Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Composing the Song of Deborah: Empirical Models

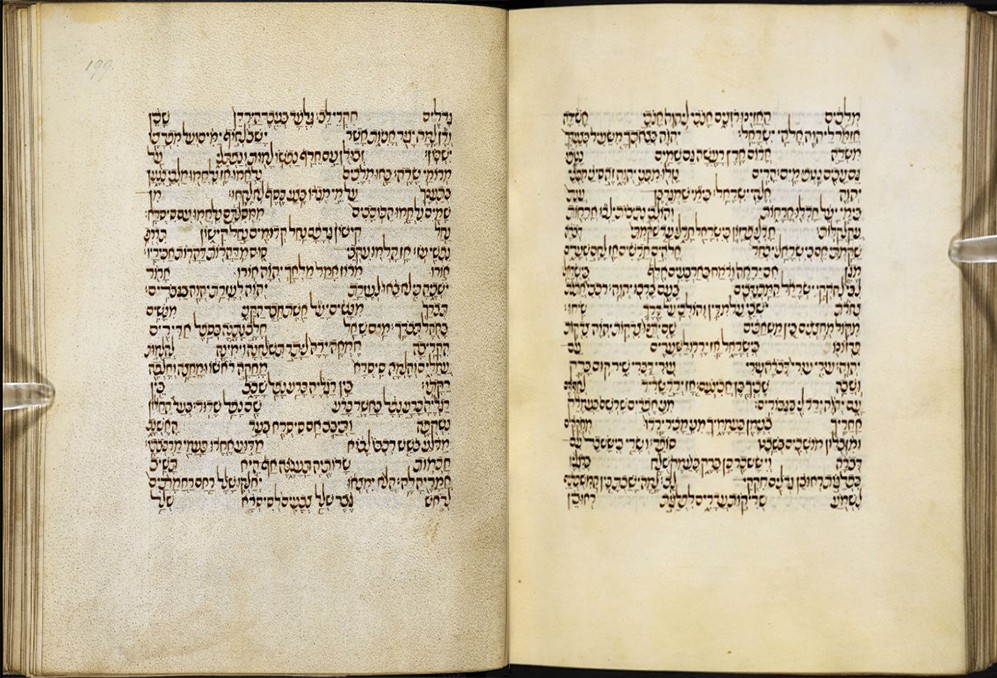

Song of Deborah, late 15th c., MS 15283, ff. 198v-199r. British Library

The Hebrew Bible contains only two narrative battle poems: The Song of the Sea (Exodus 15) and the Song of Deborah (Judges 5). Other poems celebrate military victories (2 Samuel 22, for example), but no others that tell the stories of the battles.[1] These two songs, however, differ in a fundamental way: the Song of the Sea focuses on God alone, the Song of Deborah focuses on human events. Here I focus on the Song of Deborah.

Most modern scholars consider the Song of the Sea and the Song of Deborah among the oldest parts of the Hebrew Bible.[2] The early date for the Song of Deborah is based in large part on matters of language,[3] but certain details mentioned in the song also point in this direction:

- The village militias, פְרָזוֹן (v. 7) contrast with the standing armies of the tenth century;

- The practice of בִּפְרֹעַ פְּרָעוֹת בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל (v. 2), which may refer to a practice of growing hair long before battle, is found only here and in the ancient poem of Deut 32:42 (מֵרֹאשׁ פַּרְעוֹת אוֹיֵב);[4]

- The structure of the tribal system seems to fit the Iron I period rather than anything later: in the absence of a monarchy, Deborah relies on the tribes coming to mutual defense—and then laments their failure to do so;

- The economic picture of the poem suggests a lack of any centralized authority or economic system.[5]

As modern readers, we want to understand every text in its various contexts. We just touched on its likely historical context, but that is not sufficient. We might also ask: What is the literary context of the Song of Deborah? How does it function in the Book of Judges, and how does it contribute to the structure of the book or the development of its literary themes? Finally, we can explore its generic context, asking: What kind of text is this?

We determine the song’s genre by asking what other biblical texts are similar to it, and thus relevant for an understanding of the song, as well as exploring similar extra-biblical texts. Such comparisons can also help us answer related questions such as: How was this song written? Why do people write such songs? Was it performed, and if so, how? We can begin to answer such questions by looking at parallels in other cultures that may provide empirical models for biblical studies.

Empirical Models

In the last few decades, modern biblical scholars have used empirical models for various parts of the Bible[6] to help explain how and why these texts were written, and how they were “published” and circulated. Two very different empirical models, one using oral Arabic poetry, the other from ancient Egyptian royal battle poems, overlap with the Song of Deborah and suggest different ways of understanding how it was composed and by whom.[7]

Bedouin and Pre-Islamic Arabic Poetry

Oral Arabic poetry is known to us from diverse collections. The poems most similar to the Song of Deborah are called qaṣīdā poems, an old and venerable genre. The qaṣīdā (often translated “ode”) is a poem of dozens of lines which rhymes throughout and typically addresses one theme in some detail; the Bedouin call it a “serious” poem.[8]

While we only have qaṣīdā poems dating back 1500 years, pre-Islamic Arabic poetry has been fruitfully compared to contemporary poems current among non-literate Arabs.[9] This genre has remained stable, making it likely that the same style of composition was in use even 1500 years before that! Military-themed qaṣīdā poems overlap significantly with Deborah’s Song.

The celebration of military victories is one of the primary roles of the known Arabic poems of recent centuries,[10] and the same was true of Arabic poetry in Islamic times. Perhaps the best-known examples are the 9th-century poem by Abū-Tammām[11] and the 10th-century poem of Al-Mutanabbi,[12] both celebrating victories over the Byzantines. Both not only laud the victors, but also mock the defeated Byzantine emperors.[13]

The motif of taunting the enemy, using imaginary scenes of disgrace after defeat, is also found in much of the more recent poetry. For example, an anonymous Tiyāhā poem (the Tiyāhā are a major Bedouin tribe in the Sinai and Negev), a poem of relief after victory,[14] concludes:

How many mounts have their painful fate met,

Which must now be replaced from the horse broker’s stock!

How many fair dames will spend sleepless nights,

Complaining of the widowhood that has orphaned their young!

The comparison to the taunt of imagining Sisera’s mother anguished at the window (Judg 5:28) is tantalizing.

בְּעַד הַחַלּוֹן נִשְׁקְפָה

וַתְּיַבֵּב אֵם סִיסְרָא בְּעַד הָאֶשְׁנָב

מַדּוּעַ בֹּשֵׁשׁ רִכְבּוֹ לָבוֹא

מַדּוּעַ אֶחֱרוּ פַּעֲמֵי מַרְכְּבוֹתָיו.

Through the window she watched,

The mother of Sisera moaned through the lattice,

“Why does his chariot tarry in arriving?

Why so late are the hoofbeats of his horses?”

This tactic of imaginatively describing women lamenting the non-return of a warrior is found in much earlier Arabic poetry, as well. A poem ascribed to the famous warrior-poet ʿAntarah ibn Shaddād (6th century Arabia) ends:

I felled him, that champion

Amid rusty armor and severed heads.

The vultures waited on him

like maids attending a bride.

That night his women

Caught between shock and grief

Prepared his corpse for the soil.[15]

The Composition of Qaṣīda Poems

The scholar of Bedouin studies Clinton Bailey recorded and published many Bedouin poems from the Negev. He describes the composition and transmission of a qaṣīdā thus: Following some important event in a person’s life, the poet composes the qaṣīda alone or with a friend, and thus has a chance to choose his phrases carefully.[16] For example, one poet reported:

I sat with my little pot-stove from the felucca and drank tea. When I had drunk tea, I thought quietly to myself, for perhaps two or three hours, remembering what had happened. I gathered up words from here and there and pressed them together, and I composed the poem. Some people saw me sitting there reciting slowly, saying the words softly. They said, “What have you composed, Jum‘a? Certainly you must have made yourself a poem while drowning at sea.” I said: “Yes, I have made a poem.” They said: “Give us knowledge of the poem.” And I recited this poem…

When the author recites a poem, others may memorize it, allowing it to circulate more broadly. The composition of qaṣīdā poetry offers a useful empirical model for considering the Song of Deborah. Here we have a poem composed near the time of an event by a local bard or poet, which circulates orally, and is committed to memory.

Historical Background Information

Qaṣīdas often open with a narrative introduction, in which the reciter explains the background of a poem before reciting the poem itself. The poem proper does not always repeat details of this introduction, which, unlike the poem, is often not memorized, and sometimes not remembered at all.

Moreover, sometimes new historical introductions, unrelated to the poem’s actual composition, get attached to the poem. For instance, Bailey reports that he once heard a poem introduced with a story relating to the 1960s. Unbeknownst to the reciter, but known to Bailey, the story could not have been original to the poem or set in the 1960s, since the poem had been published in 1928 by Czech Orientalist Alois Musil in The Manners and Customs of the Rwala Bedouins.

The inclusion of a historical introduction which may or may not accurately reflect the real details of the episode that gave rise to the poem is highly reminiscent of the presentation of Deborah’s Song in Judges 5, which follows a prose account in Judges 4 that many scholars suggest tells a slightly different story than what is conveyed in the poetry.[17]

Could the Song of Deborah be a military themed qaṣīdā-style poem, composed by an Israelite bard in commemoration of some event or events and circulated orally? Yes, but an entirely separate set of texts, also comparable to the Song of Deborah, suggest a very different model for understanding the biblical poem and its composition history.

Ramesside Poems

Two Egyptian poems from the thirteenth century B.C.E., Ramesses II’s commemorations of his battle at Qadesh and the battle hymn of his son Merenptah, are reminiscent of the Song of Deborah.

Battle of Qadesh

In his fifth regnal year, 1274 B.C.E., Ramesses II fought a massive and momentous battle against the Hittites near Qadesh, on the Orontes—a march of more than 400 miles from Ramesses’ capital at Pi-Ramesses. The battle was fought to a draw, but Ramesses saw it as a great personal victory, since at one point defeat seemed certain, and the Pharaoh himself was able to turn the course of the battle and maintain Egypt’s position (or so he claimed).

To commemorate the events, Ramesses II commissioned two versions of the story, both of which appear on temples around Egypt. One of these compositions is an epic poem that tells the story of the events at Qadesh. As the late Egyptologist Miriam Lichtheim[18] pointed out, this epic poem was a new kind of poem in the history of Egyptian literature.

A few highlights of the poem are particularly striking in connection with the Song of Deborah:

- It begins with a poem in praise of the might of Pharaoh when he steps out:

His majesty was a youthful lord,

active and without his like,

his arms mighty, his heart stout,

his strength like Mont in his hour,

of perfect form like Atum,

hailed when his beauty is seen.

The Song of Deborah begins with a similar poem in praise of God as he steps out:

שופטים ה:ד יְ־הוָה בְּצֵאתְךָ מִשֵּׂעִיר

בְּצַעְדְּךָ מִשְּׂדֵה אֱדוֹם

אֶרֶץ רָעָשָׁה גַּם שָׁמַיִם נָטָפוּ

גַּם עָבִים נָטְפוּ מָיִם.

ה:ה הָרִים נָזְלוּ מִפְּנֵי יְ־הוָה זֶה סִינַי

מִפְּנֵי יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.

Judg 5:4 O YHWH, when you went out from Se‘ir

when you stepped forth from the field of Edom

the earth quaked, even the heavens dripped,

yes, the clouds dripped water

5:5 the mountains flowed before the Lord of Sinai

before YHWH, God of Israel.

- Both Ramesses’ poem and the Song of Deborah open the narrative of the battle by emphasizing the lack of military support in the hand of the hero. For Ramesses, “no officer was with me, no charioteer / no soldier of the army, no shield-bearer,” and for Deborah (v. 8), מָגֵן אִם יֵרָאֶה וָרֹמַח בְּאַרְבָּעִים אֶלֶף בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל “Was any shield to be seen / any spear, in the forty thousand of Israel?”

- Ramesses gives credit to Amun for the victory despite the king’s lack of military might, allowing him to be victorious. The Song of Deborah gives credit to the supernatural forces, הַכּוֹכָבִים מִמְּסִלּוֹתָם “the stars from their courses”(v. 20) that fought for Israel.

One copy of this Poem (P. Sallier 3) ends with a colophon stating that the text was written in year 9—in other words, 4 years after the battle itself. Clearly, the authors were the best poet-scribes that the royal court could find, and the text was published by being prominently inscribed on temple walls as far south as Sudan. In fact, the poem was well-enough known that it is not implausible that some Israelites might have known it.[19]

If Ramesses II’s Qadesh poem is the first epic poem in Egyptian literature, the second one followed soon. Merenptah’s “victory stele” is well-known to biblicists and historians because it is the first time that Israel is mentioned in a text. Again, the stele presents a poetic account of a battle recounted elsewhere in prose, although here the prose is much longer, and the two are not found side-by-side.[20]

The stele is primarily a laudatory text, which concludes with a poem of encomium. Its topic is a battle against a combined Libyan-Sea Peoples force, and this battle is narrated in a number of the king’s inscriptions, in Karnak and elsewhere.

Two specific comparisons to the Song of Deborah jump out.

- First, Merenptah’s stele focuses on travel being possible once again thanks to his victory, since the roads were no longer treacherous:

Great joy has arisen in Egypt,

Shouts go up from Egypt’s towns;

They relate the Libyan victories

Of Merneptah, Content with Maat (social order)[21]:…

One walks free-striding on the road,

For there is no fear in people’s hearts;

Fortresses are left to themselves,

Wells are open for the messengers’ use.

Bastioned ramparts are becalmed,

Sunlight only wakes the watchmen.

The same motif frames the victory in the Song of Deborah (Judg 5:6–7):

בִּימֵי שַׁמְגַּר בֶּן עֲנָת בִּימֵי יָעֵל

חָדְלוּ אֳרָחוֹת

וְהֹלְכֵי נְתִיבוֹת יֵלְכוּ אֳרָחוֹת עֲקַלְקַלּוֹת.

חָדְלוּ פְרָזוֹן בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל חָדֵלּוּ

עַד שַׁקַּמְתִּי דְּבוֹרָה

שַׁקַּמְתִּי אֵם בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל.

In the days of Shamgar ben ‘Anat, in the days of Ya‘el,

Caravans ceased,

Road travelers traveled roundabout routes.

Open travel ceased, entirely ceased,

Until you rose,[22] Deborah,

You rose, O mother in Israel!

- Both texts imaginatively relish the aftermath of the defeat of the enemy hero back in his hometown. Merenptah focuses on “the vile chief, the Libyan foe,” Merey, and especially on the reaction of his townspeople back in Libya:

The vile chief, the Libyan foe,

Fled in the deep of night alone,

No plume on his head, his feet unshod,

His wives were carried off from his presence,

His food supplies were snatched away,

He had no water to sustain him.

The gaze of his brothers was fierce to slay him,

His officers fought among each other,

Their tents were fired, burnt to ashes,

All his goods were food for the troops.

When he reached his country he was in mourning,

Those left in his land were loath to receive him,

“A chief, ill-fated, evil-plumed,”

All said of him, those of his town.

The Song of Deborah also focused on the defeated hero’s home. As Sisera’s mother looks out the window, wondering why her son hasn’t returned, her advisers try to encourage her (Judg 5:29–30):

חַכְמוֹת שָׂרוֹתֶיהָ תַּעֲנֶינָּה

אַף הִיא תָּשִׁיב אֲמָרֶיהָ לָהּ.

הֲלֹא יִמְצְאוּ יְחַלְּקוּ שָׁלָל

רַחַם רַחֲמָתַיִם לְרֹאשׁ גֶּבֶר

שְׁלַל צְבָעִים לְסִיסְרָא

שְׁלַל צְבָעִים רִקְמָה

צֶבַע רִקְמָתַיִם לְצַוְּארֵי שָׁלָל.

The wise among her advisers answer her,

Even she responds to her own sayings:

“Surely they are finding and dividing spoils,

A girl, two girls for each warrior,

Spoils of dyed cloth for Sisera,

Spoils of dyed cloth embroidered,

Dye of many cloths for the necks of spoils.”

In both cases, which are quite poignant and evocative, the scene is entirely imagined.[23]

Although it is possible that Israelite scribes would have been aware of Ramesses and Merenptah’s poems, the main point here is that during the thirteenth century B.C.E., the Egyptian kings used a genre of poetry that was fundamentally narrative, using poetic tactics to compose panegyrics to the king after battles, and that not long after, Israel composes a poem in this same style. This may suggest that the Song of Deborah, like Ramesses and Merenptah’s poems, was an official composition by recognized poets and promulgated through official channels.[24]

Implications of These Empirical Models

We have, then, an embarrassment of riches. More often, biblicists searching for empirical models for their theories of textual development are hard pressed to find anything. But here we have two empirical models with clear parallels to the biblical Song of Deborah, and both are well attested and fairly well understood.

If we focus on Arabic oral poetry as an empirical model, we can well imagine a poem composed shortly after the event—even within a few days or weeks. This poem would then have circulated orally among reciters in ancient Israel, perhaps with certain changes, additions, or deletions creeping in over time.

Scholars of oral poetry claim that there is a statute of limitations on how long a poem may remain in oral circulation: “studies in other cultures would seem to indicate that two hundred years is the absolute maximum of time for a piece of oral poetry to remain in men’s memories, even this being highly unusual.”[25] If so, the poem was written down within two centuries of the events that it describes. This model also provides an empirical basis for the hypothesis of the poem spawning the prose account.

The Egyptian comparisons, on the other hand, would suggest a very different mode of composition and transmission – more centralized, authoritative, and literary. And each model would have different implications for how we read the Song of Deborah—since an account recorded by an epic poet who was an eyewitness is different from a royal epic poem written in the palace.

Both models have much to commend them, and both are helpful for thinking about the Song of Deborah in its ancient context. It is difficult to choose one over the other until more work is completed to articulate exactly how each can or cannot shed light on this enigmatic biblical text.

_________________

For Shira Devora

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 5, 2020

|

Last Updated

February 8, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Aaron Koller is professor of Near Eastern studies at Yeshiva University, where he is chair of the Beren Department of Jewish Studies. His last book was Esther in Ancient Jewish Thought (Cambridge University Press), and his next is Unbinding Isaac: The Akedah in Jewish Thought (forthcoming from JPS/University of Nebraska Press in 2020); he is also the author of numerous studies in Semitic philology. Aaron has served as a visiting professor at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and held research fellowships at the Albright Institute for Archaeological Research and the Hartman Institute. He lives in Queens, NY with his wife, Shira Hecht-Koller, and their children.

Essays on Related Topics: