Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Laughter! Between Isaac and Aqhat’s Birth Pronouncements

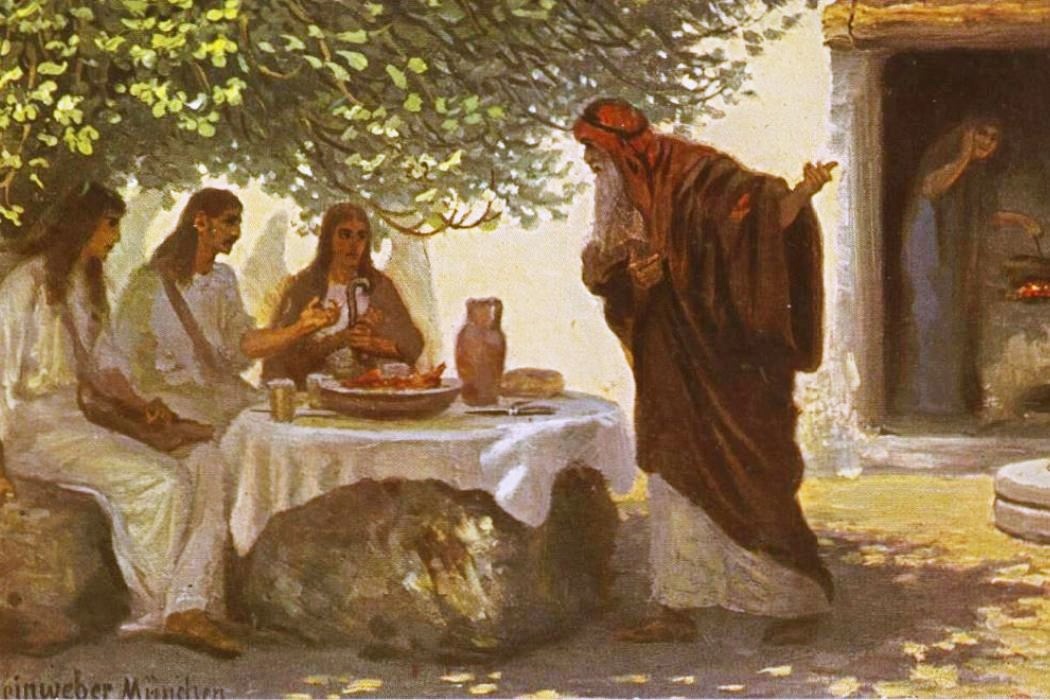

Abraham and the three angels, Robert Leinweber(1845- 1921). Lowcountry Digital Library

The name Yitzhak (=Isaac) means “he laughs,” and indeed, the three separate references to his birth are accompanied by different people laughing.

Sarah predicts that people will laugh when they hear of the birth of Isaac because, as she notes, Abraham was so old:

בראשית כא:ה וְאַבְרָהָם בֶּן מְאַת שָׁנָה בְּהִוָּלֶד לוֹ אֵת יִצְחָק בְּנוֹ. כא:ו וַתֹּאמֶר שָׂרָה צְחֹק עָשָׂה לִי אֱלֹהִים כָּל הַשֹּׁמֵעַ יִצְחַק לִי. כא:ז וַתֹּאמֶר מִי מִלֵּל לְאַבְרָהָם הֵינִיקָה בָנִים שָׂרָה כִּי יָלַדְתִּי בֵן לִזְקֻנָיו.

Gen 21:5 Now Abraham was a hundred years old when his son Isaac was born to him. 21:6 Sarah said, “God has brought me laughter;[1] everyone who hears will laugh for me.” 21:7 And she added, “Who would have said to Abraham that Sarah would suckle children! Yet I have borne a son in his old age.”[2]

Indeed, this is how Sarah herself reacts earlier when the divine messengers announce the impending pregnancy and birth to Abraham, and the text explains why:

בראשית יח:יא וְאַבְרָהָם וְשָׂרָה זְקֵנִים בָּאִים בַּיָּמִים חָדַל לִהְיוֹת לְשָׂרָה אֹרַח כַּנָּשִׁים. יח:יב וַתִּצְחַק שָׂרָה בְּקִרְבָּהּ לֵאמֹר אַחֲרֵי בְלֹתִי הָיְתָה לִּי עֶדְנָה וַאדֹנִי זָקֵן.

Gen 18:11 Now Abraham and Sarah were old, advanced in years; Sarah had stopped having the periods of women. 18:12 And Sarah laughed in her head, saying: “Now that I am worn out, could I experience pleasure?! And my master is old!”

Here Sarah expresses the absurdity of their having a child in terms of both of their advanced ages. Abraham reacts the same way when God first tells him that in the previous chapter that Sarah will birth a son:

בראשית יז:יז וַיִּפֹּל אַבְרָהָם עַל פָּנָיו וַיִּצְחָק וַיֹּאמֶר בְּלִבּוֹ הַלְּבֶן מֵאָה שָׁנָה יִוָּלֵד וְאִם שָׂרָה הֲבַת תִּשְׁעִים שָׁנָה תֵּלֵד.

Gen 17:17 Abraham fell on his face, laughed (ויצחק), and said to himself: “Could a child be born to a 100-year-old man?! And could 90-year-old Sarah birth a child?!”[3]

Laughter at the wondrous birth of unexpected child also appears in a parallel story from the Ugaritic Aqhat Epic (ca.14th cent. B.C.E., Syria).

The Aqhat Epic

The Aqhat Epic opens with the plight of a legendary man name Danel,[4] likely attested to in Ezekiel 14:14, where he is included in a list of legendary pious characters alongside Noah and Job, and in Ezekiel 28:3, where Danel is implied to be the wisest person to have ever lived. In the Aqhat Epic, Danel is desperate for a male heir and tries to convince the gods to grant him one. For seven days he “gives food to the gods, drinks to the deities,” until finally, on the seventh day, he catches the attention of Baʿal:

Then on the seventh day, Baʿal draws near in compassion: “The longing of Danel, man of Rapiu![5] The moan of the hero, man of the Harnemite![6] Who has no son like his siblings, no offspring like that of his fellows. Will he have no son like his siblings, no offspring like that of his fellows? Who, girded, gives food to the gods, girded, gives drink to the deities?[7]

Baʿal intervenes by turning to his father, El, the chief of the gods:

Bless him, Bull El,[8] my father, prosper him, Creator of Creatures. Let him have a son in his house, offspring within his palace.

El agrees to bless Danel, and proclaims that he shall have a son, listing the duties of a son that Danel had previously opined for. Notably, El raises a cup while offering his blessing, much in the way that wine is used in later Jewish kiddush ritual:

El takes [a cup] in his hand. He blesses [Dan]el, man of Rapiu, prospers the hero, [man of the] Harnemite: “By my life,[9] let Danel, [man of] Rapiu thrive, by my soul, the hero, man of Harnemite… flourish! Let him mount his couch… in kissing his wife, [conception], in embracing her, pregnancy! … And a son he will have [in his house, offspring] within his palace.

The tablet is broken shortly thereafter, but resumes with Danel himself being informed of the good news:

Danel’s face beams, his brow above lights up. He laughs (wyṣḥq), sets his foot on the footstool, raises his voice and cries:[10] “Now I’ll sit down and rest, in my breast my heart will rest. Like my siblings, a son’s to be born to me, an offspring like that of my fellows….”

He then enters his home with the Katharat, a unit of seven deities associated with pregnancy and childbirth, and likely the ones who informed Danel of his good luck. Danel slaughters an ox for them, and gives them the meat along with wine:

Danel comes to his house; Danel arrives at his palace. The Katharat enter his house, the moon’s radiant daughters. Now Danel, man of Rapiu, the hero, man of the Harnemite, slaughters an ox for the Katharat, dines the Katharat, and wines the moon’s radiant daughter.

Danel does this for six consecutive days, and on the seventh day, the Katharat leave, and then Danel and his wife experience “the joys of bed…. the delights of the bed of childbirth.” Not long after, Aqhat is born.

Narrative Similarities

The Aqhat Epic shares several commonalities with the Isaac’s-birth narratives:[11]

Divine intervention—In both narratives, the deity announces the birth of the unexpected baby. In Aqhat, the baby is prayed for, but in Genesis, it is announced without having been requested.

Divinity combo—Both Abraham and Danel are approached by deities that blur the boundary between singular and plural entities. Abraham is approached by YHWH (Gen 18:1, 10–14) in the form of three men (Gen 18:2–9),[12] while Danel is approached by Kotharat, a divine combo that is at the same time a divine singular.[13]

Hosting—Abraham (Gen 18:1–8) and Danel both offer their divine guests food and drink.[14]

Sexual pleasure—Danel and his wife are said to experience the pleasures of the bed, and Sarah, stunned to learn that she will get pregnant and have a son, says she can’t believe that at her age, and with her old husband, she’ll have sexual pleasure. This emphasis may reflect a belief that female orgasm was required for successful conception of offspring.[15]

Laughter—Perhaps most striking is what I noted above, that like Abraham and Sarah, Danel laughs when he hears the news.

Danel’s laughter is described using the same verb (צחק/ṣḥq) as Abraham and Sarah, and in the exact same form as Abraham in Genesis 17:17 (ויצחק = wyṣḥq). But while the terminology is identical, the quality of the laughter is quite different.[16]

Birth Pronouncement Laughter: Between Genesis and Aqhat

In Aqhat, when Danel is informed that he will soon father a son, he is unambiguously joyful. The narrator communicates this joy in multiple ways – Danel’s face transitions into a relaxed and joyful pose, he rests his feet, he laughs, and he excitedly exclaims what his son will do for him. Here, laughter is one of many signs of joy and firm belief in the veracity of the divine proclamation. This type of laughter - joyful laughter that occurs without thought, in response to a stimulus - is referred to in scientific literature as Duchenne laughter.[17] Non-Duchenne laughter, in contrast, is less of an immediate response to stimulus, and rather more cerebral and calculated, often reflecting irony, discomfort or displeasure.[18]

Instead of reacting like Danel with pure joy, which would indicate complete belief in the word of God, both Abraham and Sarah express skepticism in response to God’s promise that they will bear a son together. The matter is too improbable, the couple simply too old.[19]

Abraham and Sarah’s laughter appears to be nervous or derisive laughter, non-Duchenne laughter. They are not unambiguously joyful. Their laughter is perhaps best interpreted as nervous laughter, since they both do not entirely believe the divine pronouncement and admit as such. As they do not entirely reject it either, they are faced with this uncomfortable situation of an unbelievable divine revelation, and they laugh.[20]

This type of nervous or uneasy laughter may also be part of what Sarah alludes to when she names Isaac: “God has made me a laughing matter – everyone who hears will laugh for me!” (Gen 21:6). Sarah may be predicting that people will laugh for her or at her (יצחק־לי) when they hear the news – this laughter may be joyous, but also skeptical. How could Sarah actually conceive a child at such an advanced age?[21] The focus on age in Genesis may reflect the unique storyline of the birth-of-Isaac narrative in contrast to other birth stories in the Bible and in Aqhat.

A Miracle Story

In the Aqhat Epic, Danel and his wife Danataya must be aging, but apparently can still expect to have a child. This is the same for the biblical stories of Isaac and Rebecca (Gen 25:20), Jacob and Rachel (Gen 29:29, 30:22), or Elkanah and Channah (1 Sam 1–2). The women are getting older, but they are all apparently of childbearing age.[22]

In contrast, central to the Abraham and Sarah cycle is that they have aged out of childbearing years, and God’s promise of an heir has still not materialized (Gen 15:1–6). Indeed, we are told that Sarah is no longer menstruating, and Sarah’s comment (18:12) implies that the couple is no longer sexually active; neither of their bodies function sexually anymore. Physically, they simply can’t have a child—it’s impossible.[23] This has the effect of making Isaac’s birth not just an act of divine intervention but rather a miracle.

The birth is so miraculous that Abraham and Sarah simply cannot believe it. Their laughter may then reflect the pain and skepticism of a couple who have long tried for children, hopeful yet skeptical, perhaps joyful yet self-effacing. Considering the references to Danel in Ezekiel, and multiple connections between the Aqhat Epic and Genesis ancestor stories, it is possible that a version of the story or a similar one was circulating in ancient Israel.

If audiences were familiar with the Aqhat story, the differences in the birth narratives would have at least two major effects: making the birth more miraculous, and also, ascribing more complex emotional laughter to the heroic couple.[24]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

November 4, 2025

|

Last Updated

December 27, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Noam Cohen is Visiting Assistant Professor of Hebrew and Jewish Studies at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, PA. He received his PhD from NYU, with a dissertation examining portrayals of spousal violence in the Hebrew Bible and other ancient West Asian texts.

Essays on Related Topics: