Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Giving Readers Access to the Divine: Temple Versus Tabernacle

A view of the the High Priest in the Tabernacle, George C. Needham, 1874. Library of Congress

Both Parashat Pekudei, Exodus 38:21–40:38, and its haftarah, 1 Kings 7:51–8:21, dwell in great detail on the construction of two different sacred spaces to “contain” God’s presence: the mishkan (tabernacle)[1] and Solomon’s temple. As anyone who has ever tried to build a model of the mishkan or temple shrine will find, the biblical blueprints lack key details.[2] Thus, they were not meant to be exact architectural plans, but rather thought pieces about the purpose of sacred space.

Whether historically accurate or not,[3] these literary descriptions invite us, the readers, to imagine these spaces, to visualize them, to even step within them mentally, and thus the texts provide us with an alternative means to divine access.

Mishkan: Temporary or Permanent?

The mishkan, described first in Exodus 25:1-31:17 and completed in Exodus 35:1-40:38, is a temporary and portable sanctuary built to “house” God—or his kavod (“presence,” as per Exod 29:43)—in the midst of Israel, as God himself requests (Exodus 25:8):

שמות כה:ח וְעָשׂוּ לִי מִקְדָּשׁ וְשָׁכַנְתִּי בְּתוֹכָם.

Exod 25:8 And let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them.

The key to this passage is not that God just wants a house to live in, but rather God desires an appropriate space in which the divine presence can interact with the Israelites.

The last verses of the parashah—and the book of Exodus as a whole—further illustrate the very problematics of the idea of God, or even the divine presence physically occupying the mishkan:

שמות מ:לד וַיְכַס הֶעָנָן אֶת אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד וּכְבוֹד יְ־הוָה מָלֵא אֶת הַמִּשְׁכָּן. מ:להוְלֹא יָכֹל מֹשֶׁה לָבוֹא אֶל אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד כִּי שָׁכַן עָלָיו הֶעָנָן וּכְבוֹד יְ־הוָה מָלֵא אֶת הַמִּשְׁכָּן.

Exod 40:34 The cloud covered the Tent of Meeting, and the Presence of the Lord filled the Tabernacle. 40:35 Moses could not enter the Tent of Meeting because the cloud had settled upon it and the Presence of the Lord filled the Tabernacle.

Here the cloud, a physical yet amorphous substance represents God’s presence, without giving God a physical form or earthly permanence. Yet its very presence prevents Moses, let alone the priests, from entering and fulfilling their ritual functions. If God resides permanently in the tabernacle, the ritual system as constructed by the priests falls apart.

Thus, this description of God’s indwelling speaks more to the writers’ wish to convey a larger theological claim for God’s continual presence, however imagined, among the Israelite readers of the text.[4] Moreover, its placement within the centermost point of the camp represents the ideal of God dwelling at the core of the Israelite nation.[5]

Permanent Home to the Tablets

Whether or not the tabernacle is meant to be envisioned as God’s or God’s kavod’s earthly home, the tabernacle is home to God’s Words, written in stone.[6] The very first instructions (which are then repeated several times) for building the tabernacle are for constructing the Ark to contain the stone tablets which is to reside there permanently:

שמות כה:כב וְנוֹעַדְתִּי לְךָ שָׁם וְדִבַּרְתִּי אִתְּךָ מֵעַל הַכַּפֹּרֶת מִבֵּין שְׁנֵי הַכְּרֻבִים אֲשֶׁר עַל אֲרֹן הָעֵדֻת אֵת כָּל אֲשֶׁר אֲצַוֶּה אוֹתְךָ אֶל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.

Exod 25:22 There I will meet with you, and I will impart to you—from above the cover, from between the two cherubim that are on top of the Ark of the Pact—all that I will command you concerning the Israelite people.

When God visits, God sits above the ark; and the cherubim, which are on top of it, serve as God’s throne when he holds audiences with Israel. God comes and goes, but the ark, containing the people’s divine covenant, remains a fixed and necessary foundational structure, within.

God’s Accessibility in the Real versus Textual Mishkan

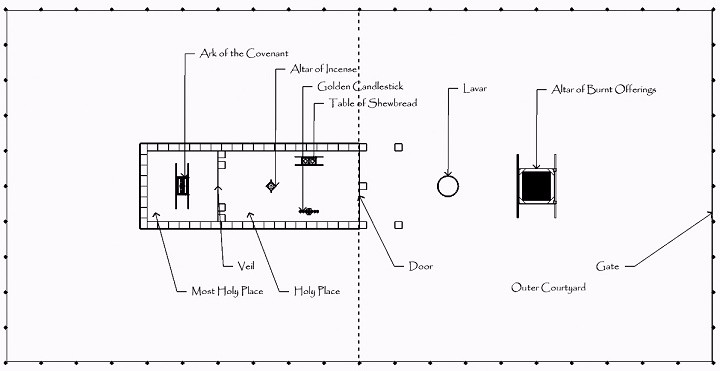

These biblical descriptions of God speaking from within his tabernacle hidden by a cloud raise a tension around divine accessibility. As we saw at Sinai, though God can speak directly to the people, it is best if his words are filtered through Moses (Exod 20:16). In ancient Near Eastern cultures, a sanctuary was not a place of community congregation—it is not a synagogue—but a cultic site where a deity is both “housed” and worshipped. Similarly, the mishkan is divided physically between these two occupations: indwelling, in which God is separated from the people, and worship, in which God is more accessible to the people.

The sacrificial altar and the ark each sit at the center of the two side-by-side squares that make up the tent of meeting. The priests face the ark and God “faces” out to the priests/people from his position on top of the ark.[7] But the lion’s share of the people (everyone but the priests) stand outside the mishkan; they stand beyond the boundaries of the tent of meeting, even as they supply the sacrifices. While the Presence of God remains visible to the people in the camp in the form of the cloud, the cultic activities in the mishkan are accessible only to the priests. The people do not “see” God in the same manner that Moses and the priests do within the tent of meeting.

The Reader’s Direct Access

We, the audience of this literary divine tableau, in contrast, can “see” directly into the mishkan through the text’s descriptions, and we affirm, through this vision, that God stands by (or on) his word, as we the people send our devotion his way. Had we been present at this moment, we would have been lost among the throngs of Israelites, but as readers, we get front row seats to God’s presence. Moreover, as Amy Cooper-Robertson notes, the very repetitive nature of these descriptions, particularly of the cultic activities within the mishkan, invites the reader to engage more intimately, and I would argue, more democratically, with the idea of accessing the divine meditatively within this imagined sacred space.[8]

Temple Narrative – God’s Covenant with David

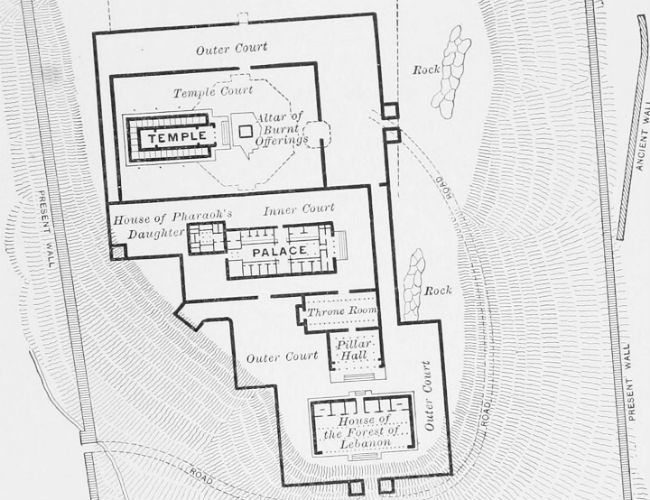

The mishkan, while executed by the people under Moses’ supervision, was fully designed by God (e.g. Exod 25:8-9). In contrast, Solomon’s temple is conceived, designed and built by Solomon. According to 1 Kings 8:27, Solomon wisely questions whether it is truly possible to design a house for God, given that “even the heavens to their utmost reaches cannot contain You!” Nevertheless, Solomon does just that. Moreover, the king engages a foreign monarch to supply the wood and forces numerous Israelites to labor on this infrastructure project’s behalf (which includes Solomon’s palace, a construction more than twice the temple’s size).[9]

Although we have no material remains of Solomon’s temple, the temple design, as outlined in the text, closely resembles other known ancient Near Eastern sanctuary structures. These buildings contain a tripartite pattern and connect to larger royal complexes.[10] Nevertheless, the text claims, by invoking the same cloud that filled the mishkan, that God surely approves of the new divine home even as he had no hand in creating it:

מלכים א ח:י וַיְהִי בְּצֵאת הַכֹּהֲנִים מִן הַקֹּדֶשׁ וְהֶעָנָן מָלֵא אֶת בֵּית יְ־הוָה. ח:יא וְלֹא יָכְלוּ הַכֹּהֲנִים לַעֲמֹד לְשָׁרֵת מִפְּנֵי הֶעָנָן כִּי מָלֵא כְבוֹד יְ־הוָה אֶת בֵּית יְ־הוָה.

1 Kgs 8:10 The priests came out of the sanctuary—for the cloud had filled the House of the Lord 8:11 and the priests were not able to remain and perform the service because of the cloud, for the Presence of the Lord filled the House of the Lord.

This building, designed to “house” God also contains the ark. Verse 8:8 notes in particular that the poles, upon which the ark was carried throughout the wilderness, were too long for the shrine, and stick out of the devir (inner sanctum or holy of holies) into the nave or “main” sanctuary.[11] The poles thus remind the viewer—and the reader—of who or what is behind the curtain.

The Solomonic dedication ceremony, read by Ashkenazim as the haftarah for Pekudei, thematically matches the mishkan’s at the end of Pekudei. In both cases, God, represented by the cloud, descends into the newly constructed structure and occupies it fully, sending the personnel outside. Yet, as opposed to the dedication of the mishkan, which was witnessed by all of Israel after they had all participated in its construction, at the temple’s dedication, the congregation of Israel is further distanced from Solomon’s shrine by the expanded hierarchy of (male) leaders involved in its dedication.

While the temple narrative in Kings invites all Israel as readers to “witness” Solomon’s dedication, the Deuteronomistic authors establish through this “cloud descending” ceremony that the Davidic dynasty is particularly blessed. The text focuses on God’s promise to David (1 Kings 6:12-13 and 8:15-21) and the concomitant need of the Davidic kings’ obedience to God’s covenant.

These authors were no doubt writing to support a theological and political agenda that promoted the Jerusalem court and shrine over any other Israelite “pretenders.” Solomon goes out of his way to claim God’s full support for his kingdom and his centralizing shrine, thereby invalidating all other shrines.[12] The ark in the temple, evidence of the people’s covenant with God, comes merely as supporting evidence for God’s covenant with David and his promise of an everlasting dynasty. Thus, the text betrays a tension between the people’s covenant and the king’s; in Solomon’s temple, the people’s covenant remains secondary to the Davidic covenant.

Mishkan Narrative – God’s Covenant with Israel

The mishkan narrative is also part of a larger agenda, supporting Israelite allegiance to God and the divine covenant, with no king involved. The whole of the Torah can be seen in this light: the law, embedded in an extensive narrative of a nation’s contractual relationship to God. The mishkan represents the culmination of that budding relationship, providing the space in which this God dwells among this nation. Thus, the mishkan narrative focuses its attention on the full obedience of the people to God’s instructions and the enthusiastic ways in which they fulfill them.

Culmination of Creation

This scene is also framed by subtle references back to the Creation narrative.[13] First,Vayakel starts with a call to celebrate/observe the Sabbath; second, the text lays out the mishkan’s building instructions, mostly making use of the same term (עשה, “to make”) used in the creation story; and finally, when the people finish the construction the text of Pekudei reports:

שמות לט:לב וַתֵּכֶל כָּל עֲבֹדַת מִשְׁכַּן אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד וַיַּעֲשׂוּ בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל כְּכֹל אֲשֶׁר צִוָּה יְ־הוָה אֶת מֹשֶׁה כֵּן עָשׂוּ.

Exod 39:32 Thus was completed all the work of the Tabernacle of the Tent of Meeting. The Israelites did so; just as the Lord had commanded Moses, so they did.

God said, “build,” and so it was built. Moreover, the last event of this book is a ceremony of dedication, on the first day of the first month, indicating that with this new shrine and manifest obedience, the people have entered a new day, a new era, a new life with God.[14]

The Mishkan as a Response to the Temple

In late biblical writings (the prophets, psalms), Jerusalem and God’s holy mountain, upon which the Temple stood, are certainly viewed positively as eternal entities, but not everyone saw the Jerusalem Temple as legitimate or inclusive—the people of the Northern Kingdom certainly did not see it in that light. From construction to destruction the First Temple was a site of contention. The northern tribes built or returned to their own shrines. Southern kings abused their royal prerogatives over the Jerusalem shrine. Surely resentments built in many quarters outside the royal inner circle.

Thus, by the time the mishkan texts come together, a history of discontentment, particularly among the priestly class, most likely already existed for generations. While the mishkan precedes the Temple in the narrative arc of the Bible, this particular description, as found in our Exodus text, is most likely a product of post-temple writers, and comes as a corrective to the Temple narrative with its focus on the Davidic covenant.[15]

An Ideal of Inclusion

The mishkan description in Exodus, whatever fact or memory it may be based on, presents a reworked utopian ideal. An ideal of a perfect God dwelling among an obedient people is spelled out in the mishkan’s exacting, divinely-instructed blueprint, and in its faithful-to-the-letter execution, not just by the leaders of Israel, but by all of Israel.

Israelite sacred space, although primarily created to “house” God on earth, can only function as that unifying spiritual space for Israel when all Israelites feel included. And though the mishkan has its own hierarchies of access (God—Moses—priests—people), the literary depiction in Exodus, in contrast to Solomon’s more isolated royal shrine, opens access to all readers (Israelites) through its detailed visualizations of God’s presence, whether in the cloud or sitting above the cherubim.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 19, 2017

|

Last Updated

February 1, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Naomi Koltun-Fromm is Associate Professor of Religion in Haverford College. She holds an M.A. and Ph.D. in Jewish Studies from Stanford. She is the author of Hermeneutics of Holiness: Ancient Jewish and Christian Notions of Sexuality and Religious Community.

Essays on Related Topics: