Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Symposium

Pharaoh’s Mudbrick Palace

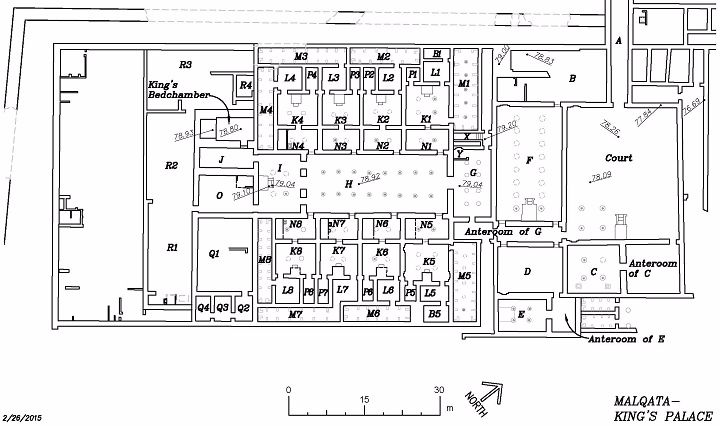

An aerial view of the ruins of the Malqata palace of Amenhotep III, on the west bank at Thebes (c. 1350 BCE). Wikimedia

The “Great House” of Pharaoh

Throughout the account of the plagues, Moses meets with Pharaoh numerous times. Sometimes the Torah specifies that they meet at the Nile,[1] but other times the meeting place is unspecified (Exod 5:1, 10:1, 11:8). In visualizing these encounters, you’ve probably imagined some of it taking place in the Egyptian royal palace. Big-screen adaptations of the story have certainly taken the liberty to set many interactions with the pharaoh in the palace throne room, where the king usually met visitors.

Why the Torah never explicitly mentions Moses and Aaron entering the palace is unclear. Perhaps the association between the king and the palace was clear enough that the reader was meant to understand implicitly that this is where conversations were taking place.[2] In fact, as Shirley Ben Dor Evian writes in "The Title 'Pharaoh,'" the term pharaoh is a bastardization of per a’aa, meaning “great house,” which is to say, the palace. Calling the king of Egypt the “pharaoh” is a metonymy, like “White House,” “Vatican,” or “Buckingham Palace,” which uses an iconic location to refer to a governing entity. The actual term for king in Egyptian is nesu(t) bity.

Horus Name on a Palace Façade

Pharaohs were given five royal names. One of these names, called the “Horus name,” which often appears underneath an image of the falcon god Horus, is written inside a palace façade motif called the serekh (Fig 1). This writing style expresses the idea that the king and his place of residence were intrinsically linked.

Multiple Palaces

The ruler of Egypt had no single palace, and, instead, like a medieval ruler, moved around the country to perform his or her—there were female pharaohs—duties. The court likely accompanied the king along the circuit. During the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE) period, palaces were built in each of the two capitals, Memphis in the north and Thebes in the south. We do not know, however, how many palaces any given ruler had—the archaeological record has not preserved that information.

Mud-brick Palaces

In contrast with elite tombs and temples, residences in ancient Egypt were built of mud brick, and the palace was no exception. Although the king was the most important person and the residence would have been a locus of much activity, tombs and temples were built of stone and meant to last for eternity, while palaces were not designed with such longevity in mind. Consequently, surviving palaces (or living spaces of any kind) are few and far between.[3] Their construction was an acknowledgment that ancient Egyptian lives were brief. Kingship was eternal, but the people who held that office were mere mortals.

The best-excavated examples of palaces are from the eighteenth dynasty (Fig. 2), in the New Kingdom, about 1500-1300 BCE. Several palaces have been at least partially preserved from this period:

Malqata – The Malqata complex of Amenhotep III on the west bank at Thebes (c. 1350 BCE), was built or rebuilt for the ceremonial purpose of celebrating the king’s jubilee, around the thirtieth year of his reign.

Amarna – The so-called Great and North palaces of Akhenaten at Amarna in Middle Egypt (c. 1370 BCE) are relatively well-preserved owing to their desert location. These Amarna palaces, however, were built hastily and quickly abandoned. Also, the atypical ideology at this time does not allow us to generalize.

Merenptah’s palace – The palace of nineteenth-dynasty king Merenptah[4] (c. 1200 BCE) at Memphis is the most likely of the three to represent “standard” palaces. Nevertheless, we should exercise caution in over-generalizing even here, given the millennia-long duration of Egyptian kingship.

A Tour of the Palace: Common Features

Each palace shared common features, with some variation: the visitor would have first entered into an open court enclosed by columns and statues. At Amarna, the courtyard may have contained a so-called window of appearance where the king and his principal consort (the Egyptian equivalent for “queen” was “great royal wife”) appeared before crowds. Palaces generally contained or were near pools that replicated the Nile marshes, metaphors for the cosmos.

As the visitors moved toward the rear of the palace, they would enter at least one columned hall; larger palaces may have contained several halls. Before entering the throne room the visitor passed through a transverse hall, a rectangular space often wider than or perpendicular to the spaces that proceed and follow. The farthest into the palace a visitor would venture would be the throne room, where the king received visitors. The king enthroned was a vital image, and the entire palace was symbolic of the ruler’s authority.

The New Kingdom palaces are, as with most Egyptian architecture, quite symmetrical. Often, on either side of the central courts and halls, storerooms were tucked away. The king’s chambers, where he had his most private interactions, were typically toward the back, behind or near the throne room, farthest from the courts in front. Spaces nearer to the entrance were presumably more public, though again, the issue of how public “more public” would have been is difficult to say—surely any random Egyptian could not have just walked in.

Variation

The extant palaces are not all identical. Malqata and the Great Palace at Amarna are complex city-palaces with housing for officials and royal family members, alongside ceremonial and administrative buildings. The Merenptah palace is much smaller and simpler in design. It also happens to be the most accessible since some of its architectural elements are on display at the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

Thrones

Some furniture from royal contexts has survived; King Tut’s tomb, of course, offers the best examples. It was full of thrones, beds, chests, and other objects that might have been put to use inside the royal residence.[5] The throne is particularly significant as a piece of furniture unique to kings and palaces.

Thutmose IV

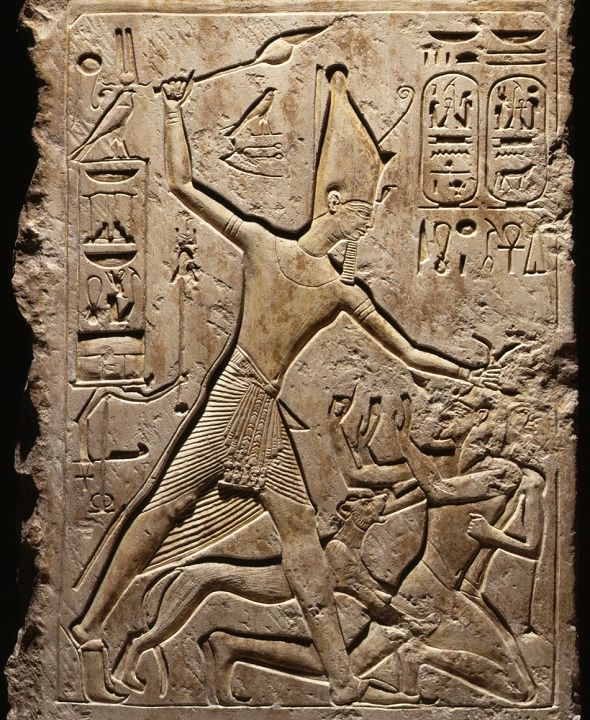

Surviving thrones replicate the themes of natural and military order also found in palace decoration. A throne panel from the tomb of Thutmose IV (c. 1400 BCE), now in the Metropolitan Museum, shows the king as a sphinx, trampling enemies from abroad (Fig. 3). On the other side of the panel, he is enthroned, marking a chicken-and-egg relationship between the former action and latter status; he tramples foreigners because he is the king, but he is the king because he is powerful enough to trample foreigners. The images work together to portray a powerful ruler dominating Egypt’s enemies. The panel itself was originally gilded, furthering the illusion of the king’s divinity.

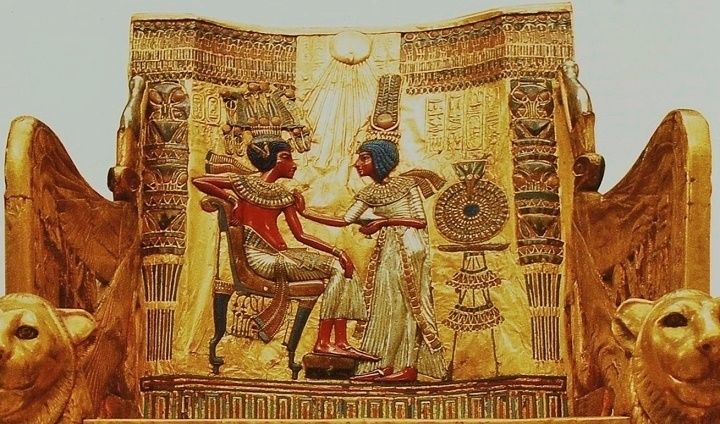

Tutankhamun

The golden throne of King Tut depicts him being anointed by his queen, Ankhesenamun (Fig. 4). It looks like an intimate gesture to modern viewers, but more important than an emotional connection is the suggestion of sex, which would ensure the conception of the next king and, along with (ideally) him, the continuity of Egyptian society.[6]

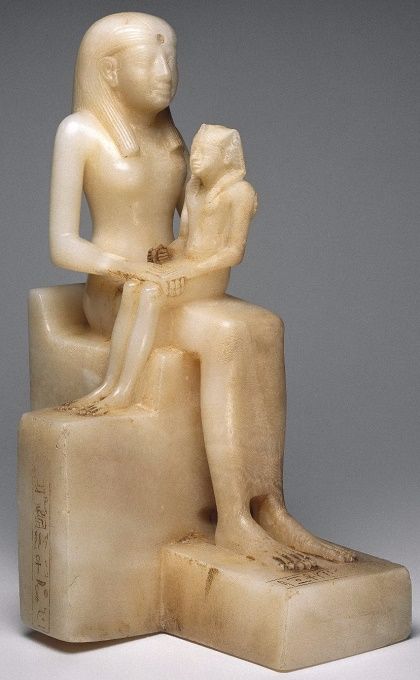

Pepi II

In a statuette in the Brooklyn Museum, Pepi II (c. 2280), who became king at the age of 5 or 6, sits on the lap of his mother, Ankhnesmerira, who is herself enthroned, and whose body takes the form of the throne on which the king is seated. The figure shines in glowing, milky calcite (Fig. 5).

It is unlikely that this was meant to depict a real moment or that a visitor would have encountered the king on his mother’s lap in the throne room. Instead, the image may represent the queen’s status as regent. The radiance of the figure expresses how the king seated within the palace echoed his role within the cosmos: a beacon at the center, its most important aspect. The structure of the palace, along with its decoration and fittings, was a model of this worldview.

Palace Decoration: Surviving Evidence and Notable Themes

Studying the scant architectural remains and extant decoration alongside artistic representation gives us some insight into how Egyptian religious beliefs were incorporated into the performance of kingship.

Fragments of painting from New Kingdom palaces mainly depict the natural world, chiefly plants and animals. Humans and deities are largely absent from these paintings. This flora and fauna, especially that associated with the Nile marshes, were metaphors for the cosmos and the creation cycle; the inclusion of the pools within palace compounds reiterates that. The artistic program of surviving palace decoration is meant to reflect and enhance the king’s role as maintainer of this natural order.

The King Ensures the Natural Order (Ma’at)

The dependable order of the natural world was essential to the safety and prosperity of ancient Egypt. It was the king who was responsible for keeping the dangers in check and ensuring that life could be sustained.[7] To do this, the king performed temple rituals while in Egypt and managed Egypt’s affairs abroad. In addition, the Egyptians belief in ḥeka (a magical force permeating the universe) included the idea that images could have an active effect.[8] Thus, the king was often depicted subduing foreigners in art to magically neutralize them.[9]

These themes carry into palace design. A relief from the Merenptah palace now in the University of Pennsylvania Museum shows the king smiting an enemy(Fig. 6). Faience tiles from the twentieth-dynasty funerary complex of Ramses III at Medinet Habu (c. 1175 BCE) in the Museum of Fine Arts depict bound Nubians rendered helpless by the king of Egypt (Fig. 7).[10] Egyptian tomb paintings show the enthroned king surrounded by images of subdued foreigners.[11] A facsimile of one scene from the tomb of Anen rendered by Nina de Garis Davies, for example, shows Amenhotep III and his principal wife enthroned on a dais decorated with all of Egypt’s enemies bound, literally under the king.

Foreigners in the Palace

As with so much in Egyptian visual representation, though, the subjugated foreigner is an ideal image that did not always reflect political realities. Egypt did not eternally dominate its neighbors. In fact, foreign invasions disrupted Egypt at several points and foreigners ruled Egypt as kings at various epochs. Moreover, Egypt maintained peaceful and political relations with many foreign nations at any given time, and foreign diplomats would have visited Egypt.

Presumably, foreigners visiting the palace would have seen these images of prostrate foreigners, being magically destroyed by their Egyptian hosts. In many ways, this depiction is similar to the U.S. presidential seal that bears an eagle with a talon clutching arrows: presumably, foreign leaders meeting with the president do not interpret this image literally, but rather take their cues from the words and actions of their American counterpart, rather than his iconography.

The Meaning of a Temporary but Lavish Palace

Palace decoration displayed the king’s taste, wealth, power, and Egypt’s values to any visitor, but this was not its sole purpose. The decoration and outfitting of Egyptian palaces instead reflected the Egyptian belief systems and may have magically helped to ensure the sustenance of these principles.

Although the royal palace served as a residence and seat of the central bureaucracy, the main point of the structure, as reflected in its art, was depicting the king as the maintainer of ma’at (order). Thus, the royal residence was more than just a pragmatic and necessary structure—it also played an important role in ensuring the king’s authority.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 10, 2017

|

Last Updated

January 6, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Rachel P. Kreiter earned a doctorate in art history from Emory University in December 2015 and has written about arts and culture for various publications, including Burnaway and the Awl. Their research interests include ancient Egypt in its myriad contexts, including the African continent, ancient Near East, contemporary art, and museums.

Essays on Related Topics: