Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Sect that Plucks out the Sinews: Kaifeng Jews

East Market Street, Kaifeng, 1910; the Synagogue was just past the shops on the right. Wikimedia (adapted)

On his way home from Laban, on the night before he is to meet Esau, Jacob wrestles with a “man” by the Yabbok Stream:

בראשית לב:כה וַיִּוָּתֵר יַעֲקֹב לְבַדּוֹ וַיֵּאָבֵק אִישׁ עִמּוֹ עַד עֲלוֹת הַשָּׁחַר.

Gen 32:25 Jacob was left alone. And a man wrestled with him until the break of dawn.[1]

The name Yaakob (“Jacob”) is echoed in the place name Yabbok where the incident takes place,[2] as well as the significant term (א.ב.ק) “wrestling.” During the altercation, Jacob’s opponent injures him:

לב:כו וַיַּרְא כִּי לֹא יָכֹל לוֹ וַיִּגַּע בְּכַף יְרֵכוֹ וַתֵּקַע כַּף יֶרֶךְ יַעֲקֹב בְּהֵאָבְקוֹ עִמּוֹ.

Gen 32:26 When the man saw that he could not overpower him, he touched the socket of Jacob’s hip so that his hip was wrenched as he wrestled with the man.

Even injured, Jacob does not let go. At dawn, when and the man is still being held by Jacob, he asks to be released, but Jacob refuses to do so until the man blesses him, a way of ensuring that the man would not attack him again once let go.

The Name Israel

The man responds by confessing to be a divine being and renames Jacob “Yisrael (Israel),” literally “El will rule,” but here, invoking a midrash shem or folk etymology that reflects Jacob’s ongoing struggle on the spiritual and human planes:

בראשית לב:כח וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלָיו מַה שְּׁמֶךָ וַיֹּאמֶר יַעֲקֹב. לב:כט וַיֹּאמֶר לֹא יַעֲקֹב יֵאָמֵר עוֹד שִׁמְךָ כִּי אִם יִשְׂרָאֵל כִּי שָׂרִיתָ עִם אֱלֹהִים וְעִם אֲנָשִׁים וַתּוּכָל.

Gen 32:28 So he said to him, “What is your name?” And he said, “Jacob.” 32:29 Then the man said, “You shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with humans and have prevailed.”

At this point, Jacob asks the being who he is, but the angel deflects (v. 30). Jacob then names the place Penuel, “Face of God,” to capture his experience there (v. 31). When he finally leaves, Jacob is limping, and the Torah explains that this is the reason that Israelites do not to eat the גיד הנשה (gid hannasheh), the sciatic nerve:

בראשית לב:לב וַיִּזְרַח לוֹ הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ כַּאֲשֶׁר עָבַר אֶת פְּנוּאֵל וְהוּא צֹלֵעַ עַל יְרֵכוֹ. לב:לג עַל כֵּן לֹא יֹאכְלוּ בְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶת גִּיד הַנָּשֶׁה אֲשֶׁר עַל כַּף הַיָּרֵךְ עַד הַיּוֹם הַזֶּה כִּי נָגַע בְּכַף יֶרֶךְ יַעֲקֹב בְּגִיד הַנָּשֶׁה.

Gen 32:32 The sun rose upon him as he passed Penuel, limping on his hip. 32:33 That is why the children of Israel to this day do not eat the sciatic nerve[3] that is on the socket of the hip, since Jacob’s hip socket was wrenched at the sciatic nerve.

The name Israel is thus tied to the practice of not consuming the sciatic nerve.

What Does the Prohibition Signify?

While the Torah’s grounding of this dietary rule in a patriarchal story is unusual—no other dietary rules receive a backstory in the Torah—commentators still debate its exact significance.

Jacob’s Prowess and God’s Miracle—Rashbam (R. Samuel ben Meir, ca. 1085–1158) suggests that it is a memorial to Jacob’s prowess:

רשב"ם בראשית לב:לג "על כן לא יאכלו" – לזכרון גבורתו של יעקב ונס שעשה לו הקב"ה שלא מת.

Rashbam Gen 32:33 “That is why they don’t eat”—in commemoration of Jacob’s prowess, and the miracle that the Blessed Holy One performed for him, that he didn’t die.[4]

The Need to Protect Others—R. Ḥezekiah ben Manoaḥ (13th cent) says that Jacob’s sons should have been with their father to protect him, and the prohibition is a reminder to do better:

חזקוני בראשית לב:לג ...בדין הוא שיש לקנוס ולענוש בני ישראל מאכילת גיד הנשה שהניחו את אביהם הולך יחידי, כדכתיב ויותר יעקב לבדו (בראשית לב:כה), והן היו גיבורים והיה להם להמתין אביהם ולסייעו אם יצטרך....

Ḥizkuni Gen 32:33 …It was fitting to fine and punish the children of Israel by forbidding them from eating the gid hannasheh, for they left their father on his own, as it says (Gen 32:25) “And Jacob remained on his own.” But they were warriors, and they should have waited for their father and assisted him if he needed it…

Surviving Adversity—The anonymous Sefer Ha-Ḥinukh (13th cent.) suggests that it is a reminder that Jacob’s descendants will always survive adversity:

ספר החינוך מצוה ג משרשי מצוה זו, כדי שתהיה רמז לישראל שאף על פי שיסבלו צרות רבות בגליות מיד העמים ומיד בני עשו, שיהיו בטוחים שלא יאבדו, אלא לעולם יעמוד זרעם ושמם, ויבוא להם גואל ויגאלם מיד צר.

Sefer Ha-Ḥinukh §3 At the root of this commandment is for it to serve as a hint to Jews that even though they will suffer many tragedies in the Diaspora at the hands of nations, and the hands of the children of Esau (=Christians), they should be confident that they will not be destroyed, rather their descendants and their name will always remain, and a redeemer will come to redeem them from the enemy.[5]

Minimizing Adversity—In contrast, R. Ovadiah Seforno (ca.1475–ca.1550) understands the removal of this unimportant part of the animal as an attempt to symbolically minimize future adversity:

ספורנו בראשית לב:לג "על כן לא יאכלו בני ישראל" – כדי שיהיה ההיזק אשר הורה בנגיעת כף הירך היזק בדבר בלתי נחשב אצלנו.

Seforno Gen 32:33 “That is why the children of Israel do not eat”—in order that the damage foreshadowed [by the angel] by touching [Jacob’s] hip socket end up being to something unimportant to us.

While these and other interpretations try to make sense of the prohibition’s meaning, in practice, the rules of gid hannasheh have seemingly played little to no role in Jewish identity and self-conception. One stark, if obscure, exception is the Jewish community in Kaifeng who literally named themselves after this prohibition.

A Brief History of Kaifeng Jews

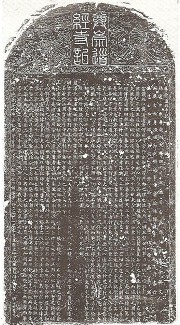

We do not know when Jews first appeared in China.[6] The main historic sources for the Jewish community in Kaifeng are the four commemorative stelae that were erected in the synagogue courtyard, dating from 1489, 1512, 1663, and 1679. Two of them mention Jews arriving during the Han Dynasty (212 B.C.E.–220 C.E.).[7] This implies that they arrived in the wake of the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E., but the overall evidence of Jewish settlement in China pushes against the facticity of this claim.

A Persian Jewish document dates Jewish presence in China, if not specifically Kaifeng, to the 9th century.[8] The Jews who settled there probably originated from Persia or Bukhara[9] and took part in commerce along the Silk Route. The Kaifeng synagogue was first built in 1163 C.E., which establishes its beginnings during the Sung Dynasty (960–1279), a period of international commerce, with Kaifeng as its capital city.[10]

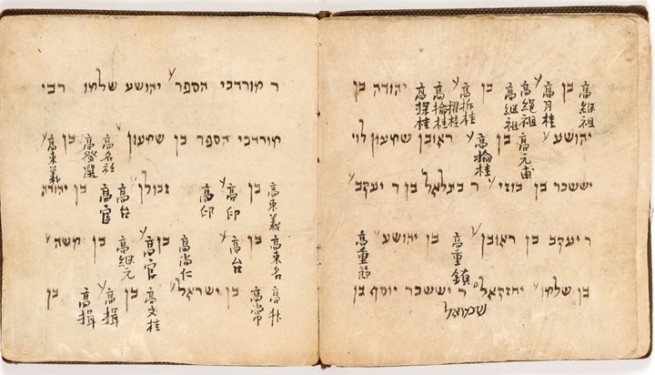

The miniscule Kaifeng Jewish community—no more than a few thousand individuals at any given time—were cut off from the main centers of world Jewry in the Middle East and Europe and had to rely on their own resources to maintain their identity in China. Thus, among the merchants and traders were also those proficient enough to be rabbis, teachers, prayer leaders, Torah scribes, and ritual slaughterers. And the community members were both bilingual and proficient in two entirely different writing systems.

While they adhered to rabbinic practice and had some knowledge of classic traditions, especially the story how Abraham found God,[11] we do not know if they had rabbinic texts such as the Mishnah and Talmud in their possession. The commemorative stela, noted above, written in Chinese, describe their origins as far back as Adam and the first Patriarch Abraham, and served as the community’s foundation story, relating an abbreviated biblical history and describing the semblance between their religious beliefs and Chinese values.

The Assimilation of the Community

In China the Jews were allowed to practice their beliefs and live their communal life unhindered by anti-Semitism, a mixed blessing since it led eventually to full assimilation and the disappearance of the community. The Jewish men took local women as wives and concubines, which weakened their Jewish family traditions. By 1605, when the Jesuit missionary Mateo Ricci, the first Westerner to document a meeting with a Kaifeng Jew, met with the scholarly Ai Tien, the Jews had become racially Chinese.

Similarly, the upward mobility of some of these Jews in their pursuance of a career in the Chinese civil service and military further increased the process of assimilation, since this career choice demanded a proficiency in Confucianism and a loyalty to its values—the required deportment and eating habits—as well as the necessity of serving away from one’s hometown, often in places with no Jewish community.

As the centuries progressed, the Jewish community could no longer produce religious scholars, teachers, and laymen versed in the Hebrew language and religious practice. One by one, the community’s Torah scrolls, prayer books, religious artifacts, commemorative stelae, and the synagogue land itself were sold off.

The community disappeared around the early 19th century,[12] having succumbed to the benevolent process of assimilation. Today, we find only the cloudy memories of the so-called “descendants” of the Kaifeng Jews - those individuals who on the basis of family traditions and specific patrilineal surnames, claim that they have Jewish roots, calling themselves “Descendants of the Jews.”[13]

The Message of Names

The Kaifeng Jewish community was known by different names in dynastic China, proposed either by the Jews or given by the Chinese, documented in the four synagogue stelae referenced above, as well as in the accounts of the early Jesuit missionaries who visited them from 1605 onward.

Yi-ci-le-ye—the Chinese transliteration of Yisraeli “Israelite.”

The Blue Hat Muslims—an ethnic marker to distinguish Jews from Muslims who were called “White-Hat Muslims.” In many respects, the Jewish community was quite similar to the Persian-Muslim community. Both religious groups were monotheistic, avoided pork consumption (the main meat staple of the common Chinese diet), circumcised, prayed multiple times a day facing west, and read from scriptures written in an alphabetic script. In addition, both groups were Western in appearance and race, at least at first and the Jews even spoke and wrote some Persian,[14] though in the Hebrew script. This made it virtually impossible for the Chinese to tell the two apart, so they latched onto the different head coverings, an obvious enough feature.

Tiao-Jin-Jiao (挑筋教) “The Sect that Plucks out the Sinews”—a reference to the Torah prohibition to consume the sciatic nerve.

What is your name? (Gen 32 28)

Occupational names based on the preparation of kosher meat were common among most Jewish communities. Surnames like Shochet, Schechter, Fleishman and Katzav refer to a standard ritual slaughterer or butcher, while the surname שו"ב Shub, an abbreviation for שוחט ובודק (shoḥet u-bodeq), i.e., “a slaughterer and examiner,” emphasizes the more technical knowhow required for checking the lungs of a slaughtered animal for adhesions that might render it unfit for kosher consumption.

Even more specialized were butchers trained to remove the sciatic nerve, located at the thigh muscle, from slaughtered bovine animals, in a process called niqqur “removal of forbidden fat and veins.” The specialist butcher who could remove the nerve was called a מנקר menaqqer, in Yiddish a treyber, [15] both of which also became honorific family names.[16]

But this makes sense for family names, with pride in the patriarch’s background as a specialist menaqqer. But why of all things did this Jewish community in Medieval China choose to note this practice as the distinctive feature for self-identification? It is certainly not a prominent characteristic of Judaism, nor is it especially apparent to outsiders.

An Internal Midrash-like Reference

Therefore, it seems that the importance of the choice of this unique communal name was intended more for the Jewish community than for the Chinese, and as such, uses a kind of insider reference. Only someone familiar with the Torah would make this connection. Thus, the Jews decided, in a uniquely Jewish way, to distinguish themselves from the Muslims by playing off a story in their Torah.[17]

The prohibition against eating the gid hannasheh, and the requirement for a specialist to remove it to render this part of the meat kosher, was meticulously observed by all Jewish communities. It had far-flung influence on Jewish naming patterns, regarding personal names, nicknames, and family names. In the case of the Kaifeng Jewish community, this extended even to their communal name, inspired by the fact that this story marks the moment when the name “Israel” was created.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 10, 2025

|

Last Updated

December 27, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Aaron Demsky is Professor (emeritus) of Biblical History at The Israel and Golda Koschitsky Department of Jewish History and Contemporary Jewry, Bar Ilan University. He is also the founder and director of The Project for the Study of Jewish Names. Demsky received the Bialik Prize (2014) for his book, Literacy in Ancient Israel.

Essays on Related Topics: