Edit article

Edit articleSeries

A Sin Offering for Birth Anxiety

123rf

The Talmud relates the following exchange (b. Nidah 31b):

שאלו תלמידיו את רבי שמעון בן יוחי: מפני מה אמרה תורה יולדת מביאה קרבן?

R. Shimon ben Yochai’s student asked him: “Why does the Torah ordain that a woman following childbirth (parturient) should bring an offering?”

אמר להן: בשעה שכורעת לילד קופצת ונשבעת שלא תזקק לבעלה, לפיכך אמרה תורה תביא קרבן.

[R. Shimon] responded: “At the time when she squats to give birth she swears impetuously that she will not have intercourse (again) with her husband. Therefore, the Torah tells her to bring an offering.”

The students here are referring to the instruction in Leviticus 12:6 regarding the parturient:

ויקרא יב:ו וּבִמְלֹ֣את׀ יְמֵ֣י טָהֳרָ֗הּ לְבֵן֘ א֣וֹ לְבַת֒ תָּבִ֞יא כֶּ֤בֶשׂ בֶּן שְׁנָתוֹ֙ לְעֹלָ֔ה וּבֶן יוֹנָ֥ה אוֹ תֹ֖ר לְחַטָּ֑את אֶל פֶּ֥תַח אֹֽהֶל מוֹעֵ֖ד אֶל הַכֹּהֵֽן: יב:ז וְהִקְרִיב֞וֹ לִפְנֵ֤י יְ-הֹוָה֙ וְכִפֶּ֣ר עָלֶ֔יהָ וְטָהֲרָ֖ה מִמְּקֹ֣ר דָּמֶ֑יהָ…

Lev 12:6 On the completion of her period of purification, for either son or daughter, she shall bring to the priest, at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting, a lamb in its first year for a burnt offering, and a pigeon or a turtledove for a sin offering.12:7 He shall offer it before YHWH and make expiation on her behalf; she shall then be clean from her flow of blood…

What is her transgression? Though the sage’s answer about why she is bringing a sin offering for expiation was probably tongue in cheek, R. Joseph’s subsequent refutation shows that he had little patience for R. Simeon’s humor.[1] So the puzzle remains.

Purification Offering: Milgrom’s Theory

In modern biblical scholarship, Jacob Milgrom (ז”ל) took this case as further evidence for his view that the term חטאת should be rendered “purification offering” rather than as a “sin offering.”[2] I have argued, however, based on the term’s etymology, that we must leave the traditional translation as is.[3] But then we are left again with the problem, what was the sin?

The Dangers of Child Birth and Hittite Rituals

As is well known, giving birth posed considerable dangers to both mother and child in the premodern world, as is amply attested in the biblical and ancient Near Eastern textual record.[4] A key piece of evidence for our inquiry comes from the Hittites, inhabitants of a powerful kingdom in ancient Turkey.[5] Not only do the Hittite archives preserve a relatively large number of birth rituals from the 14th and 13th centuries BCE, many of these contain blood rites of smearing of blood on the birth seat, which is strikingly similar to the biblical sin offering involving the smearing of blood on the horns of the courtyard altar.[6]

It should be noted that in some other Hittite rituals, the blood smearing rite (called by the Hurrian term for blood, zurki) is performed on cultic objects, including cult statues.[7]Importantly, these rituals derive from the region of Kizzuwatna (classical Cilicia) in South-Eastern Anatolia, bordering on Northern Syria, a place where ritual traditions were exchanged between various ethnic groups in close proximity to the Land of Israel.

Kunzigannaḫit Purification: The 3rd Month for boys, the 4th for Girls

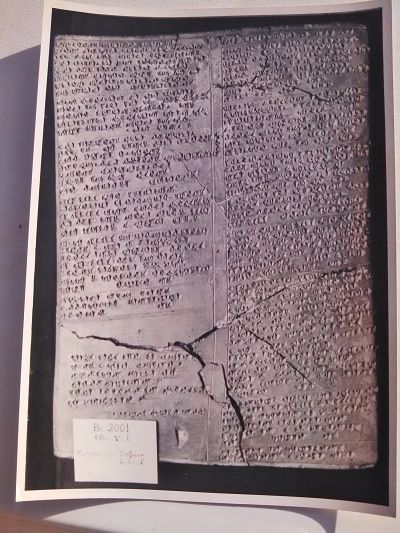

One Hitttite birth ritual contains a remarkably close parallel to Leviticus 12. This tablet (KBo 17.65) preserves two distinct versions of the same ritual on its two sides, and this unusual occurrence allows for confident reconstructions of many broken passages. Aside from the fact that it refers to a blood rite (zurki) to be carried out in the seventh month of pregnancy (Obv. 8; cf. Rev. 32), it contains an additional passage that is even more intriguing:

But (when) [the woman] gives birth, and while the seventh day is passing, then they perform the mala offering […] of the newborn on th[at] seventh day. Further, i[f a male child is bor]n, whatever month [he is bo]rn, whether [one day or] three [d]ays […] remain— [then from tha]t month let them count off. And when [the third month arrives,] then the male [child] they purify with kunzigannaḫit.[8] [For the seers] are expert with kunzigannaḫit. [And to … ] they offer it. But [if] a female child is born, [then] from that month they count off. When the [fourth] month [arriv]es, then they pu[ri]fy the female child with kunzigannaḫit.[9]

Aside from the obscure mala rite performed on the seventh day – reminiscent of the circumcision (מו”ל) performed for male offspring on the eighth day according to Lev 12:3, this passage delineates distinct periods of purification for the mother for male (3 months) and female (4 months) offspring, similar to Leviticus 12. Without going into a detailed analysis of this parallel,[10] it may be suggested that the biblical ritual may stem from a body of tradition attested in numerous Hittite birth rituals from Kizzuwatna.

The Papanikri Ritual – Dealing with Unknown Sins

Of particular interest is the ritual of Papanikri. This ritual deals with a case in which the birth seat (comprised of a basin and two pegs) breaks before the woman gives birth, an event that was interpreted as indicating divine anger, and as an ominous sign for the upcoming birth. Following the blood-smearing rite, the officiating priest declares

If your mother or father have sinned of late(i.e., they left over a sin), or you have just committed some sin… and the birth stool was damaged or the pegs were broken, O divinity, she has for her part made compensation (šarninkta) two times. Let the ritual patron be pure again![11]

This birth ritual explicitly addresses the possibility that the parturient has committed some sin, which has aroused divine anger. As such, it fits in with a large body of rituals and prayers from the ancient Near East that view adversity as a divine punishment, which could even be caused by unknown sins.[12] Strikingly, the verb šarni(n)k, which describes the effects of the blood rite, translated “made compensation,” is a precise semantic parallel to the Hebrew verb כפ”ר employed in the sin offering rituals.[13]

In light of this parallel, it can be suggested that the sin offering of the parturient in Leviticus 12 was similarly motivated by anxiety about giving birth, leading to a concern for possible unknown sins. To be clear, the biblical ritual in its current form suggests a purification after the birth, but the association of sin with birth in the Papanikri ritual – viewed in light of the additional parallels between the Hittite rituals and Leviticus 12, suggests that we take the biblical terminology (חטאת) seriously as an indication of the ritual’s origins.[14] This approach is analogous to other examples of the Priestly source’s reworking of earlier ritual traditions, as will be seen below.

Sin-Offering: An Anxiety Relief Ritual

Outside of these Near Eastern sources, the sin offering laws of Leviticus 4-5 also deal explicitly with cases of unknown sins, specifically those committed inadvertently (בשגגה; 4:2). The text refers to the matter being hidden (ונעלם דבר; 4:13, 5:2, 17-18) from the perpetrator, who only later finds out about the misdeed (ונודעה החטאת, או הודע אליו חטאתו; 4:14, 4:23, 4:28). These instructions raise some obvious questions: Why would someone bring an offering for an unknown crime? What were the circumstances in which these previously unknown sins became known?

Finding Out about Unknown Sins

While it is conceivable that, in some cases, other members of the community may have observed one of these misdeeds and rebuked the oblivious perpetrator,[15] it is doubtful that such a case was sufficiently regular to warrant this detailed set of instructions. A more likely background for Lev 4 would be in response to illness or personal distress, perhaps leading to an oracular inquiry (e.g. with the urim ve-tumim), such that the suffering itself or the results of this inquiry would serve as the basis for bringing a sin offering. However, this background is missing from the current form of Lev 4, raising the suspicion that it has been suppressed in a deliberate attempt to dissociate disease from sin.[16]

Leprosy as Divine Punishment

A similar tendency can be noted in the absence of any clear reference to sin in the rituals for “leprosy” (צרעת) in Leviticus 13–14, in stark contrast with other biblical sources that depict this disease as a divine punishment (Numbers 12:10; 2 Samuel 3:29 2 Kings 5:27; 2 Chronicles 26:19–20).[17] In particular, David’s curse of Joab, 2 Samuel 3:28–29, evokes skin disease and gonorrhea as punishments for Joab’s unjustified killing of Avner.[18]

וְֽאַל יִכָּרֵ֣ת מִבֵּ֣ית יוֹאָ֡ב זָ֠ב וּמְצֹרָ֞ע וּמַחֲזִ֥יק בַּפֶּ֛לֶךְ וְנֹפֵ֥ל בַּחֶ֖רֶב וַחֲסַר לָֽחֶם׃

“May there never cease to be in the house of Joab a gonorrheic (זב), leper (מצורע), a holder of the spindle, a victim of the sword or a person lacking bread,”

Strikingly, these two diseases required sin offerings according to Leviticus 14 and 15, though the latter chapters strangely make no direct reference to sin, treating these conditions as merely sources of impurity (טמאה). The plot thickens.

Shedding Ritual of Its (Original) Apotropaic Function

It seems that these anomalies can be explained as representing a general tendency apparent in the ritual laws of the Torah to deny any possible apotropaic (i.e. danger averting) function. Already in the early twentieth century (and without access to many of the ritual comparisons available today), Yehezkel Kaufmann (1899-1963) made the following cogent observations:

Now the distinctive feature of biblical purifications when compared with those of paganism is that they are not performed for the purpose of banishing harm or sickness. The pagan seeks to avert harm; his purgations are in effect a battle with baleful forces that menace men and gods. Biblical purifications lack this aspect entirely. Lustrations play no part in healing the sick. The woman who bears a child, the leper, the gonorrheic, the “leprous” house, are all purified after the crisis or disease has passed.[19]

As is most clearly seen with the laws of skin disease (צרעת), Priestly ritual does not perform any healing function, a radical departure from the widespread practice attested throughout the ancient Near East. Apparently, the exorcism of dangerous forces was incompatible with the Priestly worldview that considered God as in complete control over infection and healing.

In other words, the sin offering of the parturient can be viewed as a semantic fossil that harks back to an earlier time when these offerings were employed to address the potential dangers of giving birth. The preservation of this custom can be attributed to the conservatism of cult practices, as already recognized by Maimonides: “It is not possible (for a civilization) to move suddenly from one extreme to another.”[20]

Hence, by taking the term חטאת at face value as a “sin offering,” it is possible to reconstruct a lost phase in the prehistory of biblical religion. This awareness enables us to appreciate the continuity of biblical ritual with ancient Near Eastern practices, but also the subtle breaks with these traditions by which the Priestly source advanced its revolutionary worldview.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 5, 2016

|

Last Updated

January 1, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Yitzhaq Feder is a lecturer at the University of Haifa. He is the author of Blood Expiation in Hittite and Biblical Ritual: Origins, Context and Meaning (Society of Biblical Literature, 2011). His most recent book, Purity and Pollution in the Hebrew Bible: From Embodied Experience to Moral Metaphor (Cambridge University Press, 2021), examines the psychological foundations of impurity in ancient Israel.

Essays on Related Topics: