Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Moses’ Shining or Horned Face?

Fig. 1. Statue of Moses by Michelangelo Buonarroti, ca. 1513-1515. Wikimedia

After receiving a second set of stone tablets containing YHWH’s commandments, Moses comes down Mount Sinai with a face that has changed:

שמות לד:כט ...וּמֹשֶׁה לֹא יָדַע כִּי קָרַן עוֹר פָּנָיו בְּדַבְּרוֹ אִתּוֹ. לד:ל וַיַּרְא אַהֲרֹן וְכָל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶת מֹשֶׁה וְהִנֵּה קָרַן עוֹר פָּנָיו וַיִּירְאוּ מִגֶּשֶׁת אֵלָיו.

Exod 34:29 …Moses did not know that the skin of his face was qāran-ed because he had been talking with him (=YHWH). 34:30 When Aaron and all the Israelites saw Moses, the skin of his face was qāran-ed, and they were afraid to come near him.[1]

Moses’ Face in the Ancient Versions

Modern translations consistently render the word qāran (ק.ר.נ) as “shone” (NRSV) or “was radiant” (NJPS). This translation stands in a long and venerable line of tradition, which renders the Hebrew קָרַן עוֹר פָּנָיו “the skin of his face qāran-ed” as:

- LXX (Greek Septuagint)—“the appearance of the skin of his face was charged with glory”;[2]

- Syriac Peshitta—אזדהי משׁכא דאפוהי “the skin of his face shone”;[3]

The Aramaic Targum translations take a similar approach, but they also avoid the word skin:

- Targum Onqelos—סְגִי זִיו יְקָרָא דְּאַפּוֹהִי “the radiance of the glory of his face increased”;[4]

- Targum Pseudo-Jonathan—אשׁתבהר זיו איקונין דאנפוי “the splendor of the features of his face shone”;[5]

- Fragmentary Targum—שׁבחו זיווהון דאפיה “the splendor of [his] face became greater.”[6]

- Targum Neofiti—נהר זיו איקרהון דאפוי “the splendor of the glory of Moses’ face shone”;[7]

- Samaritan Targum—יקר זיב אפיו “the radiance of his face became greater.”[8]

These targums appear to translate the word “skin” (עור) as if it were the word “light” (אור).[9] They may have misheard or misread the term—whether intentionally or otherwise—since the two are quite similar both graphically and phonologically.[10]

That Moses’ face was glowing or shining is also the standard understanding of the text in most medieval Jewish commentaries. While this seems, at first glance, like a sensible translation, it seems to ignore the meaning of the verb קָרַן/qāran.

Moses Grew Horns

קָרַן/qāran is apparently a denominative verb derived from the noun קֶרֶן/qeren, “horn.” The verb occurs only four times in the Bible,[11] but the noun is used dozens of times in the biblical text. If the verb does come from the noun, then qāran suggests that Moses’ face was “horned” in some fashion. In fact, the only other time that this verb occurs in the Hebrew Bible, it means to actually have horns:

תהלים סט:לא אֲהַלְלָה שֵׁם אֱלֹהִים בְּשִׁיר וַאֲגַדְּלֶנּוּ בְתוֹדָה. סט:לב וְתִיטַב לַי־הוָה מִשּׁוֹר פָּר מַקְרִן מַפְרִיס.

Ps 69:31 I will praise the name of God with a song; I will magnify him with thanksgiving. 69:32 This will please YHWH more than an ox or a bull with horns and hoofs.

Thus, Aquila—a second century C.E. Jewish Greek translation of the Bible—rendered the phrase “his face skin became horned.”[12] Similarly, Jerome’s fourth century C.E. Latin Vulgate translation renders it as cornuta esset facies sua, “his face was horned.” Jerome is famous for his interest in “Hebrew Truth” (Hebraica Veritas)—returning to the Hebrew original and hewing as close to it as possible, which may explain his more wooden rendering here.[13]

Under the influence of the Vulgate’s translation, the image of the horned Moses became quite common in medieval art (fig. 2). According to Ruth Mellinkoff, such depictions of Moses are first attested in eleventh-century England,[14] but the image is most familiar from Michelangelo’s famous sixteenth-century sculpture of Moses in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome, which places small horns atop Moses’ head (fig. 1, main image).

The above suggests that understanding qāran as “to shine” may be, at best, a paraphrase, and at worst, an obfuscation. Rather than “to shine,” “to be horned” or “to have horns” seems a reasonable and justifiable translation for qāran.

Polemical Response

Not all would agree. Rabbi Samuel ben Meir (Rashbam ca. 1085–1158), responds polemically to the Vulgate translation of Exod 34:29, which dominated medieval Christianity:

לשון הוד, וכמוהו: קרנים מידו לו. והמדמהו לקרני ראם קרניו אינו אלא שוטה, כי שתי מחלקות הם ברוב תיבות שבתורה.

[The word קרן is] related to the idea of הוד – grandeur. It is like the word קרנים in the phrase (Hab 3:4), “which gives off rays (קרנים) on every side.” Anyone who connects קרן, in this verse, to the meaning of “horn,” as in the phrase (Deut 33:17), “He has horns like the horns of the wild ox (קרני ראם קרניו),” is a fool. For many words in the Torah have [at least] two [separate, distinct] categories [of meaning].[15]

Rashbam supports the traditional (Jewish) reading with a verse from Habakkuk, based on the parallelism in the verse between brightness/daylight and “horns”:

חבקוק ג:ד וְנֹגַהּ כָּאוֹר תִּהְיֶה קַרְנַיִם מִיָּדוֹ לוֹ...

Hab 3:4 The brightness was like daylight; rays came forth from his hand…[16]

We seem caught between two very different understandings: Was Moses’ face shining or was it sprouting horns? Non-textual evidence from ancient Near Eastern iconography may cast light on this question.

Moses’ Face and Ancient Near Eastern Iconography

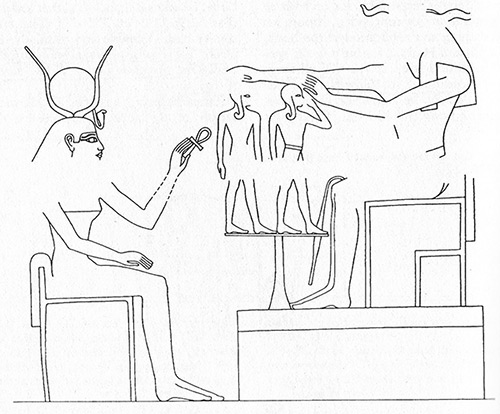

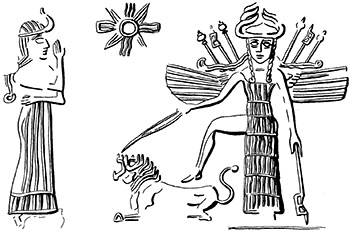

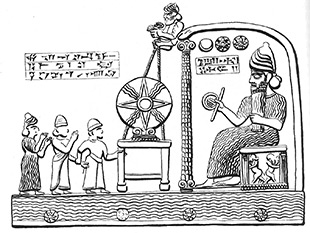

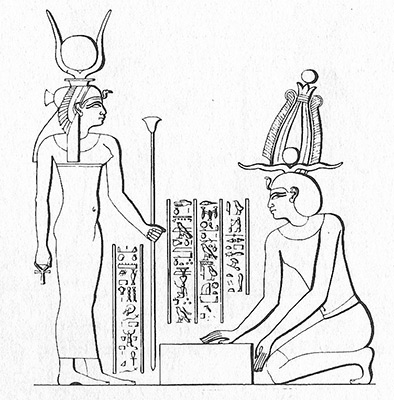

Ancient Near Eastern divinities were often portrayed with horns.[17] Sometimes the horns were part of the deities’ bodies (fig. 3); at other times they appear as stacks of horns worn as or on a headdress (figs. 4-5). In some cases, various anthropomorphic figures are identifiable as gods in ancient art only by means of the presence of horns. Without horns was artistic “code” signifying that the figure was (likely merely) human; with horns meant the figure was divine.[18] A further calculus is often present: the more horns, the higher the god’s status in the pantheon.

|

|

Naram-Sin: A Horned Human

Horns on human individuals are quite rare, but, when present, are significant. An example from Mesopotamia is the victory stele of Naram-Sin (fig. 6). In this image, which dates to ca. 2250 B.C.E., the great king of Agade is portrayed with horns, not unlike the gods.

In Naram-Sin’s case, his horns are connected to his conical helmet. Naram-Sin himself is thus not a god—not yet at least[19]—since at least one god (if not two) is represented at the very top of the stele by means of astronomical symbols.[20] Even so, Naram-Sin is at the very least god-like, a point signaled not only by his horned helmet, but through his large stature and obvious military prowess.

Egyptian Rulers with Horns

In Egypt, other god-like rulers also occasionally portrayed themselves with horns. The atef (fig. 7) and hmhm (“The Roaring One”) crowns had horns as part of the headdress; the latter, notably, may have served to identify the king with the solar deity at sunrise.[21]

Moreover, the pharaohs of Dynasties 18-19 (ca. 1550-1186 BCE) are sometimes depicted with ram’s horns wrapped around their ears, with the tips of the horns curling down to rest along their cheeks or jawlines, apparently signaling thereby their divine or semi-divine status (figs. 8-9).[22]

|

|

Problems with the Horned Approach

The iconographic evidence lends support to the notion that Exodus 34 may conceive of Moses having horns, not simply shining. Additional details in the passage challenge such a conclusion, however.

If Exodus 34 imagined Moses having horns, why not place them on his “head” (rʾš), which is where they appear in ancient Near Eastern iconography (and also in medieval art)? Instead, the Hebrew text repeats three times that it is Moses’ face—not his head—that was qāran-ed. Moreover, the text states that it was the skin (עור) of his face that was qāran-ed.[23] Such a description strikes one as dissonant with the image of sprouting horns.

And yet, the Egyptian iconographic evidence does allow for a connection between horns and the face. The horns in figs. 8-9 appear precisely on the face, running from the temples to the cheeks or jawline of the pharaoh, touching, or so it would seem, “the skin of his face.” They may even have been considered part of the pharaoh’s visage. Perhaps this is what Exodus 34 is envisioning—actual horns that sprout from the head but nevertheless also touch the skin of the face somehow.

Tough Skin?

Rejecting both the shiny and horned interpretations, William H. C. Propp, in his Anchor Bible commentary on Exodus, suggests that the textual emphasis on Moses’ skin means that his face became dry or hardened in some fashion. Moses’ face becoming disfigured in his conversations with God could be an example, he argues, “of a symbolic wound incurred during a rite of passage.”[24]

Though novel, and correctly attuned to the text’s threefold emphasis on “skin,” Propp’s interpretation is not entirely convincing. Instead of Propp’s understanding of Moses’ potentially grotesque visage, the passage seems to imply something awe-inspiring and other-worldly, something that caused the Israelites fear and/or awe. Both the traditional Jewish interpretation of glowing, or the god-like interpretation of sprouting horns, seems to fit the context better.

Tying the Two Interpretations Together

In his commentary on the Torah (ad loc.), Rashi (Rabbi Solomon Yitzhaki 1040–1105) connects both options: the horned and the shining:

לשון קרנים, שהאור מבהיק ובולט כמין קרן.

[The word qāran] is related to the term “horns,” since the light was shining and projecting in the form of a horn.[25]

Rashi here intuits a connection between qāran as “horned” and qāran as “shining.” This is supported with what we know from ancient Near Eastern divine imagery, according to which the gods who wore horns on their heads were often associated with supernatural light.[26]

The Mesopotamian concept of melammu refers to a brilliant light that radiated from the gods, particularly from their heads (see, e.g., Enuma Elish IV 58). Divine weaponry, among other items belonging to the gods, could also radiate melammu. The gods were able to give melammu to others, especially monarchs, and they could also take melammu away.[27]

Melammu was often combined with the term pulḫu, the “fear” or “awe” that was evoked by powerful entities like deities and rulers.[28] This may stand behind the poetry in Habakkuk 3:4 referenced above, according to which light and horns (horns of light?) are associated with YHWH, though that passage remains difficult.

Why Would Moses Be Qāran-ed?

Whether shining or horned—or in a synthesizing interpretation: horned with light or shining because horned—the fact that Moses’ face was qāran-ed underscores his close encounter with the deity; an interaction so close that God’s divine qualities are, as it were, quite literally rubbing off on Moses and becoming physically manifested in him.

As Exodus makes clear, Moses’ face looks this way “because he had been talking with him (YHWH)” (34:29).[29] Moses has been “exposed” to YHWH in extremely close quarters—and for extended periods of time (see 34:28)—and so is now taking on godly characteristics himself.[30] No wonder the people are said to be afraid of him (34:30)![31]

The change to Moses’ face may just be what was thought to happen in prolonged divine-human encounters, or perhaps readers are to understand it to be a divine gift of some sort, like the melammu given by the gods. What is clear, regardless, is that, unlike Naram-Sin, Moses does not boast or even take pride in his new divine-like status. He is, instead, characteristically humble.[32] In fact, the text clearly states that Moses had no idea that his face looked like this (v. 29).

Indeed, once he becomes aware of how his visage frightens the Israelites, Moses takes steps to remediate it. He calls the people over to him and delivers God’s message, after which he puts on a veil:

שמות לד:לג וַיְכַל מֹשֶׁה מִדַּבֵּר אִתָּם וַיִּתֵּן עַל פָּנָיו מַסְוֶה.

Exod 34:33 When Moses had finished speaking with them, he put a veil on his face.

The veil somehow alleviates their fear, though Moses removes the veil whenever he speaks with YHWH (v. 34), and puts it back on when he relays YHWH’s message to the people (vv. 34–35). The text is not clear as to why this practice is effective, but we see from earlier texts in Exodus that to look on God—and also, or so it would seem, God’s god-like representative—is dangerous (Exod 3:6; 33:20, 23; but cf. 24:10). The use of the veil thus connects Moses’ qāran-ed face once again with the divine realm and qualities of divinity.

Behaving Like God

Despite his fear-inducing appearance, Moses must deliver God’s message to the people, which he does:

שמות לד:לא וַיִּקְרָא אֲלֵהֶם מֹשֶׁה וַיָּשֻׁבוּ אֵלָיו אַהֲרֹן וְכָל הַנְּשִׂאִים בָּעֵדָה וַיְדַבֵּר מֹשֶׁה אֲלֵהֶם. לד:לב וְאַחֲרֵי כֵן נִגְּשׁוּ כָּל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיְצַוֵּם אֵת כָּל אֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר יְ־הוָה אִתּוֹ בְּהַר סִינָי.

Exod 34:31 Moses called to them; and Aaron and all the leaders of the congregation returned to him, and Moses spoke with them. 34:32 Afterward all the Israelites came near, and he commanded them all that YHWH had spoken with him on Mount Sinai.

The way Moses relates to the people, and their response to him after he was qāran-ed is reminiscent of accounts earlier in Exodus where God interacts with Moses and the Israelites in much the same way, with the same key terms:

- ק.ר.א—God calls to Moses and the Israelites in 19:3, 20; 24:16; 31:2; 33:19; 34:5–6; 35:30;

- ש.ו.ב—The people or its leaders return to God in 19:8; 32:31;

- ד.ב.ר—God speaks to Moses and Israel in 19:8-9; 20:1, 22; 25:1; 29:42;

- נ.ג.ש—The Israelites come near to God in 19:22; 20:21; 21:6; 28:43; 30:20;

- צ.ו.ה—God commands the Israelites in 19:7; 23:15, 22; 29:35; 31:6; 34:4, 11, 18.

Such echoes are likely intentional: Moses has taken on a divine quality after all! Not surprisingly, therefore, his face, like God’s, is best left unseen (see above). Just as Moses serves as a mediator between YHWH and the people when they express their fear of hearing the divine voice (20:18–21), Moses again recognizes the need to protect Israel from the divine, this time by using the veil.[33]

Is Moses Too God-Like?

That Moses’ qāran-ed face requires veiling signifies his elevated status. To quote Leon Kass, Moses, it would seem, “has become a godlike figure, towering above the people, an object of awe and reverence.”[34] In fact, in one pseudepigraphic text, the second-century B.C.E. drama called Exagōgē (“Leading Out”) by Ezekiel the Tragedian, Moses assumes the very throne of God, takes God’s scepter, and wears God’s crown:

I [Moses] made approach and stood before the throne.

He [God] handed o’er the scepter and he bade

me mount the throne, and gave to me the crown;

then he himself withdrew from off the throne.

I gazed upon the whole earth round about;

things under it, and high above the skies.

Then at my feet a multitude of stars

fell down, and I their number reckoned up.

They passed by me like arméd ranks of men. (lines 73-81)[35]

Yet such a presentation is surely extreme and not the best reading of what happens with (and to) Moses in the rest of Exodus (and the Torah) after chapter 34.

Redirection toward God: The Tabernacle

As Kass rightly notes, “Moses will immediately use his elevated status to build the Tabernacle, to redirect the people’s awe and reverence to the Lord”[36]—not himself—a wise move in light of the people’s history in Egypt under despotic pharaohs, whose powers were god-like. It is also a wise move given what takes place at Sinai, both with the Decalogue and the punishment for the Golden Calf, where YHWH makes it clear that he will brook no rivals (20:3–6; 32:7-10).[37] A further wisdom here is that the Tabernacle can function as a place of divine-human mediation even when Moses is gone.[38]

And yet, given what transpires with (and to) Moses in Exodus 34, subsequent traditions that exalt Moses, even to the highest, are not entirely unrelated to this curious text that says his face shone—or was horned—like the very God(s) and like the very god-kings. In point of fact, Moses’ qāran-ed face may lay at the very root of those later interpretive traditions.

Coda

It is highly ironic, and profoundly unfortunate, that the remarkably positive notion that Moses’ face was qāran-ed was received, later, by some Christians, in anti-Semitic ways.[39] In this later context and reception, Moses’ horns were seen as somehow demonic if not downright devilish.

But even the most cursory look at the ancient context—the material remains of antiquity, especially art—demonstrates that nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the truth is precisely to the contrary. Looking at ancient Near Eastern iconography helps us to see the text afresh and “in a new light”—and we might add in this case—also to see it aright.[40]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 10, 2021

|

Last Updated

February 2, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Brent A. Strawn is Professor of Old Testament and Professor of Law at Duke University and a Senior Fellow in the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University where he previously served as W. R. Cannon Distinguished Professor of Old Testament. He holds an M.Div and Ph.D. from Princeton University, and is an ordained elder in the North Georgia Conference of The United Methodist Church. Strawn is the author of: What Is Stronger than a Lion? Leonine Image and Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East (2005), The Old Testament Is Dying: A Diagnosis and Recommended Treatment (2017), The Old Testament: A Concise Introduction (2020), and Lies My Preacher Told Me: An Honest Look at the Old Testament (2021). He served as both translator and member of the editorial board for The Common English Bible and has edited over twenty five volumes to date, including The Bible and the Pursuit of Happiness: What the Old and New Testaments Teach Us about the Good Life (2012), The World around the Old Testament (2014), and the award-winning The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Law (2015).

Essays on Related Topics: