Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Retelling the Story of Moses at Dura Europos Synagogue

Dura Europos Synagogue: Western Wall (Yale Univ. Art Gallery – Cuny.edu)

The Discovery of Dura Europos

Like a Near Eastern sleeping beauty, the city of Dura Europos had been lying undisturbed, covered by a layered blanket of sand, for 1700 years. The site, which can be found in modern day Syria on its border with Iraq, was discovered by sheer accident in 1920, when a group of British soldiers bivouacked in a ruined desert fortress overlooking the Euphrates.[1] To their surprise, their efforts at camouflaging unearthed ancient wall paintings in a wonderful state of preservation. The paintings are so remarkable, it is sometimes called the Syrian Pompeii.[2]

They duly reported the find, adding that these should be seen by an expert. There was indeed an expert available, none other than the great American orientalist James Henry Breasted (1865–1935), who happened to be in the area busy with his own survey. Breasted spent a single day at Dura. The outcome was an entire volume, published in 1922, the spearhead of both many excavations and countless publications focusing on the site.[3]

A Brief History of Dura Europos

The modern name Dura Europos reflects the fortress-town’s double heritage. Dura, a Semitic word meaning “dwelling, enclosure, or fort,” was the name used by the town’s Aramaic speaking population. Europos was the name bestowed by the Greek-Macedonian general, Seleucus I Nicator, who founded it, naming it after his birthplace, a Macedonian city of that name. (In ancient times it was called one or the other.)

In a history that spans some five centuries, Dura Europos changed several hands between several empires, not an uncommon destiny of strategic locations along a contested zone.

Seleucid Greek—Established around 300 B.C.E. by Macedonian forces under Seleucus I Nicator, Dura Europos was settled by remnant of the Macedonian armies commanded by Alexander the Great together with local Arameans, and was ruled by the Seleucids for nearly two centuries.[4]

Parthian—Between 113 B.C.E. and 165 C.E., Dura was under Parthian rule,[5] a prolific period that witnessed the construction of numerous temples to various Semitic deities.[6]

Roman—In 165 C.E., the Romans under Emperor Lucius Varus, conquered the area near the Euphrates, and the city became home to a Roman garrison, which defended this area as the new eastern border of the Empire.[7]

Sassanian-Persian—In 256 C.E., after barely a century of Roman control, Dura Europos was conquered by the rising Sassanian empire. It was abandoned, never to be settled again.

Isolated for almost Two Millennia

Dura Europos sits on the bank of the Euphrates yet is inaccessible from the river and solely by land. Approaching the town would have entailed crossing an arid territory without ready means of sustaining an army. After its conquest by the Sasanid-Persians, the town was abandoned, and remained uninhabited until modern times. The sands of the desert covered it so effectively that only an incidental trench digging during WWI revealed a corner of it.[8]

Many structures, including the earliest known Christian baptistery (a small building used for baptisms), were found at Dura. The excavations also revealed countless wall paintings, ordinarily an art that time does not treat kindly, in different architectural contexts. In addition, a variety texts in Greek, Latin, Aramaic, Parthian, and Middle Persian and on a variety of media shed precious light on the inhabitants of this city—soldiers and civilians. Different groups had their own sanctuaries and rituals. By far, the most significant discovery was that of the synagogue.[9]

The Synagogue of Dura Europos

We have no idea when Jews first settled in the area, and in general, know very little about the Jewish community there. They may have arrived with the Roman garrison but we do not know whence they had hailed. Their presence, however, is well attested through the community’s spectacular synagogue.

When it was remodeled in 245 C.E., a mere decade before the city succumbed to the Sassanians, the synagogue’s walls were decorated with paintings of biblical scenes.[10] These include Ezekiel’s famed vision of the valley of the dry bones; the ark of the covenant in the land of the Philistines; the tribes of Israel around the well of Miriam; Elijah and the prophets of the Baal; a battle scene (between the Israelites and the Philistines?); and Jacob’s dream—in brief, an astonishing and tantalizing selection that continues to bedevil contemporary scholarship.

None of these scenes are labelled. Thus, while the interpretation of several panels is fairly secure, that of others is open to speculations. Above all, there is no agreement regarding the overall message or agenda of the paintings nor the Judaism practiced in this remote spot on the Euphrates.[11]

The synagogue is unique. No other Diaspora synagogue has delivered such a full program of biblical images. No other synagogue around the entire ancient Mediterranean contains such an array of paintings, not even the pictorial mosaics that decorated the floors of synagogues in Roman Palestine, such as the synagogue in Huqoq. We know of no other Jewish community that encouraged, to the same extent, synagogue attendees not only to listen but also to feast their eyes on biblical stories.

The Lowest Register: A Children’s Section?

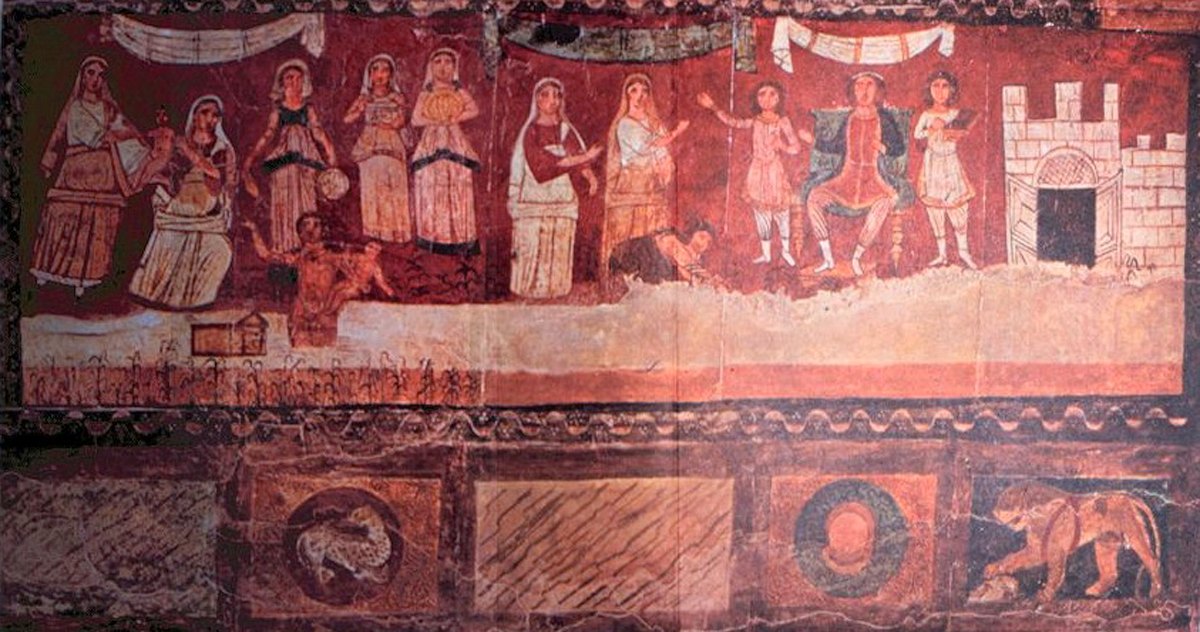

Especially intriguing is the lowest register of the western wall—the wall facing Jerusalem, where the ark was placed and where the people faced during prayers—which was created to educate children.[12] The “children register” contains four scenes featuring children at different stages of life, from babyhood to early adulthood.

The western wall also contains a panel depicting Elijah’s miraculous revival of the widow’s child; one showing Samuel anointing the patently adolescent David; a very large one showing Moses’ infancy; and another depicting Esther at the Persian court. The latter was so fetching that occasionally visitors scribbled graffiti on it with their name, date of visit, and how much they liked these paintings.

The Rescue of Baby Moses: Parsing the Panel

If you were a child in this synagogue, say around 250 CE or 1769 years ago, you would have no doubt recognized the story behind the panel below based on the first two chapters of Exodus. We will read this panel from right to left, as Hebrew and Aramaic are read.

Pharaoh Commands the Midwives to Kill the Boys

The picture begins at the palace, with the Pharaoh seated on his throne. He appears to be speaking. To his left is a man, no doubt a scribe, writing down the royal commands. On the ruler’s right is another courtier pointing at two heavily clad women. There is hardly a doubt that the artist depicted the command issued to the two midwives to kill Israelite babies:

שמות א:טו וַיֹּאמֶר מֶלֶךְ מִצְרַיִם לַמְיַלְּדֹת הָעִבְרִיֹּת אֲשֶׁר שֵׁם הָאַחַת שִׁפְרָה וְשֵׁם הַשֵּׁנִית פּוּעָה. א:טז וַיֹּאמֶר בְּיַלֶּדְכֶן אֶת הָעִבְרִיּוֹת וּרְאִיתֶן עַל הָאָבְנָיִם אִם בֵּן הוּא וַהֲמִתֶּן אֹתוֹ וְאִם בַּת הִוא וָחָיָה.

Exod 1:15 The king of Egypt spoke to the Hebrew midwives, one of whom was named Shiphrah and the other Puah, 1:16 saying, “When you deliver the Hebrew women, look at the birthstool: if it is a boy, kill him; if it is a girl, let her live.”

The painter has anachronistically depicted Pharaoh’s court as a Persian-Sassanian court. This explains the presence of the courtiers, who are not depicted in the biblical text; in addition, the king is plainly wearing royal Sassanid garb.

Moses’ Mother Puts Him in the Nile

In front of the two midwives is a female figure bending over an object which has not been preserved. She must be Moses’ mother placing her baby in an ark in the Nile:

שמות ב:ג …וַתִּקַּח לוֹ תֵּבַת גֹּמֶא וַתַּחְמְרָה בַחֵמָר וּבַזָּפֶת וַתָּשֶׂם בָּהּ אֶת הַיֶּלֶד וַתָּשֶׂם בַּסּוּף עַל שְׂפַת הַיְאֹר.

Exod 2:3 …She got a wicker basket for him and caulked it with bitumen and pitch. She put the child into it and placed it among the reeds by the bank of the Nile.

Thus, we move from Pharaoh’s decree against Hebrew boys, to the effort of Moses’ mother to hide her son in rushes of the Nile to save him.[13]

Pharaoh’s Daughter Finds Baby Moses

To the left of these figures are three similarly dressed women, a mystifying trio.[14] Are these the maidens of the Egyptian princess? Perhaps the artist is depicting this verse:

שמות ב:ה וַתֵּרֶד בַּת פַּרְעֹה לִרְחֹץ עַל הַיְאֹר וְנַעֲרֹתֶיהָ הֹלְכֹת עַל יַד הַיְאֹר וַתֵּרֶא אֶת הַתֵּבָה בְּתוֹךְ הַסּוּף וַתִּשְׁלַח אֶת אֲמָתָהּ וַתִּקָּחֶהָ.

Exod 2:5 The daughter of Pharaoh came down to bathe in the Nile, while her maidens walked along the Nile. She spied the basket among the reeds and sent her slave girl to fetch it.

We cannot identify with certainty the naked woman standing in the water, holding a baby in her left arm: she may be another one of the maids, or perhaps Pharaoh’s daughter herself. The artist assumes she was naked—a detail the biblical text had no reason to narrate, but reflecting the logical assumption that people entered the river naked when going down to bathe.[15]

Miriam and Yocheved: The Midwives?

Turning to the final image, who are the two heavily clothed women on the left, holding an infant between them? They are shown as the mirror image of the midwives, as though they, too, are midwives; all the Hebrew females conform to a dress code that makes it practically impossible to distinguish among them. These two women are likely the only females connected to Moses in the Bible: his mother and his sister (both unnamed in Exodus 2 though named Yocheved and Miriam in Exodus 6).

In placing them here, the artist must have relied on traditions we know from midrashic literature, which depicts Miriam and Yocheved as the two midwives called Shiphrah and Puah Exodus 1. This is first attested in the 3rd century tannaitic midrash, Sifrei Numbers (78, Kahana ed.), which explains that Shiphrah and Puah are really nicknames:

ויאמר מלך מצרים למילדת וג’—שפרה זו יוכבד פועה זו מרים. שפרה שפרת ורבת. שפרה שהיתה משפרת את הוולד. שפרה שפרו ורבו יש[ראל] בימיה. פועה שהיתה פועה ובוכה על אחיה, שנ[אמר] ותתצב אחתו מרח[וק].

“And the king of Egypt said to the midwives, etc.”—Shiphrah is Yocheved and Puah is Miriam. [Yocheved is called] Shiphrah because she was fruitful (shepharat) and multiplied. Shiphah because she would improve (meshaperet) the newborn. Shiphrah because the Israelites were fruitful (sheparu) and multiplied in her day. [Miriam is called] Puah because she would groan and cry about her brother, as it says, “and his sister stood by at a distance” (Exod 2:4).[16]

If this identification of these two figures with Shiphrah and Puah is correct, then this midrashic motif found first in the 3rd century midrash was already widely known, even in this remote community.

The visualization of Moses’ infancy on the synagogue’s western wall provides an example of the reception of the biblical text in communities between Eretz Israel and Babylonia. Both text and its midrash must have been selected because of their direct meaning to contemporary viewers.

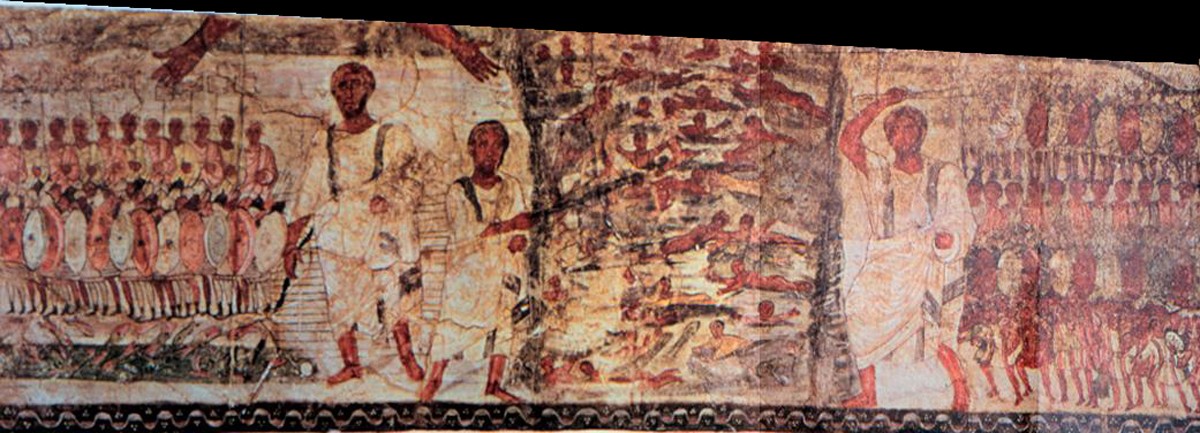

The Giant Moses of the Exodus Story

On the same western wall, the top register continues the cycle of Moses’s life, this time with the exodus itself. These unknown artists brought the exodus to life, from the hasty departure from Egypt through the crossing of the Red Sea and the drowning of the armed Egyptian pursuers. It is a very crowded picture, as though the painter tried to convey a sense of both numbers and panic.

Moses towers over the countless faceless humans, and appears no less than three times on this large panel, a solitary man whose stature is guaranteed not only by the story but also by his enormous dimensions of the image. Even the mighty walls of Egypt and the gushing Red Sea appear insignificant by comparison.

Next to the Exodus scenes that occupy half of the upper register of the painted wall, another bearded Moses, is painted, here standing next to the burning bush, upon the soil of God’s first revelation to him. All these images of Moses of the upper register face the worshipper.

Thus, Moses practically dominates the Western Wall, with no less than five panels, two enormous at the top depicting the Exodus, one showing him in the center with the burning bush, and the infancy scene. No other figure occupies so much space at Dura.

Dura Europos as an Anti-Haggadah?

Biblical interpretation is as old as the Bible itself. The desire and the need to go beyond the brevity of the biblical text generated rich exegetical literature already in antiquity, and artistic depiction of the Bible demanded even further interpretation and filling in of detail. The walls of the remote synagogue of Dura Europos show how specific interpretative strands were “translated” into visual imagery. Its images draw simultaneously on myth, memory, and midrash.

The dominance of Moses here is striking in view of his almost total absence from the Passover Haggadah, the central text of the Passover Seder. Considering how conspicuous and crucial Moses’ role is in the exodus narrative, this well-known, though strange feature of the Haggadah is difficult, if not impossible, to explain.

Perhaps the Haggadah is suggesting that God, not Moses, is the real hero of the exodus story. If so, clearly the Jews at Dura Europos on the Euphrates were unsympathetic with this message, and in stark contrast, gave Moses the most conspicuous place on the front wall of their synagogue.

We can imagine the Jewish community of Dura “correcting” this gap in the Haggadah with a striking visual amendment that dwelt on Moses. Now that the synagogue has been excavated and its images available for display, we too may feast our eyes during Passover on the person to whom the Torah ascribes extraordinary qualities of leadership and whom the ancient Jews living on the Euphrates regarded as the greatest biblical hero.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 23, 2019

|

Last Updated

February 9, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Hagith Sivan is Professor Emerita of History in the University of Kansas’ Center for Global and International Studies. She holds a Ph.D. from Columbia University, and among her many books are, Jewish Childhood in the Roman World (2018), Galla Placidia: The Last Roman Empress (2011), Between Woman, Man and God: A New Interpretation of the Ten Commandments (2004), and Dinah‘s Daughters: Gender and Judaism from the Hebrew Bible To Late Antiquity (Philadephia 2002).

Essays on Related Topics: