Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Samson the Demigod?

Samson depicted as Atlas with the earth on his shoulders. From Sefirat HaOmer (plus Mincha-Maariv) Siddur, Baruch Ben Shemaria (Amsterdam, 1795) Braginsky Collection, e-codices

Judges describes Samson as a man with superhuman attributes. At one point, he tears a full grown lion in half with his bare hands (Judg 14:5–6) and at another he kills three thousand Philistine warriors with the jawbone of a donkey (Judg 15:14–16). In a later escapade, Samson spends the night with a prostitute in Gaza while Philistine warriors are hiding on the other side of the city wall to kill him. The text describes how he escapes:

שופטים טז:ג …וַיָּקָם בַּחֲצִי הַלַּיְלָה וַיֶּאֱחֹז בְּדַלְתוֹת שַׁעַר הָעִיר וּבִשְׁתֵּי הַמְּזוּזוֹת וַיִּסָּעֵם עִם הַבְּרִיחַ וַיָּשֶׂם עַל כְּתֵפָיו וַיַּעֲלֵם אֶל רֹאשׁ הָהָר אֲשֶׁר עַל פְּנֵי חֶבְרוֹן.

Judg 16:3 … At midnight he got up, grasped the doors of the town gate together with the two gateposts, and pulled them out along with the bar. He placed them on his shoulders and carried them off to the top of the hill that is near Hebron.

In addition to his great strength, the text here implies, though it does not state definitively, that Samson is a giant: his arms spanned at least as wide as a large city gate, allowing him to tear the entire structure off its gateposts and carry it on his shoulders. Interpreting the verse, a baraita in the Babylonian Talmud makes this point explicitly (b. Sotah 10a):

תניא, א”ר שמעון החסיד: בין כתיפיו של שמשון ששים אמה היה, שנאמר… וגמירי, דאין דלתות עזה פחותות מששים אמה.

It was taught: R. Simon the Pious said: “The span of Samson’s shoulders was sixty cubits, as it says [quotes Judges 16:3]… and we have a tradition that Gaza’s city gates were never less than sixty [about 100 feet] cubits wide.”

This giant size is implied again in Samson’s final act of suicide. After he is captured and blinded, the Philistines take him out of his prison in Gaza into the Dagon Temple there, in order to poke fun at him during a celebration. Samson asks a lad to lead him to the two pillars that support the structure, which would generally be too far apart for a regular sized person to touch both. This gives Samson an idea:

שופטים טז:כט וַיִּלְפֹּת שִׁמְשׁוֹן אֶת שְׁנֵי עַמּוּדֵי הַתָּוֶךְ אֲשֶׁר הַבַּיִת נָכוֹן עֲלֵיהֶם וַיִּסָּמֵךְ עֲלֵיהֶם אֶחָד בִּימִינוֹ וְאֶחָד בִּשְׂמֹאלוֹ. טז:ל וַיֹּאמֶר שִׁמְשׁוֹן תָּמוֹת נַפְשִׁי עִם פְּלִשְׁתִּים וַיֵּט בְּכֹחַ וַיִּפֹּל הַבַּיִת עַל הַסְּרָנִים וְעַל כָּל הָעָם אֲשֶׁר בּוֹ

Judg 16:29 He embraced the two middle pillars that the temple rested upon, one with his right arm and one with his left, and leaned against them; 16:30 Samson cried, “Let me die with the Philistines!” and he pulled with all his might. The temple came crashing down on the lords and on all the people in it….

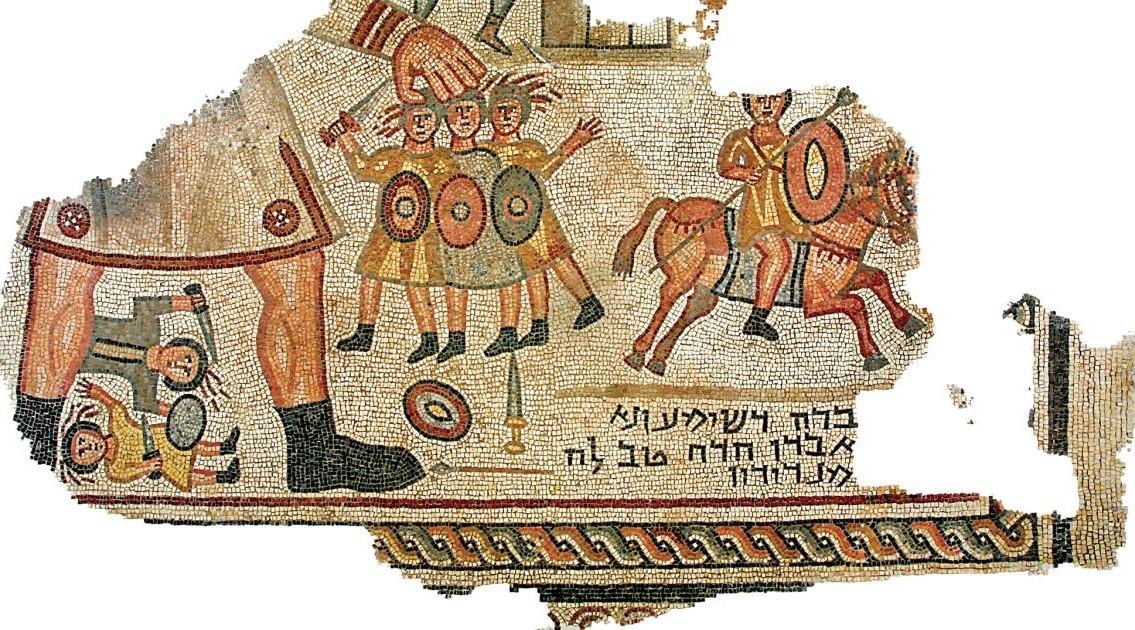

According to this, Samson’s arm-span was great enough to allow him to lean on, possibly even “grasp” (וילפת can be interpreted both ways) the two supportive pillars of an enormous temple simultaneously. In fact, at least one fifth-century Galilean mosaic in Huqoq unmistakably depicts him as a giant.[1]

A Minor Solar Deity

Samson’s name, Shimshon, recalls the common noun used for “sun,” (šemeš), as well as the proper noun that serves as the name of a solar deity in several Semitic languages, such as the Akkadian sun god Šamaš. As the ending sound “ōn” is a diminutive, his name means something like “little sun” or, if he is meant to be a demigod, “son of the sun.”[2]

A faint but unmistakable echo of this name-link is found in the Babylonian Talmud (b. Sot. 10a):

וא”ר יוחנן: שמשון על שמו של הקדוש ברוך הוא נקרא, שנאמר: כי שמש ומגן ה’ אלהים וגו’.

R. Yohanan said: “Samson was named with a name of the Holy One, blessed be he, as it says (Ps 84:12), ‘For the Lord God is sun and shield.’”

This evidence has suggested to many scholars that underlying the biblical Samson story is a myth about a solar deity impregnating a mortal woman and giving birth to a demigod.[3]In fact, hints of Samson’s semi-divine origin can be seen in the opening story about his conception (Judg 13), which insinuates the possibility of impregnation by a divine male figure.

A Visit from a Divine Being

The annunciation narrative begins by telling us that Manoah’s wife was barren and without child (Judg 13:2), and then moves on to the angel’s visit:

שופטים יג:ג וַיֵּרָא מַלְאַךְ יְ־הוָה אֶל הָאִשָּׁה וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלֶיהָ הִנֵּה נָא אַתְּ עֲקָרָה וְלֹא יָלַדְתְּ וְהָרִית וְיָלַדְתְּ בֵּן.

Judg 13:3 An angel of YHWH appeared to the woman and said to her, You are barren, and have not given birth, but you shall become pregnant and bear a son.

Here we first encounter the enigmatic angel’s suggestive grammatical prowess: the weqatal form, וְהָרִית, refers to a future conception, either imminent or distant. In verse 4, the angel instructs the woman to refrain from consuming certain substances that would conflict with the in utero naziritehood of her son:

שופטים יג:ד וְעַתָּה הִשָּׁמְרִי נָא וְאַל תִּשְׁתִּי יַיִן וְשֵׁכָר וְאַל תֹּאכְלִי כָּל טָמֵא.

Judg 13:4 Now, guard yourself, and do not drink wine or alcoholic beverages, and do not eat anything impure.

This phrasing implies that her pregnancy is immanent and, in the very next verse, the angel refers once again to her pregnancy, this time employing not the so-called “converted perfect” tense as in verse 3, but a participle, הִנָּךְ הָרָה, which often refers to the present,[4] as well as the word הנה .

שופטים יג:ה כִּי הִנָּךְ הָרָה וְיֹלַדְתְּ בֵּן…

Judg 13:5 For you are (going to be) pregnant and will bear a son…

Admittedly, such participles used in this way can denote imminent or near future events (e.g., Exod 10:4), but it is notable that the description of her status shifted in just two verses, from והרית (“you will become pregnant” v. 3) to הנך הרה (“you are pregnant” v. 5). Thus, a number of scholars have argued that the text means to imply that she got pregnant in the interim, leaving little room for the imagination as to what we are to envision having happened.[5]

One rabbinic tradition, acutely sensitive to the shift in the angel’s grammar but certainly not prepared to suggest that the angel was Samson’s biological father, offers an ingenious solution, simultaneously retaining the elements of divine impregnation and Manoah’s biological fatherhood (Numbers Rabbah, Nasso, 10:5):

“כי הנך הרה וילדת בן”: מכאן שהיתה השכבת זרע של הלילה שמורה ברחמה ולא פלטתה, וכיון שאמר לה המלאך (פס’ ג’) “והרית וילדת בן”, אותה שעה קבלה הרחם אותה טפה לשם.

“For you are pregnant and will give birth to a son”—from here we learn that the semen from the previous night remained in her womb and had not yet been expelled. Once the angel said to her “you will become pregnant and give birth to a son,” at that moment her womb accepted the drop of semen into it.

Clearly, the suggestion here is not what the text implies, but it encapsulates the question that the ambiguity posed by the grammar: whose son is Samson?

Pel’i the Playful Angel

It is easy to imagine that Manoah would be at least as troubled as some modern readers of the Samson narrative about his son’s paternity. Like the readers, he does not know for sure what happened in the field when his wife met the “man of God” other than what she tells him:

שופטים יג:ו אִישׁ הָאֱלֹהִים בָּא אֵלַי וּמַרְאֵהוּ כְּמַרְאֵה מַלְאַךְ הָאֱלֹהִים נוֹרָא מְאֹד וְלֹא שְׁאִלְתִּיהוּ אֵי מִזֶּה הוּא וְאֶת שְׁמוֹ לֹא הִגִּיד לִי. יג:זוַיֹּאמֶר לִי הִנָּךְ הָרָה וְיֹלַדְתְּ בֵּן וְעַתָּה אַל תִּשְׁתִּי יַיִן וְשֵׁכָר וְאַל תֹּאכְלִי כָּל טֻמְאָה כִּי נְזִיר אֱלֹהִים יִהְיֶה הַנַּעַר מִן הַבֶּטֶן עַד יוֹם מוֹתוֹ.

Judg 13:6 “A man of God came to me; he looked like an angel of God, very frightening. I did not ask him where he was from, nor did he tell me his name. 13:7 He said to me, ‘You are going to conceive and bear a son. Drink no wine or other intoxicant, and eat nothing unclean, for the boy is to be a nazirite to God from the womb to the day of his death!’”[6]

As noted by Zakovitch and others, the phrase “came to me” בא אלי, can also be translated as “came unto me,” a common euphemism for intercourse.[7]

To Manoah’s great chagrin, only his wife was visited by the holy man—it takes Manoah a long time to figure out he is a divine being despite his wife’s description of him. Manoah has no part in the preparatory acts for the miraculous birth, as the angel’s instructions are only for his wife.[8]

Consequently, Manoah prays to God,

שופטים יג:ח …בִּי אֲדוֹנָי אִישׁ הָאֱלֹהִים אֲשֶׁר שָׁלַחְתָּ יָבוֹא נָא עוֹדאֵלֵינוּ וְיוֹרֵנוּ מַהנַּעֲשֶׂה לַנַּעַר הַיּוּלָּד.

Judg 13:8 …“Oh, my Lord! Please let the man of God that You sent come to us again, and let him instruct us how we are to act with the child that is to be born.”

Note the triple use of the plural, emphasizing how Manoah is trying to include himself in the message. The angel indeed comes a second time, but once again only to his wife, who runs to fetch her husband. Manoah, as if unable to bring himself to repeat in the presence of the man/angel what he had said when he prayed to God in private, simply says,

שופטים יג:יב … עַתָּה יָבֹא דְבָרֶיךָ מַה יִּהְיֶה מִשְׁפַּט הַנַּעַר וּמַעֲשֵׂהוּ.

Judg 13:12 …May your words soon come true! What rules shall be observed for the boy?

The angel’s response is a seemingly straightforward reiteration of what he had said to the woman previously, and the angel even says as much (vv. 13–14). A broad consensus of ancient and modern scholars understands the angel as basically ignoring Manoah’s request to be included in the instructions.[9]And yet, this is not the whole story, since the angel uses different verbal patterns in his instructions this time around.

Identical Verb Forms with Different Meanings

In Biblical Hebrew, the forms of the second person masculine singular (2ms) and third person feminine singular (3fs) of the yiqtol (performative) verb coalesce: morphologically, they are indistinguishable. This allows for ample opportunity for ambiguity and wordplay based on person:

Judg 13:13–14

מִכֹּל אֲשֶׁר אָמַרְתִּי אֶל הָאִשָּׁה תִּשָּׁמֵר. מִכֹּל אֲשֶׁר יֵצֵא מִגֶּפֶן הַיַּיִן לֹא תֹאכַל וְיַיִן וְשֵׁכָר אַל תֵּשְׁתְּ וְכָל טֻמְאָה אַל תֹּאכַל. כֹּל אֲשֶׁר צִוִּיתִיהָ תִּשְׁמֹר.

3rd fem. sg.

From all the things against which I warned her she must abstain. She must not eat anything that comes from the grapevine, she must not drink wine or other intoxicant, and she must not eat anything unclean. She must observe all that I commanded her.

2nd masc. sg.

From all the things against which I warned her you must abstain. You must not eat anything that comes from the grapevine, you must not drink wine or other intoxicant, and you must not eat anything unclean. You must observe all that I commanded her.

Each and every one of the five primary verbs[10] in the angel’s injunctions to Manoah during the angel’s second visit can be read in two different ways. Morphologically, each of these could be interpreted as a 2ms, thus referring to Manoah, who is now being enjoined to keep strict food taboos in preparation for his son’s birth (which we imagine might please Manoah, indicating that he has an important role in the birth of their child) or as 3fs, referring to Manoah’s wife alone keeping the food-taboos (which might be less welcome news to Manoah, indicating that he has no not part in this miraculous birth).

We can imagine the poor husband eagerly following the words of the angel, sentence after sentence, verb after verb, anxiously expecting a disambiguating verb, which never comes. Not a single verb has helped Manoah understand his own position. Of course, we don’t know what Manoah’s emotional response to the angel’s instructions was, and it is possible to imagine that Manoah chose to understand the list of ambiguous verbs in his favor. Regardless, the “nail-biting” reading should affect readers, even if not Manoah himself.

Thus, the angel, who is characteristically enigmatic, leaves the characters guessing, just as the omniscient narrator leaves us readers guessing—we never find out for sure whether Manoah was to observe the food-avoidances, i.e., whether he can know for certain that he has a part in the biological constitution of this supernatural son.

Purposeful Ambiguity

The lack of disambiguation is a key feature of the story of Samson. Just as we do not know whether the angel impregnated the woman,[11] so too do we not know what Manoah’s role is to be. Why does the narrative remain ambiguous?

It could be that the author felt uneasy stating explicitly that Samson is a demigod. Alternatively, he could be asserting a hierarchy of knowledge—namely, presenting the unnamed mother as privy to precious knowledge that is known only to her and to the divine being, but not to any of the other characters or to the readers.[12] The only one who really knows for certain who Samson’s father was—aside from the divine being—is his mother[13]

The use of ambiguous language is particularly apt for a riddle-like story (and a character particularly drawn to riddles, see Judges 14:14). The playfulness of the biblical text suggests that the ambiguity is central. This tendency toward grammatical enigma in the story may serve as a hermeneutic guide, urging us to read with an eye toward the subversive and hidden meanings within the text.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

June 14, 2019

|

Last Updated

February 8, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Naphtali Meshel is a senior lecturer in the Departments of Comparative Religion and Bible at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, from where he received his Ph.D. He did post-doctoral studies in India, studying Sanskrit literature on ritual, and is the author of The “Grammar” of Sacrifice: A Generativist Study of the Israelite Sacrificial System (Oxford).

Essays on Related Topics: