Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Ancient Mapping: Israelite Versus Egyptian Orientation

Reproduction of the 6th c. C.E. Madaba Map discovered in Saint George Church in Madaba, Jordan. Credit: Bernard Gagnon / Wikimedia.

Qādîm Wind

The term “qādîm wind,” literally “forward wind,” appears three times in Exodus, twice in describing the plague of locusts and once in the story of the Israelite escape by the sea:

Locusts

שמות י:יג וַיֵּט מֹשֶׁה אֶת מַטֵּהוּ עַל אֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם וַי־הוָה נִהַג רוּחַ קָדִים בָּאָרֶץ כָּל הַיּוֹם הַהוּא וְכָל הַלָּיְלָה הַבֹּקֶר הָיָה וְרוּחַ הַקָּדִים נָשָׂא אֶת הָאַרְבֶּה.

Exod 10:13 So Moses held out his rod over the land of Egypt, and YHWH drove a qādîm wind over the land all that day, and all that night and when morning came, the qādîm wind had brought the locusts.

Escape by the Sea

שמות יד:כא ...וַיּוֹלֶךְ יְ־הוָה אֶת הַיָּם בְּרוּחַ קָדִים עַזָּה כָּל הַלַּיְלָה וַיָּשֶׂם אֶת הַיָּם לֶחָרָבָה...

Exod 14:21 ...And YHWH drove back the sea with a strong qādîm wind all that night, and turned the sea into dry ground....

The biblical authors use details such as what kind of wind was blowing to make the story vivid and clear to their Israelite readers. In biblical Hebrew, a qādîm wind refers to an eastern wind, but does this make sense in an Egyptian context?

Whence Come Locusts

Locusts are a subset of grasshoppers. In their normal phase (called solitaria), grasshoppers are solitary creatures, but certain species of grasshopper react to overcrowding with a polymorphic shift and nomadic, swarming behavior (this phase is called gregaria). Many species of grasshopper/locust exist throughout the world. The species that infests Egypt and Israel periodically, from ancient through modern times, is called the “desert locust” or Schistocerca gregaria and they originate in the south of Egypt, in the area of modern Sudan. Thus, they come up from the south.

And yet, in Exodus 10, YHWH makes use of the qādîm (i.e., eastern) wind to bring up the locusts. This would imply that the locusts came from the Red Sea or the Arabian Peninsula, but this is not an accurate depiction of locust infestations in Egypt. Shadal (R. Samuel David Luzzatto, 1800-1865) already noted this problem:

אם היתה רוח מזרחית בא הארבה מארץ ערב, אמנם הארבה מצוי יותר בארץ כוש, ולפי זה היה צריך שיהיה הרוח רוח תימן.

If this was an east wind, then the locusts came from the Arabian Peninsula. However, locusts are more frequently found in Kush (Sudan and Ethiopia), but then, it should have been a southern wind (teman).

This problem has been recognized and resolved in a variety of ways.

1. Ignorance

It is possible that the biblical author(s) knew that Egypt suffers from locust swarms but did not know where these locusts came from. But had the Israelite author projected his own reality onto an Egyptian context, he should have said that the locusts were blown in from the south (רוח תימן), as was the case in Israel. East is a strange choice here, as it is neither the direction from which locusts come to Israel or Egypt.

2. A Powerful Wind

In his gloss on 10:13, William Propp suggests:

Perhaps rûaḥ qādîm simply connotes a mighty wind from any direction.[1]

In keeping with this, Propp translates literally “forward wind.” He further suggests in his gloss on 14:21:

This forward wind is among Yahweh’s favored weapons… Hos 13:15 calls it Yahweh’s wind.

This solution doesn’t work for this story, however because of the invocation of the opposite wind later in the story, i.e., the “sea wind.”

The Sea (Yam) Wind

When YHWH is ready to drive out the locusts from Egypt, he does so by bringing the opposite of a qādîm wind. (Exod 10:19).

שמות י:יט וַיַּהֲפֹךְ יְ־הוָה רוּחַ יָם חָזָק מְאֹד וַיִּשָּׂא אֶת הָאַרְבֶּה וַיִּתְקָעֵהוּ יָמָּה סּוּף.

Exod 10:19 YHWH caused a shift to a very strong yam wind, which lifted the locusts and hurled them into the Suph Sea.

In biblical Hebrew, the “yam” or “sea wind” is the name for the western wind, since the Mediterranean Sea is to the west of Israel. Here it is the opposite of the qādîm wind, implying that the story has an east-west dichotomy here, and that qādîm wind cannot simply mean “strong wind from any direction.” This was already noted by Shadal in his gloss on Exod 10:13, who also thought of the possibility that qādîm could be a general term for any wind, but discarded it:

ואין לומר כי קדים תאר לרוח עזה מאיזה צד שתבוא, כי למטה מפורש כי רוח ים היה הפך הרוח הזה.

It cannot be suggested that qādîm is being used here to describe a strong wind irrespective of the direction from which it comes, since below the verse says explicitly that a sea wind comes from the opposite side of this wind.

3. Qādîm as South

The LXX translates the phrase qādîm wind as south wind (ἄνεμον νότον). Shadal quotes Samuel Butchart (1599-1677) in defense of this translation. Moreover, Shadal notes that Ernst Rosenmüller (1768-1835) supports the translation of qādîm as south (or southeast) by noting that in Psalm 78:26, concerning the quail, qādîm is parallel to teman (south) wind:

יַסַּע קָדִים בַּשָּׁמָיִם וַיְנַהֵג בְּעֻזּוֹ תֵימָן.

He set the east wind moving in heaven, and drove the south wind by His might.

The parallelism here, however, is not necessarily evidence that teman and qādîm are synonymous; the verse may simply be using two different winds poetically. Insofar as the translation of qādîm as south, Propp suggests that the LXX translation is based on the Alexandrian translators’ knowledge of where locusts came from.

4. God Can Do Miracles

Finding the standard answers unsatisfactory, Shadal suggests that qādîm here means “east,” and that bringing quail from the east was a miracle:

ולפיכך אין לדחוק ולומר שבא הארבה מארץ כוש, כי לא יבצר מה' להביאו מארץ ערב.

Thus, we should not make convoluted arguments to [translate the verse in such a way] so that the locusts come from the land of Kush, for it is not beyond God’s capacity to bring them from Arabia.

In short, if God can turn the Nile to blood, God can bring locusts from Arabia. This seems more like capitulation than an answer.

Answer 1

Directions from an Egyptian Perspective

One possible answer to this problem comes from the difference between the way Egyptians oriented themselves in the world and the way Israelites did. To understand the point clearly, it is first useful to think about how we, as moderns, orient ourselves.

For hundreds of years, our maps have always used north as an orientation point. This has to do with the invention of the compass. Although invented in 200 BCE China, compasses only began to appear in Europe in the 13th -14th centuries. Compasses always point north, and thus we orient all maps and globes in relation to the north, which is “up” on a two dimensional plane. This is simply a convention; north is not actually “up” any more than south, east, or west. In fact, the ancients did not use north to orient themselves.

Israelite Orientation: Toward the Sun (East)

The Israelites oriented themselves towards the east. This reflects a solar orientation, since the sun, which plays a central role in ANE religious thinking, rises in the east.[2] In fact, the modern term “orientation” comes from the word “orient” meaning east. The eastern orientation is clear from the Hebrew term for east, qedem (קדם), which also means forward. All other directions derive from this orientation.

Thus, the Hebrew word for “right” ימין also means south, and the Hebrew word for “left” שמאל, also means “north.” The word for “backwards” אחור also means “west,” and thus the Mediterranean Sea is called הים האחרון (Deut 11:24, 34:2), i.e., the western sea or literally, “the sea in the back.” When the prophets (Joel 2:20, Zech 14:8) depict the world from east to west, it is from “the eastern sea” (הים הקדמוני) to “the western sea” (הים האחרון) or literally, “from the sea in the front to the sea in the back.”

Egyptian Orientation: Toward the Source of the Nile (South)

Egypt had a different geographical orientation. The most significant geographical feature for the Egyptians was the Nile, which flows from Sudan in the south to the Mediterranean Sea in the north. It was the source of life for Egypt. It provided fresh water, fertilized the fields and served as a main transportation route, connecting all major settlements.

Egyptians faced upstream to await the coming of Hapi, the Egyptian name for the coming of the Nile silt sent by the Nile god Hapi. Thus, the Egyptian term for south was “face” or “upstream.” “Back,” “downstream,” or “end,” was the term for north. With this orientation towards the south, right and left referred to west and east respectively. In fact, the Egyptian term for “right” is actually cognate with the Hebrew term, (ỉmnt in Egyptian, ymn in Hebrew),[3] although in Egyptian it referred to the west (not the south).

It is possible that the Israelite story-teller, when using the term qādîm, means to express this concept from the perspective of the Egyptians. A “forward wind” in Egypt would, in fact, be a south wind, and a sea wind would be a north wind.[4] This could also explain why the Alexandrian authors of the LXX translated qādîm as south; they were thinking like Egyptians.

This solution, which assumes that the Israelite author of the locust episode was intimately familiar with Egyptian norms and would even use them as his reference point in writing his story, is possible, but not fully convincing. Thus, I suggest another possibility.

Answer 2

Ancient Maps: Egypt in the South

We live in a world with globes and satellite photographs. Our understanding of the relative sizes, distances, and positioning of land masses has been fine-tuned by modern cartography and the ability to take pictures from space and make exact measurements. In the ancient world, however, the understanding of the size and position of countries relative to each other was vague and imprecise.

Geographically speaking, the traveler from Israel to Egypt journeyed south and then west. Such a traveler would have followed the ancient road called the way of Horus that led from Ashkelon straight to Egypt along the coast. Those travelling this road would have watched where the sun appeared, and would know the approximate direction they were travelling. Nevertheless, most ancients did not undertake this journey, and many Israelites were sure that Egypt was situated directly south of Israel.

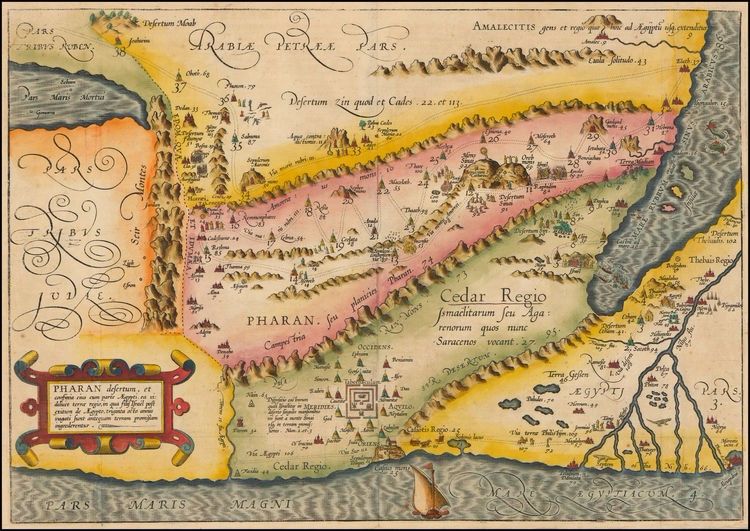

This misconception is seen even in later maps. For example, the Madaba map was drawn in ca. 6th cent C.E., and is found as part of an ancient mosaic floor in St. George Church in the city of Madaba, Jordan. Another, much later map is the Situs Terræ Promissionis, drawn by Christian van Adrichom, in Amsterdam, in 1590 C.E.! In these maps, Egypt is situated south of Israel and the Nile flows into the Mediterranean from the east westwards. In these maps, the Nile River and the Red Sea are perpendicular to the Jordan River and Dead Sea.

In this conception, Egypt’s "south" would be the same as Israel’s east, thus qādîm (forward) would have been the correct term in any event.[5] A geographic conception such as this might also explain why the Alexandrian translators used “south” for qādîm in the LXX; the two would have been synonymous.

Blowing Back the Sea

These explanations also help solve the problem of the qādîm wind during the Israelite’s escape from Egypt. The Israelites flee Egypt to the Sinai Peninsula on their way to Canaan; geographically speaking this is from west to east. The eastern Egyptian frontier is dotted with a row of lakes that were connected by manmade canals and it formed a barrier between Sinai and Egypt.[6] The lakes and canals were abounded with crocodiles.[7] One of these lakes is the biblical Yam Suph (Sea of Rushes). In order for the Israelites to get to Sinai, they need to cross this water.

According to the biblical account, when the Israelites arrive at this row of lakes and canals, the wind blows the water back so that they can move forward.[8] In order to accomplish this, God uses a qādîm wind:

שמות יד:כא ...וַיּוֹלֶךְ יְ־הוָה אֶת הַיָּם בְּרוּחַ קָדִים עַזָּה כָּל הַלַּיְלָה וַיָּשֶׂם אֶת הַיָּם לֶחָרָבָה...

Exod 14:21 ...And YHWH drove back the sea with a strong qādîm wind all that night, and turned the sea into dry ground...

Logistically speaking, a southern wind would have been needed to push the water northward, thus drying the southern side of whichever lake they were camped near and producing dry ground for the Israelites to traverse.[9] An eastern wind would have accomplished nothing but to push the water into the Israelite camp standing on the coast.

It is thus possible that here too, the text is using an Egyptian frontal orientation and the qādîm wind means “southern” rather than “eastern” wind. Alternatively, the author may have had envisioned Egypt as directly south of Israel, with the Israelites escaping north to Sinai, and thus an eastern wind would have done the job.

Whichever solution is preferred, it is necessary to take into account ancient conceptions of geography to make sense of an otherwise inexplicable detail in these two biblical stories.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 13, 2017

|

Last Updated

February 4, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. David Ben-Gad HaCohen (Dudu Cohen) has a Ph.D. in Hebrew Bible from the Hebrew University. His dissertation is titled, Kadesh in the Pentateuchal Narratives, and deals with issues of biblical criticism and historical geography. Dudu has been a licensed Israeli guide since 1972. He conducts tours in Israel as well as Jordan.

Essays on Related Topics: