Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Decalogue: Ten Commandments or Ten Statements?

The Decalogue (adapted), Beth Jacob Cemetery, Finksburg, Maryland. Wikimedia

A “Decalogue” in Exodus

The revelation of the Decalogue appears in Exodus 19-20, but it is not referred to there as עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים (aseret hadevarim), The Ten Statements (later known as “The Ten Commandments”).[1] The phrase does appear about a dozen chapters later,[2] when Moses goes up the mountain to get a second set of tablets:

שמות לד:כח וַֽיְהִי־שָׁ֣ם עִם־יְ־הוָ֗ה אַרְבָּעִ֥ים יוֹם֙ וְאַרְבָּעִ֣ים לַ֔יְלָה לֶ֚חֶם לֹ֣א אָכַ֔ל וּמַ֖יִם לֹ֣א שָׁתָ֑ה וַיִּכְתֹּ֣ב עַל־הַלֻּחֹ֗ת אֵ֚ת דִּבְרֵ֣י הַבְּרִ֔ית עֲשֶׂ֖רֶת הַדְּבָרִֽים׃

Exod 34:28 And he was there with YHWH forty days and forty nights; he ate no bread and drank no water; and he wrote down on the tablets the terms of the covenant, the ten devarim.[3]

It is possible that ten devarim in this verse refers to the list of laws in Exodus 20 (vv. 2–17) known as the Decalogue. Nevertheless, many scholars have argued that the ten devarim here refer to the laws found in chapter 34 itself (vv. 11–26), naming them “the Cultic Decalogue.”[4]

The Decalogue in Deuteronomy

In its retelling of the wilderness account, Deuteronomy 5 quotes the Decalogue in full—albeit with several stark differences—also without using the term עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים. But the term does appear earlier in the book, during Moses’s description of the theophany at Mount Horeb (Deuteronomy’s name for Mount Sinai):

דברים ד:יג וַיַּגֵּ֨ד לָכֶ֜ם אֶת־בְּרִית֗וֹ אֲשֶׁ֨ר צִוָּ֤ה אֶתְכֶם֙ לַעֲשׂ֔וֹת עֲשֶׂ֖רֶת הַדְּבָרִ֑ים וַֽיִּכְתְּבֵ֔ם עַל־שְׁנֵ֖י לֻח֥וֹת אֲבָנִֽים׃

Deut 4:13 He declared to you the covenant that He commanded you to observe, the ten devarim; and He inscribed them on two tablets of stone.

Later, when again discussing the theophany, Moses recounts being called up to the mountain to get a second set of tablets:

דברים י:ד וַיִּכְתֹּ֨ב עַֽל־הַלֻּחֹ֜ת כַּמִּכְתָּ֣ב הָרִאשׁ֗וֹן אֵ֚ת עֲשֶׂ֣רֶת הַדְּבָרִ֔ים אֲשֶׁ֣ר דִּבֶּר֩ יְ־הוָ֨ה אֲלֵיכֶ֥ם בָּהָ֛ר מִתּ֥וֹךְ הָאֵ֖שׁ בְּי֣וֹם הַקָּהָ֑ל וַיִּתְּנֵ֥ם יְ־הוָ֖ה אֵלָֽי׃

Deut 10:4 He inscribed on the tablets the same text as on the first, the ten devarim that YHWH addressed to you on the mountain out of the fire on the day of the Assembly; and YHWH gave them to me.

In both of these cases, the referent seems to be the set of laws listed in Deuteronomy 5 (vv. 6–21).

The Meaning of Davar

The noun דָּבָר (davar)—the singular of devarim—is one of the most common nouns in biblical Hebrew, appearing over one thousand times; it has a wide range of meanings, from “word” to “matter” or “thing.”[5] But what does עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, the ten devarim, mean in this context?

Statements/Words (Logoi)

The Septuagint translation (LXX, 3rd cent. B.C.E.) of Exodus renders עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים as “the ten words/statements” (tous deka logous; τοὺς δέκα λόγους). LXX to Deuteronomy 10:4 renders it identically. In Deuteronomy 4:13, however, the translator uses the synonymous “the ten words” (ta deka rhêmata; τὰ δέκα ῥήματα).

Josephus (37 CE – ca. 100 CE) also refers to them using the term logos, “word/statement.” While he does not call them “the ten statements,” Josephus does label each of them with ordinal numbers: “the first statement (logos) …; the second…”.[6]

Similarly, the Peshitta (the Syriac Bible) translates the phrase as עשרא פתגמין “ten words/statements”[7] and even uses this term in important early manuscripts as the heading to Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5, where the phrase does not appear.[8]

Coining the Term “Decalogue”

Clement of Alexandria (ca. 150 – 215 C.E.) and the Gnostic writer Ptolemy (2nd century C.E.) in his Letter to Flora—early Christian authors writing in Greek—built upon the Septuagint’s designation and coined the term, hê dekalogos, apparently a nominalized feminine singular adjective, meaning something like “the ten-statemented thing.”[9] From this point on, “The Decalogue” (hê dekalogos) became the preferred term in many Greek sources.

Commandments (Entolai)

Philo of Alexandria (ca. 20 B.C.E. – 50 C.E.), who knew the Bible in Greek rather than Hebrew, echoes and even expands upon the Septuagint translation by calling the Decalogue “the ten statements or oracles” (tous deka logous ê khrêsmous; On the Decalogue 32). Philo then adds that these ten statements are “in reality laws (nomous) or statutes (thesmous).”[10] Thus, Philo understands the phrase to mean “The Ten Commandments” even if this is not his literal rendering.

In his Epistle to the Romans, Paul applies another Greek term for laws, entolê—which the Septuagint employs consistently to translate Hebrew mitzvah, “commandment”—to the rules of the second part of the Decalogue:

Romans 13:9 For, “You shall not commit adultery; you shall not murder; you shall not steal; you shall not covet,” and any other commandment (entolê), are summed up in this word (Lev 19:18): “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.”[11]

Likewise, in the Synoptic Gospels, when Jesus expounds on most of the Decalogue[12] he uses the term entolê.[13] But these New Testament texts do not use any distinctive appellation to refer to the Decalogue.[14] It was Origen (ca. 185–253) who was the first to label the unit “The Ten Commandments” (αἱ δέκα ἐντολαί; hai deka entolai),[15] using the New Testament word entolê, “commandment.”

Ten Commandments Enters Latin

The equivalent expression in Latin also survives in Rufinus’s translation of Origen’s Homily on Exodus (translated between 403 and 405 C.E.): decem mandatorum legis “The Ten Commandments (mandata, gen.) of the law.”[16] Augustine (354 – 430 CE) uses a nearly synonymous term, decem praecepta,[17] from praecipio “to give rules or precepts…, to advise, admonish, warn, inform, instruct, teach; to enjoin, direct, bid, order, etc.”[18] The Vulgate’s decem verba “the Ten Words,” Augustine’s decem praecepta “the Ten Precepts,” and decalogus (borrowed from Greek) “the Decalogue/Ten Statements” were regularly used in Latin thereafter.

Divine Utterances (Dibberot)

While the biblical term “the ten devarim” is used in rabbinic literature, especially in the Mishnah,[19] many later Jewish texts, including the Babylonian Talmud, typically call the Decalogue עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְּרוֹת (aseret hadibberot) “the ten dibberot.” The latter term is the plural of dibber,[20] which likely means “divine word” and often appears in rabbinic literature, especially in reference to the Decalogue. Jastrow translates it as “revelation.”

The word dibber already appears in the Bible:

ירמיה ה:יג וְהַנְּבִיאִים֙ יִֽהְי֣וּ לְר֔וּחַ וְהַדִּבֵּ֖ר אֵ֣ין בָּהֶ֑ם כֹּ֥ה יֵעָשֶׂ֖ה לָהֶֽם׃

Jer 5:13 The prophets shall prove mere wind for the word is not in them; thus-and-thus shall be done to them!

Given that this word is a hapax, namely that it appears only once in the Bible, it is difficult to define it precisely. Some see it as specifically divine speech, in keeping with the rabbinic usage:

“word of God”—HALOT, LXX (λόγος κυρίου; logos kuriou)

“divine word”— German Gesenius, newest edition (“Gotteswort”)

“[their] false prophecy”—Targum Jonathan (וּנְבוּאַת שִׁקְרְהוֹן; u-nevuat shikrehon)

“the holy [=prophetic] spirit”—Radak (R. David Kimchi; רוח הקדש)[21]

Thus, the meaning of dibber as “divine word” in rabbinic literature may have biblical precedent. Nevertheless, while the context in Jeremiah certainly allows this more specific understanding of dibber, it does not compel it. Others see dibber here as just a word for “speech” (Clines) or “speaking” (BDB).

Why Change the Hebrew Term?

Unlike the Greek and Latin texts surveyed above, the rabbis, also writing in Hebrew, could simply have used the term devarim. Why did they exchange it with dibberot?

Mayer Gruber, Professor Emeritus of Bible from Ben-Gurion University, suggests that the change was a polemic against Christians who privileged the status of only these ten laws above all other Torah laws.[22] Accordingly, the post-Mishnaic rabbis chose to employ “the ten dibberot (utterances)” because it did not refer to commandments and therefore did not favor the Decalogue as superior to the other mitzvot (the position of these early Christians). But another possibility is that the rabbis found devarim “statements” too vague and replaced it with the term dibberot, which specifically referred to divine utterances.

The Problem with “the Ten Commandments” in Rabbinic Judaism

As for “the ten devarim”—which still appears in rabbinic literature—the rabbis would not have understood this as “Ten Commandments.” First, the opening verse is not a command:

שמות כ:ב אָֽנֹכִ֖י֙ יְ־הֹוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֑֔יךָ אֲשֶׁ֧ר הוֹצֵאתִ֛יךָ מֵאֶ֥רֶץ מִצְרַ֖יִם מִבֵּ֣֥ית עֲבָדִ֑͏ֽים׃

Exod 20:2 I YHWH am your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, the house of bondage.[23]

Nevertheless, Jewish tradition considers this to be the first dibber “divine utterance,” as may be seen in the many synagogue plaques that begin with it.[24]

Further, Judaism does not limit the number of commandments coming from the Decalogue to ten. In his highly influential tabulation of the 613 mitzvot (commandments), Moses Maimonides (1138–1204) derives fourteen commandments from the Ten Divine Utterances—thirteen mitzvot from Exod 20:2–17 and one additional mitzvah from Deuteronomy 5:6-21.[25]

Which Translation is Correct?

Mayer Gruber points to the fact that in various biblical passages, davar refers to a commandment (מצוה).[26] For example, in Exodus’s covenant ceremony, NJPS translates:

שמות כד:ג וַיָּבֹ֣א מֹשֶׁ֗ה וַיְסַפֵּ֤ר לָעָם֙ אֵ֚ת כָּל־דִּבְרֵ֣י יְ־הוָ֔ה וְאֵ֖ת כָּל־הַמִּשְׁפָּטִ֑ים וַיַּ֨עַן כָּל־הָעָ֜ם ק֤וֹל אֶחָד֙ וַיֹּ֣אמְר֔וּ כָּל־הַדְּבָרִ֛ים אֲשֶׁר־דִּבֶּ֥ר יְ־הוָ֖ה נַעֲשֶֽׂה׃ כד:ד וַיִּכְתֹּ֣ב מֹשֶׁ֗ה אֵ֚ת כָּל־דִּבְרֵ֣י יְ־הוָ֔ה...

Exod 24:3 Moses went and repeated to the people all the commands of YHWH and all the rules; and all the people answered with one voice, saying, “All the things that YHWH has commanded we will do!” 24:4 Moses then wrote down all the commands of YHWH…

Accordingly, Gruber suggested that “Ten Commandments” is the best translation of the biblical term aseret hadevarim, and indeed, it is the common translation in English (see appendix). Nevertheless, Gruber’s reasoning is not definitive. Very often, devarim simply refers to statements.

For example, Abraham’s servant says to Rebecca’s brother, Laban (Gen 24:33), לֹ֣א אֹכַ֔ל עַ֥ד אִם־דִּבַּ֖רְתִּי דְּבָרָ֑י “I will not eat until I have told my tale [literally: spoken my words (devarim)].” He then tells a long story (vv. 34–49) with no commands. Even in the singular, davar may be employed as a collective noun to refer to a set of words; this usage is especially obvious in the collocation דְּבַר־יְ־הוָה, the “davar (singular, as a collective noun) of YHWH,” often introducing prophetic oracles of varying sizes.

These typical uses of davar thus suggest that עשׂרת הדברים may be rendered “the ten statements,” following the LXX, the Peshitta, and some early Christian texts. This expansive sense of the word, rather than the narrower “commandments,” may better reflect the nature of the text and the more common usage of devarim in the Bible.

The Problem of Using “The Ten Commandments” as a Term in US Law

The discussion here has implications for American law. It is likely that in the near future, several laws, such as the 2023 Texas law (proposed, but not yet passed) that mandates the posting of The Ten Commandments in every public-school classroom,[27] will be considered by the Supreme Court.

Last year, in its Kennedy v. Bremerton decision concerning public prayer at the end of a public school football game, the court reversed the 1971 Lemon v. Kurtzman decision that insisted on a three-pronged test for the validity of such public displays of religion,[28] instead finding that public displays of religion need to be adjudicated according to whether the practice is supported by “history and tradition.”[29]

Thus, the term “Ten Commandments”—a term that the Texas legislation takes as normative, insisting that it be included in all classroom postings—must be examined on the basis of its history and doctrinal implications. But “history and tradition” do not provide clear, unambiguous guidelines for how the text of the Decalogue should be titled and presented.

First, the texts of Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5 differ,[30] so which is the official text? Although it sounds academic and somewhat formal, it would be more precise to speak of Exodus 20:2–17 and Deuteronomy 5:6–21 as “the Exodus Decalogue” and “the Deuteronomy Decalogue,” respectively.

Second, as noted, Jewish tradition sees fourteen commandments as opposed to ten. Indeed, what Judaism considers as the First Statement is, at best, listed as a prologue in the abbreviated lists of the Ten Commandments that some in the United States have sought to display in public. Often the statement does not appear in such lists at all.

Third, the different numbering systems of commandments in the Reformed and Anglican Churches (and other non-Lutheran Protestants) as compared to the Roman Catholic and Lutheran Churches cannot be reconciled.[31] Employing a version of the Ten Commandments based on the Reformed and Anglican traditions would necessarily result in the promotion of these forms of Christianity at the expense of both other Christian denominations and other religions that venerate these same sources in incompatible ways. So even if we could agree on what to call it, there can be no universally agreed-upon counting.[32]

Thus, the term “The Ten Commandments” is problematic from an American law perspective, and the Court must reject any legislation that relies on or mandates the term.[33]

Appendix

The Ten Commandments Enters English

In English, the concept of “Ten Commandments” is first attested in Aelfric’s (ca. 955 – ca. 1010) The Homily for the First Sunday in Lent with the Old English words týn bebodu, “ten decrees/orders/commands.”[34] As Aelfric’s text paraphrases the main premises of Augustine’s discussions on the Decalogue,[35] týn bebodu is most likely a translation of Latin decem praecepta used by Augustine and subsequent theologians.

With the Norman Conquest (1066) and the transformation of Old into Middle English, bebodu was abandoned in favor of a term of French origin, “commandemens” or “comandmentes.”[36] The expression became an established part of late Medieval English culture, appearing as “þe Ten Commandemens” in a poem preserved in the 13th-century Kildare Manuscript.[37]

|

God commandid [M]oysay þat he ssold wend and prech, þat was in þe hil of Syna[i], Hou he ssold þe folk tech, And to ssow ham Godis defens, Boþe to ȝung and to olde, Of þe Ten Commandemens; Whos wold be sauid, ham ssold hold. |

God commanded Moses that he should go and preach, that was in the hill of Sinai, how he should teach the folk, And to show them God’s prohibition, Both to young and old, Of the Ten Commandments; Who would be saved, them should hold. |

This is also the rendering in “Prick of Conscience” from the second quarter of the 14th century, possibly the most popular English poem prior to the invention of the printing press:

|

For þe haythen men at þat grete assys Sal þan be halden als men rightwys To regard of þe fals Cristen men þat wald nought kepe þe comandmentes ten, Bot spende[d] þair fyve wittes in vayne. |

For the heathen men at that great test Shall then be held as men righteous Compared with the false Christian men That would not keep the commandments ten, But used their five senses in vain. [38] |

The Decalogue Replaces the Cardinal Sins

The Dominican theologian Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), followed by the Council of Trent (1545–1563), turned the Decalogue into a compendium of natural law that had been confirmed by Christ. French educator and reformer Jean Gerson (1363–1429) made it the foundation of Christian ethics.[39] As the late British historian John Bossy (1933–2015) has shown, these developments resulted in the Ten Commandments replacing the Seven Deadly or Cardinal Sins—Pride, Envy, Wrath, Avarice, Gluttony, Sloth, and Lechery—as the core of the moral system of Christianity.[40]

From this period on, they were taught as what Bossy calls “a necessary preliminary to the knowledge of Grace provided by the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Sacraments.”[41] It is likely that the Decalogue’s growing prestige in the period leading up to the Reformation helps explain the fact that it would be invoked in an increasingly standardized and memorable way.

The “Ten Commandments” in Early English Bible Translations

The translation “The Ten Commandments,” one of the possible renderings of the Latin decem praecepta, became entrenched in English as a result of its prominence in didactic poetry, catechisms, theological treatises, and popular pamphlets, as well as liturgical compendia like the Bishops’ Book of 1537, Sterne and Hopkins’ 1549 hymnal (The Whole Booke of Psalmes), and the Book of Common Prayer (since its first edition in 1549).[42] Nevertheless, it took somewhat longer for it to become standard in English-language Bibles. Here, for example, is a survey of the main translations of Exodus 34:28 in English from the 11th to the 17th century:

Old English Heptateuch (11th century): … and wrat Þa tyn word Þe Drihten him bebead.[43]

Wycliffe Bible (1382): … and he wroot in tablys ten wordis of the boond of pees.

Tyndale Bible (1530): … And he wrote in the tables the wordes of the couenaunt: euen ten verses.[44]

Coverdale Bible (1535): … And he wrote in the tables the wordes of the couenaut, euen ten verses.

Matthew Bible (1537): … And he wrote in the tables the wordes of the couenant: euen ten verses.

Great Bible (1539): Ex 34:28 … And he wrote vpon the tables the wordes of the couenaunt, euen ten verses.

Geneva Bible (1560): … and he wrote in the Tables *the wordes of yͤ couenant, euen the ten qcommandements. * Deu 4,13. qOr, wordes.[45]

Bishop’s Bible (1568): … and he wrote vpon the tables the wordes of the couenaunt, [euen] ten commaundementes.[46]

Douay-Rheims Bible (1609): … and he wrote in the tables the wordes of the couenant ten.[47]

King James Version (1611): … And he wrote upon the Tables the words of the couenant, the ten †Commandements. †Hebr. words.[48]

This comparison shows that the Geneva Bible of 1560, the Bible translated in John Calvin’s Geneva by exiles from the England of Queen Mary I (r. 1553–1556), was the first version to make use of the expression “the Ten Commandments.”[49] The term subsequently appeared in the Bishop’s Bible of 1568 (commissioned during the reign of Elizabeth I to supplant the Geneva Bible) and was ultimately employed in the King James Version of 1611. It has remained a fixture in English Bible translations ever since.[50]

That these translators did not understand “The Ten Commandments” as a literal translation is confirmed by the marginal notations on the verse in both the Geneva Bible and the King James Version, which indicate that “words” was considered a more literal rendering of the original Hebrew.

So why did Reformation biblical translators employ this phrase that was on its face less accurate than “The Ten Words” or “The Ten Verses,” and, what’s more, had been imported from Catholic writings? They were most likely influenced by the entry of the term “The Ten Commandments” into common English usage.

“The Ten Commandments” did not merely refer to precepts that would lead to deeper Christian beliefs, like the Latin decem praecepta “ten precepts” that preceded it: In its influential appropriation by the Geneva and King James Bibles, “the Ten Commandments” designated the unattainable standard upon which the Calvinist idea of the total depravity of mankind rested.[51]

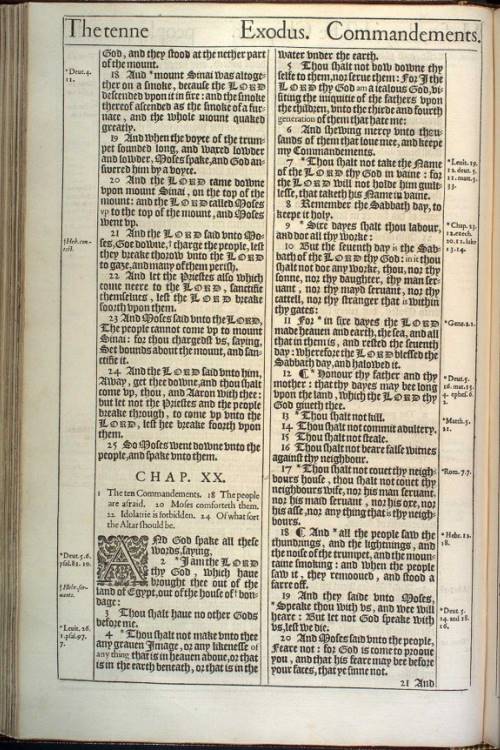

Running Headers—Reinforcing the prominence of this term was its deployment in key places on the physical page: The topical running heads at the top of the page. Such topical running heads appeared in the 1534 French Bible of Lefèvre and the 1535 French Olivétan Bible.[52]

Matthew Bible—The headers made their first appearance in English in the 1537 Matthew Bible, which has “The. X. Preceptes.” printed as a running head above Exodus 20.

Geneva Bible—In the 1583 printing of the Geneva Bible, “The ten Commandements” was printed as a running head at the top of the pages of both Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5-6 in large letters; the term did not appear in this way in the 1560 Geneva Bible or in the 1568 Bishop’s Bible.[53]

King James Bible—The King James Version of 1611 had “The tenne Commandements” as a running head for Exodus 20.

These running heads helped the term become further entrenched in English.

|

|

| Geneva Bible 1583 | King James Bible 1611 |

Chapter Summaries—Medieval Latin Bibles listed chapter contents (casus summarii),[54] which regularly indicated the appearance of the Ten Words or the Decalogue at the beginning of the relevant biblical sections in that manuscript.[55] Some manuscripts also place a number before each of the ten precepts in the text proper of Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5. The use of chapter summaries continued in the Reformation period; in keeping with this practice, the King James Bible of 1611 listed “The ten Commandements” in the summary of contents at the beginning of both Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5, the first usage of the term in this way in an English Bible.[56]

Running heads and chapter summaries had become standard in English Reformation printed Bibles, with these and other paratexts—namely elements added to the page that are not part of the biblical text—providing convenient assistance for a new population of lay readers. Simultaneously, textual margins were now a prominent venue for legitimating a popular term that had barely begun to appear in the biblical text itself. As a result of these innovations by the printers, “The Ten Commandments,” an imprecise or even problematic term, became standard in English.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 25, 2023

|

Last Updated

February 10, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Marc Zvi Brettler is Bernice & Morton Lerner Distinguished Professor of Judaic Studies at Duke University, Dora Golding Professor of Biblical Studies (Emeritus) at Brandeis University, and a research professor at Hebrew University. He is author of many books and articles, including How to Read the Jewish Bible (also published in Hebrew), co-editor of The Jewish Study Bible and The Jewish Annotated New Testament (with Amy-Jill Levine), and co-author of The Bible and the Believer (with Peter Enns and Daniel J. Harrington), and The Bible With and Without Jesus: How Jews and Christians Read the Same Stories Differently (with Amy-Jill Levine). Brettler is a cofounder of TheTorah.com.

Prof. Jed Wyrick is Professor of Comparative Religion and Humanities at California State University, Chico. He holds a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from Harvard University and is the author of The Ascension of Authorship: Attribution, Textualization, and Canon Formation in Jewish, Hellenistic, and Christian Traditions (Cambridge, 2004).

Essays on Related Topics: