Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Part 4

Echoes of Maimonides’ View in Medieval Biblical Interpretation

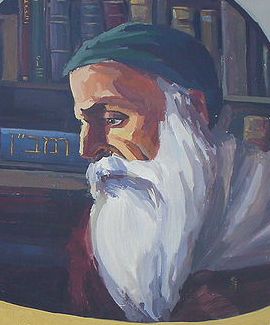

Nachmanides

A description of the writing of the Torah as dictation from God appears in two places in the Babylonian Talmud, which greatly influenced commentators on the Torah. Thus, for example, Nachmanides wrote in an introduction to his commentary on the book of Genesis:

But Moses wrote the genealogies of all the first generations as well as his own genealogy and experiences as a third-person narrator. Therefore it says ‘And God spoke to Moses and said to him’ (Exodus 6:10, etc.) as if it were speaking about two third parties. And because it is written this way, Moses is not mentioned in the Torah until he is born, and he is mentioned as if another were telling about him. And do not be troubled by the matter of Deuteronomy, in which he speaks for himself—‘I beseeched’ (Deuteronomy 3:23),‘I prayed to the Lord’(9:26),‘I said’(1:9, etc.)—for the beginning of this book is ‘These are the words that Moses spoke to all Israel’(1:1). Thus it appears to narrate speech in the words of the one who spoke. The reason the Torah is written this way is that it preceded the creation of the world, and needless to say the birth of Moses, in keeping with the kabbalah’s statement that it was written in black fire on white fire. Thus, Moses was like a scribe who copies from an ancient book, and therefore he merely wrote. But it is true and clear that the entire Torah, from the beginning of the book of Genesis to [the last verse in Deuteronomy,] ‘before the eyes of all Israel’ (34:12), was spoken by the Holy One blessed by He to Moses, as it says further on [where Baruch the scribe describes his writing the words of Jeremiah]: ‘He spoke all these things to me, and I wrote them on the scroll in ink’ (Jeremiah 36:18).

In this passage, Nachmanides contends with one of the obvious problems that the plain meaning of the biblical texts create for the “dictation” position. If Moses wrote the Torah, why is the book of Genesis narrated by an omniscient third person narrator, while the book of Deuteronomy is narrated by Moses in the first person? The solution that Nachmanides suggests is composed of two parts. In the first part, he explains that Moses is not mentioned in the Torah until the moment of his birth, “his entry into the story,” and that, therefore, the earlier parts of the Torah are narrated by an omniscient narrator. In the second part, he deals with the basic principle and explains that the entire Torah preceded the creation of the world and was dictated to Moses by God, and that, therefore, there was no gap between Moses’ field of knowledge and that which is written in the Torah.

It is important to note the elaboration of the view under discussion that takes place in Nachmanides’ words. The quoted passage opens with the statement “Moses wrote…,” and after this Nachmanides says that in fact the entire Torah preceded the world, and “needless to say the birth of Moses,” and that Moses wrote exactly what God said just as Baruch the scribe wrote exactly what Jeremiah said. The solution that Nachmanides proposes explains the changes in genre within the Torah in accordance with the Babylonian Talmud’s description of the dictation, and thus it creates a harmonized picture that obscures the contradiction between this description and the plain meaning of the biblical texts and the words of the Rabbis in various places. However, Nachmanides does not claim that all the verses of the Torah are equal.[1]

Abarbanel

Don Isaac Abarbanel (1437-1508), following Nachmanides, explains more broadly that the prophets themselves composed all poetic passages in the prophetic books. This is why they are attributed to them in the text.

From this you should know and understand that every poem found in the words of the prophets is something they composed themselves with divine inspiration and not something they saw in prophecy. . . Poetry is the prophet’s work, composed according to the holy spirit within him, not a vision shown to him in prophecy. Therefore, scripture always attributes [the poem] to the prophet who composed it, as it says in the Song of the Well, ‘Then Israel sang’(Numbers 21:17), [and likewise:] ‘Deborah and Barak son of Avinoam sang’(Judges 5:1), ‘The Song of Songs, which is Solomon’s’(Song of Songs 1:1); and Isaiah says, ‘I shall sing to my beloved’(Isaiah 5:1)—the song is attributed to him as the one who composed it. So, too, in the case of the Song of the Sea it says ‘Then Moses and the Israelites sang this song … and said: “I will sing to the Lord”’(Exodus 15:1), which is to say that they themselves composed it and sang it. Thus, at the end they prayed for their success: ‘May terror and dread descend on them, etc.’ (15:16), ‘You shall bring them and plant them, etc.’ (15:17)… It was thus with the Song of the Sea, which Moses composed to praise and laud the God who answered him in the time of his distress, and for this Miriam his sister also composed a song with tambourines and dance, as explained further on. Indeed, these songs were written in the Torah and in the words of the prophets because God received them and favored them and commanded that they be written there. If so, the composition of this song was by Moses, and its inclusion in the Torah was from God (Commentary on Exod 15).[2]

Abarbanel explains that the poetic texts in the Torah, the “songs,” were composed and sung by the prophets by divine inspiration but that their writing in the Torah and the prophetic books was by divine command, “from God.” He gives a similar explanation at the beginning of his commentary on the book of Deuteronomy, which is entirely composed of speeches by Moses and which, he says, was written in response to God’s command:

If the saying of these words to the Israelites was by Moses, peace be upon him, its writing in the Torah was not by him. For he, peace be upon him, did not write these words himself … if Moses spoke this whole book of Deuteronomy when he spoke to the Israelites, its writing was by God, and it was not written by Moses himself (Introduction to Deut.).

Distinguishing between Different Types of Biblical Texts

At this stage, it is worth paying attention to the fact that the Rishonim identified and distinguished between different genres and the different content that they communicate. For example, the opening ‘The Lord spoke to Moses, saying’is always understood as the narrator’s introduction to the binding legal content spoken by God, while the narrative portions of the Bible begin with ‘In the beginning God created’(Genesis 1:1), styled from the viewpoint of the narrator. These styles have different roles and statuses.

The poetic texts and the book of Deuteronomy attracted great attention because the sages sensed that the Torah did not present them as words that were spoken in the course of prophetic revelation. They discerned the singularity of the revelation at Sinai and similar revelations relative to the “regular” prophecy of Moses.

Nachmanides and Don Isaac Abarbanel, whose words we have just read, faced a difficult contradiction: a narrow reading of the Torah creates the impression that it includes different genres that differ from one another in the time they were spoken and in the mode of revelation in which they were spoken, in contrast to the dogma of dictation and equality. The solution they proposed was to distinguish between the process by which different parts of the Torah were created and the process by which they were written as part of the Torah. The different parts were revealed and took shape in a lengthy process and in various ways, each in a revelation unique and appropriate to it. After this, God commanded Moses to write these words in the Torah.

Or HaChaim – Chaim ibn Attar

At the beginning of his commentary on Deuteronomy, Or HaChaim (1:1), Rabbi Chaim ibn Attar (1696-1743) went far beyond Nachmanides and Abarbanel in his distinction between the words that Moses wrote himself and the words he heard from God:

‘These are the words, etc.’ These exclude the preceding, which is to be interpreted as follows: Because it says ‘which Moses spoke’, meaning that they are his own words, the entire book of rebuke is Moses’ reproof of those who transgressed the word of God. Our sages said (b. Megillah 31b) that the curses in Deuteronomy were spoken by Moses himself, and even where he repeated and interpreted the Lord’s earlier statements he was not commanded to do so; rather, he himself repeated the words. Scripture took pains to say this because [one might think] that just as Moses spoke such words himself, so too in earlier speeches Moses said some things himself. Rather, of everything in the preceding four books of the Torah he did not say even one letter himself, only the words that came from mouth of the Commander in their original form, without any alteration, even to add or remove one letter.

The words of ibn Attar are not consistent with the description of the dictation. He states simply that the entire book of Deuteronomy is Moses’ book, which he was not commanded to say but rather spoke of his own accord. In spite of his strong words about the other books of the Torah, of which Moses did not speak “even one letter himself,” ibn Attar recognizes the uniqueness of poetry and claims that after the appropriate preparation Moses himself recited the Song of the Sea:

‘Then [Moses] sang’: It did not have to say ‘then’, only ‘Moses sang, etc.’, and it would be understood that [Moses and the Israelites] sang then. However, scripture means to inform us of the preparation of the idea. For when the awe of [God’s] majesty and the full faith entered their hearts, then they merited to utter the song with divine inspiration (Or Hachaim, Exod. 15:1).

Beyond the Dictation Model

All the commentators presented thus far conformed their words to the “dictation” view, even though they sensed the different genres and the difficulties they pose for this position. But the assumption that the entire Torah was dictated by God to Moses was a matter of dispute among the Rishonim. Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra (1092-1167) alludes to this in several places,[3] and Rabbi Judah Ha-Chasid (1140-1217) says so explicitly in his commentary.[4] Rabbi Joseph ben Eliezer (Tov Elem) Bonfils (14th cent.), author of the Tzafenat Paneach (a supercommentary on ibn Ezra), went so far as to differentiate among the genres in the Torah (Gen 12:6), claiming that although the commandment sections were spoken by God, in the other genres the prophets were allowed to add their own words–though not an entire parasha (Gen 36:31-39)–in order to explain and interpret.[5]

It seems that Moses did not write this word here. Only Joshua or another of the prophets wrote it in prophecy to interpret his words … and because they had no qualms about this, it is clear that they had the authority to add words in order to explain. Thus, a fortiori a prophet must have the power to add a word to his speech, albeit only in the case of words that are not commandments but only narratives of things that happened. This is not called “addition.” And if you say, the sages said in Sanhedrin 10 that “even one who says ‘the whole Torah is from heaven except this verse, which was not said by the Holy One blessed be He but by Moses himself’ is included in ‘because he despised the word of the Lord’”—it must be answered that this refers to commandments, as we said above, and not to narratives.[6]

The words of R. Bonfils are generally quoted in order to show that the Rishonim already held that there are later additions to the Torah and that it continued to be edited by the prophets. However, the specific thing that he presents as “obvious” is the division of the Torah into different genres whose prophetic character is not uniform.[7]

If we return to Maimonides’ words, we discover something interesting. Although he claims emphatically that the verses of the Torah are equal to one another and were spoken by God, in formulating this claim he refers to the different genres: “he wrote all of it down—its dates, its narratives, and its commandments…” Our understanding that his view was written in opposition to the claims of the sectarians as part of a theological polemic is strengthened by his recognition of the different genres.

Maimonides may not have intended for his words to become the only description of the Torah. Perhaps his original intent was to teach the exalted and binding stature of all of our holy Torah, including all its components, against the sects that repudiated parts of it.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 14, 2014

|

Last Updated

February 9, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Rabbi David Bigman has been the Rosh HaYeshiva at Yeshivat Ma’ale Gilboa since 1995. Before becoming Rosh HaYeshiva at YMG, he served as the Rabbi of Kibbutz Maale Gilboa, and as the Rosh HaYeshiva in Yeshivat haKibbutz HaDati Ein Tzurim. He was one of the founders of Midreshet haBanot b’Ein Hanatziv.

Essays on Related Topics: