Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Slaughter Remained Sacred Despite Deuteronomy, Thus Shechitah

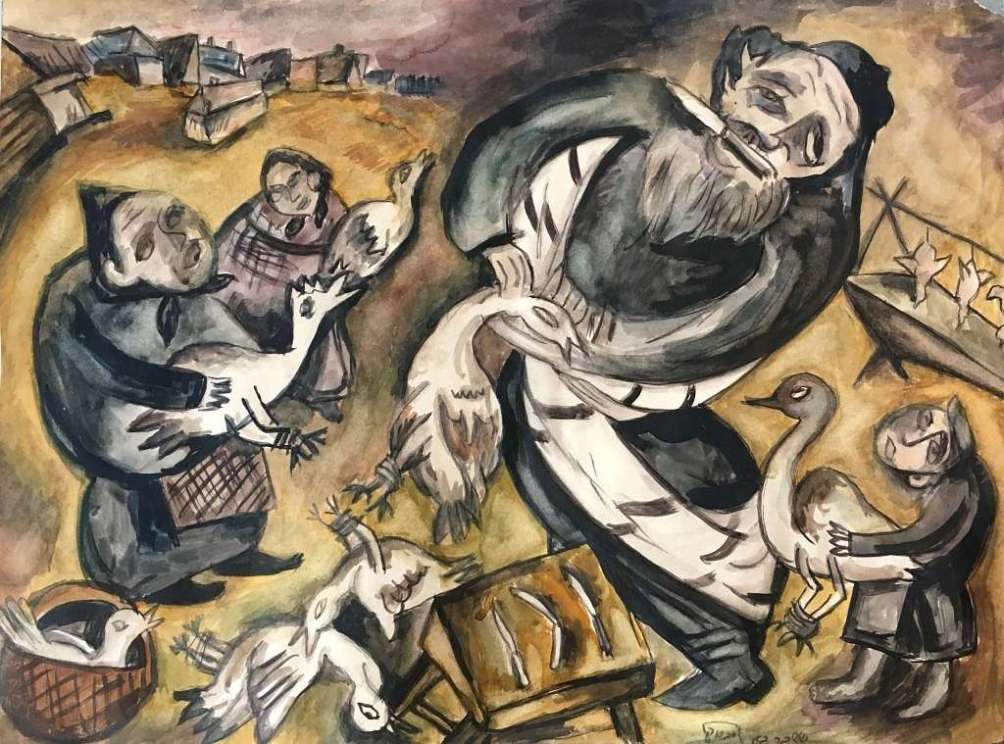

The Butcher, Issachar Ber Ryback 1917. Wikimedia

The permission to consume meat in the Torah adjusts over time:[1]

Adam is allowed to eat only fruit (Gen 2:16).

After the Flood, God allows humans to eat all animals, as long as they avoid “eating” their blood (Gen 9:3-4).

In Leviticus, this permission has narrowed; only certain animals are permitted to be consumed (ch. 11) and all domesticated animals require a sacrifice to render them fit for consumption (ch. 17).

Deuteronomy then expands this permissibility, allowing for the consumption of meat from domesticated animals without requiring ritual sacrifice (ch. 12).

Deuteronomy’s idea that domestic animals can be slaughtered for consumption “profanely” – that is, outside of any sacrificial context – is an outlier. It also would have surprised, or maybe even shocked, most people in the ancient Near East and Mediterranean. In fact, even the rabbis later found a way to tamper the radical claim of Deuteronomy 12.

Eating on the Blood and Saul’s Altar

A clear illustration of how ancient Israelites approached the slaughter and consumption of domestic animals appears in the story of Saul’s battle against the Philistines. Saul makes an oath forbidding his troops from eating until evening and only once the battle is won (1 Samuel 14:24). After the battle, the people are famished and dive quickly into eating:

שמואל א יד:לא וַיַּכּוּ בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא בַּפְּלִשְׁתִּים מִמִּכְמָשׂ אַיָּלֹנָה וַיָּעַף הָעָם מְאֹד. יד:לב (ויעש) [וַיַּעַט] הָעָם אֶל שלל [הַשָּׁלָל] וַיִּקְחוּ צֹאן וּבָקָר וּבְנֵי בָקָר וַיִּשְׁחֲטוּ אָרְצָה וַיֹּאכַל הָעָם עַל הַדָּם.

1 Sam 14:31 After they had struck down the Philistines that day from Michmash to Aijalon, the troops were very faint, 14:32 so the troops flew upon the spoil and took sheep and oxen and calves and slaughtered them on the ground, and the troops ate them with the blood.[2]

The verse does not explain what the problem is exactly, or the connection between slaughtering on the ground and “eating with the blood.” Nevertheless, the story continues with Saul being apprised of the people’s sinful behavior:

שמואל א יד:לג וַיַּגִּידוּ לְשָׁאוּל לֵאמֹר הִנֵּה הָעָם חֹטִאים לַי־הוָה לֶאֱכֹל עַל הַדָּם...

1 Sam 14:33 Then it was reported to Saul, “Look, the troops are sinning against the Lord by eating with the blood.”… [3]

Saul then decides to rectify the situation himself:

שמואל א יד:לג ...וַיֹּאמֶר בְּגַדְתֶּם גֹּלּוּ אֵלַי הַיּוֹם אֶבֶן גְּדוֹלָה. יד:לד וַיֹּאמֶר שָׁאוּל פֻּצוּ בָעָם וַאֲמַרְתֶּם לָהֶם הַגִּישׁוּ אֵלַי אִישׁ שׁוֹרוֹ וְאִישׁ שְׂיֵהוּ וּשְׁחַטְתֶּם בָּזֶה וַאֲכַלְתֶּם וְלֹא תֶחֶטְאוּ לַיהוָה לֶאֱכֹל אֶל הַדָּם...

1 Sam 14:33 …And he said, “You have dealt treacherously; roll a large stone before me here.” 14:34 Saul said, “Disperse yourselves among the troops and say to them: Let all bring their oxen or their sheep, and slaughter them here and eat, and do not sin against YHWH by eating with the blood.”[4]

Apparently, slaughtering on the large stone rectifies the problem, and this is what the people do:

שמואל א יד:לד...וַיַּגִּשׁוּ כָל הָעָם אִישׁ שׁוֹרוֹ בְיָדוֹ הַלַּיְלָה וַיִּשְׁחֲטוּ שָׁם.

1 Sam 14:34 …So all of the troops brought their oxen with them that night and slaughtered them there.

The episode ends by explaining that Saul built an altar:

שמואל א יד:לד וַיִּבֶן שָׁאוּל מִזְבֵּחַ לַי־הוָה אֹתוֹ הֵחֵל לִבְנוֹת מִזְבֵּחַ לַי־הוָה.

1 Sam 14:35 And Saul built an altar to YHWH; it was the first altar that he built to YHWH.

It is unclear if this large stone is the altar that Saul built, or whether Saul built an altar after the slaughtering on the stone in order to cook the meat and present the blood to God. In any case, the soldiers’ transgression appears to be that they ate in haste, in the exact place where they slaughtered, with the animal’s carcass sitting in the blood. Instead, before eating any livestock, they were supposed to slaughter it on a makeshift altar, whether to avoid contaminating the carcass with the blood or to offer the animal to God. Thus, the story implicitly denies the permissibility of eating livestock without some sort of ritual marker.

Meat, Altars, and Sacrifices in Ancient Israel

Putting aside the “profane-meat” law in Deuteronomy, the underlying assumption in the various legal collections in the Torah seems to be that any cattle, sheep, goat, or ox must be offered to God to render it fit for consumption. Commenting on this point, the British biblical scholar Samuel R. Driver (1846–1914) writes:

By ancient custom in Israel, slaughter and sacrifice were identical…: the flesh of domestic animals, such as the ox, the sheep, and the goat (as is still the case among the Arabs) was not eaten habitually; when it was eaten, the slaughter of the animal was a sacrificial act, and its flesh could not be lawfully partaken of, unless the fat and blood were first presented at the altar.[5]

For example, Exodus discusses the building of altars out of simple material, with the implicit assumption that they will be found all over the land:

שמות כ:כ{כד} מִזְבַּח אֲדָמָה תַּעֲשֶׂה לִּי וְזָבַחְתָּ עָלָיו אֶת עֹלֹתֶיךָ וְאֶת שְׁלָמֶיךָ אֶת צֹאנְךָ וְאֶת בְּקָרֶךָ בְּכָל הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר אַזְכִּיר אֶת שְׁמִי אָבוֹא אֵלֶיךָ וּבֵרַכְתִּיךָ. כ:כא{כה} וְאִם מִזְבַּח אֲבָנִים תַּעֲשֶׂה לִּי לֹא תִבְנֶה אֶתְהֶן גָּזִית כִּי חַרְבְּךָ הֵנַפְתָּ עָלֶיהָ וַתְּחַלְלֶהָ.

Exod 20:20{24} You need make for me only an altar of earth and sacrifice on it your burnt offerings and your offerings of well-being, your sheep and your oxen; in every place where I cause my name to be remembered I will come to you and bless you. 21{25} But if you make for me an altar of stone, do not build it of hewn stones, for if you use a chisel upon it, you profane it.[6]

As in the story of Saul after the Philistine battle, altars apparently could be created ad hoc by anyone out of dirt or stone.

The Deuteronomic Revolution

Deuteronomy, in contrast, lays out a programmatic plan for centralizing worship in “the site that the Lord your God will choose,” usually taken as a reference to Jerusalem.[7] Yet, if all domesticated animals need to be sacrificed in order to permit their consumption, limiting sacrifices to one central location would have an inevitable effect on the Israelites’ ability to consume meat. Deuteronomy’s laws address this by introducing non-sacrificial meat:

דברים יב:טו רַק בְּכָל אַוַּת נַפְשְׁךָ תִּזְבַּח וְאָכַלְתָּ בָשָׂר כְּבִרְכַּת יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ אֲשֶׁר נָתַן לְךָ בְּכָל שְׁעָרֶיךָ הַטָּמֵא וְהַטָּהוֹר יֹאכְלֶנּוּ כַּצְּבִי וְכָאַיָּל. יב:טז רַק הַדָּם לֹא תֹאכֵלוּ עַל הָאָרֶץ תִּשְׁפְּכֶנּוּ כַּמָּיִם.

Deut 12:15 Yet whenever you desire you may slaughter and eat meat within any of your towns, according to the blessing that YHWH your God has given you; the unclean and the clean may eat of it, as they would of gazelle or deer. 12:16 The blood, however, you must not eat; you shall pour it out on the ground like water.

Deuteronomy gives broad permission to eat meat without first offering the blood to YHWH on an altar. Pouring out the blood on the ground, so that it is not consumed along with the meat, is now sufficient. The passage, which underwent multiple redactions,[8] continues by repeating and highlighting the permissibility of non-sacrificial meat:

דברים יב:כ כִּי יַרְחִיב יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ אֶת גְּבוּלְךָ כַּאֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר לָךְ וְאָמַרְתָּ אֹכְלָה בָשָׂר כִּי תְאַוֶּה נַפְשְׁךָ לֶאֱכֹל בָּשָׂר בְּכָל אַוַּת נַפְשְׁךָ תֹּאכַל בָּשָׂר. יב:כא כִּי יִרְחַק מִמְּךָ הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר יִבְחַר יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ לָשׂוּם שְׁמוֹ שָׁם וְזָבַחְתָּ מִבְּקָרְךָ וּמִצֹּאנְךָ אֲשֶׁר נָתַן יְ־הוָה לְךָ כַּאֲשֶׁר צִוִּיתִךָ וְאָכַלְתָּ בִּשְׁעָרֶיךָ בְּכֹל אַוַּת נַפְשֶׁךָ.

Deut 12:20 When YHWH your God enlarges your territory, as he has promised you, and you say, “I am going to eat some meat,” because you wish to eat meat, you may eat meat whenever you have the desire. 12:21 If the place where YHWH your God will choose to put his name is too far from you, and you slaughter as I have commanded you any of your herd or flock that YHWH has given you, then you may eat within your towns whenever you desire.

Even an impure person can now eat meat from domesticated animals, like they always could with wild animals, given that these animals aren’t sacrificed. The one thing demanded is that the blood of domesticated animals, which is their nefesh—“life, soul, or spirit”—be separated from the meat consumed:

דברים יב:כב אַךְ כַּאֲשֶׁר יֵאָכֵל אֶת הַצְּבִי וְאֶת הָאַיָּל כֵּן תֹּאכְלֶנּוּ הַטָּמֵא וְהַטָּהוֹר יַחְדָּו יֹאכְלֶנּוּ. יב:כג רַק חֲזַק לְבִלְתִּי אֲכֹל הַדָּם כִּי הַדָּם הוּא הַנָּפֶשׁ וְלֹא תֹאכַל הַנֶּפֶשׁ עִם הַבָּשָׂר. יב:כד לֹא תֹּאכְלֶנּוּ עַל הָאָרֶץ תִּשְׁפְּכֶנּוּ כַּמָּיִם.

Deut 12:22 Indeed, just as gazelle or deer is eaten, so you may eat it; the unclean and the clean alike may eat it. 12:23 Only be sure that you do not eat the blood, for the blood is the life, and you shall not eat the life with the meat. 12:24 Do not eat it; you shall pour it out on the ground like water.

The passage claims that profane consumption of meat is now legitimate, thus solving the problem caused by the centralization of worship. But if we take a step back Deuteronomy’s technical secularization of slaughtered meat wouldn’t have changed the Israelite stance towards their religious experience of slaughtering and consuming domesticated animals.

An Intellectual Reframing

Some scholars date the earliest form of Deuteronomy to the reign of King Hezekiah of Judah (r. ca. 715–686 B.C.E.). This is when the book of Kings reports a first attempt by a king to centralize worship by cancelling worship sites outside the Jerusalem Temple, though whether Hezekiah really attempted such a thing is a matter of debate.[9] As with much of Deuteronomy, we are likely dealing here with an idealistic program composed by palace scribes. Such a text would not govern public policy and the vast majority of Hezekiah’s subjects (and even Hezekiah himself) probably did not even know it existed.[10]

An early form of Deuteronomy likely emerged in the time of King Josiah, in the form of the scroll found by the High Priest Hilkiah in the Temple (2 Kgs 22–23). And Josiah is said to have applied elements from this scroll, razing local temples and trying to consolidate all sacrificial activity in the Jerusalem Temple.[11] Yet still, outside the world of the elites, it is likely that nothing much changed.

Taking Saul’s altar as a paradigm, whenever Israelites consumed meat, at wedding feasts or other festive occasions, they likely slaughtered the animal on some kind of structure to ensure that the blood poured onto the ground and did not seep back into the carcass. The average Israelite would not have accepted Deuteronomy’s description of the slaughter of a flock animal as profane, free from sacral value. The slaughter of a domestic animal was always a sacred act. YHWH, having both provided the animal and allowed for the taking of its life, must be acknowledged.

Even the writers of this passage appear not to have been entirely convinced of their answer since they use the verb zevaḥ, which normally refers to sacrifice. The authors wavered between the conventional view of seeing such a slaughter as a quasi-sacrifice and their more intellectually satisfying but radical solution as seeing it as completely severed from the sancta.

The Priestly View

Unlike Deuteronomy, the Holiness laws require all slaughtering of domesticated animals to take place on an altar as a sacrificial offering:

ויקרא טז:ג אִישׁ אִישׁ מִבֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל אֲשֶׁר יִשְׁחַט שׁוֹר אוֹ כֶשֶׂב אוֹ עֵז בַּמַּחֲנֶה אוֹ אֲשֶׁר יִשְׁחַט מִחוּץ לַמַּחֲנֶה. טז:ד וְאֶל פֶּתַח אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד לֹא הֱבִיאוֹ לְהַקְרִיב קָרְבָּן לַי־הוָה לִפְנֵי מִשְׁכַּן יְ־הוָה דָּם יֵחָשֵׁב לָאִישׁ הַהוּא דָּם שָׁפָךְ וְנִכְרַת הָאִישׁ הַהוּא מִקֶּרֶב עַמּוֹ.

Lev 17:3 If anyone of the house of Israel slaughters an ox or a lamb or a goat in the camp or slaughters it outside the camp 17:4 and does not bring it to the entrance of the tent of meeting, to present it as an offering to YHWH before the tabernacle of YHWH, he shall be held guilty of bloodshed; he has shed blood, and he shall be cut off from the people.

This passage either does not know Deuteronomy 12 or to pushes back on it.[12] Scholars usually assign this chapter to the H (Holiness) source, dated to well after Deuteronomy and even after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in the sixth century B.C.E. It continues by explaining that the Israelites should not offer the animal on their own, in the field, but they should have the sacrifice performed by a priest:

ויקרא טז:ה לְמַעַן אֲשֶׁר יָבִיאוּ בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶת זִבְחֵיהֶם אֲשֶׁר הֵם זֹבְחִים עַל פְּנֵי הַשָּׂדֶה וֶהֱבִיאֻם לַי־הוָה אֶל פֶּתַח אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד אֶל הַכֹּהֵן וְזָבְחוּ זִבְחֵי שְׁלָמִים לַי־הוָה אוֹתָם. יז:ו וְזָרַק הַכֹּהֵן אֶת הַדָּם עַל מִזְבַּח יְהוָה פֶּתַח אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד וְהִקְטִיר הַחֵלֶב לְרֵיחַ נִיחֹחַ לַי־הוָה. יז:ז וְלֹא יִזְבְּחוּ עוֹד אֶת זִבְחֵיהֶם לַשְּׂעִירִם אֲשֶׁר הֵם זֹנִים אַחֲרֵיהֶם חֻקַּת עוֹלָם תִּהְיֶה זֹּאת לָהֶם לְדֹרֹתָם.

Lev 17:5 This is in order that the Israelites may bring their sacrifices that they offer in the open field, that they may bring them to YHWH, to the priest at the entrance of the tent of meeting, and offer them as sacrifices of well-being to YHWH. 17:6 The priest shall dash the blood against the altar of YHWH at the entrance of the tent of meeting and turn the fat into smoke as a pleasing odor to YHWH. 17:7 so that they may no longer offer their sacrifices for goat-demons, to whom they prostitute themselves. This shall be a statute forever to them throughout their generations.

There is no such thing as “profane” slaughter here. If slaughtered properly, at the Tabernacle, it is a sacrifice to YHWH. If slaughtered improperly, in the open field, it is a sacrifice to the goat-demons.

Given that the law is phrased as if the people are in the wilderness—though the phrase עַל פְּנֵי הַשָּׂדֶה “in the field” reveals its hand—and there is one camp with a central Tabernacle, it remains unclear how this text was meant to be applied in actual life. In the First Temple period, the assumption is that they will go to local shrines. But how might this apply when the Temple is destroyed, when there are no local shrines, and the priests and intellectual elite are still in exile in Babylonia? Nevertheless, it unequivocally denies the possibility of profane slaughter that Deuteronomy envisions.

The Blood of Domestic Animals

The passage goes on to explain that the reason profane slaughter is such a violation is for the same reason blood consumption is prohibited: because the blood is the nefesh, “life, soul, or spirit”—the same argument Deuteronomy gives for requiring the blood to be spilt on the ground:

ויקרא יז:יא כִּי נֶפֶשׁ הַבָּשָׂר בַּדָּם הִוא וַאֲנִי נְתַתִּיו לָכֶם עַל הַמִּזְבֵּחַ לְכַפֵּר עַל נַפְשֹׁתֵיכֶם כִּי הַדָּם הוּא בַּנֶּפֶשׁ יְכַפֵּר.

Lev 17:11 For the life of the flesh is in the blood, and I have given it to you for making atonement for your lives on the altar, for, as life, it is the blood that makes atonement.

In the Holiness perspective, this means a priest must collect the blood of any domestic animal slaughtered for consumption and it must be dashed on the altar. In contrast, wild animals, which are not offered as sacrifices, need only have their blood poured out and covered with earth.[13] Leviticus rejects Deuteronomy’s claim that slaughter of domesticated animals is the same as that of wild animals; the power of the blood of these kinds of animals is different.

Ritual Shechitah Takes the Place of Sacrifice

In their discussion of profane meat (ḥullin), the rabbis seek to link rather than uncouple the slaughter of domestic animals to the sacred. Rabbinic law takes great care to make the slaughter of domestic animals into a quasi-sacrifice, requiring similar (although not identical) ritual treatment as the sacrifices. In doing so, they sought to bring common practice and understanding in line with Scripture.[14]

They note that Deuteronomy 12:15 and 21 use the verb zevaḥ. Since this verb is also generally used in sacrificial contexts, they make an analogy:

ספרי דברים עה "כאשר צויתיך" (דברים יב:כא)—מה קדשים בשחיטה אף חולין בשחיטה.

Sifre Deuteronomy 75:6 “As I have commanded you” (Deut 12:21)—Just as sacrificial animals must be ritually slaughtered so too non-sacrificial animals must be ritually slaughtered.

As the Torah does not contain any specific rules about how animals are to be slaughtered, the rabbis understand the phrase “as I have commanded you” as an allusion to an oral teaching that details the specific laws of slaughter, such as the need to draw a sharp blade along the throat of the animal. Whereas Deuteronomy 12 seeks to create a space for non-sacrificial slaughter by equating domesticated animals with wild ones, the rabbis move in the opposite direction, equating all animals – domesticated or wild – with those domesticated animals intended for sacrifice.[15]

Rabbinic law here probably draws more on common Jewish practice than it does on Deuteronomy. Jews in the rabbinic period (Late Antiquity) lived in what we might term a sacrificial culture, as did their biblical ancestors. Greek and Roman neighbors commonly slaughtered their domestic animals with sacrificial gestures (e.g., salting the animal), even when outside of a temple.[16]

Jews may not have had access to actual sacrifices after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 C.E., but they may have desired cognitive workarounds to bring their slaughtering practices in line with their understanding – derived from the world around them and perhaps reinforced by their understanding of Leviticus 17 – that the preparation of meat is intrinsically linked to sacrifice.

The Mishnah seems to acknowledge this implicitly:

משנה חולין ב:י הַשּׁוֹחֵט לְשֵׁם עוֹלָה, לְשֵׁם זְבָחִים, לְשֵׁם אָשָׁם תָּלוּי, לְשֵׁם פֶּסַח, לְשֵׁם תּוֹדָה, שְׁחִיטָתוֹ פְסוּלָה. וְרַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן מַכְשִׁיר....

m. Hullin 2:10 One who slaughters for the sake of a burnt offering, for sacrifices, for a provisional guilt offering, for the Paschal sacrifice, or for a thanksgiving offering, his slaughter is invalid. And Rabbi Shimon says it is valid….

הַשּׁוֹחֵט לְשֵׁם חַטָּאת, לְשֵׁם אָשָׁם וַדַּאי, לְשֵׁם בְּכוֹר, לְשֵׁם מַעֲשֵׂר, לְשֵׁם תְּמוּרָה, שְׁחִיטָתוֹ כְשֵׁרָה. זֶה הַכְּלָל, כָּל דָּבָר שֶׁנִּדָּר וְנִּדָּב, הַשּׁוֹחֵט לִשְׁמוֹ, אָסוּר, וְשֶׁאֵינוֹ נִדָּר וְנִדָּב, הַשּׁוֹחֵט לִשְׁמוֹ, כָּשֵׁר.

One who slaughters for the sake of a sin offering, for a certain guilt offering, for an offering of the firstborn, for a tithe, or for a substitution [for a sacrifice], his slaughter is valid. This is the principle: Any offering made for the sake of fulfilling a vow or consecrated gift, the [animal] is forbidden. But any animal that is not for the fulfillment of a vow or is a consecrated gift, the slaughtered [animal] is kosher.

The Mishnah provides indirect evidence that Jews could well have been thinking of their profane slaughter as sacrificial, exactly what one would expect. Such thoughts, the Mishnah assures us, although not ideal, ordinarily do not invalidate the animal for consumption.

The Push and Pull of Profane Meat

In sum, ancient Israelites, like nearly all of their neighbors, saw the killing of (particularly) animals for consumption as “sacrificial,” with the blood going to the deity. It was never a simply neutral act. In response to the centralization of worship ideal, Deuteronomy developed an understanding of “profane” meat, by which the slaughter of animals is separated from the holy, but this was rejected or ignored in Leviticus in favor of the rule that all domestic animals killed for consumption must be offered by a priest upon an altar.

The Rabbis, living in a world like their ancient Israelite progenitors, in which nearly all slaughter of domestic animals was seen as “sacrificial,” provide a halakhic framework, whereby the slaughter of all animals, domestic and wild, for consumption becomes quasi-sacrificial.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

August 22, 2025

|

Last Updated

December 22, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Michael L. Satlow is Professor of Judaic Studies and Religious Studies at Brown University. He holds a Ph.D. from JTS, is the author of Creating Judaism: History, Tradition, Practice and How the Bible Became Holy and the editor of Judaism and the Economy: A Sourcebook. He maintains a blog at mlsatlow.com.

Essays on Related Topics: