Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Menorah, Its “Branches” and Their Cosmic Significance

Fig. 1. Menorah depicted in Mosaic Pavement, Samaritan Synagogue of el-Hirbe, 5th c. C.E. Photograph by Steven Fine

Attempting to Picture the Menorah

Exodus 25:31–40 describes God’s command to Moses to construct the golden lampstand (menorah) of the Tabernacle.[1]

שמות כה:לא וְעָשִׂיתָ מְנֹרַת זָהָב טָהוֹר מִקְשָׁה תֵּעָשֶׂה הַמְּנוֹרָה יְרֵכָהּ וְקָנָהּ גְּבִיעֶיהָ כַּפְתֹּרֶיהָ וּפְרָחֶיהָ מִמֶּנָּה יִהְיוּ.

Exod 25:31 And you shall make a lampstand of pure gold. The base and the shaft of the lampstand shall be made of hammered work; its cups, its bulbs, and its flowers shall be of one piece with it.

The menorah is described in great and even confusing detail two times in the Torah.[2] This is an almost compulsive word picture, whether in translation or in the original Hebrew. The constant repetition of the need to have almond-shaped cups, bulbs, and flowers is especially opaque:

כה:לג שְׁלֹשָׁה גְבִעִים מְשֻׁקָּדִים בַּקָּנֶה הָאֶחָד כַּפְתֹּר וָפֶרַח וּשְׁלֹשָׁה גְבִעִים מְשֻׁקָּדִים בַּקָּנֶה הָאֶחָד כַּפְתֹּר וָפָרַח כֵּן לְשֵׁשֶׁת הַקָּנִים הַיֹּצְאִים מִן הַמְּנֹרָה.

25:33 three cups made like almonds, each with bulb and flower, on one stalk, and three cups made like almonds, each with bulb and flower, on the other stalk—so for the six branches going out of the lampstand;

כה:לד וּבַמְּנֹרָה אַרְבָּעָה גְבִעִים מְשֻׁקָּדִים כַּפְתֹּרֶיהָ וּפְרָחֶיהָ. כה:לה וְכַפְתֹּר תַּחַת שְׁנֵי הַקָּנִים מִמֶּנָּה וְכַפְתֹּר תַּחַת שְׁנֵי הַקָּנִים מִמֶּנָּה וְכַפְתֹּר תַּחַת שְׁנֵי הַקָּנִים מִמֶּנָּה לְשֵׁשֶׁת הַקָּנִים הַיֹּצְאִים מִן הַמְּנֹרָה. כה:לו כַּפְתֹּרֵיהֶם וּקְנֹתָם מִמֶּנָּה יִהְיוּ כֻּלָּהּ מִקְשָׁה אַחַת זָהָב טָהוֹר.

25:34 and on the lampstand itself four cups made like almonds, with their bulbs and flowers, and a bulb of one piece with it under each pair of the six branches going out from the lampstand. 25:36 Their bulbs and their branches shall be of one piece with it, the whole of it one piece of hammered work of pure gold.

Many times I have asked students to leave their preconceptions behind and to draw what they read based on the text alone, or to listen carefully when it is read aloud and imagine its form; they find it virtually impossible to imagine what is being described. Most students agree that the menorah is a kind of overgrown plant, complete with branches, bulbs and flowers. Beyond that there is little consensus, prompting great discussions.

Envisioning the real menorah behind the biblical text is no easy task. We do not live within the same visual culture that biblical Israel did. It is like asking a contemporary teen to imagine a samovar in a Shalom Aleichem story, without ever having seen one or having been served tea from one.

Commentators from antiquity to the present tend to focus on the detailed philological study of the menorah, word by word. My sense, though, is that the tabernacle texts are far more poignant when read out loud in a public performance, as they are in the synagogue. The voice of the reader fills spaces between the words, and drives our experience forward from object to object. There is no time to linger. This creates a kind of impressionistic listening, with each detail of the biblical description melting into the whole.

Art provides a visual example to explain my point. When you look at a painting by the impressionist Claude Monet up close, all you can see are brush strokes, colors and shapes. Only at a distance does the Monet painting come into focus and present a coherent whole—an “impression” (Figs. 2-3). So too the Tabernacle vessels.

|

|

|

Moses Doesn’t Understand What to Do (Midrash Tanḥuma)

Ancient rabbis were aware that something is missing in the text of the Torah that hampers our understanding of it. A story preserved in Midrash Tanḥuma (ca. 8th century), for example, imagines that Moses was unable to visualize the object described to him by God. This midrash plays off the final verse in the menorah passage (Beha’alotecha 11, Buber ed.):

שמות כה:מ וּרְאֵה וַעֲשֵׂה בְּתַבְנִיתָם אֲשֶׁר אַתָּה מָרְאֶה בָּהָר.

Exod 25:40 And see that you make them after the pattern for them, which is being shown you on the mountain.

Noting that Moses had to be shown an image and that Bezalel is the one to build it, this midrash reports:

ר' לוי אמר מנורה טהורה ירדה מן השמים,

R. Levi says: “A pure menorah came down from heaven.”

למה? שאמר לו הקדוש ברוך הוא למשה ועשית מנורת זהב טהור,

How is this? For the Holy One, blessed be He, said to Moses, “And you will make a menorah of pure gold” (Exodus 25:31).

א"ל כיצד נעשה,

[Moses] said to Him: ‘How shall we make it?’

א"ל מקשה תעשה המנורה,

[God] said to him: “Of beaten work shall the menorah be made” (ibid.)

אעפ"כ נתקשה משה, וירד ושכח מעשיה,

Nevertheless, Moses still found difficulty with it, and when he came down, he forgot its construction.

עלה ואמר רבש"ע שכחתי,

He went up and said: “Master of the Universe, I have forgotten [how to make it]!”

א"ל ראה ועשה, שנטל מטבע של אש, והראה לו עשייתה, ועוד נתקשה על משה,

He [God] said to him: “Look and make (it),” He made its form out of fire and showed him its construction. Still, he [Moses] found its construction difficult.

א"ל הקדוש ברוך הוא לך אצל בצלאל והוא יעשה אותה,

So the Holy One, blessed be He said to him: “Go to Bezalel and he will make it.”

ירד משה ואמר לבצלאל, מיד עשאה,

He went down and told Bezalel, who immediately did it.

התחיל משה תמיה, ואמר אני כמה פעמים הראה לי הקדוש ברוך הוא ונתקשיתי לעשותה, ואתה שלא ראית עשית מדעתך, בצלאל שמא בצל אל היית עומד כשהראה לי הקדוש ברוך הוא,

Moses began to wonder, saying: “To me it was shown many times by the Holy One, blessed be He, yet I found it hard to make, and you who did not see it constructed it with your own intelligence! Bezalel, perhaps you were standing in the shadow of God (be-tzel El) when the Holy One, blessed be He, showed me its construction?!”[3]

In seeming frustration, the Divine was forced to show Moses a fiery prototype of the lampstand. Even that was too difficult for him. Embarrassingly for Moses, Bezalel ben Uri—literally translated as “in the shadow of God, son of light,” a most auspicious name— proved up to the task.[4] Here, Moses the auditory learner is no match for the tactile Bezalel!

The Cups, Buds, and Flowers Are a Hidden Mystery (Nahmanides)

Moses Nahmanides (Ramban, d. 1270), commenting on Exodus 25:30–31, writes that “cups, bulbs and flowers” of the menorah are something of a mystery, referencing our Tanhuma midrash:

חכמת המנורה בגביעיה וכפתוריה ופרחיה מאין תמצא, ונעלמה מאד—אבל היותה מקשה בששה קנים יוצאין מן השביעי ועליהם נר אלהים, ומאירים כלם אל עבר פניה, כל זה תוכל להבין מדברינו שכתבנו במקום אחר—וזה מאמרם: שנתקשה משה במנורה.

The wisdom of the menorah, of its cups, bulbs, and flowers, from whence will you find it, as it is well hidden—Nevertheless, its construction from one block of gold, with six branches extending out from the seventh, and upon them divine lamps which all light up the space in front of it,[5] all this can be understood from what we have written in explanation elsewhere—This is the meaning of [the Rabbis’] claim that Moses had difficulty with the lampstand.

Nahmanides here is playing off a passage in Job:

איוב כח:כ וְהַחָכְמָה מֵאַיִן תָּבוֹא וְאֵי זֶה מְקוֹם בִּינָה. כח:כא וְנֶעֶלְמָה מֵעֵינֵי כָל חָי וּמֵעוֹף הַשָּׁמַיִם נִסְתָּרָה.

Job 28:20 Whence then comes wisdom? And where is the place of understanding? 28:21 It is hidden from the eyes of all living, and concealed from the birds of the air.

Indeed, figuring out where to place the cups, bulbs and flowers, is no easy matter. Even the details of the “branches” and how they extend out of the base, which Nahmanides describes as understandable, have been a subject of dispute.

What Are the Menorah’s Qanim?

The Torah text explains that the menorah is to have six qanim coming out of the central shaft:

שמות כה:לב וְשִׁשָּׁה קָנִים יֹצְאִים מִצִּדֶּיהָ שְׁלֹשָׁה קְנֵי מְנֹרָה מִצִּדָּהּ הָאֶחָד וּשְׁלֹשָׁה קְנֵי מְנֹרָה מִצִּדָּהּ הַשֵּׁנִי.

Exod 25:32 and there shall be six branches (or, “stalks,”) going out of its sides, three branches of the lampstand out of one side of it and three branches of the lampstand out of the other side of it;

The standard translation of qanim is “branches,” based on the image of menorah as having looked like a plant, a kind of near-eastern “tree of life.” Some have even associated it with a specific plant, namely “reeds,” hollow tube-like plants that grow near bodies of water. For this reason, the Septuagint rendered qanim as kalamiskos (καλαμίσκος), “tubes,” imagining, as we will see, something like reeds.

There are no biblical or rabbinic instructions on how to fashion the qanim. The ancient rabbis as well as most other interpreters are silent on whether the branches were straight or rounded. The vast majority of visual and textual interpreters have assumed rounded branches, a tradition so firm that it did not require discussion.

Straight Branches: from Maimonides to Menachem Mendel Schneerson

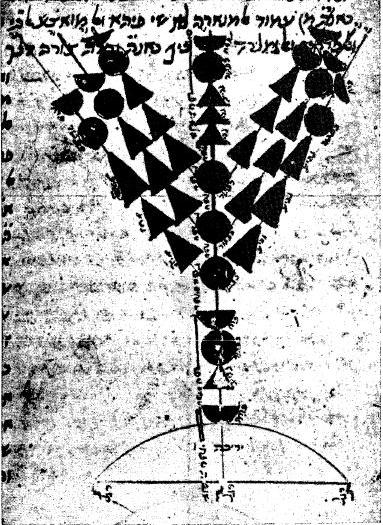

A notable exception to this interpretive tradition may have been the twelfth century scholar Moses Maimonides (Rambam, d. 1204), In his handwritten manuscript of his Mishnah commentary (now at Oxford University), the Rambam drew a schematic menorah with straight branches (fig. 4).[6]

It is a very poorly crafted image, covering in places the text of the Commentary itself. Maimonides admits in his commentary that his drafting skills are not well developed. His drawing is meant as a visual aid for his larger discussion of the locations of the menorah’s bulbs and flowers. The menorah itself is schematic, a place to hang his discussion of bulbs and flowers. His son Abraham, an important scholar in his own right, wrote in his commentary on Exodus (ad loc.) that his father intended straight branches:

וששה קנים—הקנים (כמו) ענפים נמשכים מגופה של מנורה לצד ראשה ביושר, כמו שצייר אותה אבא מרי ז"ל, ולא בעיגול כמו שצייר אותה זולתו.[7]

“Six qanim”—the qanim (are like) branches that extend from the base of the lampstand towards its head in a straight line, just as my father of blessed memory drew it, and not in an arc, like others have drawn it.

Rambam’s image was copied diligently in later generations. Manuscripts are preserved from medieval Spain and from Yemen. These scribes copied the menorah as Maimonides drew it, with straight branches. This visual tradition was unnoticed until it was brought to public attention by Yemenite-Israeli Rabbi Yosef Qafih in his edition of Maimonides’s Mishnah commentary (Jerusalem, 1964), and popularized by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, during the 1990’s.

Arched Branches: The Standard Interpretation

A straight-branched menorah, however, was never widely accepted. In fact, while the Torah is admittedly unclear on how the branches were shaped, the actual depiction of the menorah has been quite stable. The earliest image appears on a coin of the Hasmonean Mattathias Antigonus (39 B.C.E.), who minted a small bronze coin (a perutah in Hebrew, lepton in Greek) with the image of a seven-branched menorah, its parallel branches arching up from the sides of the central stalk, and culminating at the same line at the height of the central lamp (fig. 5).

Thousands of examples of menorahs of similar shape are known, including one on the recently discovered ashlar from the Migdal synagogue (1st. century CE, fig. 6) and of course, the Arch of Titus menorah, (fig. 7).[8] This shape was also used by Samaritans (fig. 1, above) in antiquity and by Christians in medieval Europe.

|

|

|

It is hard to find a Jewish menorah that does not fit this model—and historically, those that don’t were often created by inferior craftsmen; drawing a menorah with parallel rounded branches is actually pretty difficult!

Cosmic Interpretation in the Second Temple Period

Second Temple period interpreters, writing in Greek, explained the menorah, its seven lights and the rounded branches, in astronomical terms. Each parallel branch represents the heavenly course of the “planet” that sits atop it. Together, they represent the cosmos.

Philo of Alexandria

Philo of Alexandria, writing during the first third of the first century C.E., directly relates the shape of the menorah’s rounded branches to the trajectory of the planets around the sun:

He says that the approach to them is from the side (and) the middle place is that of the sun. But to the other [“planets”] He distributed three positions on the two sides [of the lampstand]; in the superior [group] are Saturn, Jupiter and Mars, while in the inner [group] are Mercury, Venus and the moon.[9]

Philo is the first author to provide context for the rounded branches, associating them with his larger astral concerns. This approach hearkens back to an association of the lamps of the lampstand with the planets that first appears in the prophet Zechariah already during the sixth century B.C.E., who described the five visible planets, plus the sun and the moon, as the “eyes of YHWH:”

זכריה ד:י שִׁבְעָה אֵלֶּה עֵינֵי יְ־הוָה הֵמָּה מְשׁוֹטְטִים בְּכָל הָאָרֶץ.

Zech 4:10 …These seven are the eyes of YHWH, which range through the whole earth.

In The Life of Moses, Philo goes further in associating the menorah with the cosmos:

The candlestick he [Moses] placed at the south [of the Tabernacle] figuring thereby the movements of the luminaries above; for the sun and the moon and the others run their courses in the south far away from the north. And therefore six branches, three on each side, issue from the central candlestick, bringing up the number to seven, and on all these are set seven lamps and candle bearers, symbols of what the men of science call planets. For the sun, like the candlestick, has the fourth place in the middle of the six and gives light to the three above and the three below it, so tuning to harmony an instrument of music truly divine.[10]

The rounded branches thus give expression to this “music truly divine,” supporting the planets in their paths, even as they support the lights of this rather lanky artifact.

Josephus

A generation later, Josephus explains the branches in a similar manner. In Jewish War 5.216-17 he describes “the seven lamps (such being the number of lamps from the lampstand) represent the planets.”[11] He returned to this theme around 90 C.E. in his magnum, Antiquities of the Jews, where Josephus ostensibly describes the menorah of the Tabernacle:

Facing the table, near the south wall, stood a candelabrum of cast gold, hollow, and of the weight of a hundred minae; this (weight) the Hebrews call kinchares, a word which, translated into Greek, denotes a talent. It was made up of globules and lilies, along with pomegranates, and little bowls, numbering seventy in all; of these it was composed from a single base right up to the top, having been made to consist of as many portions as assigned to the planets with the sun. It terminated in seven kefalas (κεφαλὰς) “branches” [literally “head”] regularly disposed in a row. Each branch [head] bore one lamp, recalling the number of planets; the seven lamps faced southwest, and the candelabrum being placed crosswise.[12]

Philo and Josephus thus explain the menorah as a representation of the cosmic order. This interpretation might have seemed quite reasonable to a Roman audience. I am reminded, for example, of a silver statuette of the goddess Tutela, the heads of seven planetary deities set on an arc above her in the heavens (fig. 8).[13] Roman readers and viewers may have made this connection as well. Similarly, each of the branches of the menorah supports one of the heavenly luminaries—Zechariah’s “eyes of YHWH.”

Yannai the Poet

While this interpretation is not common among the early rabbis, it does appear in somewhat later sources. For example, the sixth century synagogue poet Yannai puts it this way:

מְנוֹרַת שִׁבְעָה נֵירוֹת מָטָּה,

נִדְמוּ לְשִׁבְעַת מַזְּלוֹת מָעְלָה.

The seven lamps of the menorah below

Are like the seven constellations [planets] above.[14]

Making Meaning out of a Confusing Text

The biblical description of the Tabernacle menorah is indeed difficult to conceptualize. Each element of this complex artifact is open to interpretation, and attempts to visualize the original artifact can be perplexing. Philo, Josephus, and then Yannai opted for an astrological interpretation. Ancients had a profound awareness that “God is watching us from a distance.” The menorah represented this connection.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 25, 2020

|

Last Updated

February 7, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Steven Fine is a Distinguished Professor at Yeshiva University (New York, NY) and holds the Churgin Chair of Jewish History. He is founding director of the YU Center for Israel Studies. Fine’s numerous books include Sacred Realm: The Emergence of the Synagogue in the Ancient World (1997), Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman World: Toward a New Jewish Archaeology (2005) and The Menorah: From the Bible to Modern Israel (2016). Fine recently announced the multi-year YU Archaeology and the Talmud Project.

Essays on Related Topics: