Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Preserving Multiple Opinions

Judges of the Supreme Court of Israel

In the beginning of Parashat Yitro (Exodus, Chapter 18) we read how Moses’s father-in-law, the Midianite priest Jethro, sees Moses sitting as a judge from morning to evening. Jethro advises Moses to delegate authority so that he not collapse under the burden of being the sole judge for the entire people. He tells Moses to hear only the difficult cases, the ones for which he would have to consult God.

For the majority of cases, for which the rules were already known, he should select men with the right character to deal with them: “capable men who fear God [that is, with a conscience], trustworthy men who spurn ill-gotten gain” (Exodus 18:21),[1] and to put them in charge of units of 1000, 100, 50 and 10 men. The fact that the officials are called by military titles — “chiefs of thousands (שרי אלפים),” “chiefs of hundreds (שרי מאות),” etc.[2] — indicates that their function would include military as well as judicial roles, which is consistent with the integration of leadership roles in ancient and tribal societies, and reflects the Torah’s depiction of the Israelites as an army on its way to conquer the promised land.[3]

Parashat Devarim tells how years later, at the end of his life, when Moses told the next generation about this event, he said that he had asked the people to select for the job “men who are wise, discerning, and experienced” (Deuteronomy 1:13).[4] According to Exodus, then, judges must be righteous people of sterling character, while Deuteronomy calls for people who possess the right intellectual qualities.

There are ways we might reconcile these differing descriptions of the qualifications that Moses sought. Perhaps, in Deuteronomy, Moses felt that the intellectual qualifications would guarantee that his appointees also held the highest ethical standards: knowing what is right would lead to doing what is right. Or perhaps Jethro and Moses actually sought people with all seven qualities, ethical and intellectual alike, and each narrative is telling us only part of what they said (the Midrash held that Jethro did recommend all seven qualities, and in fact Maimonides says that all seven are required for judges).[5]

The Documentary Hypothesis as an Explanation for Differing Accounts

Critical scholarship does not try to reconcile the different lists of qualities. In the critical view, the narratives in Exodus and Deuteronomy are from different literary sources, written by different authors who had different views about the qualities that are the sine qua non for judges. This judgment isn’t based solely on the different lists of qualities, for the two accounts also differ in other ways.

One difference is the chronological setting. In Exodus the episode is placed right before the revelation at Mount Sinai (Exodus 19-20), while in Deuteronomy it takes place almost a year later, as the people are about to leave Sinai and head for the promised land. Additionally, in Deuteronomy Moses does not mention Jethro’s suggestion to him but proposes the idea to the people on his own. In Exodus Jethro advises Moses to choose men “from among all the people (מכל העם)” (Exod. 18:21), but in Deuteronomy Moses chooses “the tribal leaders (ראשי שבטיכם)” (Deut. 1:15). All of these differences add up to the impression that different authors wrote the two versions of the episode.

This is a good example of the kinds of inconsistencies that led to the development of the Documentary Hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, the Torah was compiled from several documents that covered roughly the same ground. Scholars refer to these original documents as J, E, P and D.[6] Over time these four documents were spliced together by compilers known as redactors. [7] For the sake of simplicity, scholars often speak of a single Redactor, abbreviated as R.

Each document presented the narratives and laws and other materials of the Torah in its own style and from its own point of view. When the redactors brought alternative versions together, they sometimes interleaved them into a single running narrative (as in the case of the flood story in Genesis 6-9) and sometimes left them separate, either placing them next to each other (as in the case of the two successive creation stories in Genesis 1 and 2) or at a distance from each other (as in the present case of Moses appointing his subordinates).

Whichever method they followed in any particular case, the redactors incorporated the sources with minimal omissions and revisions, rather than choosing one version over another or rewriting them to produce a single, smooth narrative. Their methods often produced repetition of episodes and contradictory accounts of the same events and laws, a result they apparently tolerated because it enabled them to remain true to their sources.[8]

Judicial Qualifications According to E and D

According to the Documentary Hypothesis, the account in Exodus is from the E source, dated roughly to the late 10th-late 8th centuries BCE,[9] while Deuteronomy was composed later, in the seventh century BCE.

Deuteronomy reflects the views of a scribal school that was strongly influenced by Wisdom Literature, the chief representative of which is the book of Proverbs.[10] This literature strongly emphasizes intellectual values. Under its influence, Deuteronomy is the first book to depict Moses as not just communicating the laws to the people but expounding (באר) them (1:5) and teaching (מלמד) the people (4:1), and it is the first book to require parents to teach(ושננתם, ולמדתם) their children about God and his laws (6:7; 9:19), and the first to ordain a public reading of the Torah for the same purpose (31:10-13).

Deuteronomy requires the king to make a personal copy of the book to study (17:18-19). It tells the people that obeying God’s laws will be proof of their wisdom and discernment in the eyes of other nations (4:6). It emphasizes wisdom when it rephrases passages from the other books of the Torah: when Moses ordains Joshua to succeed him he imbues Joshua with wisdom (רוח חכמה) (34:9), whereas its source in Num. 27:18-20 says he imbued him with authority (הוד); according to Deut. 16:19 judges must reject bribes because “bribes blind the eyes of the discerning” (literally, “the wise”),[11] whereas Exod. 23:8 says that “bribes blind the clear-sighted.”[12]

This aspect of Deuteronomy reflects a viewpoint that places a premium on cultivating the intellect, whereas the E source emphasizes qualities of character. This is a matter of emphasis; there is no reason to believe that either source would wish to negate the other.

Preserving Multiple Versions in Later Jewish Sources

In keeping with his method, in presenting two separate accounts of how Moses appointed his subordinates, the redactor who joined Deuteronomy to the preceding sources made no attempt to choose between the accounts or rewrite them to smooth out the contradictions, even if he may have reconciled them in his own mind. This presented a challenge that was taken up by later commentators, as in the midrash that held that Moses actually required all seven qualities. But the redactor was more interested in preserving the differences than in reconciling them.

Similarly, Jewish religious authorities in postbiblical times sometimes encountered multiple views of how a prayer should be worded or a practice should be followed. Talmudic literature records a number of cases in which our liturgy has combined different versions of the same prayer. The best known example is found in the Passover Haggadah, which contains two different answers to the Four Questions: Avadim hayyinu (“We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt”), and Miteḥillah ovdei avodah zarah hayu avoteinu (“At first our ancestors were idol-worshippers”). These are actually the different answers suggested by two different Talmudic authorities of the third century, Samuel and Rav.[13] Confronted with these two different suggestions, the early post-Talmudic authorities ruled that “we practice in accordance with both,” and since that time the Passover Haggadah has included both answers.[14] In this case and others like it, two or more rabbis prescribed their own version of a prayer,[15] and the Talmud decides “Therefore we will say both, or all, of them.”[16]

Another example of this approach concerns tefillin. There are two main views of the order in which the biblical passages written on parchment strips inside the tefillin should be arranged, the views commonly identified with Rashi and Rabbenu Tam. Some particularly pious individuals wear two sets of tefillin, one in accordance with each view (wearing them either simultaneously or for different parts of the morning prayers) in order to fulfill the commandment with whichever is halakhically correct.[17]

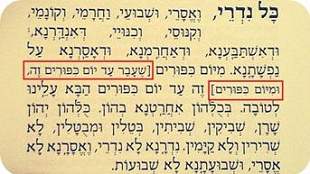

The thinking behind some of these decisions may be the same thinking that was expressed by Rabbi Jacob Emden (1697–1776) in his decision about the wording of Kol Nidrei. Some versions of Kol Nidrei nullify vows made during the past year, while others, in agreement with the position of the great legal authority Rabbenu Tam (ca. 1100–1171), nullify vows that will be made during the coming year (this is the version that Ashkenazim use today). Emden was certain that the original version referred to vows made in the past, but he decided to approve a text that combines both versions, nullifying vows of both the past year and the coming year, and this practice is followed by many Sephardic and Middle Eastern communities to this day.[18] His reason, he explained, is out of reverence for the view of Rabbenu Tam, “since it came from the mouth of that saintly man.”[19]

One reason for preserving both versions of a text, then, may be out of reverence for their authors. Another possibility is that the redactors considered all the sources they preserved as authoritative or valid, perhaps even as sacred, presuming that “these and those are the words of the living God.” This phrase, in which the Talmud sometimes characterizes conflicting opinions of different sages,[20] is certainly applicable as well to what seems to be the biblical redactors’ evaluation of their sources.

The redactors’ commitment to presenting multiple versions “as is” admittedly produces confusion about what exactly happened in the past and, in cases of contradictory laws, exactly what to do. Eventually this forced commentators to adopt non-literal, midrashic methods of interpretation to reconcile inconsistencies. These methods had a beneficial effect, fostering a kind of “loose constructionism” that enabled Jewish law and theology to adapt to changing ideas and societal needs, such as construing “an eye for an eye” (Exodus 21:24-25 and elsewhere) more humanely to mean monetary compensation for injuries and accommodating the creation story in Genesis 1 to philosophical and scientific ideas of cosmology.

The Impulse to Preserve Multiple Versions

Apart from the long-range effects of the redactors’ method, our interest here is in their very commitment to preserving multiple versions. They implicitly recognized that no single version of the past and no single tradition or practice necessarily preserves or expresses the whole truth; the truth comes from recognizing the potential validity of different viewpoints. Taking the redactors’ approach seriously means recognizing that they were not simply compilers gathering up the work of others, but religious thinkers in their own right.[21]

The first person to point this out was the Jewish theologian Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929). He expressed a view of revelation that combined faith with criticism:

…[F]rom our[22] belief in the sanctity, i.e. the uniqueness of the Torah and in its revelational character we cannot draw any conclusions concerning its literary genesis… [I]f all of Wellhausen’s[23] theories were right… this would not in the least affect our belief… We, too, translate the Torah as a single book; to us, too, it is the work of one spirit. We do not know who he was; that it was Moses we cannot believe. Among ourselves we identify him by the siglum used by critical scholarship for its assumed final redactor: R. But we fill out this R not as Redactor but as rabbenu [our Teacher].[24]

Rosenzweig stressed that what counts is the final product produced by the Redactor:

For, whoever he was and whatever material he had at his disposal, he is our Teacher, his theology is our Teaching. For example: even if criticism should be right and it were true that Genesis 1 and 2 really stemmed from distinct authors…even then, what we must know about creation is not to be got out of one of the two chapters alone, but only out of taking them together and harmonized — and from the harmonization precisely of their apparent contradictions from which critical analysis starts: namely the “cosmological” creation leading to man of the first chapter and the “anthropological” creation beginning with man of the second. Only this … is the Teaching.[25]

Rosenzweig argues that the truth comes from considering multiple points of view. With respect to the qualifications of judges this is an easily applied lesson, since both intellectual and ethical qualities are clearly desirable and compatible. But the deeper lesson lies in the Redactor’s challenge to us to recognize that there is at least partial truth, or partial value, in more than one option, to embrace differences, to find ways to combine or harmonize them when possible and respect them when it is not. In our polarized time, this is a lesson to take to heart.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

January 13, 2014

|

Last Updated

February 6, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi Jeffrey Tigay is Emeritus Ellis Professor of Hebrew and Semitic Languages and Literatures at the University of Pennsylvania. He has his Ph.D. from Yale, and his M.H.L and ordination from JTS. He is the author of the Jewish Study Bible commentary on Exodus and the JPS commentary on Deuteronomy, a revised Hebrew edition of which will be published in the Mikra LeYisrael series. He is currently writing a commentary on Exodus for the same series.

Essays on Related Topics: