Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Where in the Transjordan Did Moses Deliver His Opening Address?

Initial-word panel Elleh (these) decorated with penwork and accompanied by a foliate border, at the beginning of Deuteronomy. Bible Ms. Harley 5710, 13th century. British Library.

The Introduction to Deuteronomy

Like most of Deuteronomy (chs. 1-30), Moses’ first discourse (Deut 1:6-4:40) is presented in first person. The discourse begins in 1:6, where Moses reports what God said to the people at Horeb,[1] and is preceded by an introduction (1:1-5) in a third person editorial voice ending with the word לאמר “saying.”[2] The introduction is long and comprised of several elements.

Verses 1 and 5 are similar, both offering an introductory phrase and a geographical location in the Transjordan:

א:א אֵלֶּה הַדְּבָרִים אֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר מֹשֶׁה אֶל כָּל יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּעֵבֶר הַיַּרְדֵּן בַּמִּדְבָּר בָּעֲרָבָה מוֹל סוּף בֵּין פָּארָן וּבֵין תֹּפֶל וְלָבָן וַחֲצֵרֹת וְדִי זָהָב…

Deut 1:1 These are the words that Moses addressed to all Israel in the Transjordan: in the wilderness, in the Arabah opposite Suph, between Paran and Tophel, and Laban, and Hatzerot, and Di-zahab…

א:ה בְּעֵבֶר הַיַּרְדֵּן בְּאֶרֶץ מוֹאָב הוֹאִיל מֹשֶׁה בֵּאֵר אֶת הַתּוֹרָה הַזֹּאת לֵאמֹר.

1:5 In the Transjordan, in the land of Moab, Moses undertook to expound this Teaching, saying:

Literary minded scholars might point to a chiastic (ABBA) structure here, but this is hardly possible, because the geographic notations modifying “in the Transjordan” in these two verses are not parallel. Whereas v. 5a follows up with a simple clarification “in the land of Moab,” v. 1b follows up with a dizzying list of toponyms:

בְּעֵבֶר הַיַּרְדֵּן

בַּמִּדְבָּר

בָּעֲרָבָה

מוֹל סוּף

בֵּין פָּארָן וּבֵין תֹּפֶל

וְלָבָן

וַחֲצֵרֹת

וְדִי זָהָב.

In the Transjordan.

in the Wilderness,

in the Arabah

opposite Suph,

between Paran and Tophel,

and Laban,

and Hatzerot,

and Di-zahab,

In its current context, this list identifies where Moses delivers his discourse,[3] but it lists several places, rather than a single place.

Places Where Israel Sinned

Traditional commentators have long been aware of this problem. The most common approach among rabbinic commentators, including Targum Onkelos, Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, the Fragmentary Targum, and Rashi, is to read the toponyms in v. 1 as a list of places where the Israelites sinned. For example, Targum Onkelos (mid-first millennium C.E.) translates as follows:

| Toponym | Onkelos’ Translation | ||||

|

בְּעֵבֶר הַיַּרְדֵּן בַּמִּדְבָּר |

In the Transjordan in the Wilderness, |

בְּעִבְרָא דְּיַרְדְּנָא, אוֹכַח יָתְהוֹן עַל דְּחָבוּ בְּמַדְבְּרָא,

|

In the Transjordan he rebuked them because of the sins they committed in the wilderness, | ||

- Reading the first two toponyms together, Onkelos introduces the list as Moses rebuking Israel in the Transjordan for their many sins in the Wilderness.

|

בָּעֲרָבָה מוֹל סוּף

|

in the Arabah opposite Suph, |

וְעַל דְּאַרְגִּיזוּ בְּמֵישְׁרָא לָקֳבֵיל יַם סוּף,

|

and they provoked [God] on the plains opposite the Sea of Rushes, |

- Reading the next two toponyms together, Onkelos is likely referring to the Israelites’ complaint in Exod 14:11-12 before the splitting of the sea: “Why did you take us out of Egypt?

|

בֵּין פָּארָן וּבֵין תֹּפֶל וְלָבָן

|

between Paran and Tophel, and Laban |

בְּפָארָן אִתַּפַּלוּ עַל מַנָּא,

|

in Paran, they made light of the manna, |

- The key to this interpretation is the third toponym, Laban, which means white in Hebrew, and which Onkelos identifies with the manna, which was white in color (Exod 16:31). He reads this reference to manna together with the previous term, which he translates as a verb, “to make light of.” These toponyms then refer to the Israelites’ complaint in Num 11:4-6 and 21:5. He understands the first toponym as a reference to the Wilderness of Paran, where this happened (though they were not in Paran at the time according to the text).

|

וַחֲצֵרֹת

|

and Hatzerot |

בַחֲצֵירוֹת אַרְגִּיזוּ עַל בִּשְׂרָא

|

and in Hatzerot they provoked [God] about meat, |

- This is a reference to the same complaint as above (Num 11:4-6), but this time emphasizing how they wanted meat as opposed to their dislike of the manna. (In Num 11:35, the story takes place in Qivrot-hata’avah; Hatzerot is mentioned as the place they went after this story.)

|

וְדִי זָהָב.

|

and Di-zahab |

וְעַל דַּעֲבַדוּ עֵיגַל דִּדְהַב.

|

and [they provoked God] by serving the golden calf. |

- The second word in this toponym means “gold,” thus Onkelos sees it as a reference to the story of the golden calf in Exodus 32. As this sin would have occurred before the complaints about manna and meat in Num 11, the list is not in chronological order.

According to Onkelos, Transjordan (עבר הירדן) is where Moses rebukes the people for all the sins they committed in the wilderness (במדבר). And since places like Tophel, Laban, and Di-zahab are never mentioned in the itinerary lists of Exodus and Numbers, he believes that these names are hints to events, rather than proper place names.

But why would the verse be written this way? Rashi (1040-1105), who also reads the list in an allegorical manner, suggests a reason:

אלה הדברים – לפי שהן דברי תוכחות, ומנה כאן כל המקומות שהכעיסו ישראל את המקום, סתם את הדברים והזכירן ברמז מפני כבודן של ישראל.

“These are the words” – because these will be words of rebuke, and he is listing all the places where the Israelites angered God, [Moses] made his words opaque, and mentioned [the sins] only in hints, out of consideration for Israel’s honor.

This approach to the verse had important consequences in Jewish interpretation, leading to the principle that the opening discourse of Deuteronomy is really a rebuke.

Nevertheless, it goes without saying that this is impossible as a peshat reading of the verse: it uses fanciful translations and ignores prepositions (“opposite,” “between”).

Places Where the Mitzvot Were Taught

Some medieval commentators accepted the basic insight that the list cannot be describing the current place of the encampment, but suggested, against the Targumim and Rashi, that these were the places where Moses taught Torah. This at least fits the opening of the verse, “these are the words that Moses spoke in…” R. Joseph Bekhor Shor (12th cent.) expresses this point clearly:[4]

סמוך למיתתו סידר להם את התורה כדי שלא ישתכחו את המצות. ואומר: כי אלה הדברים שהוא מזכיר להם עכשיו, נאמרו: בעבר הירדן…

Near his death, [Moses] reviewed the Torah for them, so that the commandments not be forgotten. And [the verse] says, these matters that he is reminding them of now, were stated (originally) in the Transjordan…

This interpretation is also problematic. If Moses is reminding the Israelites of when he taught these matters earlier, why does he use so many unfamiliar toponyms?[5]

A second problem is that Bekhor Shor is reading the list as retrospective, i.e., as the places Moses once taught the Israelites the very same matters he is about to teach them again. But the verse does not frame the list in this way, but rather as the place(s) where Moses will deliver a discourse.

Three Places of Revelation

R. David Zvi Hoffmann (1843-1921) builds upon the observation that the first few toponyms begin with “in” (ב), while from the phrase “between Paran and Tophel” on, the toponyms all begin with “and” (ו). Thus, he suggests that all the toponyms following Paran are describing the location of only one encampment.

“בין פארן ובין תופל… ודי זהב”. כל התיאור הזה מ”בין פארן” עד “ודי זהב” אינו יכול להתייחס אלא למקום אחד, כי אלמלא כן היה צורך לכתוב עוד הפעם ב, לפני כל שם (בלבן בחצרות ובדי זהב).

“Between Paran and Tophel… and Di-zahab” – This entire description from “between Paran” till “and Di-zahab” can only refer to one place, since if not, the text would have to add again the preposition “in” before each name (“in Laban,” “in Hatzerot,” “in Di-Zahab”).

אם כן המדובר כאן על מקום הנמצא במדבר, המוקף על ידי המקומות פארן, תופל, לבן, חצרות ודי זהב…. הנני סבור שהכוונה למקום חנייתם של ישראל במדבר פארן (במדבר י”ב:ו’) על יד קדש (שם י”ג:כ”ו) מקום שישבו שם ישראל ימים רבים (דברים א’:מ”ו).[6]

If so, we are speaking here of a place in the wilderness, surrounded by these places: Paran, Tophel, Laban, Hatzerot, and Di-zahab… I believe that the reference here is to the place the Israelites encamped in the wilderness of Paran (Num 12:6) near Kadesh (Num 13:26), the place where the Israelites dwelt for many years (Deut 1:46).

Hoffmann uses this grammatical point to suggest that the verse is actually describing three areas where God revealed laws to Moses:[7]

- “In the Transjordan,” i.e., in the area of Moab;

- “In the Wilderness, [which is] in the Arabah[8] opposite Suph,” this refers to the southern Arabah, between the Dead Sea and the Red Sea;

- “Between Paran and Tophel, Laban, Hatzerot, and Di-zahab” – the area around Kadesh-barnea.

Hoffmann’s approach is problematic as well.[9] First, it is quite unusual to demarcate one area with five toponyms. Second, this reading is only possible because Hoffmann rejects the standard identifications of Laban and Tophel (which will be discussed below), calling them “uncertain,” without suggesting reasonable alternatives. Thus, he frees himself of having to explain the geography; these sites can be anywhere, so he places them near Kadesh-barnea to make his theory work.

Third, if the list is meant to describe the places where God revealed laws to Moses, the absence of Horeb in this list is very surprising.[10] Indeed, the verse is not about revelation: It does not say “these are the places God taught laws to Moses,” but “these are the words Moses taught to Israel in these places.”

Finally, as noted above, the verse is not referring to where the Israelites were before Moses delivered his Deuteronomic discourse, but where they were encamped when Moses delivered his discourse.

“An Incomprehensible Interpolation”

Finding none of these solutions acceptable, critical scholars have long argued that the list of toponyms in v. 1 (other than perhaps “in the Transjordan,” which is repeated in v. 5) are not integral to the verse but are likely a later supplement. But where is this supplement from and why was it added?

Many scholars have thrown up their hands at this question. For example, the Hebrew University Bible scholar, Menahem Haran (1924-2015), simply states that “it is an incomprehensible interpolation whose [meaning and origin] cannot be reconstructed and from which we can learn nothing”[11](הוא שירבוב סתום ללא תקנה ואין ללמוד ממנו). Nevertheless, I believe that we can find the origin of this interpolation.

An Itinerary List

R. Ovadiah Seforno (ca. 1475-1550) suggested that these toponyms are an itinerary list from Israel’s travels after the sin of the spies:

וְהֵם מְקוֹמות אֲשֶׁר עִוְּתוּ שָׁם אָרְחוֹת דְּרָכִים, בִּגְזֵרַת הָאֵל יִתְעַלֶּה לַהֲנִיעָם בַּמִּדְבָּר בַּעֲוֹן הַמְרַגְּלִים.

These are places in which they wandered across various roads, as a consequence of God’s decree to force them to wander in the wilderness as a consequence of the sin of the spies.

I believe that Seforno has properly understood the significance of these place names, though he was obviously not making a claim about redaction. I further believe we can identify all the toponyms on the list.

The Geography Behind the List

In the Transjordan (בְּעֵבֶר הַיַּרְדֵּן) – This phrase is likely original to the (D) verse and not part of the supplement. In context, it functions as an umbrella term, indicating that what comes after is in the Transjordan.[12]

In the Wilderness (בַּמִּדְבָּר) – This cannot refer to the Sinai wilderness, which is not in the Transjordan. Instead, it must refer to the area in the western slope of southern Transjordan near Petra (Kadesh),[13] which the Torah calls the “Zin Wilderness” (מדבר צין; Num 20:1, 27:14, 33:36; Deut 32:51).

In the Arabah (בָּעֲרָבָה) – The Bible refers to the Dead Sea as ים הערבה the Arabah Sea,[14] and the area surrounding the Dead Sea, where thin layers of clay and soft chalk (Hawar) sediments are exposed, as the Arabah. These sediments mark the bottom of an ancient sea and are testimony to the extent of the Dead Sea in prehistoric times. On the south, this extends only to Hazeba (the modern-day term Arabah covers an area from the southern end of the Dead Sea extending much further south all the way to Eilat), in the north this area extends far past Jericho, all the way to the modern-day Adam Bridge, just east of Shechem.[15]

Opposite Suph (מוֹל סוּף) – This is not a reference to the Red Sea’s Gulf of Aqaba, and certainly not a reference to the “Lake of Rushes” (Yam Suph) that the Israelites crossed to escape Egypt (Exod 13:18, 15:22). Rather, it is a reference to the Qāʾ al-Jafr catchment area in the southern Transjordan east of Petra/Kadesh, which can form a large seasonal lake during the rainy season, depending on the amount of rainfall in a given year.[16] As the writer is situated in the Cisjordan and looking east, “opposite Suph” means on the west of the Qāʾ al-Jafr, towards the writer.

Between Paran (בֵּין פָּארָן) – Paran here cannot refer to the wilderness of Paran in the Sinai Peninsula, as this is far away from the Transjordan.[17] Instead, it should be identified with Eyl-Paran in the Transjordan found in Genesis 14, in the battle of the four kings:

בראשית יד:ה וּבְאַרְבַּע עֶשְׂרֵה שָׁנָה בָּא כְדָרְלָעֹמֶר וְהַמְּלָכִים אֲשֶׁר אִתּוֹ וַיַּכּוּ אֶת רְפָאִים בְּעַשְׁתְּרֹת קַרְנַיִם וְאֶת הַזּוּזִים בְּהָם וְאֵת הָאֵימִים בְּשָׁוֵה קִרְיָתָיִם. יד:ו וְאֶת הַחֹרִי בְּהַרְרָם שֵׂעִיר עַד אֵיל פָּארָן אֲשֶׁר עַל הַמִּדְבָּר.

Gen 14:5 In the fourteenth year, Chedorlaomer and the kings who were with him came and defeated the Rephaim at Ashteroth-karnaim, the Zuzim at Ham, the Emim at Shave-kiriataim, 14:6 and the Horites in their hill country of Seir as far as Eyl-paran, which is on the [edge of the] desert.[18]

The historian and church-father Eusebius of Caesarea (ca. 260-340) states that Eyl-paran lies three days east of ʿAila[19](modern-day Aqaba).[20] Three days travel northeast (80 kms) on the Roman road familiar to Eusebius[21] would get one to Ras a-Naqeb, a mountain range that rises sharply above the Hisma plain on its south.[22]

Ras a-Naqeb works well with the account in Genesis, since Eyl-Paran would then be on the edge of Arabian Desert (v. 6), and the four kings would have no choice but to travel back through Petra/Kadesh (as per v. 7) to the battlefield with the five rebel kings, since, until the Roman period, there were no other roads back to the Dead Sea area.[23]

And between Tophel (וּבֵין תֹּפֶל) – Scholars have long suggested identifying Tophel with et-Tafileh on the Kings Highway, south of Wadi al-Hasa, based on similarity of sound.[24]

And Laban (וְלָבָן) – B. Grdseloff suggested identifying Laban of our list with one of the Shasu Lands in the Egyptian Topographical Lists also called Laban.[25] As Laban in Hebrew means white, which is translated in Arabic to Abyad, I have suggested identifying it with Rujm Abyad east/north-east of Tafileh.[26]

And Hatzerot (וַחֲצֵרֹת) – Numbers 11:35 mentions a Hazerot in the Sinai Peninsula but this does not fit a Transjordanian context. The Hebrew term חצר, meaning “courtyard” or “fort” is a relatively common element in place names, and was probably used to name permanent shepherds’ encampment.[27] The Bible has a number of חצר names for towns or villages[28] as does the list of conquered places in the Negev in Shishak’s inscription (10th cent.).

We do not know of a Hatzerot in the Transjordan outside of this verse. Nevertheless, an archaeological survey of the Land of Moab identified two settlement areas that are completely different from each other.[29] On Moab’s western side is the Karak Heights, a fertile area where one can find rain-irrigated agriculture.[30] On its eastern side is a grazing area or steppe dotted with small shepherds’ settlements.[31] I suggest identifying this area with Hazerot, a name that evokes the image of multiple shepherd encampments. (In Numbers 21:15 and Deuteronomy 2:9, 18, 29, this area is referred to as Ar.)

And Di-zahab (וְדִי זָהָב) – Zahab means gold in Hebrew. A little over two miles north of Diban/Dibon (UTM 763492) lies the plain of aḏ-Ḏuhaybah. The name is a feminine diminution form of Arabic Dahab, meaning gold (like the name Goldie). Already in 1907, Alois Musil suggested identifying aḏ-Ḏuhaybah with Di-zahab of our verse.[32]

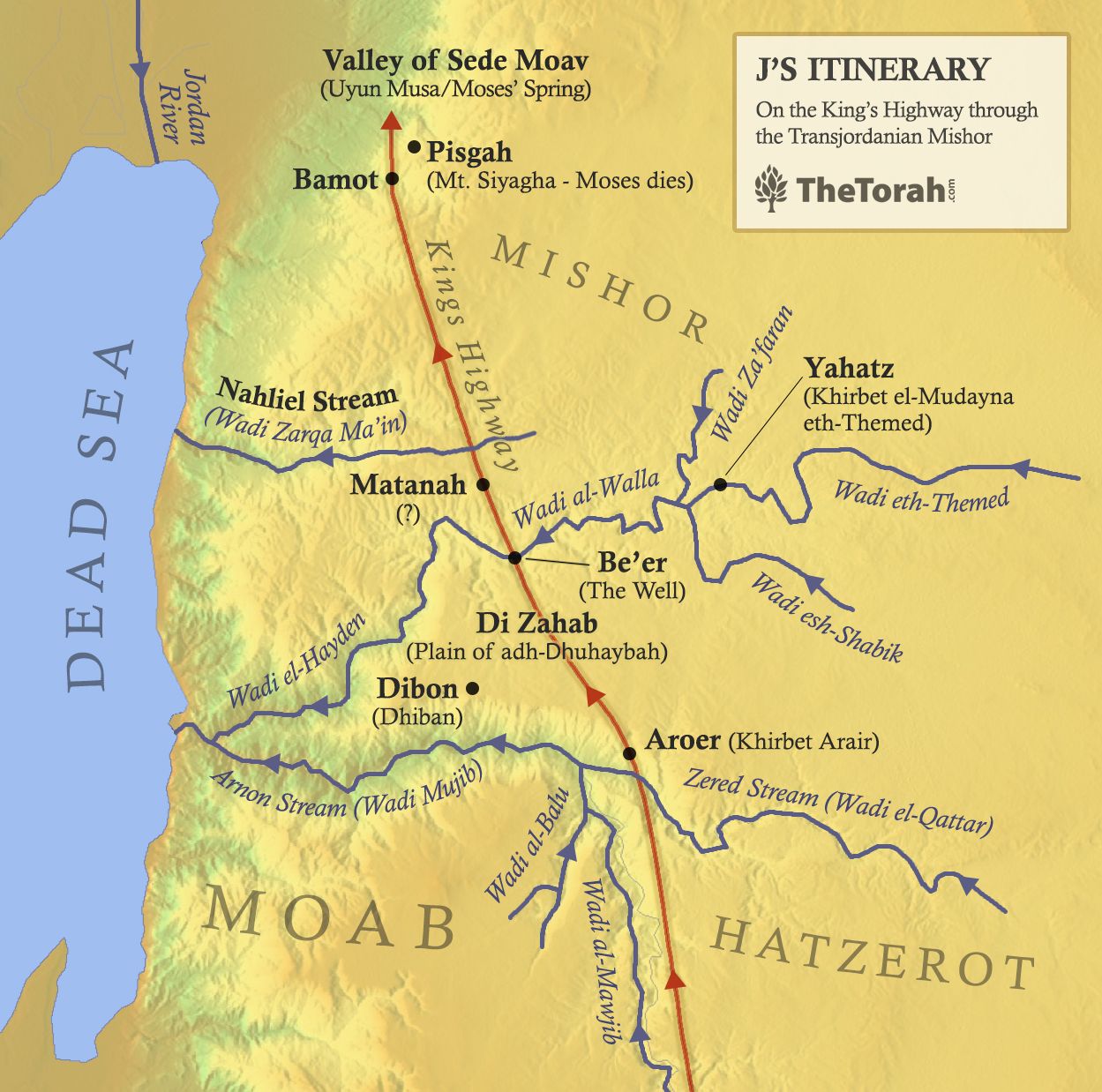

The Journey

Plotting the various toponyms on a map, we get a clear south-north axis, consistent with what we would expect from an itinerary list. The list begins with the Zin Wilderness (the equivalent of modern day Arabah valley plus the lower part of the western slope of the Jordanian hills), followed by the biblical Arabah on the south side of the Dead Sea.

From there, we turn east, climbing the Jordanian Heights south of Wadi al-Hassa. On the heights, the Israelites spread out to occupy the area “opposite Suph, between Paran and Tophel,” namely, the fertile, western part of the Transjordanian Heights south of Wadi al-Hasa,[33] i.e., Edom.

From there, we turn north-east, crossing Wadi al-Hasa towards the steppe east of the Moabite territory. Laban is on the edge of the steppe north-east of Wadi al-Hasa, and Hatzerot is further north just south of the Arnon Stream. (In Deuteronomy 2:18, this area is referred to as Ar.)

Finally, we continue north-west, hitting the ancient crossing for the Arnon Stream at Aroer and end up in Di-zahab, just south of Wadi al-Walla in the southern Mishor. At this point we are on the “Kings Way”, the road that goes north on the west side of the Mishor.

A Missing Piece from J’s Itinerary

The itinerary list here is a stub, since it begins just below Edom and ends up just north of Moab. It connects extraordinarily well with J, since the fragment of the J itinerary that was included in Numbers 21 (vv. 19–20) starts north of the Arnon, exactly where the itinerary of Deut 1:1 leaves off:

Be’er (בְּאֵר) – Be’er means “the well,” and the story in Numbers 21 indicates that the place is named after an actual well. It is difficult to locate a well after millennia (there are many ancient wells), but the best place to dig for water north of Di-zahab is Wadi al-Walla. As the Israelites will be moving northwest from Di-zahab till they arrive at Pisgah, somewhere in the vicinity of Wadi al-Walla north/northwest of Di-zahab is where we should look for Be’er. Moreover, as Di-zahab and Pisgah are both on what is called “the Kings Highway,” the area of Beer should be as well.

Mattanah (מַתָּנָה) – This toponym is unknown, other than it is northwest of Di-zahab, and likely before the next stream on the Jordanian Heights and on the Kings Highway.

Nahliel (נַחֲלִיאֵל) – If this toponym is the name of a stream (Hebrew – Nahal נחל), and as the Israelites had to stay on the Jordanian Heights to get to Bamoth and Pisgah, the best candidate is Wadi Zarqa Ma’in which flows from the Heights into the Dead Sea.

Bamot (בָּמוֹת) – Many scholars identify Bamot with Bamot-Baal of Balaam (Num 22:41), a Reubenite city in the plain of Heshbon (Josh 13:17).[34] As from Bamot-baal, one could overlook the Israelite camp, and as it is mentioned before Pisgah it was probably on the west side of the plain, a little south of the peak of Pisgah.

“The valley that is in the fields of Moab, at the peak of Pisgah, overlooking the wasteland” (הַגַּיְא אֲשֶׁר בִּשְׂדֵה מוֹאָב רֹאשׁ הַפִּסְגָּה וְנִשְׁקָפָה עַל פְּנֵי הַיְשִׁימֹן) – This is the final stop on the itinerary and it anchors the rest. This is J’s term for what is called in another biblical source, the “Peak of Peor” (Num 23:28) since the mountain also overlooks the valley of Peor.[35]The valley is next to Beth-Peor, which is identified with the area near the Uyun-Musa (Arabic for Moses’ Spring).[36] The mountain overlooking this valley refers to Mount Siyagha (also called Mount Nebo), or a neighboring peak.

A Peaceful Trek

Another connection between these two itinerary fragments is thematic, since each describes the Israelites’ trek through the Transjordan as occurring without incident. According to J, Israel occupies the main territory of Edom. This directly contradicts the E account (Num 20:14–21), which has the Israelites attempt to enter Edom at Kadesh only to be stopped by the Edomite king and his army (Num 20:18–20).[37]

Moreover, Israel’s peaceful journey through the Transjordanian Mishor in J contrasts sharply with the E account, according to which Sihon, King of the Amorites, attacks them, the two groups fight a battle in the area of Yahatz, and Israel ends up conquering the territory (Num 21:21-25).[38] P, like E, has an account of a battle, in Jazer (Num 21:32) after which the Israelites occupy the Mishor – the Land of the Amorites. J’s version of the settlement of the Transjordan area north of Arnon is again uneventful:

במדבר כא:לא וַיֵּשֶׁב יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּאֶרֶץ הָאֱמֹרִי.

Num 21:31 And Israel settled in the land of the Amorites.

In short, J does not deal with the problem of native inhabitants through which the people must move. The Israelites simply travel unhindered through the middle of these territories until they arrive at Pisgah, where Moses dies, and even settle the area without conflict.

Why Was It Cut?

When putting together Numbers 21, the compiler used the E itinerary as his base, to get the Israelites to Yahatz and the battle with Sihon. To make the way from Kadesh to Yahatz as simple as possible, the redactor omitted from both E and P the part of the itinerary that goes through the Arabah, keeping only the incident of the copper serpent of E.

As J takes the Israelites to Di-zahab, away from Yahatz, the southern part of J’s itinerary, until the Israelites arrive in the northern Mishor (north of Wadi al-Walla), was omitted from Number 21.[39] Nevertheless, out of reverence for ancient documents, R (the compiler) included it in Deuteronomy to avoid losing the list entirely.[40]

Thus, R used the reference to when the Israelites were in the Transjordan (v. 1a) to insert this stub that dealt with Israel’s Transjordanian journey. R tried to make this itinerary fit the context better by changing it from a travelogue to a simple list of places in the Transjordan. Nevertheless, it is clear from v. 5 that originally, the words “in the Transjordan” were coterminous with “in the land of Moab,” i.e., Moab after the Mesha’s conquest in the 9th century, whose borders included the Mishor and the Jordan valley, north-east of the Dead Sea.[41]

Hypothetical Reconstruction of J’s Transjordanian Itinerary

To take the speculative source analysis one step further, if we retrovert the list in Deut 1:1 to the J itinerary style in Number 21:16-20, and put the two lists together, we get the following:

ממדבר ערבה ומערבה[42] מוֹל סוּף בין פארן ובין-תֹפל. משם לבן וּמלבן חצרֹת וּמחצרֹת די זהב וּמדי זָהָב בארה.

From the Wilderness to the Arabah, and from the Arabah, to opposite Suph, between Paran and Tophel. From there to Laban, and from Laban to Hatzerot, and from Hatzerot to Di-zahab, and from Di-zahab to the well.

אז ישיר ישראל את השִירה הזֹּאת עלי באר ענוּ לה. באר חפרוּה שרים כרוּה נדיבי העם במחֹקק במשענֹתם.

Then the Israelites said this song: “Spring up, O well — sing to it — The well which the chieftains dug, Which the nobles of the people started with maces, with their own staffs.

ומ[באר][43]מתנה וּממתנה נחליאל וּמנחליאל במוֹת וּמבמוֹת הגיא אשר בשדה מוֹאב רֹאש הפסגה ונשקפה על פני הישימֹן.

And from [the well] Mattanah, and from Mattanah, Nahliel, and from Nahliel, Bamot, and from Bamot the valley that is in the fields of Moab, at the peak of Pisgah, overlooking the wasteland.

The Real Secret of the List in Deut 1:1

Thus, the itinerary list in Deuteronomy 1:1 does hide a secret, but it isn’t a rebuke of Israel for their sins. Instead the secret is that, according to at least one source, Israel’s trip through the Transjordan was entirely uneventful. They travelled directly through the lands of Edom without incident, even settling there for a time, and entered the Transjordanian Mishor, which would become part of Israel’s territory, without fighting even a single battle.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 19, 2018

|

Last Updated

January 27, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. David Ben-Gad HaCohen (Dudu Cohen) has a Ph.D. in Hebrew Bible from the Hebrew University. His dissertation is titled, Kadesh in the Pentateuchal Narratives, and deals with issues of biblical criticism and historical geography. Dudu has been a licensed Israeli guide since 1972. He conducts tours in Israel as well as Jordan.

Essays on Related Topics: