Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Spilling Wine While Reciting the Plagues to Diminish Our Joy?

The Ten Plagues from the Braginsky Leipnik Haggadah with Abarbanel's commentary, 1739. e-codices.unifr.ch

During the Passover seder, when we retell the story of the exodus, we list the ten plagues.[1] A popular custom is to remove a drop of wine for each plague we recite.[2] Virtually every modern Haggadah explains this custom in the same way. To quote the Artscroll Youth Haggadah: “We don't want our cups to be full when we tell about other people's pain.”[3] Similarly, the A Different Night Haggadah explains: “As each plague is recited, we decrease our own joy, drop by drop, as we recall the enemies pain.”[4]

What is the origin of this explanation?

Don Isaac Abarbanel?

A number of haggadot site medieval authorities for this explanation. For instance, A Different Night quotes it in the name of Don Isaac Abarbanel (1437–1508), as the third of five examples of sources dealing with the importance of restraint when it comes to revenge:

By spilling a drop of wine from the Pesach cup for each plague, we acknowledge that our own joy is lessened and incomplete, for our redemption had to come by means of the punishment of other human beings. Even though these are just punishments for evil acts, it says, “Do not rejoice at the fall of your enemy” (Proverbs 24:17).[5]

The Artscroll Mesorah Series Haggadah makes the same attribution.[6] Nevertheless, this idea does not actually appear in the Abarbanel's commentary to the haggadah, or in any of his writings.[7]

As far as I have been able to trace it, the attribution of this idea to Abarbanel first appears in “Fun Unzer Alten Otzar,” Moshe Bunem Justman’s (1889–1942) column for the Warsaw newspaper Hajnt, in an article dated March 26, 1937 (p. 6).[8] These were later collected in the Fun Unzer Alten Otzar series of books, including a published haggadah in 1938.[9] From there it made its way to various collections of material on Passover,[10] most significantly to the “overwhelmingly popular”[11] Hebrew Yalkut Tov Haggadah by R. Eliyahu Kitov, first published in 1961 and many times since.[12]

R. David Abudraham?

Other haggadot cite an even earlier authority, R. David Abudraham of Seville(14th century), known for his book on prayer. For example, The Haggadah Treasury (Artscroll, 1978) references him as the source for this explanation,[13] as does the Rabbi Jonathan Sacks's Haggadah.[14] This idea, however, does not actually appear in the writings of Abudraham, and all modern English haggadot that offer this attribution are likely using ArtScroll as their (incorrect) source.

The Early Ashkenzi Custom

The custom of removing wine is first mentioned in a Pesach derashah (sermon) of Rabbi Eleazer of Worms (1176–1238), known as “the Rokeach” after his work of that name.[15] After noting that this is a practice he learned from his teachers, he offers symbolic interpretations based on the number 16, which is the number of times wine is taken out (3 for the portents in Joel; 10 for the plagues; 3 for the mnemonic for remembering the plagues):

י"ו פעמים מטיפין לחוץ, כנגד חרבו של הקב"ה י"ו פנים, וי"ו פעמים דבר בירמיה, לומר לנו לא יזיק, מיכן סמכו אבותינו.

Sixteen times they spill out a drop, matching the sword of the Holy One, blessed be He, which has sixteen sides. And the sixteen mentions of plague in Jeremiah. [This custom] teaches us that we will not be injured. Based upon [this] our ancestors created this custom.[16]

The text continues with four other things the number 16 symbolizes: The 16 times the word חיים “life” appears in Psalm 119; the 16 people who read the Torah each week; the 16 lambs sacrificed in a week; the gematria of the word היא “it” in the phrase עץ חיים היא “it is a tree of life” (3:18).[17]

Nothing About Lessening Joy

R. Eleazar is primarily interested in the symbolism of the number 16, and none of his explanations has any connection to the idea of lessening our enjoyment or feeling bad for Egyptians. In fact, we also remove wine for the verse from Joel describing what God will do immediately before the “day of YHWH” arrives:

יואל ג:ג וְנָתַתִּי מוֹפְתִים בַּשָּׁמַיִם וּבָאָרֶץ דָּם וָאֵשׁ וְתִימֲרוֹת עָשָׁן.

Joel 3:3 [2:30] I will set portents in the sky and on earth: Blood and fire and pillars of smoke.[18]

This text is certainly not about the plagues of Egypt,[19] and thus, the original reason for this custom cannot be about feeling bad for Egyptians.

Late 19th and early 20th century haggadot offer a simpler reason offered in popular books of explanations for customs, that the removal of drops of wine from the cup parallels the Egyptians, who were "lessened" with every plague. These too contain no trace of the idea of "incomplete joy" due to the suffering of the Egyptians, and, in fact, seem diametrically opposed to it.[20] Given that the incomplete joy explanation of the custom has no root in medieval sources, what is its actual origin?

Finding the Earliest Mention

In his introduction to his 1947 commentary to the Haggadah, Daniel Goldschmidt (1895–1972), the great scholar of Jewish liturgy, writes that

In recent times an attempt has been made to explain this custom in a more ethical manner, and give it a meaning that is appropriate for modern sensibilities, as if we are symbolically lessening the joy of the holiday due to consideration of the downfall of the Egyptians, based on the verse "If your enemy falls do not exult" (Proverbs 24:17).

In a note he attributes this explanation to two German Orthodox rabbis.[21]

R. Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808–1888)

The first reference is to the famous spiritual father of modern Orthodoxy, R. Samson Raphael Hirsch. Goldschmidt, however, gives no reference to support this,[22] and, as far as I can tell, Hirsch never wrote about this.[23]

Luckily, Goldschmidt’s second reference, to a much more obscure scholar, is more fruitful and can lead us, with a little detective work, to the likely origin of this explanation.

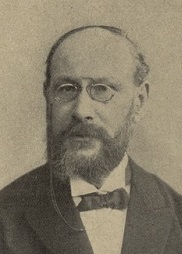

R. Eduard Ezekiel Baneth (1855–1930)

Rabbi Dr. Eduard Ezekiel Baneth studied at the Hildesheimer Rabbinical Seminary in Berlin and was ordained by its founder, Rabbi Israel Hildesheimer.[24] He served as the rabbi of Krotoszyn, Poland, and later was a professor of Talmud at the Lehranstalt fur de Wissenschaft des Judentums in Berlin, where he was succeeded by the great scholar of rabbinics, Chanoch Albeck.[25]

Baneth mentions the "incomplete joy" explanation for taking some wine out of the cup at the Seder in his Der Sederabend: Ein Vortrag, a lecture on the Pesach Seder published in Berlin in 1904:

Here the ten plagues will be enumerated, and it is a widespread—though not particularly old—custom to remove a drop of wine from the cup for each plague.

This strange practice was explained to me, when I was still a boy, that wine is a symbol of joy, and because each plague caused our tormentors to suffer on our account, the joy over our own liberation is diminished.

Baneth is aware that this is not the traditional explanation for the custom, and thus he continues:

Whether this explanation may make claim to historical truth may remain unanswered, but one must recognize the poetic truth in it, because it breathes the spirit of Judaism.[26]

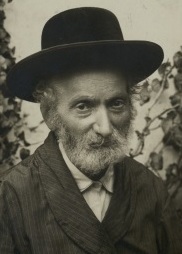

R. Eliyahu Klatzkin (1852–1932)

Rabbi Eliyahu Klatzkin, the famed “ilui from Shklov” who served as Chief Rabbi of Lublin from 1910–1928, a contemporary of Baneth, mentions this explanation in his קונטרס לדוגמא (A Notebook of Examples), a 24 page booklet of miscellaneous material from works that Rabbi Klatzkin began writing but never completed. [27]

In the section of homiletic material on Parashat Ve'era, Klatzkin writes:

והנה לא נתנהג כמעשה הגוים השמחים למפלת אויביהם כאשר יחזו נקם ויפילו מהם חללים... ובעת שנזכיר ונספר מהמכות שהביא הקב"ה על המצרים, דצ"ך עד"ש באח"ב, וכן באמרנו "דם ואש ותמרות עשן" שהוא הזכרת העונש, נשפוך ונחסיר הכוסות ע"י נטיפות טפות טפות.

We do not act like the Gentiles who are joyous at the downfall of their enemies when they see vengeance and kill them… and when we mention and tell of the plagues the Holy One, blessed by He, brought on the Egyptians, the mnemonic, and when we say “blood, fire, and pillars of smoke,” which is a reference to punishment, we pour out and diminish the cups through dripping out drop by drop.[28]

Like Baneth, Klatzkin is aware that this is not the traditional explanation, which he quotes later in the text. Nevertheless, he does not claim to have invented the explanation himself. Haggadot that focus on the rabbis of Jerusalem cite him as this explanation’s source, but this is because Klatzkin moved to Jerusalem in 1928 and brought this explanation with him.[29] Moreover, Baneth says he heard it when he was a boy, and since Klatzkin is only three years his senior, he could not have been the source. As it is hard to imagine that both came up with it independently at the same time, where did the idea originate?

The Origin: R. Yirmiyahu Löw (1812-1874)

The book Divrei Yirmiyahu – Drashot is a collection of the derashot (homilies) of R. Yirmiyahu Löw (1812-1874), compiled by his grandson, R. Binyamin Zev Lev (Löw). In the last pages of the book, some extra material is added שלא להוציא הנייר חלק “in order not to leave blank pages.”

There, the author, R. Binyamin Zev Lev, brings the “incomplete joy” explanation in the name of his grandfather:

זקני הקדוש ז"ל נתן טעם לשבח מדוע שופכין בליל פסח מכוס ישועות אצל כל מכה מעט מזעיר יען

My grandfather gave a nice explanation for why on Passover night we pour out a little bit [of wine] from the cup of salvation for each plague:

כי רחמי ישראל מרובים ועל ידי הצלתינו ממצרים נאבדו ונטבעו נבראי ה' לזאת הגם כי שמחה גדולה לנו אשר הוציא אותנ[ו][30] מיד מצרים וגאל אותנו אולם צער לנו כי עי"ז נאבדו אחרים כי גם ענוש לצדיק לא טוב ואם הי"ת הציל אותנו מבלי שיהי' אבדון ומות לאחרים הי' יותר שמחת נפש לנו

Since the Jewish people are filled with mercy, and through our being saved from Egypt, God’s creatures were lost and drowned. Although it is a great joy for us that God took us out of Egypt and redeemed us, it is still painful for us that through this others were destroyed, “for punishment to the righteous is not good” (Prov 17:26). If God had saved us without causing loss and death to others, it would have been a greater happiness for us.

ע"כ עי"ז נתמעט מעט משמחתינו לזאת להראות כי ישראל רחמנים בני רחמנים נשפוך מעט אצל כל מכה ומכה וק"ל.

Therefore, through this our joy was a little diminished, and to show that Israel are merciful and the children of merciful, we pour out a little [wine] at every plague. And this is simple to understand.[31]

In the formulation of R. Yirmiyahu Löw, there is nothing inherently unethical or inappropriate about the celebrating the destruction of enemies, however since "Israel are merciful and the children of merciful" we go beyond normal moral standards and express diminished joy because of the deaths of the Egyptians.

From Löw to Baneth to the World

The rabbinical figures in the Löw and Baneth families were connected for generations, and it is reasonable that a member of the Baneth family related an explanation heard from Löw, who was still alive when Baneth was a boy, at the family seder.[32]

While the comments of Löw and Klatzkin are published in obscure works, Baneth’s lecture on the seder was better known, and considered significant in its time.[33] Thus it is likely his adoption of the idea that led to its introduction into haggadot and the public consciousness.[34] Nevertheless, it remains unclear how the explanation offered to the young Eduard Baneth came to be associated with Abarbanel and Abudraham.

What these authorities have in common is that their names begin with the letters אב, the same letters as the Hebrew initials of Eduard Baneth. Thus it is possible that a writer saw this explanation written in Hebrew in the name of ר' אב and misunderstood these letters as referring to the first two letters of either Abrabanel or Avudraham.[35]

No Singing While Egyptians are Drowning: A Midrashic Precedent

Although the "incomplete joy" explanation seems to express modern sensibilities and possibly political correctness, R. Yirmiyahu Löw was not known for these characteristics. In fact, Löw was a “recognized leader of Hungarian Orthodoxy,” who was a vigorous opponent of Hasidism, Reform[36] and Haskalah (the Jewish enlightenment).[37]

While it is hard to deny that the idea is appealing to modern sensibilities, it also connects to traditional Jewish sources as well. Löw himself does not note this, but both Klatzkin and Baneth support the idea with a well-known rabbinic midrash. Thus, Klatzkin writes:

כי עלינו "להלך אחרי מדותיו של הקב"ה" (סוטה ד' י"ד), וכמ"ש "שאין הקב"ה שמח במפלתם של רשעים כו' [באותה שעה בקשו מלאכי השרת לומר שירה לפני הקדוש ברוך הוא,] אמר להן הקב"ה מעשה ידי טובעין בים ואתם אומרין שירה לפני" (סנהדרין ד' ל"ט).

It is up to us to “follow the character traits of the Holy One, blessed by He” (b. Sotah 14), as it is written, “The Holy One, blessed be He does not rejoice over the fall of the wicked…” [at that moment the ministering angels wished to sing before the Holy One, blessed by He.] The Holy One, blessed be He said to them: “My handiwork is drowning in the sea and you are singing before me?!” (b. San 39b).

Admittedly, the Torah records how the Israelites sang a song at that very moment, and no criticism is offered of this, but certainly Klatzkin’s connecting this story and the custom as understood by Löw has an authentic ring.

Baneth makes a similar connection, this time to one of the traditional explanations for why only half Hallel is recited on all but the first day of Passover (in contrast to Sukkot during which the full Hallel is recited every day):

Already in midrash the rule as to why “Half-Hallel” is to be recited during the latter days of Passover were justified in a similar manner: We cannot sing a full song of thanksgiving for the salvation of our people, which was purchased so dearly with the sinking of the pursuers into the Red Sea.[38]

This explanation for the rule does not appear in the Talmud, but in Pesiqta de-Rav Kahana, as well as in an obscure midrashic work called Midrash Harninu, and subsequently codified in the 13th-century halakhic works Shibbolei haLeket (§174) and Kolbo (§52), and finally by R. Joseph Karo (Beit Yosef O.H. 490:4).[39] Thus, even though it took until the 19th century for the incomplete joy explanation to enter Jewish consciousness, the groundwork for the idea goes back to rabbinic times. In fact, it goes back to the Bible as well, as it is an important theme in the book of Jonah.

A New Explanation Becomes Quasi-Canonical

Until the innovation of the “incomplete joy” idea,[40] the explanation for wine being poured out was mystical, as noted by R. Eleazar of Worms quoted above, and the emphasis was on the number 16, rather than on the act of pouring the wine itself. It is unclear why this earlier explanation lost popularity. Perhaps it is because they are difficult to use in the context of a family Seder as it is based on the esoteric imagery such as the sixteen-sided sword of God as well as the general symbolism behind the number sixteen, something obscure and difficult to connect with.

Once Löw’s incomplete joy explanation was popularized by Baneth, it quickly took off. It resonated with the sensibilities of English-speaking American Jews in particular, as it was seen as more humane and understandable than the original explanation. In fact, this explanation became the only one presented in many early English language haggadot intended for laypeople.

Early English-translation haggadot generally either do not explain the reason for the custom, or gave explanations closer to the original one. For example, J.D. Eisenstein's Hagada: Seder Ritual for Passover Eve (New York: Hebrew Publishing Company, 1928), p. 18, explains that “we spill out a drop of wine at the mention of each plague to indicate we are immune from the plagues.”

Entering English Haggadot

The shift begins in 1929, in an English translation haggadah published by the Austrian/Hungarian Schlesinger publishing house, where we see the custom explained this way: “we cannot celebrate the feast of our deliverance full of joy when so many thousands of human beings have perished.”[41]

In the 1940s, 50s and 60s this explanation became ubiquitous in American haggadot. The haggadah edited by David and Tamar De Sola Pool, first published in 1943 by the National Jewish Welfare Board for members of the armed forces of the United States, similarly explains that “a drop of wine of rejoicing is diminished from the cup in sign of pity for the suffering Egyptians.”[42] This Haggadah is particularly noteworthy since it addresses the "compatibility of Jewish and American values."[43] In particular, the American value here is "the liberal ethic, believing that all people are essentially good," so that punishing the Egyptians "seems so vindictive and vengeful."[44]

The haggadah edited by Philip Birnbaum for the Hebrew Publishing Company in 1953, considered the standard traditional haggadah for English speakers until the late 70s,[45] also states that the custom “is intended to stress the idea that we must not rejoice over the misfortunes that befell our foes.”[46] Rabbi Shlomo Kahn's 1960 Haggadah, From Twilight Till Dawn, billed “the traditional Passover Haggadah,” also explains how this custom reminds us that the Egyptians “although our enemies and tormentors, were fellow human beings nevertheless.”[47]

We can say that since World War II, every American haggadah aimed at a primarily English speaking audience which offered an explanation for this custom provided the "incomplete joy" explanation, and in most cases it was the only explanation offered.[48] It is even the explanation given on the Wikipedia entry for "Passover Seder"![49]

Scholarly Orthodox Haggadot

This approach is found more scholarly Orthodox literature as well.[50] It is particularly prevalent in works written by people connected to English speaking countries, where this explanation was most widely popularized. For example, it is included in R. David Feinstein's The Kol Dodi Haggadah[51] and in Rabbi Yaakov Wehl's The Haggadah With Answers, in both the Hebrew and English versions.[52]

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks calls it “the most beautiful” explanation for the custom, and does not offer alternative explanations.[53] Rabbi Shlomo Riskin includes it in his Haggadah, stating that “it symbolizes our sadness at the loss of human life – even that of our enemies.”[54] It appears in many mainstream scholarly Hebrew haggadot as well.[55]

A Compassionate Custom

The almost total conquest this explanation has made in Jewish circles, Ashkenazi and Sephardi, traditional and secular, speaks to the unique way it succeeds in bridging the Jewish and modern notions of compassion for the other, and thus offering ethical relevance to an old custom that originally had no ethical significance.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

April 6, 2020

|

Last Updated

January 1, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Rabbi Zvi Ron is an educator living in Neve Daniel, Israel. He holds a Ph.D. in Jewish Theology from Spertus University and semikhah (rabbinic ordination) from the Israeli chief rabbinate. He is editor of the Jewish Bible Quarterly and has published over sixty scholarly articles on the Bible, Pseudepigrapha, Midrash, and Jewish customs in Tradition, Hakirah, Zutot, Sinai, ha-Ma'ayan, the Review of Rabbinic Judaism, the Journal of Jewish Music and Liturgy, the Jewish Bible Quarterly and others. He is the author of ספר קטן וגדול about all the big and small letters in the Bible and ספר עיקר חסר about variant spellings of biblical words.

Essays on Related Topics: