Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Human Face on the Divine Chariot: Jacob the Knight

A masorah figurate micrographic illustration of the faces of Ezekiel's four creatures in a 13th cent. Ashkenazy Bible; British Library (Or. 2091), fol. 203. Top panel.

The book of Ezekiel opens with the famous vision of YHWH’s chariot,[1] which is drawn by four beasts, each of which has four faces:

יחזקאל א:י וּדְמוּת פְּנֵיהֶם פְּנֵי אָדָם וּפְנֵי אַרְיֵה אֶל הַיָּמִין לְאַרְבַּעְתָּם וּפְנֵי שׁוֹר מֵהַשְּׂמֹאול לְאַרְבַּעְתָּן וּפְנֵי נֶשֶׁר לְאַרְבַּעְתָּן.

Ezek 1:10 Each of them had a human face [at the front]; each of the four had the face of a lion on the right; each of the four had the face of an ox on the left; and each of the four had the face of an eagle [at the back]. (NJPS)

Artists have long tried to capture this image, whether in paintings or in illustrated Bibles. In doing so, however, Jewish scribes had to consider some halakhic problems.

The Prohibition to Draw the Four-Faced Creature of the Chariot

One of the first commandments in the Decalogue is not to create images for the sake of worship.[2] Rabbinic literature understands Exodus 20:20[*23], immediately following the Decalogue, as broadly prohibiting the creation of certain images, even for decoration (Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, “BaChodesh” §10):

"לֹא תַעֲשׂוּן אִתִּי" – רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל אוֹמֵר: לֹא תַעֲשׂוּן דְּמוּת שַׁמָּשַׁי, הַמְּשַׁמְּשִׁין לְפָנַי בַּמָּרוֹם. לֹא דְּמוּת מַלְאָכִים, וְלֹא דְּמוּת אוֹפַנִּים, וְלֹא דְּמוּת כְּרוּבִים.

“Do not make with me” (Exod 20:20)—Rabbi Ishmael says: “You shall not make a likeness of My servants who serve before Me in heaven, nor the likeness of angels, nor the likeness of the ophanim, nor the likeness of the cherubim.”

In its discussion of this prohibition, the Babylonian Talmud notes that in relation to declaring the new Hebrew month, Rabban Gamliel used images of the moon to show witnesses claiming to have seen the new moon, to ask them what exactly they saw. Shouldn’t this be prohibited, the Talmud asks? In response, the 5th generation Babylonian Amora, Abaye, modifies the law to refer to the four-faced creature of Ezekiel’s divine chariot (b. Avodah Zarah[3] 43a–b):

אמ[ר] אביי: לא אסרה תורה אלא כדמות ארבעה פנים בהדי הדדי.

Abaye said: “The Torah only prohibits making an image like that of the four faces in one.”

Thus, the halakhic precedent was set for making the four creatures as standalone images. Nevertheless, the Talmud brings up a problem with the human face.

The Human Face Problem

The Talmud challenges the implications of Abaye’s answer:

אלא מעתה פרצוף אדם לחודיה לישתרי? אלמא תניא כל הפרצופין מותרין חוץ מפרצוף אדם!

If so, then just making a human face should be permitted? But does it not teach [in a Tannaitic text]: “All the faces are permitted except a human face”?!

The Talmud then answers that human faces are an exception. Humans are made in the image of God (Gen 1:26-27), so making a human face would be like making the face of God:

אמ' רב הונא בריה דרב [יהושע]: מפירקיה דאביי שמיע לי 'לא תעשון אִתִּי' 'לא תעשון אוֹתִי' אבל שאר שמשין שרי.

Rav Huna son of Rav Joshua said: “I heard in the seasonal lectures of Abaye, that (Exod 20:20) “do not make with me” [should be understood as] “do not make me” [i.e., something that looks like me], but [making images of] all other [heavenly] servants [of God] are permissible.”

The halakha, then, is that three out of the four beasts may be drawn with faces. Thus, Rashba (Rabbi Solomon ibn Aderet of Barcelona, d. 1310) wrote in a responsum to a questioner who wanted to know whether it was permissible to make an image of a lion, since it is one of the four faces of the chariot’s beasts (Responsa Rashba 1:167):

והעושה צורת פנים כצורת החיות שעושה לה דמות ארבע פנים אלו הרי זה אסור אבל אחת מהן לבד לא... ולפיכך צורת אריה ונשר ושור כל אחת לעצמה מותר לעשותה.

Creating a face like the form of the four creatures, i.e., making one figure with those four faces, is forbidden, but creating one of them alone is not… and that is why creating the form of the lion, the eagle and the ox, each on its own, is permitted.[4]

This prohibition explains why Jewish illustrated Bibles contain various depictions of Ezekiel’s beasts as separate creatures, each with its own face and form, though some artists avoid drawing the human face in keeping with the Talmudic prohibition.[5]

The Masorah Figurate

The Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bibles is accompanied by sets of notes in the margins. The notes are meant to prevent scribal errors, helping to preserve the biblical text precisely. These notes are typically written in micrography, “tiny letters,” in between, above, and below the columns of the text.[6]

In many medieval manuscripts, scribes wrote out the Masoretic notes in the form of pictures, what scholars refer to as masorah figurate (“Figurative/Decorative Masorah”).[7] This type of art, unique to Jewish texts, creates the outlines of miniature ornamentation in biblical manuscripts. Artists use this form in margins, carpet pages (full pages with only designs), opening word panels, verse counts, and colophons (brief statements by authors or scribes at the end of books).

The practice was controversial, and no less an authority that R. Judah HeChasid (ca. 1150–1217) argues against it (§709):

מי שמשכיר סופר לכתוב מסורת בספר עשרים וארבע ספרים יעשה תנאי עם הסופר שלא יעשה המסורת צייורים עופות וחיות או כאלו ולא שום צייורין מה שהתחילו המסורת לכתוב בספר עשרים וארבעה ספרים כי הראשונים היו בקיאין במסורת לכך כתבו בספרים ואם יעשה צייורים איך יראה?

One who hires a scribe to write the masorah for the 24 Books (i.e., the Bible) should make a condition with the scribe that he should not make the masorah into drawings of birds or beasts or a tree or into any other illustration as people have started doing for the masorah in the 24 Books. For the ancient scribes were experts in the masorah, and that is why they wrote these notes, but if [a scribe] writes them in the form of pictures, how will [the reader] be able to see [and read the masorah]?” [8]

Despite this prohibition, the practice remained popular in Ashkenazi circles. Such images are especially popular on the page depicting Ezekiel’s vision of the chariot, where many scribes depicted the four creatures.

Depicting the Four Creatures

Most Jewish depictions of the four creatures follow the Christian convention of portraying the three beasts with wings, and rendering the human figure as an angel.[9] For example, in a masorah figurate decoration from an Ashkenazi Bible known as the “Yonah Pentateuch,”[10] produced in the second half of the thirteenth century, all the creatures are winged.

The human is winged and has the word אדם “human” on it, but neither the figure nor the face looks all that human. Yonah Pentateuch. London, British Library Add. 21160, fol. 192v.

The human is winged and has the word אדם “human” on it, but neither the figure nor the face looks all that human. Yonah Pentateuch. London, British Library Add. 21160, fol. 192v.

One exception to this style of portrayal is in another Ashkenazi Bible from the second half of the thirteenth century, now housed in London’s British Library (Or. 2091), where we find a unique micrographic depiction of the creatures In this manuscript, each pages has three columns of Hebrew text.[12] On the page in question (fol. 203a), the first column (from right to left) contains the final verses of Isaiah (66:21–24), and the next two columns contain the opening of Ezekiel (1:1–23).[13]

Instead of the common approach in other Hebrew illuminated manuscripts, where two creatures are illuminated on the top and two on the bottom of the page (as in Christian art),[14] this manuscript has two separate portrayals of all four creatures, set in a single row.[15] The upper masorah margin, from right to left, depicts the upper bodies of an eagle, a man wearing a helmet and chain mail, a lion, and an ox (see main image above).

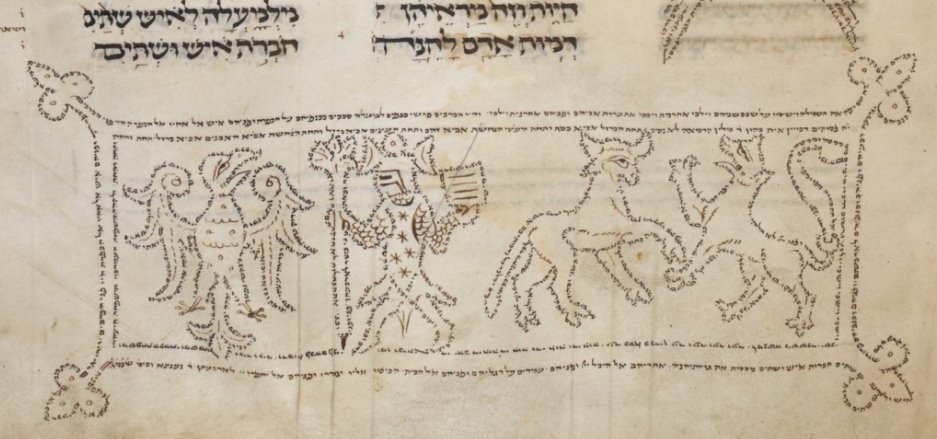

The bottom masorah depicts a rectangular frame enclosing the full bodies of Ezekiel’s creatures in a different arrangement: the lion on the right is facing the ox, while the man, in full armor holding an object in each hand, is facing the eagle, whose wings are spread.[16]

A masorah figurate micrographic illustration of the faces of Ezekiel's four creatures in a 13th cent. Ashkenazy Bible; British Library (Or. 2091), fol. 203. Bottom panel.

A masorah figurate micrographic illustration of the faces of Ezekiel's four creatures in a 13th cent. Ashkenazy Bible; British Library (Or. 2091), fol. 203. Bottom panel.

In both pictures the human is depicted as a knight, complete with armor, helmet, and weapons, rather than an angel. This depiction of the human figure as a knight is unique. While such a depiction has halakhic utility, since the helmet allows the artist to avoid drawing a face, the choice of imagery here has further meaning when we understand its implications in medieval rabbinic thinking, especially in the world of the 12th and 13th century German pietists known as Hasidei Ashkenaz.

Jewish Knights in Medieval Times

Warriors, especially knights, are portrayed elsewhere in Ashkenazi manuscripts, both in miniature paintings and in micrography, as both Christian and Jewish figures.[17] Indeed, some Jews were permitted to carry weapons, and the arms indicated a high social status.[18]

In this image, the knight is dressed in a surcoat, a sleeveless garment worn over a chainmail hauberk (i.e., a long mail shirt with long sleeves), which became part of a knight’s apparel during the first half of the thirteenth century and continued to be worn for approximately a hundred years. The purpose of the surcoat was to protect the chain mail from the weather and to identify men in battle, since their faces were covered by helmets. Each army had its own heraldic sign, and its display on the surcoat clearly indicated the side to which the warrior belonged.[19] In this case, the figure’s heraldic symbols are shaped like stars.

In this image, the knight is wearing a large helmet with a crest of a round object and two crescents.[20] In tournaments, but never on the battlefield, knights of a higher class, such as cavalrymen, wore these great helms,[21] which covered the entire face except for the eyes.[22] Unlike warriors engaged in combat, who could earn their knighthoods regardless of their social status, only nobles competed in tournaments.[23] Choosing to portray the knight in the Jewish manuscript as a tournament participant hints at his aristocratic position.

Jews in Tournaments

R. Moshe ben Elazar HaCohen of Koblenz (ca. 1250–1329), a sage connected to the German pietists, objected to any Jewish involvement in tournaments, even as spectators. He writes in his Sefer Hasidim:

וכי יקרא בעירך קגיגייאות של עכו״ם כגון מורלאנגא וטורניי השמר לך לבל תראם.

And if contests of non-Jewish knights appear in your city, such as a mêlée or a tourney, be careful not to go watch them.[24]

Nevertheless, it seems clear that Jews did attend tournaments, and may even have participated in them. A responsum from 12th century German sage, Rabbi Yoel HaLevi, included in his son’s work called Sefer Ra’aviah,[25] shows that Jews were involved in tournaments. The responsum concerns a quarrel regarding a set of chain mail (§1027):

ראובן תבע שמעון לדין ואמר באתי אליך להשאיל שריונים להחזיר לך לסוף שבועים או כ"ו דינר קולוני' ישנים והנחתי לך משכון עליהם. וכשחזרתי מן הטורניר אמרתי לך שאבד[ו] השריונים. והוצרכתי לאותו משכון למקצתו. ונתתי לך י' דינר קולניש מטבע חדש בחשבון...

Reuben took Shimon[26] to court and said: “I came to you to borrow chainmail, and to return it to you at the end of two weeks or to pay 26 old Colognian denarii,[27] which I left with you as collateral. But when I came back from the tournament, I said to you that I lost the chainmail, but that I needed part of the money I gave to you as collateral. So I gave you ten new Colognian denarii as a partial payment…”

The responsum itself is about the technical question connected to the value of coinage that shifts over time. For our purposes, it is sufficient to note that Shimon owns chainmail and Reuben needs to use it for a tournament. Whether Reuben attended the tournament is unknown,[28] but he was certainly involved in the tournament in some way.[29] This strengthens the likelihood that the knight in the illustrated Bible is Jewish; specifically, I believe it is the patriarch, Jacob.

Jacob the Knight

Jacob’s blessing of Joseph contains the line:

בראשית מט:כד וַתֵּשֶׁב בְּאֵיתָן קַשְׁתּוֹ וַיָּפֹזּוּ זְרֹעֵי יָדָיו מִידֵי אֲבִיר יַעֲקֹב...

Gen 49:24 Yet his bow stayed taut, and his arms were made firm, by the hands of the avir Yaakov…

Avir Yaakov means “Mighty One of Jacob,” and is a reference to God.[30] The word אביר meant “knight” in medieval Hebrew, inspiring the 13th century sage, Rabbi Chaim Paltiel of Falaise to offer an alternative interpretation of the verse:

מידי אביר יעקב. כלומר מי גרם לו כל הגדולה הזאת והכבוד הזה זה אביר יעקב, כלומר זהו יעקב שהוא גבור.

“By the hands of avir Yaakov”—Meaning: Who caused him all of this might and honor? It is Avir Ya’akov, that is, Jacob, the hero/champion.[31]

In keeping with this imagery, I suggest that the knight in this micrography decoration is Jacob, pictured here as Jacob the Knight.[32] This would be in line with yet another image from this period which adorns the initial panel of the piyyut El Mitnase for Shabbat Shekalim, where Jacob is represented as one of the four creatures (but not as a knight).[33]

Illustration of the four creatures for the piyyut Mitnase. The human on the top left corner is Jacob.

Illustration of the four creatures for the piyyut Mitnase. The human on the top left corner is Jacob.

According to Katrin Kogman-Appel of Münster Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität, this image from the Leipzig Mahzor reflects ideas found in the esoteric writings of Hasidei Ashkenaz, especially those of Rabbi Elazar of Worms, regarding a vision of Jacob on the Throne.[34]

Jacob’s Face on the Divine Throne

The story of Jacob’s dream in Bethel describes a stairway or ladder that angels climb up and down:

בראשית כח:יב וַיַּחֲלֹם וְהִנֵּה סֻלָּם מֻצָּב אַרְצָה וְרֹאשׁוֹ מַגִּיעַ הַשָּׁמָיְמָה וְהִנֵּה מַלְאֲכֵי אֱלֹהִים עֹלִים וְיֹרְדִים בּוֹ.

Gen 28:12 He had a dream; a stairway was set on the ground and its head reached to the sky, and angels of God were going up and down on it.

Hebrew does not have the gender-neutral term “it,” and in this verse “it” does not unambiguously refer to the ladder. Thus, rabbinic midrash understood the phrase “its head,” as “his head,” Jacob’s head, which can be found in heaven. This motif eventually leads to a new understanding of the story: the reason the angels were climbing up and down was to see the human being, Jacob, who had the same face as that carved on the holy throne.

This tradition is reflected, e.g., in the Fragmentary Targum Yerushalmi:

וחלם והא סולמא קביע בארעא ורישיה מטי עד צית שמיא והא מלאכיא דילוון יתיה מביתיה דאבוי סליקו למבשרא למלאכי מרומא למימר אתון חמון ליעקב גברא חסידא דאיקונין דידיה בכורסי דיקרא דהויתון מתחמדין למיחמיה יתיה והא מלאכין קדישין מן קדם יי סלקין ונחתין ומסתכלין ביה.

He dreamed, and there was a ladder set in the ground whose head went up to the heavens, and the angels that were accompanying him from his father’s house went up it to announce to the angels up high, saying: “Come look at Jacob, the righteous man, whose visage is upon the precious throne, and you have always wanted to see him.” So the holy angels left the presence of the Lord going up and down to look at him.[35]

The motif of Jacob’s face inscribed on the throne is not identical to the idea of Jacob as the human face of the creature on the chariot. Nevertheless, Elliot Wolfson notes how the two motifs were connected in the writings of Hasidei Ashkenaz, where the chariot and the throne were seen as coterminous, and Jacob’s face appearing both etched upon the throne and as the face of the creature.[36]

Understanding the masorah figurate knight as Jacob explains another set of features in the bottom image.

A Torah in One Hand

In his left hand, the knight in this micrography decoration holds a rectangular object. This cannot be a shield: it is too small and is not held like a shield.[37] An image in the Leipzig Mahzor, produced in Worms around 1310 provides a clue to this object’s identity: there Jacob, whose image is carved on the heavenly throne, is holding a book, characterizing him as a scholar.[38]

In this light, the horizontal lines on the object in the knight’s hand can be understood as writing, with the object some sort of document or a writing tablet.[39] An image of Jacob holding a book accords with his identification as a tam, an innocent [scholar] seated in a tent and studying—the typical rabbinic understanding of Genesis 25:27.[40]

In Rabbi Judah HeChasid’s Sefer Gematriot, a commentary on the Torah offering lists of numerical equivalences to biblical terms, the idea of Jacob’s image being engraved on the Throne is related to his (Jacob’s) study of the Torah:[41]

"יעקב איש תם," (בראשית כה:כז) וחקוק דמותו בכסא, זהו "תמים תהיה עם ה' אלהיך" (דברים יח:יג), לפי שהיה עוסק בתורה לילה ויום, דכתיב (בראשית לא:מ) "תדד שנתי מעיני" – שהיה מחלים עינייני התורה שהיה עוסק ביום, זהו (בראשית כח:טז): "ויקץ יעקב משנתו" ממשנתו, וזהו (תהלים א:ב) "ובתורתו יהגה יומם ולילה."

“Jacob was a perfect (tam) man” (Gen 25:27) and his face was carved on the throne, and this is the meaning of (Deut 18:13) “You shall be perfect (tamim) with the Lord your God.” For he would study Torah night and day, as it says (Gen 31:40): “and my eyes missed their sleep” for he would dream of the Torah topics he had studied that day. And this is what it means by (Gen 28:16) “And Jacob woke from his sleep (mishnato),” [he awoke] from his Mishnah study, and this is what it means (Ps 1:2): “And you shall recite it day and night.”

The micrography decoration makes use of this imagery of Jacob as Torah scholar and combines it with that of Jacob as a heroic knight.

Jacob’s Staff

In his right hand, the knight is holding what seems to be a long mace, probably of the type known as the “Gothic Mace,” where the flanges on the head were thick and pointed. This was a popular weapon of war and a secondary weapon in tournaments.

The mace was the weapon of choice for the militant churchmen, who sought to avoid the denunciation of those who “smite with the sword,”[42] and from the twelfth century onward it was also used as a symbol of authority. In time, a ceremonial mace appeared, which was similar to the mace in this micrography image: it was about as long as a human being was tall, heavily ornamented at the top, and often pointed at the bottom.[43]

The artist is likely associating the mace with Jacob’s staff, which Jacob mentions in his prayer to God before encountering Esau:

בראשית לב:יא ...כִּי בְמַקְלִי עָבַרְתִּי אֶת הַיַּרְדֵּן הַזֶּה וְעַתָּה הָיִיתִי לִשְׁנֵי מַחֲנוֹת

Gen 32:11 …For with my staff I passed over this Jordan; and now I am become two camps.[44]

In his Sefer Gematriot, R. Judah HeChasid used the numerological association of the word “with my staff” to identify Jacob:

"כי במקלי" בגמטריה "יעקב." [45]

“For with my staff” is numerically the same as “Jacob.”[46]

Moreover, staffs are often associated with images of power or rulership (see, e.g., Gen 49:10), and Jacob’s alternative name Israel (Yisrael), is related to the word serara “authority.”[47] Jacob, dressed as a knight and holding a staff, would reinforce his position as an authoritative character of higher rank than the other creatures.

The Pious Knight Is Jacob

Ivan Marcus contends that the writer of Sefer Hasidim sees the positive value of the knightly code of honor and valorous behavior, and implies that the Jewish pietist should behave like a chivalrous knight by serving the Lord fearlessly without expecting any reward.[48] This idea is illustrated by the knight in the picture, who is dressed in an authoritative and chivalric costume, but is not armed with lethal weapons.

The image of knights in Jewish writings is used to emphasize the more spiritual aspects of noble warriors, those qualities that reveal their heroic nature. This micrography decoration thus portrays the human figure, most likely Jacob, as a true, scholarly and pious knight of Torah, worthy to take his place as one of the carriers of God’s chariot, whose face, though covered in this picture, is engraved upon God’s own throne.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

June 3, 2022

|

Last Updated

December 11, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Sara Offenberg is an associate professor at the Department of the Arts at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. She holds an interdisciplinary Ph.D. (summa cum laude) from the Department of Jewish Thought and the Department of the Arts at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. She is the author of Illuminated Piety: Pietistic Texts and Images in the North French Hebrew Miscellany (2013) and Up in Arms: Images of Knights and the Divine Chariot in Esoteric Ashkenazi Manuscripts of the Middle Ages (2019). Between 2014-2017, Offenberg was co-editor of the journal Ars Judaica: The Bar-Ilan Journal of Jewish Art, and she is presently (since 2021) managing editor of Mabatim: Journal of Visual Culture. Her research focuses on chivalry and warriors in Hebrew manuscripts, German Pietists, Hebrew illuminated prayer books, and Jewish-Christian relations in medieval art and literature.

Essays on Related Topics: