Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Ezekiel’s Temple Plan Draws on Babylonian Temples

Ruins of the Ezida temple of Borsippa, dedicated to the god Nabu, with the adjacent ziggurat in the background. World Monuments Fund, Google Arts & Culture

Twenty-five years after Ezekiel is taken into exile in Babylonia (573 B.C.E.), he has a vision in which YHWH transports him to Israel:

יחזקאל מ:ב בְּמַרְאוֹת אֱלֹהִים הֱבִיאַנִי אֶל אֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיְנִיחֵנִי אֶל הַר גָּבֹהַּ מְאֹד וְעָלָיו כְּמִבְנֵה עִיר מִנֶּגֶב.

Ezek 40:2 He brought me, in visions of God, to the Land of Israel, and He set me down on a very high mountain on which there seemed to be the outline of a city on the south.[1]

There he meets a strange figure who leads him on a tour of the future temple:

יחזקאל מ:ג וַיָּבֵיא אוֹתִי שָׁמָּה וְהִנֵּה אִישׁ מַרְאֵהוּ כְּמַרְאֵה נְחֹשֶׁת וּפְתִיל פִּשְׁתִּים בְּיָדוֹ וּקְנֵה הַמִּדָּה וְהוּא עֹמֵד בַּשָּׁעַר.

Ezek 40:3 He brought me over to it, and there, standing at the gate, was a man who shone like copper. In his hand were a cord of linen and a measuring rod.

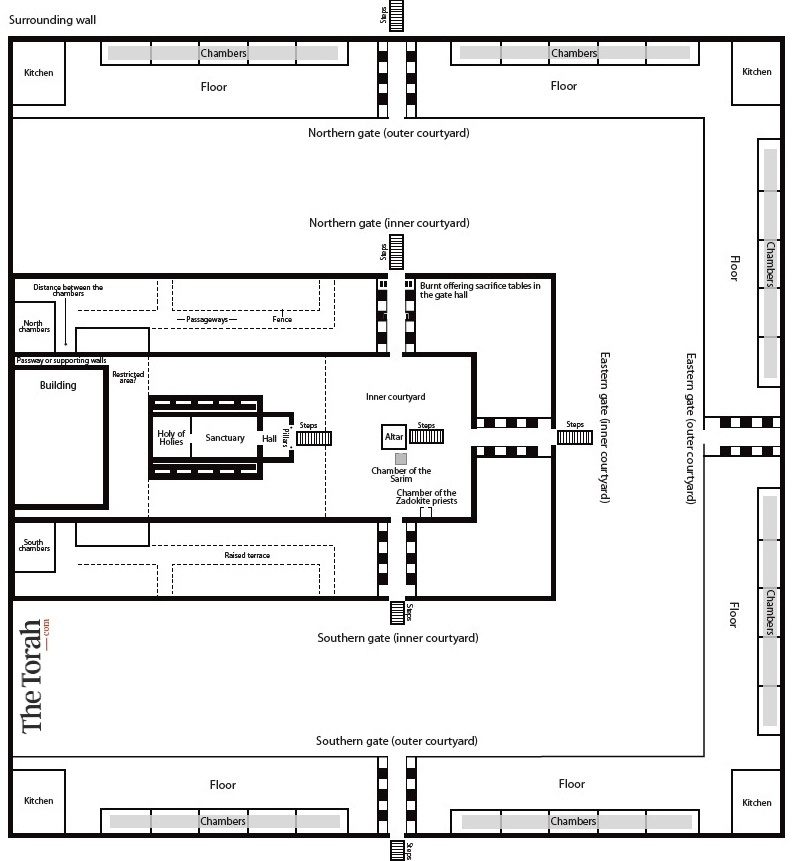

In contrast to the descriptions of the Tabernacle and the Temple of Solomon, Ezekiel’s Temple Vision (chs. 40–48) barely mentions the functions of the parts of the temple itself, instead describing in elaborate detail the measurements of its gates and passages: sixty-three verses are devoted to the gates, courts, and the wall surrounding the temple, while only twenty-six verses are devoted to a description of the structure of the temple.

Ezekiel’s vision begins and ends with the measurement of the חוֹמָה, “wall,” surrounding the entire temple complex (Ezek 40:5, 42:20).[2] The description of Solomon’s Temple does not refer to a wall. The Tabernacle is surrounded by the חֲצַר הַמִּשְׁכָּן, “enclosure of the Tabernacle,” a fabric barrier with a simple gate (Exod 27:9–16; 38:9–20), and is quite different from the wall in Ezekiel’s vision, which is approximately 3 meters in both height and depth (Ezek 40:5).

Three שְׁעָרִים, “gates,” in the wall lead into the area of the temple. The route through them is not completely clear, but it involves ascending flights of מַעֲלוֹת, “stairs,” and passing between תָּאִים, “recesses,” and an אֻלָם, “vestibule” (Ezek 40:6–38). The entrance area also includes an additional space called the אֻלָם הַשַּׁעַר, “vestibule of the gate” (40:39–40, 44:3, 46:2, 8).

In contrast, the detailed description of the Temple of Solomon includes only one verse describing the חָצֵר הַפְּנִימִית, “inner enclosure” (1 Kgs 6:36). The book of Kings contains no mention of gates, nor a description of the means of entry and exit to and from the Temple. It thus lacks any reference to the לְשָׁכוֹת וְרִצְפָה, “chambers and pavement,” mentioned by Ezekiel (Ezek 40:17–18), as well as additional details about the structures situated there (46:21–24).

Ezekiel’s temple has two courts, a חָצֵר הַחִיצוֹנָה, “outer court” (Ezek 40:17), including large chambers intended for sacrifices, and a second, smaller חָצֵר הַפְּנִימִי, “inner (or lower) court” (40:19), where the altar stands (40:47), reached by way of a network of gates and stairs (40:23–44). Finally, the temple structure is divided into three parts: the columned אֻלָם הַבַּיִת, “portico of the temple,” reached by a set of steps (40:48–49); הַהֵיכָל, “the great hall” (41:1–2); and, at the far end of the Temple, the פְּנִימָה, “inner room” called the קֹדֶשׁ הַקֳּדָשִׁים, “Holy of Holies” (41:3–4).[3] Unlike its counterparts, the temple has no gold, nor cherubim made of gold, nor an Ark of the Covenant, no high priest, and nothing is described in the Holy of Holies.

The sixth century B.C.E. Babylonian milieu, where the Temple Vision was born and where the book’s audience lived, explains why Ezekiel’s visionary temple differs in many ways from the Bible’s descriptions of the Tabernacle and the Temple of Solomon.

The Babylonian Context

Ezekiel would likely have been exposed to Babylonian temple practices during his long sojourn there—from 597 B.C.E., when he was exiled with Jehoiachin and thousands of other captives, until 573 (Ezek 40:1). Indeed, Babylonian temple activities spilled out onto the roads and the city centers, especially during the Babylonian holidays.[4]

Extant ancient descriptions of Babylonian temples provide details about their architectural structure and in several cases even provide their exact dimensions.[5] Ezekiel’s temple has many features in common with the temples described in these texts, including the large wall surrounding the entire consecrated area and the use of gates and passages to restrict access to the temple to authorized temple personnel.[6]

The Ezida Temple

Among the temple plans discovered to date, the one most similar to Ezekiel’s temple is the Ezida temple of Borsippa, the second most important temple in Babylonia between the years 750–484 B.C.E. Built at the end of the second millennium B.C.E. and consecrated to the god Nabû, the servant-chronicler of Marduk, the head of the Babylonian pantheon, the temple was renovated during the time of Nebuchadnezzar II, the king who destroyed the kingdom of Judah.[7]

The ancient texts describing the Borsippa temple have not been fully reconciled with the archeological discoveries from the site.[8] It is possible nevertheless to point to a similarity between the basic plan of Ezekiel’s temple and the Borsippa texts:

Large courts are adjacent to inner and outer rooms. The archeological discoveries at the Borsippa site confirm the large size of the courts.

Outer rooms serve as entrances to the inner room. The location and purpose of the chambers in the courts of the temple of Ezekiel are similar to those of the temple of Ezida.

A terraced entrance leads from a less holy area to the most holy area, which was also the most carefully protected. In Borsippa, priests entered the temple via the main gate into the court, passing through several rooms, through another gate (the gate of Nabû), to the private area of Nabû, and only from there to the innermost, holiest place.

Ezida’s Temple Personnel

The Babylonian texts also describe how various measures were taken at Ezida to ensure that the god’s place in the temple was separate and distinct from the rest of the holy precinct. The priests belonged to families whose priestly ancestry was traced back many generations, and they divided into different ranks, with a priest’s rank determining his degree of access to various parts of the temple complex. Status within the priesthood in general was based not only on family origin, but also on the priest’s role in the temple and his suitability to this role.

The members of the highest echelon held pivotal positions. By virtue of their stature, they were allowed to enter the central area of the temple where they were responsible for the performance of the most central ritual functions. Documents from the sixth century B.C.E. suggest that the priests serving the cult-image would have had to meet the highest standards of lineage.[9] Those of secondary importance were only permitted to enter the court.

These detailed accounts of how priestly families divided their resources over the generations, and the various ritual functions performed in the hundreds of different temple chambers, help bring to life the distinction between the priests and Levites in Ezekiel.

The Zadokite Priests and the Levites

In Ezekiel, the priests of the line of Zadok are highest in rank, and therefore serve closest to YHWH:[10]

יחזקאל מד:טו וְהַכֹּהֲנִים הַלְוִיִּם בְּנֵי צָדוֹק אֲשֶׁר שָׁמְרוּ אֶת מִשְׁמֶרֶת מִקְדָּשִׁי בִּתְעוֹת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל מֵעָלַי הֵמָּה יִקְרְבוּ אֵלַי לְשָׁרְתֵנִי וְעָמְדוּ לְפָנַי לְהַקְרִיב לִי חֵלֶב וָדָם נְאֻם אֲדֹנָי יְ־הוִה. מד:טז הֵמָּה יָבֹאוּ אֶל מִקְדָּשִׁי וְהֵמָּה יִקְרְבוּ אֶל שֻׁלְחָנִי לְשָׁרְתֵנִי וְשָׁמְרוּ אֶת מִשְׁמַרְתִּי.

Ezek 44:15 But the levitical priests descended from Zadok,…they shall approach Me to minister to Me; they shall stand before Me to offer Me fat and blood—declares the Lord YHWH. 44:16 They alone may enter My Sanctuary and they alone shall approach My table to minister to Me; and they shall keep My charge.

The Levites, on the other hand, may serve in the temple complex, as in the past; they will guard the gates and slaughter the burnt and well-being offerings, but they are not permitted to enter the inner sections:

יחזקאל מד:יא וְהָיוּ בְמִקְדָּשִׁי מְשָׁרְתִים פְּקֻדּוֹת אֶל שַׁעֲרֵי הַבַּיִת וּמְשָׁרְתִים אֶת הַבָּיִת הֵמָּה יִשְׁחֲטוּ אֶת הָעֹלָה וְאֶת הַזֶּבַח לָעָם וְהֵמָּה יַעַמְדוּ לִפְנֵיהֶם לְשָׁרְתָם.... מד:יג וְלֹא יִגְּשׁוּ אֵלַי לְכַהֵן לִי וְלָגֶשֶׁת עַל כָּל קָדָשַׁי אֶל קָדְשֵׁי הַקְּדָשִׁים.... מד:יד וְנָתַתִּי אוֹתָם שֹׁמְרֵי מִשְׁמֶרֶת הַבָּיִת לְכֹל עֲבֹדָתוֹ וּלְכֹל אֲשֶׁר יֵעָשֶׂה בּוֹ.

Ezek 44:11 They shall be servitors in My Sanctuary, appointed over the Temple gates, and performing the chores of My Temple; they shall slaughter the burnt offerings and the sacrifices for the people. They shall attend on them and serve them…. 44:13 They shall not approach Me to serve Me as priests, to come near any of My sacred offerings, the most holy things…. 44:14 I will make them watchmen of the Temple, to perform all its chores, everything that needs to be done in it.”

Leviticus vs. Ezekiel

We do not have a detailed account of priestly ritual from the time of the First Temple that might explain some of the differences between Leviticus’s description of sacrifice in the Tabernacle and what we find in Ezekiel’s temple. It is nonetheless clear that a significant change occurs in Ezekiel: all three social classes—priests, Levites, and Israelites—are described as being farther removed from the consecrated areas than they are in the Torah.

Priests – In Leviticus, priests could enter הַקֹּדֶשׁ, “the Sanctuary,” and the High Priest was even commanded to enter the Holy of Holies (Lev 16:2), while in Ezekiel, the priests are not allowed to enter the Holy of Holies and, in some cases, possibly not even allowed to enter the Sanctuary; they perform their tasks primarily in the inner court (44:15–17).

Levites – In Leviticus, the Levites are permitted as far as the court of the Tabernacle (i.e., to the פֶּתַח אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד, “entrance of the Tent of Meeting”). In Ezekiel, the Levites are permitted to be in the inner court, but they cannot approach the altar at its center.[11]

Israelites – In Leviticus, the people (non-priests, non-Israelites) are allowed as far as the court of the Tabernacle. When an offering is sacrificed in the court, the animal is slaughtered by the Israelite bringing the sacrifice (with the exception of the bird offering, where the priest severed the head), while the priests dash the blood on the altar and place the parts of the sacrifice there (Lev 1–3). According to Ezekiel’s vision, when the people come to the temple on festivals, they are forbidden from entering the inner court and can only to stand at the entrance to the outer court (Ezek 44:19). They also do not slaughter their sacrifices themselves; this task is given to the Levites (Ezek 44:11).

Foreigners – An additional group, furthest removed of all, are the foreigners, whose presence defiles the temple (Ezek 7:21–22); they are prohibited from even entering the temple compound (44:6–9).

As a result of these changes, Ezekiel transforms the courts into the center of activity in the temple, with only a few, select priests permitted to enter the consecrated areas, and denies the common people access to the inner areas of the consecrated ground. The goal of these changes is to more scrupulously safeguard the ritual sanctity of the future temple, and thus avoid offending YHWH.

A New Name for Jerusalem

A central theme in the opening chapters of Ezekiel is YHWH’s condemnation of the activities occurring in the First Temple and His departure from Jerusalem (chs. 8–11):

יחזקאל יא:כג וַיַּעַל כְּבוֹד יְ־הוָה מֵעַל תּוֹךְ הָעִיר וַיַּעֲמֹד עַל הָהָר אֲשֶׁר מִקֶּדֶם לָעִיר.

Ezek 11:23 The Presence of YHWH ascended from the midst of the city and stood on the hill east of the city.[12]

Ezekiel refers to this earlier vision in his Temple Vision when he describes YHWH’s return to the city:

יחזקאל מג:ב וְהִנֵּה כְּבוֹד אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל בָּא מִדֶּרֶךְ הַקָּדִים וְקוֹלוֹ כְּקוֹל מַיִם רַבִּים וְהָאָרֶץ הֵאִירָה מִכְּבֹדוֹ. מג:ג וּכְמַרְאֵה הַמַּרְאֶה אֲשֶׁר רָאִיתִי כַּמַּרְאֶה אֲשֶׁר רָאִיתִי בְּבֹאִי לְשַׁחֵת אֶת הָעִיר וּמַרְאוֹת כַּמַּרְאֶה אֲשֶׁר רָאִיתִי אֶל נְהַר כְּבָר וָאֶפֹּל אֶל פָּנָי.

Ezek 43:2 And there, coming from the east with a roar like the roar of mighty waters, was the Presence of the God of Israel, and the earth was lit up by His Presence. 43:3 The vision was like the vision I had seen when I came to destroy the city, the very same vision that I had seen by the Chebar Canal. Forthwith, I fell on my face.

YHWH then fills the new temple:

יחזקאל מג:ד וּכְבוֹד יְ־הוָה בָּא אֶל הַבָּיִת דֶּרֶךְ שַׁעַר אֲשֶׁר פָּנָיו דֶּרֶךְ הַקָּדִים. מג:ה וַתִּשָּׂאֵנִי רוּחַ וַתְּבִיאֵנִי אֶל הֶחָצֵר הַפְּנִימִי וְהִנֵּה מָלֵא כְבוֹד יְ־הוָה הַבָּיִת.

Ezek 43:4 The Presence of YHWH entered the Temple by the gate that faced eastward. 43:5 A spirit carried me into the inner court, and lo, the Presence of YHWH filled the Temple.

In the final verse of the Temple Vision, the city is given a new name:

יחזקאל מח:לה ...וְשֵׁם הָעִיר מִיּוֹם יְ־הוָה שָׁמָּה.

Ezek 48:35 …And the name of the city from that day on shall be “YHWH Is There.”

While the name reflects the theme of YHWH’s departure and return, it may also have been influenced by the Babylonian practice of including the god’s name in the name of the city. For example, the name of the city of Nippur is written EN.LÍLki , “(the place) [of the god] Enlil,” but is pronounced as Nippur.

Ezekiel’s Temple in Context

The increase in knowledge of the structure and functioning of Babylonian temples suggests that Ezekiel the exiled priest-prophet interacted within his Babylonian context in his prophetic vision of the future temple, which is rooted in the conceptual world of the Neo-Babylonian period.[13] The comparison of the biblical text with textual information about local temples in this period sharpens, highlights, and explains several unique characteristics of Ezekiel’s visionary temple, as distinct from the Tabernacle and the Temple of Solomon, and clarifies how Ezekiel’s prophecy was received by his local contemporaries, who were living in a Babylonian context and surrounded by Babylonian temples.

Ezekiel does not simply rebuild Solomon’s Temple or copy Babylonian practices but creates a new visionary temple cult committed to YHWH as the one true God. By focusing on structural and ritual features that would safeguard the sanctity of the temple compound, Ezekiel works to ensure that the Divine Presence will remain there for eternity—a clear response to the Babylonian destruction of the First Temple in 586 B.C.E.[14]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 2, 2023

|

Last Updated

February 7, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Tova Ganzel is an Associate Professor in the Multidisciplinary Department of Jewish Studies and serves as the head of Olamot, the School of Jewish and Israeli Culture, at Bar-Ilan University. Within the Multidisciplinary Department, she founded the Cramim Honors Program in Jewish Studies. Her research focuses on the Hebrew Bible within the broader context of the ancient Near Eastern world, with special emphasis on prophetic literature and temple-centered communities, and also explores the Book of Ezekiel in light of Neo-Babylonian culture, and the temple and its community during the Persian period, especially in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Her work also examines the development of biblical criticism in Jewish thought from the eighteenth century onward, and the role of women as Halakhic professionals.

Essays on Related Topics: