Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Psychological Mechanisms that Protect Unreasonable Faith Claims

We have all experienced the futility of trying to change a strong conviction, especially if the convinced person has some investment in his belief. We are familiar with the variety of ingenious defenses with which people protect their convictions, managing to keep them unscathed through the most devastating attacks. But man’s resourcefulness goes beyond simply protecting a belief. Suppose an individual believes something with his whole heart; suppose further that he has a commitment to this belief, that he has taken irrevocable actions because of it; finally, suppose that he is presented with evidence, unequivocal and undeniable evidence, that his belief is wrong: what will happen? The individual will frequently emerge, not only unshaken, but even more convinced of the truth of his beliefs than ever before. Indeed, he may even show a new fervor about convincing and converting other people to his view.[1] – When Prophecy Fails, p. 3

The concept of Torah-Mi-Sinai, that God dictated the entire Torah word for word to Moses at Mount Sinai or during the wilderness sojourn, is a core faith claim (עיקר אמונה) in Orthodox Judaism. Putting aside the issues surrounding divine authorship and the implication of saying that God wrote a book, the idea that the Torah was written by any one hand during the “wilderness period” has been rejected by modern biblical scholarship. The alternate view, accepted by virtually all academic scholars of the Bible, is that the Torah is a composite document with multiple sources and redactions, composed over a long period of time, and even after it was compiled its text was not fixed.

Another central belief of Orthodox Judaism is that the events described in the Torah, like the ten plagues, the splitting of the Red Sea, and 2-3 million Israelites (600,000 males) wandering the Sinai wilderness for forty years eating manna from heaven are events that actually occurred in history. And yet, common sense would dictate that these stories are myths the Israelites told about their past, no different than the myths virtually all pre-modern religions and cultures tell about their past. Add to this the fact that the archaeological record contradicts many of the Bible’s claims, such as Joshua’s bringing down the walls of Jericho or the massive presence of Israelites in the Sinai wilderness.

Despite the overwhelming amount of evidence for the Torah as a composite document describing Israel’s mythic origins, the academic model has made little if any impact on the way Orthodox people study the Torah… even Modern Orthodox people. Why and how do so many Modern Orthodox individuals who participate in the modern world so fully, turn to fundamentalist apologetics in order to justify their belief in Torah-Mi-Sinai?

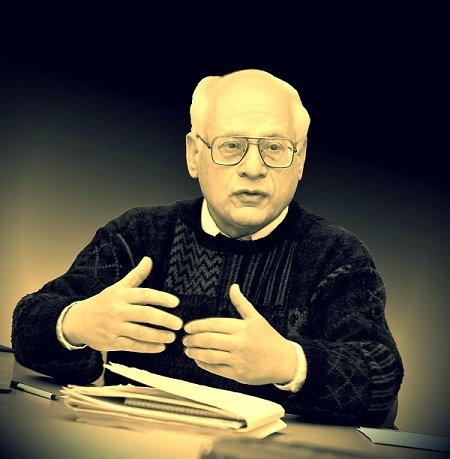

As a professor of psychology who grew up as an Orthodox Jew believing these very things—I am fascinated by this persistence or “tenacity” as I call it in my book.[2] What defense mechanisms do the Orthodox employ to counter the powerful evidence and arguments against Torah-Mi-Sinai? I think there are several at work.

Psychological Defense Mechanisms at Work

1. Claim the Position is Actually Plausible

Many deny that their belief is implausible. An example of this approach is the book by Lawrence Kelemen, Permission to Receive (Targum, 1996).[3] Kelemen tries to prove that it is not implausible, and that it is indeed plausible, to believe in Torah-Mi-Sinai; he is defensive rather than offensive. For example rather than disparaging archaeology in general, he uses it selectively to support his beliefs and ignores it when it doesn’t. He also uses the Kuzari “proof” in what appears to be a sophisticated way.[4]

Kelemen’s intended audience seems to be people from the yeshiva world who have had some exposure to biblical scholarship and have come to worry that their belief in Torah-Mi-Sinai is irrational. Thus, his book is designed to convince the readers that they don’t need to be ashamed about asserting their belief in Torah-Mi-Sinai.[5]

2. Dispute the Evidence behind the Academic Model

While some apologists for the traditional belief in Torah-Mi-Sinai try to prove the rationality of their Torah-Mi-Sinai claim, whether by logic or empirical evidence, other Orthodox Jews challenge the evidence against their belief and claim that the evidence for the composite nature of the Torah is weak. They often disparage the disciplines and methods used in the academic study of Bible and comparative religion. Thus, for example, one of the most influential thinkers in the Torah U’Madda world, Norman Lamm, former President of Yeshiva University, wrote the following in a Commentary symposium on the State of Jewish Belief:

Higher Criticism is far indeed from an exact science. The startling lack of agreement among scholars on any one critical view; …the many revisions that archaeology has forced upon literary critics; and the unfortunate neglect even by Bible scholars of much first-rate scholarship in modern Hebrew supporting the traditional claim of Mosaic authorship—all these reduce the question of Higher Criticism from the massive proportions it has often assumed to a relatively minor and manageable problem that is chiefly a nuisance but not a threat to the enlightened believer. (Lamm, 1966, 110).

3. Ad Hominem Arguments

Some employ ad hominem arguments against the proponents of the competing, challenging belief. They will assert that academic biblical scholars are unfamiliar with traditional rabbinic and medieval Jewish exegesis (which is sometimes the case, but there are numerous others who are well-versed in rabbinic and medieval biblical interpretation). If, say the believers, the biblical critics were aware of the traditional approaches to Bible study, they would accept Torah-Mi-Sinai.

Others have accused academic biblical scholars of being blinded by their evil inclinations, being anti-Semites, or being self-hating Jews. They ignore that although it is true that prior to the mid-twentieth century many leading Christian biblical scholars, such as Wellhausen, disparaged Judaism, the Christian biblical critics applied their methods of analysis to the New Testament as well as to the Hebrew Bible. Jon Levenson has noted, “[The] fact that historical criticism has undermined Christianity no less than Judaism . . . is too often ignored [by Jewish critics of modern biblical scholarship]” (p. 43).[6] These ad hominem arguments also overlook the fact that many archaeologists whose findings challenge the historical accuracy of biblical accounts, and indirectly the theory of Torah-Mi-Sinai, actually were motivated by a desire to corroborate the historical accuracy of the Bible and to support traditional doctrines rather than to discover evidence against them.

Moreover, even if the anti-Jewish argument held some truth in the past, it cannot be applied to the field as it is now, since a good number of contemporary biblical scholars who take for granted the composite nature of the Torah are strongly identifying, halakhically practicing, self-loving Jews.

4. The Argument that it is Beneficial to Believe in Torah-Mi-Sinai

Believers in Torah-Mi-Sinai often argue that the consequences of their belief system are positive whereas those of the alternative beliefs are negative. For example, they will claim that to deny Torah-Mi-Sinai will destroy morality, weaken Jewish identity, and lead to the assimilation of Jews and to the demise of Judaism.[7]

But, is this really true? How essential, if at all, is an Orthodox belief system in maintaining worthwhile Jewish communities in the United States that will perpetuate themselves? What beliefs/doctrines/dogmas are necessary to generate such communities? I admit that I do not have the answers to this question, but the claim that Orthodox dogma is a necessary condition needs to be explored empirically by sociologists who study Jewish religious communities and by historians of modern Jewry, and not be asserted as a self-evident truth. Moreover, even if dogma is necessary, should a community be built on falsehoods?

5. Avoidance

Many Orthodox, modern as well as Haredi, will avoid exposing themselves to the evidence and the arguments of scholarship. This reflects awareness that exposure might generate doubt, and because the consequences of doubt can be dangerous and painful, it is better to remain ignorant of the counterevidence and competing theories.

6. Appeal to Authority

Some believers appeal to the authority of Torah sages whose views, for them, have greater weight than the findings and theories of professors in matters of belief. They work with the assumption that Torah sages have actually spent time thinking about these questions seriously. The comments of Rabbi Shlomo Sternberg, Professor of Mathematics at Harvard University, in his article analyzing the history of rabbinic responses to medical and scientific findings that contradict assumptions about medicine and science that are the basis for Talmudic halakha, is illuminating:

A third position taken by many Halakhic authorities is one of denial—to refuse to accept scientific statements (even quite standard ones) if they flatly contradict Talmudic doctrines which have Halakhic implications… As this denial might seem strange… we should pause a moment to understand what is involved. Science as a whole is a belief system, to the extent that it depends on trust, in the sense that no one individual can understand all the arguments from the first principles or reproduce the basic experiments which constitute scientific evidence for even the most fundamental and universally accepted tenets in most fields… The man in the street has no more direct experience with bacteria or quarks or buckyballs than he has with demons or the evil eye or astrology. To choose one system over another is ultimately an act of faith for most people. For someone reared entirely in the Yeshiva world, the Talmud and its commentators represent the ultimate authority. Hence when there is a direct challenge to the veracity of statements of Hazal [rabbinic sages of the Talmudic period], especially when these statements have direct halakhic consequences, it is easy to understand how one may choose to deny the scientist’s claims.” (pp. 86-87).[8]

7. Claiming that our Knowledge is Limited

Some Orthodox believers assert that there are limits to what we can know or infer from reason and empirical evidence. This, of course, is quite true. However, they invoke this argument selectively. They will use what they claim to be evidence and reason to bolster their own beliefs and convince others of them. But when they are presented with compelling evidence and arguments against the belief in Torah-Mi-Sinai they will assert that reason and empirical findings cannot be relied upon to determine the truth or falsehood of their orthodox beliefs.

8. Preemptive Theology

One way of reducing or eliminating dissonance that is generated by facts or arguments that challenge a belief system is to anticipate and neutralize them by what I would call “preemptive theology.” Preemptive theology often originates only after a threat or challenge has been posed, and was thus initially reactive theology. Once, however, the theological response to the challenge is formulated, it then serves to preempt the threat for the next generation of believers who will be exposed to the same or similar threats.

An example of this is the classic response of Orthodox Judaism (and fundamentalist Christianity) about how the world could be 6,000 years old when we have found evidence, like dinosaur bones, that date to millions of years ago. One answer offered to this is, “God put dinosaur bones in the ground to test your faith in Torah.” Another is, “Just as God created Adam looking like an adult, he created the universe looking aged as well.” These answers were originally created to solve problems, but they have become standard fare in Haredi education, such that children are taught to believe that God works in this way before they can think of the question themselves, thus avoiding the moment of dissonance or crisis altogether.

The Case of Ba’alei Teshuvah

In discussing strategies for protecting implausible beliefs, it is useful to consider the case of ba’alei teshuva (newly religious Jews). There is a whole ba’al teshuva industry which relies, among other things, on the aforementioned strategies to convince or encourage Jews who have had a secular education, often an excellent one, but who have not had any Jewish education, to become Orthodox.

The Jewish ba’al teshuva, like a convert to any new faith, has a special motive for warding off threats to his new belief system. The process of “repenting” often entails a considerable amount of tension with parents and friends. Often the ba’al teshuva sacrifices a lifestyle that provided material satisfactions and pleasures as well as personal freedom for a new religious lifestyle that restricts the satisfaction of certain physical impulses, imposes a rigorous behavioral discipline, and limits intellectual curiosity and autonomy.

As a result, when the ba’al teshuva perceives a threat to his or her newly acquired religious worldview and lifestyle, the well-known process of cognitive dissonance resolution comes into play. The sacrifices he or she has made and the pain caused to family and friends need to be justified, and the unconscious cognitive mechanisms enumerated above become particularly useful in deflecting any doubts the ba’al teshuva might experience regarding his or her lifestyle choice.[9]

Conclusion

Although the strategies for protecting unreasonable beliefs seem alien to me now, I know that earlier in my life I myself used one or another of them to protect my belief in Torah Mi-Sinai and in the divine source and sanctity of the mitzvot(commandments). Therefore, I try not to be too condescending towards secularly educated believers in Torah Mi-Sinai since, for several years, I was one of them.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 24, 2014

|

Last Updated

February 9, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Solomon Schimmel is Professor Emeritus of Jewish Education and Psychology at Hebrew College. He received his Ph.D in Psychology from Wayne State University. Schimmel is the author of The Tenacity of Unreasonable Beliefs: Fundamentalism and the Fear of Truth; Wounds Not Healed by Time: The Power of Repentance and Forgiveness; and The Seven Deadly Sins: Jewish, Christian and Classical Reflections on Human Psychology.

Essays on Related Topics: