Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Navigating the Torah’s Rough Narrative Terrain into the Land

Torah scroll Eisenstadt (Austria) in the Jewish Museum, Wikimedia

Parashat Chukat (Numbers 19:1–22:1) narrates a pivotal transition in the story of Israel’s journey from Egypt to the Promised Land. There is still much more narrative ground to cover before the Israelites finally end their wilderness sojourn, but the shift begins here, as the Israelites start to navigate their way into the land.

This leg of the journey is the focus of Numbers 21, a notoriously difficult text. Half of it is a travel itinerary, as engaging to read as a receipt, and it is not always clear where the Israelites are or which direction they are going. The narrative terrain is as bumpy for us as readers as we might imagine the physical terrain to have been for the Israelites. But navigating this challenging landscape yields rich results.

Into the Promised Land or Away from It?

As Numbers 21 begins, the Israelites successfully enter Canaan from the south (verses 1–3). The campaign initially meets with a setback, as the king of Arad captures some Israelites. But the Israelites vow that they will utterly destroy the Canaanite towns if God helps them win.

במדבר כא:א וַיִּשְׁמַע הַכְּנַעֲנִי מֶלֶךְ עֲרָד יֹשֵׁב הַנֶּגֶב כִּי בָּא יִשְׂרָאֵל דֶּרֶךְ הָאֲתָרִים וַיִּלָּחֶם בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל וַיִּשְׁבְּ מִמֶּנּוּ שֶׁבִי. כא:בוַיִּדַּר יִשְׂרָאֵל נֶדֶר לַי־הוָה וַיֹּאמַר אִם נָתֹן תִּתֵּן אֶת הָעָם הַזֶּה בְּיָדִי וְהַחֲרַמְתִּי אֶת עָרֵיהֶם. כא:ג וַיִּשְׁמַע יְ־הוָה בְּקוֹל יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיִּתֵּן אֶת הַכְּנַעֲנִי וַיַּחֲרֵם אֶתְהֶם וְאֶת עָרֵיהֶם וַיִּקְרָא שֵׁם הַמָּקוֹם חָרְמָה.

Num 21:1 When the Canaanite, king of Arad, who dwelt in the Negev, learned that Israel was coming by the way of Atharim, he engaged Israel in battle and took some of them captive. 21:2 Then Israel made a vow to YHWH and said, “If You deliver this people into our hand, we will proscribe their towns.” 21:3 YHWH heeded Israel’s plea and delivered up the Canaanites; and they and their cities were proscribed. So that place was named Hormah.

The term used for this vow is herem, which refers to the idea that an item, a person, or a place is dedicated to a deity. When a place is dedicated, it is to be burned down and no one left alive (Deut 20:10–18; Josh 6:15–7:26).[1] God accepts their proposal, and the terms of their vow become an etiology for the name of the place: Hormah.

Herem applies only to places that are part of the land promised to Israel by God. This detail of the story—together with two others: the enemy is a Canaanite, and the battle appears to be set in the Negev—implies that the Israelites have now entered the Promised Land.[2] We might expect the narrative to have them travel north and continue the conquest. But something different happens in the next verse:

במדבר כא:ד וַיִּסְעוּ מֵהֹר הָהָר דֶּרֶךְ יַם סוּף לִסְבֹב אֶת אֶרֶץ אֱדוֹם

Num 21:4 They set out from Mount Hor by way of Yam Suph to skirt the land of Edom.

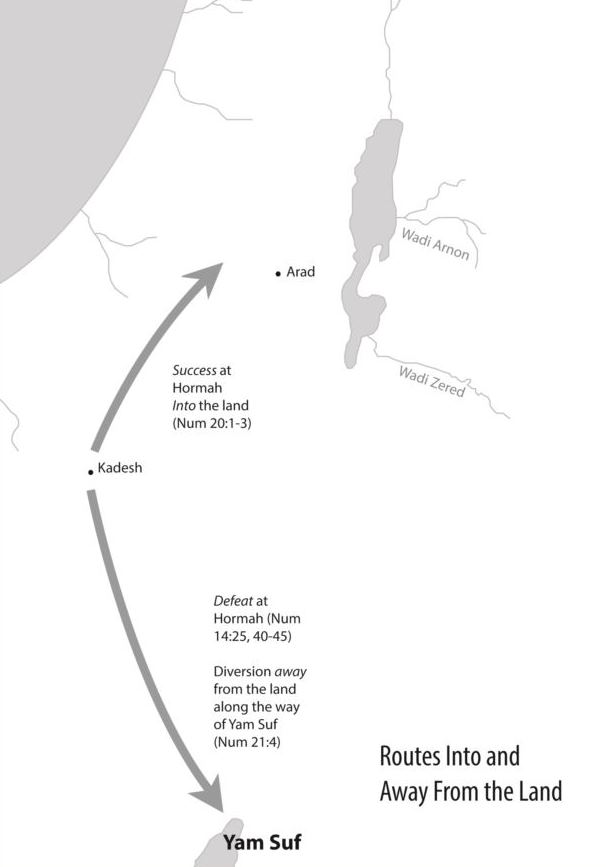

This itinerary notice has the Israelites depart from Mount Hor, the site of Aaron’s death in the episode immediately prior (20:22–29), as though the battle with the king of Arad never happened. What’s more, they travel along the western edge of Edom toward the Gulf of Aqaba (Eilat), the eastern arm of the Red Sea—away from the Promised Land rather than into it.[3] This development generates several questions: Do the Israelites enter the promised land from the south or from the east? Do they enter it now or later? We are left with the challenge of how to navigate these conflicting perspectives.

One option is to privilege one perspective over the other, and the text in its current form helps us do that. It is fairly easy to ignore the little conquest from the south in Num 21:1–3 because conquest from the east later on is so dominant—and not only because the books of Deuteronomy and Joshua are devoted to it.

The itinerary notice in Num 21:4 recalls the Israelites’ unsuccessful request for passage through Edom (20:14–21) and evokes God’s command back in the scouts episode (14:25) to follow this same route south toward the Red Sea, away from the land and deeper into the wilderness.[4]

במדבר יד:כה הָעֲמָלֵקִי וְהַכְּנַעֲנִי יוֹשֵׁב בָּעֵמֶק מָחָר פְּנוּ וּסְעוּ לָכֶם הַמִּדְבָּר דֶּרֶךְ יַם סוּף.

Num 14:25 “Now the Amalekites and the Canaanites occupy the valleys. Start out, then, tomorrow and march into the wilderness by way of Yam Suph.”

The allusion to the scouts episode also draws our attention to the fact that it ends with a briefly narrated foray into the land and battle at Hormah (14:39–45) like the one here in 21:1–3. But the one in the scouts episode ends in defeat.

במדבר יד:מד וַיַּעְפִּלוּ לַעֲלוֹת אֶל רֹאשׁ הָהָר וַאֲרוֹן בְּרִית יְ־הוָה וּמֹשֶׁה לֹא מָשׁוּ מִקֶּרֶב הַמַּחֲנֶה.יד:מה וַיֵּרֶד הָעֲמָלֵקִי וְהַכְּנַעֲנִי הַיֹּשֵׁב בָּהָר הַהוּא וַיַּכּוּם וַיַּכְּתוּם עַד הַחָרְמָה.

Num 14:44 Yet defiantly they marched toward the crest of the hill country, though neither YHWHs Ark of the Covenant nor Moses stirred from the camp. 14:45 And the Amalekites and the Canaanites who dwelt in that hill country came down and dealt them a shattering blow at Hormah.[5]

All of these texts draw our focus away from 21:1–3 and its image of Israelites successfully conquering the Promised Land from the south, and they create the impression that the Israelites have failed at any such attempt.

The episode that comes next (21:5–9) strengthens our image of Israelites going away from the land because it has Moses fashion a copper serpent to cure the snakebites the Israelites suffer as punishment for complaining; the area around Edom was well known for copper production and offers a plausible setting for just such a story.[6]

But if we are merely supposed to ignore the successful conquest of Canaan from the south in 21:1–3, why is it still there?

Torah as Conversation

The go-to answer to the question of why the Torah contains conflicting narratives—whether the conflict is due to the combination of once-independent sources or to revision—is because they were considered authoritative. The scribes had no choice but to preserve them, and they have been forced into conversation with one another only as a result of the preservation impulse. One implication of this answer is that the literary history of the Torah is an antiquarian issue. It is certainly important for those who are interested in questions of the text as artifact: how old it is, how it changed over time. Yet the relevance of literary history for readers who want to understand what the text means and how they might respond to it is not always so clear.

But several ancient texts exist independently of and can be read without having to confront their alternatives. Jubilees, for example, contains many individuals and stories also found in the Torah—Noah and the flood, Moses and the Decalogue—but it has its own distinctive focus; in particular, it adopts a 364-day solar calendar and divides history in a series of 49-year periods, or jubilees, a different way of marking time than we find in the Torah.

Furthermore, scribes sometimes omitted material from texts they revised directly, which indicates that preservation was not necessarily required.[7] While we may not want to write off authority as one factor in the literary history of the Torah, the scribes had a choice about whether or not to preserve material.

Perhaps, then, the presence of a conversation between conflicting perspectives is more than just a side effect of preservation. We might entertain the possibility that the scribes allowed multiple perspectives to stand so that we might witness the conversation among them.

Through Transjordan or Around It?

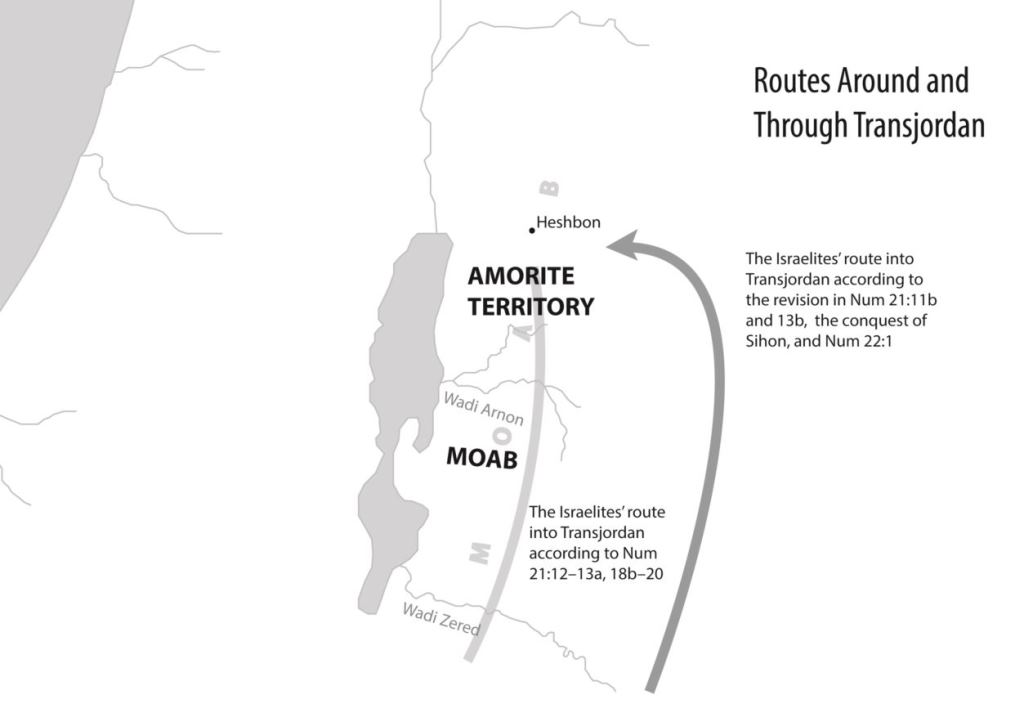

The next step of the Israelites’ journey through Transjordan takes them into Moab (21:10–20).[8] The geography implied in this route—that the Israelites will get to the Promised Land only after they cross the Jordan from the east—is reinforced in the Moabite setting of the Balaam narrative (22:3–24:25) and the introduction to Deuteronomy, according to which the Israelites are forbidden to conquer territory in Transjordan because God has given it to the descendants of Lot (Deut 2:1–24a). Yet Numbers 21 goes on to narrate the conquest of ostensibly Moabite territory in the Transjordan from Sihon (verses 21–32). Here the narrative landscape gets very difficult to navigate.

Maps in Bible atlases usually tuck Sihon’s Amorite territory alongside the Dead Sea and the Jordan River, relegating Ammon—like Moab, territory given to the descendants of Lot—out toward the eastern wilderness.[9] This picture is the result of a strictly horizontal reading of Numbers 21: The Israelites cross Zered and Arnon Streams in verses 12–13a, then they travel through the places listed in verses 16–20 until they arrive in in “the valley that is in the country of Moab, at the peak of Pisgah, overlooking the wasteland” (Num 21:20; הַגַּיְא אֲשֶׁר בִּשְׂדֵה מוֹאָב רֹאשׁ הַפִּסְגָּה וְנִשְׁקָפָה עַל פְּנֵי הַיְשִׁימֹן). Only then do they conquer Sihon’s territory in verses 21–32, after which they conquer more territory farther north from Og (verses 33–35) before they finally wind up back in Moab at the beginning of chapter 22.

במדבר כב:א וַיִּסְעוּ בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיַּחֲנוּ בְּעַרְבוֹת מוֹאָב מֵעֵבֶר לְיַרְדֵּן יְרֵחוֹ.

Num 22:1 The Israelites then marched on and encamped in the steppes of Moab, across the Jordan from Jericho.

Reading this text as though these are all elements of a single coherent picture gets the Israelites where they need to be for the Moabite setting of the Balaam narrative and Deuteronomy and accounts for the conquest of territory from Sihon and Og. But it flattens some rather challenging narrative terrain in the process.

Rough Narrative Terrain

The narrative landscape of this text contains several significant bumps. The Israelites arrive in Moab in Numbers 21:20 and then arrive there again in 22:1, suggesting that this itinerary may not be as linear as it seems. It is clear what happens in the interim—they conquer Sihon and Og—but it is not clear where they go. Verse 20 has the Israelites camped at Pisgah, near the Jordan River. But they are suddenly in the wilderness east of settled territory in Transjordan when they request passage through Sihon’s territory.

במדבר כא:כא וַיִּשְׁלַח יִשְׂרָאֵל מַלְאָכִים אֶל סִיחֹן מֶלֶךְ הָאֱמֹרִי לֵאמֹר. כא:כבאֶעְבְּרָה בְאַרְצֶךָ …. כא:כג וְלֹא נָתַן סִיחֹן אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל עֲבֹר בִּגְבֻלוֹ וַיֶּאֱסֹף סִיחֹן אֶת כָּל עַמּוֹ וַיֵּצֵא לִקְרַאת יִשְׂרָאֵלהַמִּדְבָּרָה וַיָּבֹא יָהְצָה וַיִּלָּחֶם בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל.כא:כד וַיַּכֵּהוּ יִשְׂרָאֵל לְפִי חָרֶב וַיִּירַשׁ אֶת אַרְצוֹ מֵאַרְנֹן עַד יַבֹּק עַד בְּנֵי עַמּוֹן…

Num 21:21 Israel now sent messengers to Sihon king of the Amorites, saying, 21:22 “Let me pass through your country….” 21:23 But Sihon would not let Israel pass through his territory. Sihon gathered all his people and went out against Israel in the wilderness. He came to Yahatz and engaged Israel in battle. 21:24 But Israel put them to the sword, and took possession of their land, from the Arnon to the Jabbok, as far as the Ammonites,

How did the Israelites get from Pisgah near the Jordan to the wilderness east of Sihon’s territory? The text does not tell us.

In fact, Pisgah poses a double problem because verse 20 explicitly locates it in Moab. Yet verse 24 defines Sihon’s Amorite territory as extending from the Arnon to the Jabbok, which would include Pisgah. Just whose territory is Pisgah in? Verses 26–30 explain this bump in historical terms by asserting that that the territory used to be Moab but was conquered by Sihon the Amorite before the Israelites ever arrived. But the Balaam narrative resists that explanation because Balak, king of Moab, walks Balaam up Pisgah (23:14). Pisgah is still conceptualized as part of Moab here.

Pisgah is not the only place in 21:20 that factors into the setting of the Balaam narrative. Balaam also ascends Bamoth(-baal) (22:41) and looks out over the wasteland (23:28) from the summit of Peor. The itinerary in Numbers 21:19–20 takes the Israelites straight into Moab in preparation for the Balaam narrative, as though the conquest of Sihon were not part of the narrative.

With the conquest of Sihon’s territory in place, however, reading Pisgah as part of Moab is a problem: Israel is not supposed to conquer Moabites. The Sihon narrative does not have this problem, because Sihon is an Amorite, and Amorites are among the peoples who live in the Promised Land. Unlike Moabites, Israel is allowed to conquer them.[10]

So, on one level, we are confronted with a geographical conflict, a classic conundrum in the interpretation of Numbers 21: Are the Israelites going through or around Transjordan? But we are also confronted with an ideological one: Is this territory Moab and forbidden for Israelites to conquer? Or is it Amorite, and permissible to conquer?

Making Room for Conquest

Making the territory between the Arnon and the Jabbok Amorite is an important step in facilitating the inclusion of a conquest narrative here. Moreover, we can see where the account of Israel travelling north has been tweaked in order to do just that:

במדבר כא:י וַיִּסְעוּ בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיַּחֲנוּ בְּאֹבֹת. כא:יא וַיִּסְעוּ מֵאֹבֹת וַיַּחֲנוּ בְּעִיֵּי הָעֲבָרִים בַּמִּדְבָּר אֲשֶׁר עַל פְּנֵי מוֹאָב מִמִּזְרַח הַשָּׁמֶשׁ. כא:יבמִשָּׁם נָסָעוּ וַיַּחֲנוּ בְּנַחַל זָרֶד. כא:יגמִשָּׁם נָסָעוּ וַיַּחֲנוּ מֵעֵבֶר אַרְנוֹן אֲשֶׁר בַּמִּדְבָּר הַיֹּצֵא מִגְּבוּל הָאֱמֹרִי כִּי אַרְנוֹן גְּבוּל מוֹאָב בֵּין מוֹאָב וּבֵין הָאֱמֹרִי.

Num 21:10 The Israelites marched on and encamped at Oboth. 21:11 They set out from Oboth and encamped at Iye-abarim, in the wilderness bordering on Moab to the east. 21:12From there they set out and encamped at the Zered Stream. 21:13 From there they set out and encamped beyond the Arnon, that is, in the wilderness that extends from the territory of the Amorites. For the Arnon is the boundary of Moab, between Moab and the Amorites.

The clauses identified in bold interfere with the basic itinerary structure of the passage. Itineraries sometimes contain such clauses, so their presence is not necessarily out of the ordinary.[11] The problem with these particular clauses is that they create an impression of the Israelites’ route and the geography of Transjordan that is at odds with what follows in verses 16–20.

The first (21:11b) seems to locate Iye-abarim east of Moab, building a picture of the Israelites out in the eastern wilderness despite the fact that verses 12–13a would seem to have them cross right over the Zered and the Arnon, as they do in the introduction to Deuteronomy in order to pass through settled territory in Moab and Ammon (Deut 2:8–24a), and verses 18b–20 would have them head straight north into Moab.[12]

The second clause (21:13b) also redefines “the other side of the Arnon” as being out in the eastern wilderness and introduces us to the area closer to the Jordan river as Amorite, not the Moabite territory it clearly is in verse 20.

In other words, one version of the story imagines the Israelites passing peacefully through Moab on the west side of the Transjordan, as they do in Deuteronomy (2:8–18), but this story has been rewritten in order to accommodate a conquest of Sihon’s Amorite territory.[13] This revision might have been possible without changing the geography to have the Israelites go around settled territory in Transjordan in order to approach Sihon from the eastern wilderness.[14] But the ideology—the idea that this territory is Moab and not permissible for Israelites to conquer—could not stand. The text had to be modified to create the impression that the Israelites avoid Moabite territory north of the Arnon, the itinerary in 21:19–20 and the setting of the Balaam narrative notwithstanding.

A Geographical Palimpsest

What we are navigating here is a geographical palimpsest.[15] A palimpsest is a text that has been erased or scratched out in order to write a new text over the top of the old one. Traces of the old text are visible under the new one, making palimpsests very challenging to read. Especially when traces of the old text are prominent, it can be difficult to tell the two apart. But there are clues, and those clues are available to every reader.[16]

Palimpsests are usually the result of recycling expensive writing material—stone, skin, papyrus. Our palimpsest in Numbers 21 exists for a different reason. One version of our text narrated a journey straight north into Moab, where the Balaam narrative is set. It involved no conquest narratives, because this territory was considered off limits, assigned by God to someone else in the introduction to Deuteronomy, also set in Moab. Territory in Transjordan is not part of the Promised Land.

It seems not everyone agreed about that because, alongside this journey into Moab we find a conquest of that same territory, where the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and (part of) Manasseh will settle later in the narrative. What was illegitimate to conquer from Moabites is now legitimate to conquer from Amorites, just like the (rest of the) Promised Land west of the Jordan.

The fact that these conflicting views are available to us in a palimpsest means that we as readers are confronted with this dynamic conversation about the extent of the Promised Land in a way that we are not when it comes to the calendrical differences between the Torah and Jubilees. But we can see this only if we read our parashah in a way that accounts for its complicated terrain. If we try to flatten that terrain into a singularly coherent narrative, minimizing geographical and ideological conflicts, we will miss it.

It is important that we do not miss it because the very presence of multiple, conflicting voices in one text draws us into the dialogical and historical landscape of the narrative as well as its plot development.[17] It asks something more of us as readers—not merely to follow one view, but to actively participate in the conversation we are allowed to witness. The very nature of the Torah as a text with a literary history we can see asks us to be a certain kind of reader—willing to be attentive to and participate in that conversation—in order to do it justice.[18]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 12, 2019

|

Last Updated

December 3, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Angela Roskop Erisman is owner of Angela Roskop Erisman Editorial and was the

founding editorial director of the Marginalia Review of Books. She earned her M.A. in

Hebrew and Northwest Semitics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and her Ph.D.

in Bible and Ancient Near East at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.

She is the author of The Wilderness Itineraries: Genre, Geography, and the Growth of

Torah (2011), for which she won a Manfred Lautenschläger Award for Theological

Promise in 2014. Her most recent book, The Wilderness Narratives in the Hebrew Bible:

Religion, Politics, and Biblical Interpretation (2025) is available from Cambridge

University Press.

Essays on Related Topics: