Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Esther, Queen of the Conversas

Ahasuerus and Esther Reigning as King and Queen; Tapestry Series Esther and Ahasuerus (Panel III), 1490, Museum de la Seo, Zaragoza, Spain.

Like so many Jewish girls, at age eight I dressed up as Queen Esther for Purim. Beautiful and heroic, she was the obvious choice, just edging out the Hamantaschen outfit I was sporting the year before. Even at that young age, thanks to our Sunday morning classes, we all knew that she saved the Jewish people. Who wouldn’t want to be like Esther?

Conversos in Spain

Esther was the most beloved biblical figure amongst conversos or crypto-Jews, a community created when Iberian Jewish life transformed dramatically between the first mass baptisms in Spain in 1391 and the subsequent exile from Spain in 1492 (and from Portugal in 1497). Before this time, Jews lived openly alongside Muslims and Christians.

Although Jews did face discrimination earlier than this in the Iberian Peninsula, 1391 was the first time that a pogrom was waged against them and Jews were converted en masse against their will.[1] Families became divided along religious lines with the newly converted either secretly maintaining Jewish practice (crypto-Jews) or taking on a full Catholic identity.

Even though the year 1391 changed the way families and communities were configured throughout Spain, many elements of Jewish tradition continued to shape Iberian life in the Peninsula and the New World. The expulsion of non-converted Jews in 1492 removed the last vestiges of openly practiced Judaism from Spain, and greatly shaped the Sephardic Diaspora, as Sephardic Jews relocated throughout the globe.

In 1478, 14 years before the expulsion of the Jews, Spain established an Inquisition under a Dominican friar named Tomás de Torquemada, the first Grand Inquisitor. The goal of the Inquisition was to weed out heretics from among the faithful, especially secret Jews from among the converted.[2] Anyone in Spanish territory—whether in Iberia itself or in the New World—believed to be secretly practicing Judaism would be condemned as a heretic and punished publicly in an auto-da-fé (literally “act of faith”).

The specific punishment of a condemned apostate in an auto-da-fé varied, but they all began with the apostates being paraded through a central square visible to the citizenry. Some received relatively light sentences, such as being shamed by wearing a sackcloth, while others would receive the most extreme form of punishment, namely burning at the stake.[3]

The Carvajal Family

The crypto-Jewish Carvajal family faced persecution by the Inquisition on not one but two occasions. This family of Spanish descent relocated from Portugal to New Spain (today Mexico) in 1569 seeking more religious freedoms.

Although official policy mandated that people of converso descent not be allowed to travel to the New World, the whole family including the matriarch, Francisca, and her children, Isabel, Luis, Leonor, Mariana, and Catalina, were brought over through the help of their uncle, Luis de Carvajal the elder, who was governor of New Leon. There that they faced both Inquisition trials in 1589 and 1595–1596.

The Carvajal family holds a prominent place in the studies of the crypto-Jewish tradition in the Iberian world. Luis de Carvajal, who called himself a martyr in his second inquisitorial trial and penned an autobiography in prison, has received the most attention.[4] Here, however, I wish to focus on his two sisters, Isabel and Leonor, who were imprisoned twice by the inquisition and ultimately killed after their second trial in 1595–1596 in an auto-da-fé.

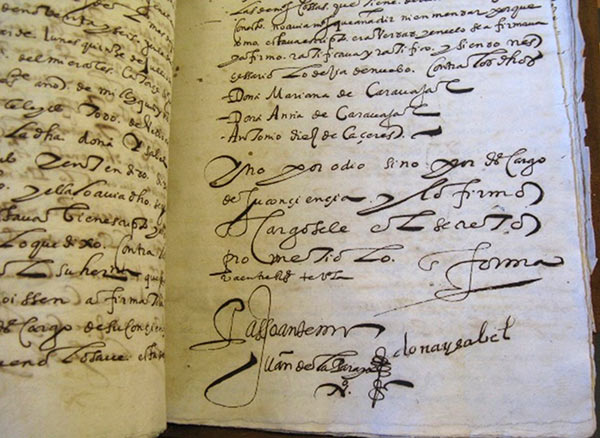

The trial documents leading up to this execution detail the religious practice of the Carvajal sisters, it also details the torture they were subjected to and how they acted while imprisoned.[5] Incredibly, while held in jail cells, they would pass notes back and forth to each other on what they had accessible, such as banana peels and avocado skins.[6]

The Story of the Carvajal Sisters

Isabel de Carvajal was born in Portugal and, like other children in the family, was instructed in their converso background only at the age of bar/bat-mitzvah or slightly later, so that she would know how to keep it secret. Almost all the members of the family embraced the crypto-Jewish practices which the matriarch Francisca shared with her children. One of the sons even entered the clergy since having a family-member in the church made them less likely to be suspected as crypto-Jews. (This was common in crypto-Jewish families.)

After she married another devout crypto-Jew, Gabriel de Herrera, Isabel received further instructions (since there were so many gaps to fill) regarding crypto-Jewish practices from her devout husband, but he died early on, after which, she moved with her family to the New World.

In New Spain, she took turns living with her mother, and with her sister Leonor and her family, who also moved to New Spain. Leonor’s husband, Jorge de Almeida, was also from a converso background, but was often absent due to his career as merchant in long distance trade. As a childless widow, Isabel was able to live in a way that was dedicated to her faith and also took on the additional role as teacher to the younger children in her family.

Studying these sisters reveals much about the nature of crypto-Judaism in New Spain, especially how female practice took a central role in shaping and preserving their religious identity. These women held together the far-flung crypto-Jewish community of the early modern Sephardic Diaspora while the men like Leonor’s husband were actively engaged in trade along routes that connected Spain, Amsterdam, Italy, Angola, and the New World.[7]

With one husband deceased and the other constantly travelling, Isabel and Leonor were the central purveyors of the crypto-Jewish faith in their family and within their crypto-Jewish community of colonial New Spain. They maintained religious practices in the home and taught prayers and songs in Spanish and Hebrew to family members and to others within their crypto-Jewish community.[8]

Whereas Judaism is a patriarchal religion, crypto-Judaism was matriarchal.[9] As stated, men were often absent conducting business for long periods of time and consequently the only people entrusted with conveying religious beliefs to the next generation were women. The opportunities for female-led practice within the Inquisitorial environment shaped the sisters fervent Judaizing.[10]

Esther’s Secret Judaism: Negotiating a Hybrid Identity

Esther was a figure who passed within the majority society in biblical Persia, ultimately revealing her faith to save her Jewish people. This story of hidden religious identity became a huge source of inspiration for crypto-Jews throughout the Sephardic Diaspora, who themselves were passing as Catholics while privately living as Jews.

For the Carvajal women, Esther was a female savior, a resistance figure who risked her own personal safety for the good of the Jewish people.[11] There are many connections between the story of Esther and the reality of Isabel and Leonor’s lives: all three women; Esther and the Carvajal sisters lived double lives; and they passed as members of dominant culture—Persia and New Spain respectively—while living secretly as practicing Jews.

In the book of Esther, Mordechai instructs Esther to not reveal her Jewish origins when arriving at the court (Esth 2:10). Like other crypto-Jews, the Carvajal sisters would have been familiar with this story from the fourteenth-century Biblia Ladinada, composed in the vernacular and written in Latin letters:

non rreconto Ester su pueblo e su generaçion que Mordecai mando a ella que non lo rrecontase.[12]

As instructed by Mordechai, Esther did not reveal her people or her lineage (my translation).

This message of secrecy in this passage parallels the necessary secrecy that crypto-Jews maintained within their communities and daily lives. The Carvajal women took great measures to hide their true religiosity from others, including their household members including non-Jewish servants, and even took many precautions before revealing their identity to other potential crypto-Jews.

Evidence from the Trial

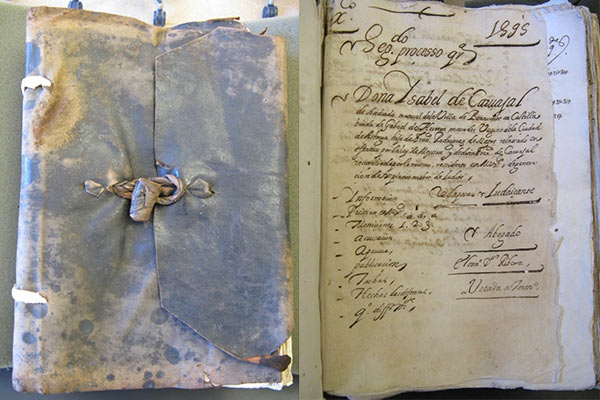

Just as Esther passed herself off as a typical Persian while keeping her religious identity secret, we read in Isabel’s trial how these sisters lived a double-life. The trial document is the official record of the Holy Office and was recorded by Inquisitorial scribes; it somehow survived in its entirety from the Mexican Inquisition over four-hundred years ago… except for the odd worm hole.

Isabel’s full testimony including the questions and responses posed by the inquisitors. Evidence from the trials of other crypto-Judaizers in her community are included within this leather-bound book composed of over four-hundred pages of hand-written text.

The Carvajal women would attend church on a regular basis to feign allegiance to the Catholic Spanish rule:

…after she turned to the Law of Moses, away from Spaniard’s Law of Christ. [The crypto-Jews] had taken the sacraments of the Mother Church without any feeling. And although she didn’t make fun of them she confessed that she took communion, she did so only to obey the rules, because she did not believe that Jesus Christ was their author [of the sacraments], nor did she believe him to be God. (MSS 95/96 v. 4, 334v).[13]

They were public Christians and private Jews, and negotiated these two identities within their home.

There was an altar in the main living room of the house that had some images that she used to trick those who entered. Sometimes, she would kneel in front of the images to make it seem to household that she was Spanish (i.e. Christian). And my mother had a rosary that she would hold in her hands and bring to Mass although she would never pray with it nor would she entrust herself to Jesus Christ nor his blessed mother, but instead it was used to feign [a Christian identity]. (64r-v)

Living in colonial Mexico, the Carvajal women had no choice but to identify themselves as Catholic Spaniards. This identification also allowed them to continue their secret Jewish observance. At the same time, aspects of the Catholic faith, which perfused their daily lives, did modify their Jewish practice. They used ritual-objects such as the rosary and images to hide their crypto-Jewish worship.

Their home became a meeting place for the family as well as other Judaizers in New Spain. It was an important space for crypto-Jewish practice, especially since public places of worship had long been prohibited.

A Patron Saint for Crypto-Judaism

The Cult of Mary within Spain and Latin America was a central element of worship especially for women: Mary was an accessible model who offered comfort and strength in periods of hardship. Like Mary, Esther was a relatable model and heroine for crypto-Jews, who developed a similar type of Jewish Cult of Esther.

Esther became the patron saint of crypto-Judaism. Indeed, the Carvajal women referred to her as Saint Esther “Santa Ester” in their private letters. This fits a practice known elsewhere; in Belmonte, Portugal, for example, the crypto-Jewish community that remained secret until the early twentieth-century, hung pictures of Esther and referred to her as Saint Esther and Holy Queen Esther (Bodian,144).[14]

In calling her Saint Esther, conversos incorporated Christian elements into their practice, again showing how crypto-Judaism is a hybrid faith that cannot be divorced into its constituent Catholic and Jewish influences. Figures such as Esther had power precisely because she had meaning within both faiths.

The Fast of Esther

We see how Esther resonated deeply for Isabel in the following passage:

The said doña Isabel upheld the fast in contemplation of the fast of Queen Esther, in all of the said three days she had not even eaten an egg with ash, and on Saturday doña Isabel only did not fast because it was a holiday (Shabbat), and then she began to fast on Sunday at midday like it is said to continue with her fasting… (229r-v)

As standard in Jewish practice, crypto-Jews observed the Fast of Esther, which falls out on the day before Purim (13th of Adar). But instead of observing it for one day, followed by the celebration of Purim and Shushan Purim, crypto-Jews fasted for three days. Observance of the Fast of Esther among crypto-Jews was important not only in the Carvajal’s community but throughout Spain and New Spain including the island community of Mallorca, and Belmonte Portugal (Gitlitz, 117).

This shift to a three-day fast was likely inspired by Esther’s request of Mordecai and the Jews of Shushan to fast for three days before she meets with Ahasuerus to beg him to spare the Jews (Esth 4:16). The crypto-Jews could not celebrate Purim with a party, so more secretive, interior practices such as the fast of Esther became primary.[15]

On another level, the three-day fast reflects a characteristically Catholic sensibility. Isabel interpreted her crypto-Jewish faith as informed by the penitentiary boundaries of Catholicism. In order to observe the Law of Moses, her body needed to feel a painful connection with her religious practice, and in addition to extended fasts (she fasted throughout the year) she would self-flagellate.

…the said doña Isabel brought a discipline (ciliary) and she would hit herself every day and then fast to observe the said Law of Moses. She confessed that she had not done as much penitence as she wanted due to health concerns, and she promised to not do less than she had promised God. (229r-v)

The penitentiary context, including flagellation and fasting, impacted the Carvajals’ everyday observance of crypto-Judaism. These practices reveal a Catholic context in which they lived their daily lives and contrast with the more overt practices of normative Judaism especially because the Jewish practices preserved in crypto-Judaism were limited to the invisible.

The excessive fasting seems to have been a uniquely female practice.[16] In this way, the body is a female-controlled space that stood out in its defiance of patriarchal Catholic order.

The figure of Esther was transformed by the dire needs of crypto-Jewish women, and we see this in the starkly different way that the Carvajal sisters venerate and imagine her, as compared to normative Judaism. Isabel and Leonor de Carvajal bled for Esther with hair shirts, course garments with bristles that would make the wearer bleed so that they could be physically connected with their faith, they fasted for her, but above all they looked to her for guidance at a time when more and more of their endangered cultural heritage was in their hands.

The Catholic View of Esther

Esther was also a popular figure among Christians in post-expulsion Catholic Iberia in this period, but for very different reasons. In a Catholic context, Esther was far from a transgressive figure who went beyond the boundaries imposed by her gender and religious identity.

As we see in the three-panel tapestry series “Esther and Ahasuerus” (1490), Esther was featured in Catholic Iberia to help construct a narrative of a strong empire in sixteenth-century Spain, at the height of an Imperial Spain and its colonial enterprise.[17] These tapestries retell the Esther story and uphold the idea that she is a pious, loyal and beautiful heroine.

While these images downplay her heroic role as an underdog hiding a Jewish religious identity; they primarily suggest that Esther furthers contemporary gendered norms of female behavior. More specifically, she calls to mind the historical queen Isabella I of Spain (1451–1504), who expelled the Jewish people, and was celebrated for embodying womanly virtues including innocence and piety, while also being a powerful queen. Isabel, as a celebrated queen, helps explain the appeal of the Esther figure for Christians at that time.

Today the series “Esther and Ahasuerus” is displayed in the Museo of La Seo in Zaragoza, Spain. These stunning tapestries, embroidered in gold and silk thread, were hung outside on the walls of the Cathedral every Holy Week (mid-April) for over five-hundred years.

The Christian Holy Week begins the last week of Lent just preceding Easter and celebrates the sacrifices of Christ in the name of humanity. In the early modern period, this Holy week was far more important than Christmas. They were true celebrations that lasted for a full week, when people danced in the streets and enjoyed elaborate parades.

In one image, Esther prepares to go to the king with the help of her courtesans. Instead of the crucial fast of Esther for conversos, here feasting, a main theme of the Esther scroll, is of central importance. It is critical that Esther is featured below Ahasuerus, showing her obedience to the king, an important theme in this tapestry. This moment is revealing because Esther is presented not as a strident protagonist, but instead is demure and clearly inferior, literally a supplicant at his feet (see image above).

This retelling is not about Esther, but instead about the courtly relationship between king and queen, and the majority of visual space in the central panel is given to the king in his redolent splendor. The message is clear, the king is the source of power and she is at his mercy. Far from the strong figure that Isabel could draw comfort from, her passivity is what is highlighted in this context.

The crypto-Jews would have been exposed to this version of Esther, and the Virgin Mary and historical queens such as Isabel the Catholic similarly shaped their religious practice and personal identities. The crypto-Jews are responding to this imagery with an Esther of their own.

Contrasting Esthers in Iberia

Esther is a cultural chameleon who survived by passing herself off as something she was not and triumphed by “coming out.” In this way she seems a more contemporary figure than one would expect. As Esther is recuperated in different places throughout the Sephardic Diaspora, she transgresses geographical boundaries and connects conversos who found themselves in disparate nations.

Crypto-Jews as exemplified by the Carvajal family were mobile and global. They also had multiple loyalties; they were Jewish and Christian, and their practices became hybrid because they lived between two worlds, the new and the old, the Jewish and the Catholic.

Early modern non-Jewish women saw public models of royalty in Queen Isabel of Castile and Catholic models of saints, nuns and the Virgin Mary. Esther was an alternative model for crypto-Jewish women. They aspired to be like their Jewish Queen and heroine, desiring her physical beauty and her interior strength. Like Esther, they aspire to resist adversity, survive and flourish.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 22, 2021

|

Last Updated

February 7, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Emily Colbert Cairns is an Associate Professor of Spanish at Salve Regina University. She graduated with a Ph.D. and M.A. in Spanish Literature from the University of California, Irvine. She is the co-editor of, Confined Women: The Walls of Female Space in Early Modern Spain (Hispanic Issues Online 2020) and the author of Esther in Early Modern Iberia and the Sephardic Diaspora: Queen of the Conversas (Palgrave 2017). Colbert Cairns specializes in gender, converso and crypto-Jewish identity in the early modern period and has published with eHumanista, Chasqui, Cervantes Journal and Hispanófila. She spent the fall of 2019 conducting research in the Archivo de la Diputación de Sevilla in support of her current book project on breastfeeding practices in the early modern period.

Essays on Related Topics: