eretz Yisrael. His devotion to the centrality of Shabbat was articulated in his career in his famous essay, “Halakhah and Aggadah” (1917):

לבני־ישראל יש יצירה נהדרה שלו – יום קדוש ונעלה, ״שבת המלכה.״ בדמיון העם היתה לנפש חיה בעלת גוף ודמות הגוף, כלילת זוהר ויופי. היא השבת שהכניסה הקדוש ברוך הוא לעולמו בגמר מעשה בראשית...

The Children of Israel have their own glorious creation—a lofty, holy day, “The Sabbath Queen.” In the imagination of the nation, she has become living soul with a body and image, of consummate radiance and beauty. She is the Shabbat that God brought into God’s world at the the end of the Creation story...

היא שהיתה חמדה טובה להקדוש ברוך הוא בבית גנזיו ולא מצא לה בן־זוג נאה אלא ישראל... בכניסתה לעיר – הכל הופכים פניהם כלפי הפתח ומקבלים פניה בברכה: ״בואי כלה, בואי כלה, שבת המלכה!״ וחסידים יוצאים לקבלת פניה אל השדה.

It was she who was a goodly delight in God’s treasure house, for whom God found no fine partner other than Israel… When she enters the city—all turn their faces toward the door and greet her with a blessing: “Come, O bride! Come, O bride!—The Sabbath Queen!” and the pious go out to receive her in the fields.

These convictions about the centrality of Shabbat were once again reflected in his remarks at the dedication to the Ohel Shem building, which he later published.[8] He begins by noting that the Zionist goal is to establish a unique Jewish culture in the land:

ברצוני לברר את תוכן הרעיון של "עונג שבת". אנו באים לא[רץ] י[שראל] לחדש את חיינו; אנו רוצים ליצור לנו כאן חיים עצמיים, שיש להם קלסתר פנים משלהם ואופי מיוחד, ומייסדי "ענג שבת" חשבו, כי לשם יצירת צורות חיים מקוריות ואמתיות בעלות פרצוף ופנים לאומיים, הכרח להם לקחת את החומר ליצירותיהם מאבני היסוד של צורות החיים הקדמוניות.

I’d like to clarify the idea behind “Oneg Shabbat.” We have come to the Land of Israel to renew our lives; here we want to create for ourselves autonomous lives, with their own distinctive features and personality, and the founders of “Oneg Shabbat” thought, that for the purpose of creating original and true ways of life that have a national feature and character, it would necessary for them to take the material for their creative works from the foundation stones of our ancient ways of life.

Bialik asserts that part of the modern Jewish autonomy that he identifies with modern Zionism is a dedication to Shabbat, which he considers a cornerstone of Judaism:

ואם צריכים לחצוב "מן השתין" הרי יש לקחת את "אבן השתיה", את היסוד היותר חזק, ולא מצאו צורה יותר עליונה ויותר עמוקה להתחיל לטוות ממנה את צורות החיים המקוריות מיצירת השבת, שהיא, כידוע, קדמה למתן תורה ועוד במצרים שמרו בני ישראל את השבת. ואמנם השבת היא אבן השתיה של כל היהדות, ולא לחנם היא נקראת "אות ברית" בין אלהים ובין בני ישראל;

And if one needs to hew “from the very foundations,”[9] one needs to draw from “the foundation stone,”[10] the strongest base, and they found no loftier and no deeper form from which to weave these original forms of life than the creation of the Shabbat, which, as is well known, preceded the giving of the Torah,[11] with the Israelites observing Shabbat even while still in Egypt.[12] Indeed, Shabbat is the cornerstone of all of Judaism, and it is not for naught that she [the Sabbath] is called the “sign of the covenant”[13] between God and the Israelites.

Shabbat really is unusually dominant in the Torah, where it appears in 14 different passages.[14] In terms of repetition, Shabbat is eclipsed only by the prohibition against oppressing the stranger (ger), which, Rabbi Eliezer the Great notes, is warned against 36 or perhaps 46 times (b. Bava Metzia 59b).[15]

Bialik explains that Shabbat is a key element of the Jewish core because of the way it shows Jewish mastery over rather than subservience to time:

בשבת מקופלים כמה רעיונות לאומיים וסוציאליים, ואם ב"עשרת הדברות" מקופלת כל התורה... ...לעם ישראל יש שליטה על הזמן. היהודים קובעים את זמן חגיהם ומגבוה מסכימים להם – "השבת מסורה בידכם ואין אתם מסורים לשבת". [...] אם אנו חוזרים לא"י – עלינו לחזור עם השבת, זה הסמל שלנו המלא יופי וחן, שממנו נוכל לשאוב יופי לכל צורות החיים שלנו.

Shabbat encompasses several national and social ideas, and if the Ten Commandments encompasses all the Torah[16], then it may be that all the Ten Commandments are folded in and embodied in Shabbat… The nation of Israel exercises control over Time. The Jews establish the time of their holidays and receive assent from one high—“Shabbat is given over to your hands; you aren’t given over to the Shabbat.”[17] [… ] And if we’re returning to the Land of Israel—it is incumbent upon us to return with the Shabbat, it is our symbol of beauty and grace, from which we can draw beauty for all forms of our life.

Bialik ends by noting the centrality Shabbat has had in the past and should have now, followed by a blessing and then a midrashic play on the name Japhet, which has the same letters as the Hebrew word for beauty:

אנו יודעים מהו סגנון עליון ושאיפה לשכלול. שמאי הזקן – כל דבר נאה שנזדמן לו הניחהו בשביל שבת. השבת מקדשת את רגש היופי של כל האומה כולה. ...ואני מברך את עצמנו שנזכה להתענג בימי השבת ושיהיו לנו הרבה "אהלי-שם", שבהם תושכן גם מיפיפיותו של יפת.

We are familiar with exalted style and the aspiration toward perfection. Shammai the Elder—everything that came his way, he set it aside for Shabbat.[18] Shabbat sanctifies the aesthetic feelings of the entire nation. […]And I bless that we should all merit to enjoy our Shabbat days and see many “Tents of Shem,” in which the cultural beauty of “Yefet” dwells, as well.

Halakhically, What Takes Place at Ohel Shem on Shabbat?

Bialik’s halakhic rule with regard to Ohel Shem was to avoid any activity in the building that would denigrate the tradition and holiness of Israel and Hebrew culture. Instead, Oneg Shabbat events in the building—lectures, study sessions, concerts, singalongs—would bring together the genres of Jewish study and culture and elevate Shabbat and Jewish culture for this new age.

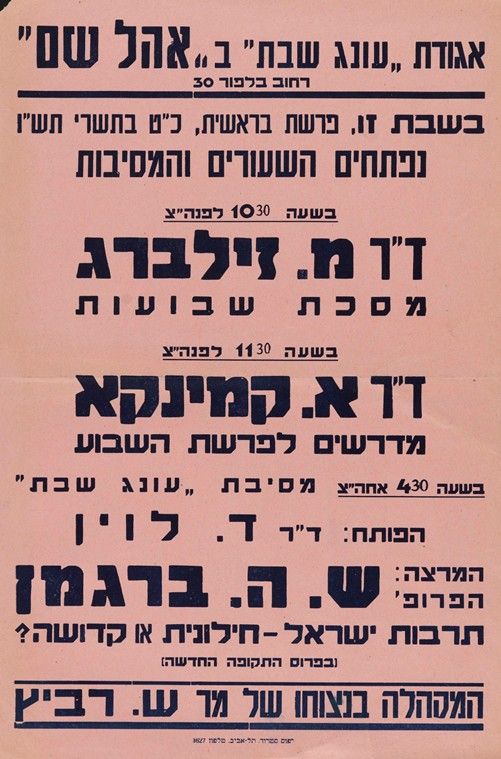

Note the range of topics advertised in this Oneg Shabbat poster from Parashat Bereshit, 1945:

The roster includes two morning lectures: Dr. Moshe Zilberg (1900–1975, a Yeshiva-trained lawyer and teacher and friend of Bialik’s) on Tractate Shevuot at 10:30am; Dr. Aharon (Armond) Kaminka (1866–1950, a prominent Russian-born rabbi, scholar, and Zionist activist) on midrashim related to the parasha at 11:30am. Then an afternoon Oneg Shabbat celebration (מסיבה) at 4:30pm, kicked off by Dr. David Levin (1880–1960, a Russian-born educator and activist on behalf of the Hebrew Revival), followed by a main lecture by Prof. Shmuel Hugo Bergmann, (1883–1975)[19] titled, “The Culture of Israel; Secular or Holy? [In the Unfolding of the New Era].” This also included a choir performance conducted by Mr. Shlomo Ravitz (1885–1980).

The Sabbath Queen: Bialik’s Poem

Bergmann’s interest in exploring and blurring the distinction between secular and profane in the context of “Oneg Shabbat” was anticipated by Bialik himself in his 1901 song “Shabbat Hamalkah” (שבת המלכה, “The Sabbath Queen”). Bialik wrote it as an updated version of Shalom Aleichem (שלום עליכם, “Peace Unto You,” Tzfat 16th-17th century, author unknown), the traditional song greeting the ministering angels, sung on Friday night at the Shabbat table before the meal:

שָׁלוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם מַלְאֲכֵי הַשָׁרֵת מַלְאֲכֵי עֶלְיוֹן

Peace unto you, ministering angels, angels of the most high

מִמֶלֶךְ מַלְכֵי הַמְלָכִים הַקָדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא...

From the King of kings, the Blessed Holy One…[20]

The song is based on a Talmudic passage that two angels accompany a person home from synagogue on Sabbath Eve, one good and one evil:

בבלי שבת קיט: [אוקספרד 366] תניא ר' יוסי בר יהודה אומר: שני מלאכי השרת מלוין לו לאדם בערב שבת מבית הכנסת לביתו אחד טוב ואחד רע.

b Shabbat 119b It was taught: Rabbi Yossi bar Yehuda says: Two ministering angels accompany a person on Shabbat evening from the synagogue to his home, one good and one evil.

וכשבא לביתו מוצא נר דולק ושלחנו ערוך ומטתו מוצעת מלאך טוב אומר: "יהי רצון שתהא שבת אחרת כך." ומלאך רע עונה "אמן" על כרחו. ואם לאו מלאך רע אומר: "יהי רצון שתהא שבת אחרת כך." ומלאך טוב עונה "אמן" על כרחו.

And when he reaches his home, and finds a lamp burning, and his table set, and his bed made, the good angel says: “May it be willed that it shall be like this for another Shabbat.” And the evil angel answers “amen” against his will. And if not, the evil angel says: “May it be willed that it shall be so for another Shabbat,” and the good angel answers “amen” against his will.

The song (Shalom Aleichem) reimagines the Talmud’s notion of accompanying angels but removes the evil angel. Instead, the person reciting the song greets and welcomes the angels, in the plural, beseeching them for blessing and then sending them on their way. Bialik’s poem “The Sabbath Queen” adopts a similar four-stanza structure and thematic tack, welcoming all malaʾakhim—a word that can mean both angels and human messengers—with a set table, festive clothes, song and prayer and three meals.

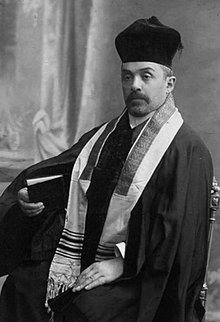

While he wrote the text of the song, Cantor Pinḥas Minkowsky of the Brodsky synagogue in Odessa composed the well-known melody. The piece became part of the repertoire of Sabbath songs sung in synagogues, Jewish homes, and later, Jewish camps.

Updating Shalom Aleichem for the Modern Jew

In many respects the song reads and sounds like an entirely traditional piyyut (liturgical poem). Comparing it to Shalom Aleichem, however, brings out its mix of traditionalism and secularism. The first stanza read (Hear Yehoram Gaon’s rendition of “Shabbat Ha-Malkah.”):

הַחַמָּה מֵרֹאשׁ הָאִילָנוֹת נִסְתַּלְּקָה –

בֹּאוּ וְנֵצֵא לִקְרַאת שַׁבָּת הַמַּלְכָּה.

הִנֵּה הִיא יוֹרֶדֶת הַקְּדוֹשָׁה, הַבְּרוּכָה,

וְעִמָּהּ מַלְאָכִים צְבָא שָׁלוֹם וּמְנוּחָה.

The sun on the tree-tops no longer is seen,

Come, gather to welcome the Sabbath, our Queen.

Behold her descending, the holy, the blessed.

With angels a cohort of peace and of rest.[21]

בֹּאִי, בֹּאִי, הַמַּלְכָּה!

בֹּאִי, בֹּאִי, הַמַּלְכָּה! –

שָׁלוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם, מַלְאֲכֵי הַשָּׁלוֹם!

Come, come, the Sabbath Queen!

Come, come, the Sabbath Queen

Peace also to you, angels of peace!

The first line makes use of the verb nistalkah (disappeared and removed herself), which is repeatedly used in rabbinic literature to connote the departure of the Divine Spirit. For example, the Talmud has the Divine Spirit depart from Israel after the end of the age of prophecy, though is replaced by a Bat Kol, a divine echo or voice:

בבלי סנהדרין יא. תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: מִשֶּׁמֵּתוּ נְבִיאִים הָאַחֲרוֹנִים חַגַּי זְכַרְיָה וּמַלְאָכִי, נִסְתַּלְּקָה רוּחַ הַקּוֹדֶשׁ מִיִּשְׂרָאֵל. וְאַף עַל פִּי כֵן הָיוּ מִשְׁתַּמְּשִׁין בְּבַת קוֹל.

b. Sanhedrin 11a The Sages taught: After the last of the prophets, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, died, the Divine Spirit of prophetic revelation departed from the Jewish people. But nevertheless, they were still utilizing a Divine Voice.[22]

Similarly, according to Shemot Rabbah, the Divine Presence is seen departing from the heavens after the destruction of the Temple:

שמות רבה ב:ב וּמשֶׁה הָיָה רֹעֶה, הֲדָא הוּא דִכְתִיב (חבקוק ב:כ): "וַה' בְּהֵיכַל קָדְשׁוֹ". אָמַר רַבִּי שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר נַחְמָן: עַד שֶׁלֹא חָרַב בֵּית הַמִּקְדָּשׁ הָיְתָה שְׁכִינָה שׁוֹרָה בְּתוֹכוֹ, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר (תהלים יא:ד): "ה' בְּהֵיכַל קָדְשׁוֹ", וּמִשֶּׁחָרַב בֵּית הַמִּקְדָּשׁ נִסְתַּלְּקָה הַשְּׁכִינָה לַשָּׁמַיִם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר (תהלים קג:יט) "ה' בַּשָּׁמַיִם הֵכִין כִּסְאוֹ".

Exod Rab 2:2 “Moses was herding” – that is what is written: “God was in His sacred Sanctuary” (Habakkuk 2:20). Rabbi Shmuel bar Naḥman said: Until the Temple was destroyed, the Divine Presence rested in it, as it is stated (Psalms 11:4): “God was in His sacred Sanctuary.” When the Temple was destroyed, the Divine Presence departed to the heavens, as it is stated (Psalms 103:19): “The Lord established His throne in the heavens.”

Bialik’s use of the rabbinic “nistalkah” to connote the disappearance of the sun and hence, the arrival of Shabbat, subtly points to his modern Jewish sensibility: the need for old notions to give way to new cultural and spiritual forms.

Bialik’s choice of the clause, הִנֵּה הִיא יוֹרֶדֶת (“Behold she descends”), which contrasts with the traditional phrasing, Kenissat haShabbat, “the entrance of the Sabbath,” pictures Shabbat as coming down, as if from heaven to earth, to join the people.

The song continues with:

קִבַּלְנוּ פְּנֵי שַׁבָּת בִּרְנָנָה וּתְפִלָּה,

הַבַּיְתָה נָשׁוּבָה, בְּלֵב מָלֵא גִילָה.

שָׁם עָרוּךְ הַשֻּׁלְחָן, הַנֵּרוֹת יָאִירוּ,

כָּל-פִּנּוֹת הַבַּיִת יִזְרָחוּ, יַזְהִירוּ.

We’ve welcomed the Sabbath with song and with prayer;

And home we return, our heart's gladness to share.

The table is set and the candles are lit,

The tiniest corner for Sabbath made fit.

שַׁבָּת שָׁלוֹם וּמְבֹרָךְ!

שַׁבָּת שָׁלוֹם וּמְבֹרָךְ!

בֹּאֲכֶם לְשָׁלוֹם, מַלְאֲכֵי הַשָּׁלוֹם!

Blessed Sabbath of peace

Blessed Sabbath of peace

Peace also to you, angels of peace!

שְׁבִי, זַכָּה, עִמָּנוּ וּבְזִיוֵךְ נָא אוֹרִי

לַיְלָה וָיוֹם, אַחַר תַּעֲבֹרִי.

וַאֲנַחְנוּ נְכַבְּדֵךְ בְּבִגְדֵי חֲמוּדוֹת,

בִּזְמִירוֹת וּתְפִלּוֹת וּבְשָׁלֹש סְעֻדּוֹת.

Sit with us pure one, and in your splendor illuminate

Night and day, and then go on your way.[23]

We’ll honor your with festive clothes,

With song and prayer and three meals.

וּבִמְנוּחָה שְׁלֵמָה

וּבִמְנוּחָה נָעֵמָה –

בָּרְכוּנוּ לְשָׁלוֹם, מַלְאֲכֵי הַשָּׁלוֹם!

With complete rest

With pleasant rest –

Bless us for peace, angels of peace!

Bialik’s attentiveness to the preparations for Shabbat brings to mind the Talmudic story about Shammai the Elder and how he would prepare all week long for Shabbat, which Bialik would later cite in his speech on the dedication of Ohel Shem, quoted above:

בבלי ביצה טז. [וטיקן 109ב] תניא: אמרו עליו על שמאי הזקן שכל ימיו היה אוכל לכבוד שבת. כאי זה צד? מצא בהמה נאה אומר: "זו לכבוד שבת." למחר מצא בהמה נאה הימינה, היה אוכל אותה ראשונה ומניח השנייה, ונמצא כל ימיו אוכל לכבוד שבת.

b. Beitzah 16a It was taught: They said about Shammai the Elder that all his days he would eat in honor of Shabbat. How is that? If he found a choice animal, he would say: “This is for Shabbat.” If he subsequently found another an animal choicer than it, he would eat the first and set aside the second. In this way, he would eat in honor of Shabbat all his days.

Finally, as if anticipating doubt about the faithfulness of this new, modern Shabbat community, Bialik turns in the last stanza to the Sabbath Queen and offers his reassurance that the community will be ready and waiting for her each week, to do it all again.

הַחַמָּה מֵרֹאשׁ הָאִילָנוֹת נִסְתַּלְּקָה –

בֹּאוּ וּנְלַוֶּה אֶת-שַׁבָּת הַמַּלְכָּה.

צֵאתֵךְ לְשָׁלוֹם, הַקְּדוֹשָׁה, הַזַּכָּה –

דְּעִי, שֵׁשֶׁת יָמִים אֶל שׁוּבֵךְ נְחַכֶּה.

The sun on the tree-tops no longer is seen,

Come, gather to accompany the Sabbath, our Queen.

Go in Peace, one holy and pure

Know, for six days we await your return.

כֵּן לַשַּׁבָּת הַבָּאָה!

כֵּן לַשַּׁבָּת הַבָּאָה!

צֵאתְכֶם לְשָׁלוֹם, מַלְאֲכֵי הַשָּׁלוֹם!

Until next Shabbat!

Until next Shabbat!

Go in peace, angels of peace!

Bialik’s conviction, as articulated on his Ohel Shem speech, that the people of Israel control time and perforce, make Shabbat what it is meant to be, is underscored, throughout his poem, by the use of the first-person plural:

- קִבַּלְנוּ “we greeted”;

- נָשׁוּבָה “We shall return”;

- וַאֲנַחְנוּ נְכַבְּדֵךְ “and we shall honor you”;

- בֹּאוּ וּנְלַוֶּה “Let’s accompany.”

It is up to the people, says Bialik, to revitalize Shabbat for the modern age, adapting its traditional forms into something new for our times. Conspicuously absent from Bialik’s poem, then, and from Bialik’s later speech on the dedication of “Ohel Shem,” is any mention of God, מֶלֶךְ מַלְכֵי הַמְלָכִים הַקָדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא “the King of Kings the Holy Blessed One,”[24] who caps each of the four stanzas of the “Shalom Aleichem” piyyut, even as the song insists on including the language of holiness and blessing, and conspicuously references the "Lekha Dodi" prayer.

Secular Shabbat Then and Now

Bialik’s vision of claiming an emotional and serious connection to Shabbat even in secular circles continues to inspire the contemporary Israeli movement of Hitḥadshut Yehudit “Jewish Renewal” – its own form of Jewish Secular Religious Renaissance, and undermines the longstanding assumed binary between secular and religious Judaism in Israel.[25]

At Israeli Liberal synagogues such as Beit Tefilah Yisraeli and Beit Daniel in Tel Aviv, and at Kabbalat Shabbat services at various liberal congregations throughout Israel, Bialik’s project—to make Hebrew once again a spoken, sung, emotionally charged language—is foundational. Their siddurim and services privilege modern Hebrew alongside biblical and rabbinic Hebrew and integrate poetry and song as legitimate forms of prayer.

Bialik’s essays on Shabbat and poems like “Shabbat Hamalkah” continue to serve as a spiritual basis for music, singing, and aesthetic experience as religious experience, in which Japhet resides within the tent of Shem.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 2, 2026

|

Last Updated

February 2, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi Wendy Zierler is the Sigmund Falk Professor of Modern Jewish Literature and Feminist Studies at HUC-JIR. She received her Ph.D. and M.A. from Princeton University, her MFA in Fiction Writing from Sarah Lawrence College, her B.A. from Stern College (YU), and her rabbinic ordination from Yeshivat Maharat. She is the author of And Rachel Stole the Idols: The Emergence of Hebrew Women’s Writing, and co-editor of Prooftexts: A Journal of Jewish Literary History. Most recently she co-edited the book These Truths We Hold: Judaism in an Age of Truthiness.

Essays on Related Topics: