Edit article

Edit articleSeries

What Sukkot Meant to Jews and Gentiles in Greco-Roman Antiquity

Sukkot, Hoshana Rabbah 2013 at the Hurva Synagogue, Jerusalem. Wikimedia

Today, for many non-observant Jews, Sukkot is a vaguely known holiday with palm fronds and perhaps an annual synagogue sukkah-hop for the kids.[1] In contrast, Sukkot was a central holiday for Jews in antiquity. The very fact that Sukkot could simply be called “the festival” (החג) is an indicator of its prominence.[2]

In Greco-Roman antiquity, if Jews had been surveyed about which of the Jewish festivals was the most important to them (besides the weekly Shabbat), Sukkot, the feast of tabernacles, might very well have emerged as the winner. A survey of non-Jews about Jewish festivals would probably have arrived at the same answer.

The Place of Sukkot in Jewish Antiquity

The importance of Sukkot in Greco-Roman antiquity can be inferred from a number of sources. The book of Jubilees (2nd century B.C.E.), which predates many Torah laws to a time preceding the Sinaitic revelation, describes Abraham celebrating the feast of booths (16.20-31):[3]

16:29 Therefore it is ordained in the heavenly tablets concerning Israel that they will be observers of the feast of booths seven days with joy in the seventh month… 16:30 …and they should dwell in tents[4] and that they should place crowns on their heads[5] and so that they should take branches of leaves and willow from the stream. 16:31 And Abraham took branches of palm trees and fruit of good trees and each day of the days he used to go around the altar with branches. Seven times per day, in the morning, he was praising and giving thanks to his God for all things. (trans. Outside the Bible, 1:353).

In Jubilees, Abraham’s celebration of Sukkot avant la lettre follows the joyful event of Isaac’s birth. This fits with the general theme of Sukkot which is described in Jewish and pagan sources as a festival of joy,[6] filled with agricultural symbols of blossoming.

But Sukkot could also be understood as a time of earnest reflection: Philo of Alexandria, the great Jewish philosopher and theologian of the first half of the first century C.E., takes Sukkot as an occasion to think about justice as well as the ephemerality of peace and security. To Philo Sukkot is an ideal moment to consider difficult times:

And indeed it is well in wealth to remember your poverty, in distinction your insignificance, in high offices your position as a commoner, in peace your dangers in war….[7]

How fragile safety and peace can be, Philo himself witnessed when, in the year 38 C.E., an anti-Jewish riot broke out in Alexandria and the Jews huddled in their homes in fear. Referring to that year’s Sukkot, Philo wrote, when “it is the custom of the Jews to live in booths, none of the usual customs at this festival were carried out at all.”[8]

Epigraphic Evidence of Sukkot’s Importance

In addition to literary documents, epigraphic evidence also points to the significance of Sukkot in antiquity: The symbols of Sukkot carved in numerous funeral inscriptions. For example, a Latin inscription from the Jewish catacomb Vigna Randanini in Rome commemorating “Nepia Marosa who lived four years,” is decorated with the most important symbols of Jewish antiquity: the menora, the shofar, an oil (?) flask, and – from the symbolic world of Sukkot – an etrog and a lulav with open leaves. [9]

Plutarch on Jewish Rituals

The attitude of Gentiles of the Greco-Roman period to Sukkot is particularly striking. In his Table Talk, Plutarch, a philosopher and biographer from Chaeronea (Boeotia) in Greece, writing in Greek (1st to 2nd century CE), launches a dialogue in which the participants of a symposium debate Jewish rituals.

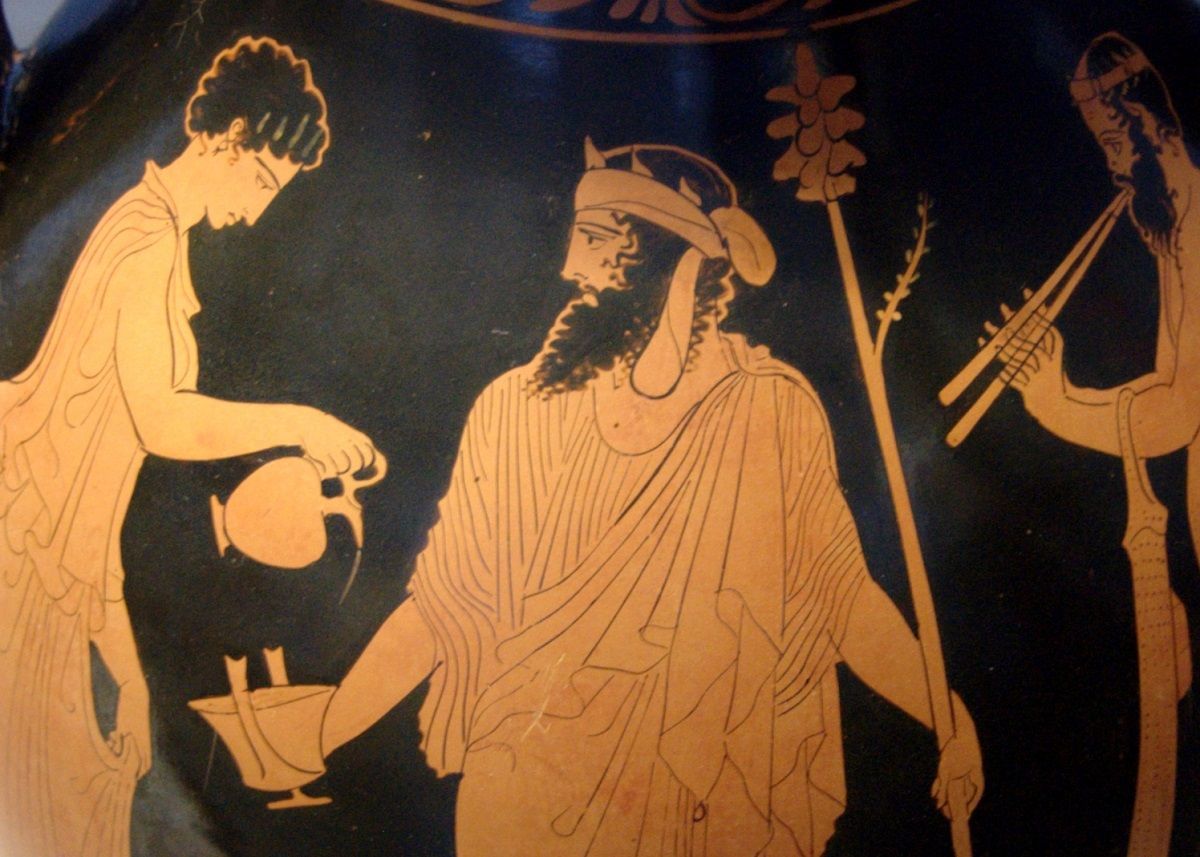

First they wonder whether the Jewish abstention from pork is the result of admiration or contempt of this animal.[10] And then they discuss the nature of this god of the Jews. In the context of the latter question, one of the participants of the symposium, the Athenian Moeragenes, refers to parallels between the Jewish feast of Booths and festivals in honor of Dionysus or Bacchus, the Greek and Latin names for the fertility god of the grape-harvest and wine making:

First of all, he said, the time and character of the greatest, most sacred holiday of the Jews clearly befit Dionysus. For when they celebrate their so-called Fast [see discussion below], at the height of the vintage, they set out tables of all sorts of fruit under tents and huts plaited for the most part of vines and ivy. They call the first of the days Booth.

A few days later they celebrate another festival, called openly, no longer through obscure hints, a festival of Bacchus. This festival of theirs is a sort of bearing of branches and of thyrsi [“rods”, see discussion below] in which they enter the temple carrying the thyrsi. What they do after entering we do not know, but it is probable that what they are doing is a Bacchic revelry, for in fact they use little trumpets to invoke their god as do the Argives at their Dionysia. Others of them advance playing harps; they themselves call them Levites, either from Lysios [“Releaser”, an epithet of Dionysus] or, better, from Evius [from the cry “euhoi” used in the cult of Dionysus].[11]

Moeragenes then adds another parallel between Jewish customs and Dionysus: The Sabbath can also be understood as a Bacchic festival, since among other things “when they celebrate the Sabbath they invite each other to drink and to enjoy wine.” Even “when something important interferes with this custom, they regularly take at least a sip of neat wine.”[12]

Parsing Plutarch’s Passage

The passage in Plutarch is difficult, and the transmission of the Greek is not always clear.[13]Some of what is reported about Jewish customs concurs with Jewish sources, while other observations seem to be the result of misunderstanding or confusion. Clearly, some aspects and names related to the Jewish rituals are replaced with terms from the pagan world (a phenomenon called Interpretatio Graeca).[14]

These seeming misunderstandings include:

A Fast Called Booths – By referring to the festival of Sukkot/Booths as a “so-called fast day” the author (or his source) is mixing up Sukkot with the preceding Yom Kippur.[15]

A Few Days Later – What does Plutarch mean by the festival that is celebrated “a few days later”? Shemini Azeret has been suggested, since, biblically speaking, it is the next festival.[16]Nevertheless, a more likely candidate may be Hoshana Rabbah, the seventh day of Sukkot with its seven circuits.

Such confusion notwithstanding (of which some may be the result of textual transmission), Plutarch’s presentation of Sukkot fits many aspects of the actual Jewish festival as it is described in ancient Jewish sources and as it continues to be celebrated up until today:

Booths – At the core of Sukkot are booths or huts which gave the festival its name. Plutarch’s description of a Sukkah has parallels in the discussion of the Mishnah (cf. m. Sukkah 1:4 on huts plaited of vines and ivy. Incidentally, the Mishnah uses the same word for ivy (קסוס) as Plutarch (κιττός, the Attic form of κισσός).

Trumpets – Mishnah Sukkah (4:5, 5:1) describes the blowing of trumpets as a prominent part of the Sukkot celebration.

Levites playing harps – Levites playing music are already known to us from the later books of the Bible, and Levites playing harps specifically on Sukkot is mentioned in the Mishnah as well (Sukkah 5:4).

Tacitus: The Jewish God is Not Like Dionysus

Plutarch is not the only ancient source connecting Sukkoth with Dionysiac rituals. The Roman historian Tacitus, a contemporary of Plutarch, also knows of the comparison between the Jewish God and Dionysus:

Since the Jews’ priests used to chant to the accompaniment of pipes and drums and to wear garlands of ivy, some have thought that they were devotees of Father Liber [Bacchus].[17]

Tacitus however, in his polemic against Judaism,[18] rejects any kind of correspondence between Jewish and Roman rituals (nequaquam congruentibus institutis: “the institutions have nothing in common at all”).

The Lulav and Dionysian Ritual

Plutarch and Tacitus, both writing after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E., in their remarks on Sukkot seem to refer to the Sukkot rituals as performed in the Jerusalem Temple. But the parallels must also have been visible (or even more visible) in and around synagogues and communities after the Temple’s destruction. Although Tacitus denies the connection, to others Sukkot, arguably the only festival in the Jewish calendar in which materiality is at the core, invited “ethnographic” comparisons.

Especially the procession with the lulav must have looked to outsiders like a Dionysiac ritual. The lulav could be compared to the thyrsus: a rod covered with ivy and vine-leaves which was one of the attributes of Dionysus and his entourage of Maenads and Satyrs. The joyful feast of Sukkot when Jews built huts of vine and ivy and made processions accompanied by the sound of trumpets and other instruments reminded non-Jews of Dionysiac revelry.

The Thyrsus and the Lulav

In Greek cult the thyrsus, often understood as a phallic symbol of fertility, was also carried by priests of Dionysus. Remarkably a Jewish-Hellenistic author such as Flavius Josephus uses the Greek word thyrsos for the Hebrew lulav.[19] Now Josephus certainly did not intend to align the Sukkot festivities with rituals of Dionysus. But it is safe to assume that parallels between the Greek and Roman cult of wine and ecstasy on one hand and the Jewish festival rods on the other, were also noted by Jews.

Both Jews and pagans were aware of some parallels between the Jewish festival of booths and rituals of Dionysus. Was there some kind of Greek influence on Jewish Sukkot rituals? While this would be hard to prove, it certainly cannot be excluded either.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

September 21, 2018

|

Last Updated

February 2, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. René Bloch is Professor of Jewish Studies at the University of Bern (Switzerland), where he holds a joint appointment in the Institute of Jewish Studies and the Institute of Classics. He obtained his Ph.D. (Dr. phil.) as well as his “habilitation” from the University of Basel. Bloch’s most recent publications include: “Bringing Philo Home: Responses to Harry A. Wolfson’s Philo (1947) in the Aftermath of World War II,” “Dying in Egypt: Philo’s Joseph as a Cosmopolitan Citizen,” and “Jüdische Bibelkritik in Antike und Mittelalter: Von Philon von Alexandrien bis Spinoza.”

Essays on Related Topics: