Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Biblical Exegesis as a Source of Jewish Pluralism: The Case of the Karaites

Categories:

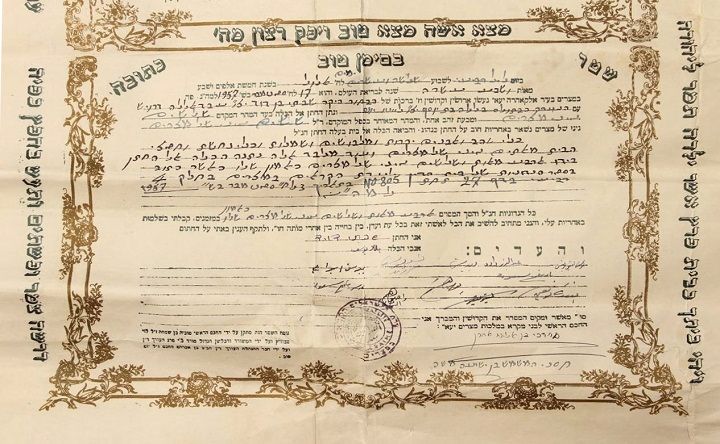

Reading from the new Torah during Jubilee celebrations for the Anan HaNasi Synagogue, Ashdod, Israel. June 2013. Facebook היהדות הקראית העולמית-The Universal Karaite Judaism

A Brief History of Karaism

It is often thought that Anan ben David, an eighth-century unsuccessful candidate to be the Babylonian exilarch, namely the political head of the Jewish community in present-day Iraq, was the founder of Karaism. Current research, however, understands that the process by which Karaism emerged is more complex than its being merely a schismatic movement invented by a disgruntled office seeker.

In the early Islamic period, namely the seventh to ninth centuries, there were a number of non-Rabbinic Jewish groups which did not accept the authority of the Talmud. Whether the practices and beliefs of these groups had ancient roots, perhaps as far back as the Second Temple, or were innovations by their founders in the context of Islamic sectarianism, is difficult to determine. These groups, including Anan’s movement, Ananism, eventually coalesced into what is now known as Karaism, which seems to have emerged in the mid-ninth century. Anan was later retroactively given a prominent role by the Karaites in the history of their community.[1]

The Importance of Searching Scripture – “Anan’s Credo”

Karaites are often considered strict scripturalists, among other reasons because of Anan’s putative credo: חפישו באורייתא שפיר ואל תשענו על דעתי (hapisu be-oraita shapir ve-‘ al tishcanu cal dacati; “search Scriptures well and do not rely on my opinion”). Doubts have been raised concerning the attribution of this sentiment to Anan since he was neither a literalist, nor did he appear to be a pluralist in religious behavior. Despite these caveats, “Anan’s credo” partially reflects the Karaite attitude toward the Bible, namely the importance of close examination of the Bible alone to determine how to observe the divine commandments.[2]

Relationship between Karaites and Rabbanites[3]

Although the Rabbanite and Karaite forms of Judaism are distinct, the differences did not lead to a radical break between the two groups, and Karaites throughout history were part of the Jewish body politic, even if they observed an alternate form of Jewish law. In the Islamic east, namely the Land of Israel, Egypt, and Iraq, Karaites were considered simply followers of a different type of Judaism, making Rabbanism and Karaism similar to the variant legal schools of Islam (madhahib). The two groups vied for political and economic clout, but relations between them were sufficiently close that Karaites and Rabbanites lived in proximity.

Karaites and Rabbanites even married each other, usually after some sort of pre-nuptial agreement was reached concerning the religious character of the household, especially in the formative period of Karaism (9th-11th centuries). In Islamic countries, most notably in Egypt, this pattern continued through the centuries, and legal difficulties confronting these marriages were solved. Ashkenazic Rabbanite Jews, depending upon a ruling attributed to Rabbi Samson of Sens (1150-1230), as codified by Rabbi Moses Isserles (1520-1572), have generally ruled that it is forbidden to marry Karaites, making rapprochement between these two groups more difficult.[4]

The Center of Karaite Life

After its very productive formative period in the Land of Israel (9th-11th centuries, the “Golden Age” of Karaism), the center of Karaite life moved to the Byzantine Empire and flourished there between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries. It was during this period that Karaites moved closer and closer to Rabbanite beliefs and practices, although they maintained their separate identities.

In the early modern period, Karaites established communities in Crimea and in eastern European cities such as Troki in Lithuania, Halicz in Galicia and Lutsk in Volhynia. Relations between Karaites and Rabbanites grew further apart, among other reasons because they spoke different languages;[5]nevertheless, taxes from Karaites to the central governments were paid through the Rabbanite Council of Four Lands.

Only in the nineteenth century did Karaites begin to establish a separate identity to avoid the disabilities under which Jews suffered in the Russian Empire, and in the twentieth century they denied any affinity with Jews. These Eastern European Karaites asserted that they were descendants of Central Asian tribes, a claim which stood them in good stead during the Holocaust since the Nazis generally decided that they were not racially Jewish. Karaism has survived to this day, and most contemporary Karaites are of Egyptian origin and live in Israel, and identify as part of the Jewish people.[6]

Karaite Separatism

How does a group of Jews become a separate, identifiable Jewish entity? Many components define Jewish identity, and variations in one or more of these may lead to schism or separation.

1. Theology – An investigation of Karaite theology indicates that classical Karaism was extremely close to classical Rabbanism. If one takes Maimonides’ thirteen principles as a benchmark of Rabbanite orthodoxy, it is clear that Karaites can uphold 12 ½ of these principles (not accepting half of principle 8, the authority of the Oral Torah). In fact, most Karaite lists of principles read very much like Rabbanite ones, including the existence, unity and incorporeality of God; the truth of prophecy and the superiority of the prophecy of Moses; and reward and punishment in one form or another.[7]

2. Socio-economic status – One is hard pressed as well to find socio-economic differences between Karaites and Rabbanites. Although one theory of Karaite origins posits that the lower classes (those who turned towards Karaism) revolted against the social and economic hegemony of the Rabbis, there is little basis for this supposition. In fact, in the early period of Karaism, many of the Karaites were among the financial, social, and intellectual elite.

3. Ethnic origin – Karaites and Rabbanites shared the same ethnic origins (despite the recent claims of Eastern European Karaites). Moreover, throughout Jewish history, the Rabbanite and Karaite communities which lived side by side generally considered each other as part of the same larger collective.

4. Way of life (halacha) – This is the determinative factor: The extent to which Karaites existed as a separate, distinct Jewish group was governed by differences in practice between them and the majority Rabbanites. Karaite tradition is different from the Rabbanite Oral Torah, since the Karaites do not consider their interpretations to be Sinaitic. Rather, they claim that these interpretations fit with and do not contradict the Written Torah as the Rabbanite Oral Torah does, from their perspective.

Halacha and Exegesis

Many of the differences between Karaite and Rabbanite law are a function of divergent biblical exegesis. In recent years, especially in light of increased accessibility of Karaite texts, more and more attention has been devoted to Karaite exegetical methods, concerning both biblical narrative and law.

Although Biblical exegesis is important for Karaites, they are not literalists. Karaites are well aware that it is impossible to follow every precept in the Torah literally, since there are many details left out of the biblical text. Indeed, they have their own concept of tradition, describing it with such terms as סבל הירושה (sevel ha-yerushah, “the burden of inheritance”) or העתקה (hacataqah, “transmission”). In fact, as we shall see, sometimes Rabbanites follow a literal reading of certain passages in the Torah, whereas the Karaites take the same verses allegorically, insisting that that is the Torah’s intention.

Either way, the differences in how halachic passages were interpreted became the key dividing line between the communities. As examples, we will look at Karaite/Rabbanite variations in dietary laws, calendar, prayer, tefillin and mezuzot, and personal status.[8]

Dietary Laws

Rabbanite and Karaite Jews do not eat meat from impure animals (temei’ot, namely pigs, camels, rabbits); or from animals which have died on their own (neveilot); or from animals which were not killed by ritual slaughter (tereifot). They both slaughter animals by cutting the neck, even though this is never commanded directly in the Torah, but their blessings differ; Karaites praise God for allowing slaughter, not for commanding it, since no one is obligated to eat meat.

Rabbanite blessing:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֹתָיו וְצִוָּנוּ עַל הַשְּׁחִיטָה

Blessed are you, Lord our God, king of the universe, who sanctified us with His commandments, and commanded us regarding [proper] slaughtering.

Karaite blessing:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֹתָיו וְהִתִּיר לָנוּ לִשְׁחוֺט בְּהֵמָה טְהוֺרָה

Blessed are you, Lord our God, king of the universe, who sanctified us with His commandments, and permitted us to slaughter pure (ṭahor) animals.

The Karaite blessing actually includes three variant endings depending on what kind of animal is slaughtered: בהמה טהורה for domesticated animals (goats, sheep, or cows), חיה טהורה for wild animals (such as ibex or deer), and עוף טהור for fowl.

Karaite and Rabbanite Jews differ in methods of checking the slaughtered animal for disease, and the Karaites have a divergent understanding of the prohibition of the sciatic nerve and forbidden fats.[9]

No Prohibition of Meat and Milk

All these differences pale, however, before the central mark of Karaite dietary distinction, namely their lack of a blanket prohibition of eating, cooking, and benefiting from mixtures of milk and meat. Their kitchens are not characterized by separate utensils for milk and meat and they do not wait between eating meat and dairy products, eating them together unless the meat and milk come from the same species.

The Rabbinic prohibition of milk and meat together is based upon three biblical passages (Exod. 23:19; 34:26; Deut. 14:21) each of which concludes with the statement: Do not cook a goat in its mother’s milk (לא תבשל גדי בחלב אמו). Anan ben David understood the verse to mean: do not let the first fruits (gedi—not goat, but produce, as in meged) to ripen (tevasheil has the same meaning of le-havshil, to ripen) in the field on the tree (the milk of its mother); rather, one must bring the first fruits quickly to Temple.[10]

Karaites (as opposed to Ananites) did not accept this interpretation of the prohibition found in Exodus and Deuteronomy. Thus, Yaqob al-Qirqisani, Rav Saadia Gaon’s contemporary in early tenth-century Iraq, dismisses Anan’s interpretation as allegoristic.[11]

Rather Qirqisani, and Karaites in general, understand the prohibition of “cooking a goat in its mother’s milk” as meaning exactly what it says. Even so, by use of exegetical tools, Karaite scholars have expanded the law to prohibit cooking a mother goat in its daughter’s milk, or eating milk and meat of the same species at the same meal (lamb and cow’s milk, for instance, would be allowed, as would eating chicken with any milk, an act originally permitted in parts of the Rabbinic tradition as well).[12]

In short, different dietary regulations are one of the basic signs of separate religious identity, and Karaite dietary laws are very different than Rabbanite ones, mainly because of a different biblical exegesis.

Calendar

Historically, the utilization of divergent calendars is a good sign of schism, and this is the case for the Rabbanites and Karaites as well.[13] The laws in the Torah (such as holidays on certain days of certain months) assume the existence of a calendar, but there is almost no guidance in the Bible as to how the calendar is to be formulated. For example, Exod. 12:2 proclaims that the month of the going out of Egypt is the first month of the year,[14] and, indeed, the date of Passover is the fourteenth day of the first month. But, are the years and the months, only a few of which have names in the Bible, solar or lunar? How is the calendar to be determined?[15]

The Rabbinic Luni-Solar Calendar Based on Observation

Scholars are divided as to how the biblical calendar was originally constructed, and it is clear that competing calendrical systems existed in the Second Temple period.[16]Ultimately, the calendar which became accepted by Rabbinic Judaism was a luni-solar one, combining lunar months while guaranteeing that the holidays were celebrated each year in the same solar seasons by periodically intercalating a leap month.

Rabbinic literature describes the situation in which the lunar months were determined by the testimony of witnesses who had seen the new moon and leap years were set both by observation of agricultural conditions and by the calculation of the vernal equinox. This system, portrayed in the Mishnah, which was practiced by the central Jerusalem court in the Second Temple, continued even after the destruction, when the central court was located in different places in the Land of Israel.

A Fixed Calculated Calendar

A calendar based on actual astronomical observation is extremely unwieldy when the people who are meant to follow this calendar are widely distributed and means of communication are limited (which is why Rabbanite Jews in the Diaspora adopted a second day of the holidays to make sure they were observing the correct day, a practice maintained today even though there are no doubts concerning the calendar). Thus, by the time of the emergence of Karaism in the ninth century, the Rabbanite calendar was no longer dependent upon eye witnesses or natural phenomena, but rather upon mathematical calculation which only partially reflected the natural phenomena.

When the last internal Rabbanite calendrical controversy was conducted in the tenth century between Rav Saadia Gaon of Babylonia and Rav Aaron Ben-Meir, the Gaon of the Land of Israel, the argument was over how the calendar was to be calculated, not if it should to be calculated altogether. After that controversy, the calculated calendar as we have it today seems to have been accepted by all Rabbanites with virtually no further disagreement, and some authorities even considered it to be the more authentic method of calendation, going back to Moses at Sinai. It was no longer necessary to observe the new moon every month to know the day of Rosh Chodesh, or to look for the signs of spring in order to decide whether a year was to be intercalated by adding an additional month.

Karaite Calendar

Karaites, however, did not accept Rabbanite accommodation to dispersion and the absence of a central authority for setting the calendar. They argued that the correct way of determining the calendar continued to be according to actual observation of natural phenomenon, and not by use of mathematical calculation. Although the Karaites themselves acknowledge that there is no specific verse concerning the making of the calendar, they rely upon Gen. 1:14 as an indication that one actually has to see the movements of the moon and the sun to determine the calendar:[17]

וְהָיוּ לְאֹתֹת וּלְמוֹעֲדִים וּלְיָמִים וְשָׁנִים:

And let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years.

Furthermore, the commandment that Passover be in the month of “Aviv” (Deut. 16:1), interpreted by Rabbanites to mean that the holiday must come in the spring season, is understood by the Karaites as an injunction that the holiday fall during the month of the ripening barley. Hence, for Karaites, a leap year would be declared only if the barley had not ripened by the end of Adar, something which could be checked only by actual observation.

Thus, even though the two calendars had the same basic structure, the Karaite months were often different from the Rabbanite ones by a day or two; and some Rabbanite leap years were regular years in the Karaite calendar and vice versa. Even after the Karaites were forced by the exigencies of diasporic life to use a calculated calendar, and they began to follow the Rabbanite method of intercalating years, minor discrepancies remained between the two systems.[18]

No Pushing Off Holidays

The most significant difference between the two calendars was the method of determining when the holidays would fall. Lev. 23:4 reads:

אֵלֶּה מוֹעֲדֵי יְ-הוָה מִקְרָאֵי קֹדֶשׁ אֲשֶׁר תִּקְרְאוּ אֹתָם בְּמוֹעֲדָם.

These are the appointed feasts of the LORD, the holy convocations, which you shall proclaim (them) in their appointed season.

The Rabbis noticed that the word otam, “them,” referring to the holidays, could as easily be vocalized atem, “you,” understanding that the human element, the beit din, the Rabbinic court, was paramount in determining when the holidays would occur. That included the possibility of making sure the holidays did not fall on undesired days of the week, which was accomplished by the dehiyyot, “the postponements.” The most famous postponement ensures that the first day of Rosh Hashanah cannot fall on a Sunday, a Wednesday, or a Friday [19] (לא אד”ו ראש);other postponements are generally functions of that postponement.

Karaites, however, emphasize the part of the verse that reads, “in their appointed season.” If, for instance, Tishrei’s new moon indicates that Rosh Hashanah (generally called in Karaite sources, yom terucah)[20] should fall on a Friday, then so be it, despite the hardship caused by a Sunday Yom Kippur coming immediately following the Sabbath. Thus, the Karaite calendar has no dehiyyot, and each of the holidays can fall on any day of the week.

Shavuot

One major exception to the above generalization that holidays in the Karaite calendar can fall out on any day of the week is the holiday of Shavuot which, in the Karaite calendar, can fall only on a Sunday. In a manner reminiscent of some Second Temple Jewish groups, Karaites interpret Lev. 23:15, mi-mahorat ha-shabbat (“on the morrow of the Sabbath”) to mean that the omer (sheaf) offering always begins on a Saturday night, and Shavuot occurs fifty days later on Saturday night/Sunday (on different dates in Sivan). In the Rabbanite exegesis, the morrow of the Sabbath is the night after the first day of Passover, and Shavuot always occurs on the sixth of Sivan.

Prayer

How Many Times a Day?

The Bible provides no guidelines for ritual prayer, and later Rabbinic figures were divided as to whether there is a commandment in the Torah to pray.

Rabbanite Jews pray three times a day. This is based on several texts, including the apparent references to three prayer times in biblical verses,

Dan 6:11

וְזִמְנִין תְּלָתָה בְיוֹמָא הוּא בָּרֵךְ עַל בִּרְכוֹהִי וּמְצַלֵּא וּמוֹדֵא קֳדָם אֱלָהֵהּ.

He got down upon his knees three times a day and prayed and gave thanks before his God.

Ps 55:18

עֶרֶב וָבֹקֶר וְצָהֳרַיִם אָשִׂיחָה וְאֶהֱמֶה וַיִּשְׁמַע קוֹלִי.

Evening and morning and at noon I utter my complaint and moan, and he will hear my voice.

Karaites, however, rely on a different verse to determine the number of daily prayers:

1 Chron. 23:30

וְלַעֲמֹד בַּבֹּקֶר בַּבֹּקֶר לְהֹדוֹת וּלְהַלֵּל לַי-הוָה וְכֵן לָעָרֶב.

And they shall stand every morning, thanking and praising the Lord, and likewise at evening.

This verse is used as the basis of the number of daily prayers because it was understood in conjunction with the two daily sacrifices (Num. 28:4); hence, Karaites prescribe prayer only twice a day.

Form of Prayer

The structure of Rabbanite prayer is post-biblical; the Bible itself never even hints at the structure of the central Rabbinic prayer, the Shemoneh cEsreh (the “Eighteen Benedictions”). Eschewing non-biblical modes of devotion, originally Karaite prayer consisted merely of biblical verses, mostly from the Psalms, which they consider to have been revealed by King David as the prayer book of the Jewish people.[21]

Eventually, Karaites added additional compositions and benedictions, some even borrowed from the Rabbanite prayer book.[22] Nevertheless, the structure and contents of the liturgies of the two groups are completely different, another sign of religious separation.

Posture

Karaite posture in prayer differs from its Rabbanite counterpart as well. Basing themselves on the injunctions to Moses (Exod. 3:5) and Joshua (5:15), they remove their shoes before entering the synagogue. Karaite prayer is characterized by full prostration, based on different verses in the Bible that describe bowing as part of prayer, e.g., Ps. 95:6:

בֹּאוּ נִשְׁתַּחֲוֶה וְנִכְרָעָה נִבְרְכָה לִפְנֵי יְ-הוָה עֹשֵׂנוּ.

Let us worship and bow down, let us kneel before the Lord, our Maker.

In fact, the fifteenth-century Elijah Bashyatchi identifies eleven bodily modes which accompany prayer, including various forms of bowing and prostration, as well as lifting one’s hands and raising and lowering one’s voice. Karaite synagogues do not have chairs; when not standing or genuflecting, Karaite worshippers sit on the floor.[23]

Tzitzit, Tefillin, and Mezuzah

Karaites and Rabbanites wear tzitzit, based on Num 15:38, albeit with the strings and knots arranged in different manners.[24] Moreover, both Karaites and Rabbanites place their tzitzit on a tallit (prayer shawl) and wear them during prayer.

Karaites, however, do not wear tefillin (phylacteries). Rabbanites use tefillin as a result of an extremely literal interpretation of an injunction repeated four times in the Torah for Israelites to place “a sign” upon their arms and a “memorial” or a “totafot” (meaning unknown) between their eyes (Exod 13:9, 16; Deut 6:8, 11:18).[25] Karaites, however, say the verses should be taken figuratively: just as the hand has ten fingers, one is to remember the Ten Commandments, keeping them constantly in mind (“memorial between your eyes”).

In a similar manner, Karaites eschew the Rabbanite mezuzah on the doorposts, interpreting Deut. 6:9 and 11:20: “You shall write them on the doorposts of your houses and your gates,” (וּכְתַבְתָּם עַל מְזוּזוֹת בֵּיתֶךָ וּבִשְׁעָרֶיךָ) to mean that these words should be before you always when you come and go. They do, however, put a small reminder of the Ten Commandments in the place where Rabbanites place the mezuzah with its biblical passages. It is instructive to compare how the “literalist” Karaites differ in these commandments from the “non-literalist” Rabbanites.

Personal status (Marriage and Divorce)

Rabbanite and Karaite halakha differs on a number of issues concerning personal status, including:

- Which sexual relations are considered incestuous?

- How do couples marry and divorce?

- What is the status of levirate marriage?

Since the product of an adulterous or incestuous relation is considered a mamzer (someone who cannot marry Jews who have no taint in their heritage), these divergences are significant and lead to the possibility that one side will consider the other one as not marriageable. Intermarriage between Karaites and Rabbanites would, thus, be forbidden.

1. Incestuous Relationship.

The Torah’s lists of forbidden relations (Lev. 18, 20) seem sufficiently explicit and comprehensive so that Rabbanites and Karaites could agree on them, but this is not the case, since the question arises as to whether one can use exegetical or logical tools to expand the prohibitions.[26] For instance, Karaites, like other non-Rabbinic Jewish groups, such as the Sadducees and the Dead Sea Covenanters, employed logical analogy to extend the Torah’s prohibition of aunt-nephew marriage (Lev. 18:12; 20:19) to apply to uncle-niece marriage as well, a relationship allowed in Rabbinic halakha.

In addition, for a number of centuries, early Karaites followed the “catenary” theory of incestuous relations (called ריכוב in Hebrew, literally “combination” or “joining”) which posits, on the basis of verses such as Gen. 2:24 (והיו לבשר אחד, “They shall be one flesh”) that each spouse’s relatives become the relatives of the other spouse. The import of this interpretation is that once a couple marries both the husband’s and the wife’s relatives would now be considered first degree relatives to each other. This rule greatly restricted the reservoir of permitted marriage partners, becoming so impractical and untenable that by the eleventh century, the Karaites reformed their practice, still maintaining, however, more restrictive laws of incest than Rabbanites.

2. Marriage and Divorce

The Bible offers little in the way of specific procedures of marriage and divorce.[27] Nevertheless, both Karaites and Rabbanites developed similar though distinct marriage and divorce laws, specifically, in regards to the form of the geṭ (writ of divorce). Moreover, Karaite courts will issue the writ themselves, even without the husband’s permission, when necessary, something Rabbanite courts do not do. (Thus, Karaites do not have an aguna problem.)

For these and other reasons, many Rabbanites do not recognize Karaite divorce, even if they do recognize Karaite marriage, leading to a situation in which Rabbanites could consider adulterous the second marriage of a woman who was married in a Karaite ceremony and was divorced by a Karaite court. Rabbi David Ibn Abi Zimra (Radbaz, sixteenth century Egypt), however, ruled that Karaite marriages are not valid in the first place, and, therefore, remarriage does not constitute adultery. As such, there is no stigma attached to children of such remarried Karaite women and Rabbanite Jews are not forbidden from marrying them. This approach is generally followed in Israel today by Sephardi rabbis.[28]

3. Levirate Marriage

Deut. 25:5-10 obligates the brother of a deceased, childless husband to marry his sister-in-law (or to release her from this relationship by means of halitzah). This obligation, however, is in conflict with the prohibition of a man’s having relations with his brother’s wife, found in Lev. 18:16; 20:21.[29] Rabbanites argue that “brother” should be taken literally, and that the mitzvah of levirate marriage supersedes the prohibition of “wife’s sister” incest in this case. Karaites reject such an interpretation and say that the “brother” to whom reference is made is a distant relative, as in the case of Ruth and Boaz.

Conclusion: United and Divided by the Torah

Rabbanite and Karaite differences extend beyond the few examples discussed in this essay and include almost all features of practical halakha (such as Sabbath and holiday observances and prohibitions, or laws of ritual purity and impurity). Karaites and Rabbanites share common Jewish ancestry. Their respective beliefs and practice are similar enough for both to qualify as forms of the same religion, Judaism, yet they are distinct alternate forms of the religion

As shown above, Rabbanite and Karaite differences are mainly the result of divergent methods of interpreting the Bible. Each community has its own exegesis; each community has its own halakha. The Bible is the central Jewish book, and it often serves as a source of Jewish unity. In the case of Karaism and Rabbanism, the Bible has also become the basis of separation and sectarianism, resulting in one of the many forms of Jewish pluralism.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

June 6, 2017

|

Last Updated

February 7, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Daniel J. Lasker is the Norbert Blechner Professor of Jewish Values in the Goldstein-Goren Department of Jewish Thought at Ben-Gurion University. He holds a Ph.D., M.A. and B.A. from Brandeis University, and also studied at Hebrew University. Among Lasker’s over two hundred publications are From Judah Hadassi to Elijah Bashyatchi: Studies in Late Medieval Karaite Philosophy and The Sage Simhah Isaac Lutski. An Eighteenth-Century Karaite Rabbi. Selected Writings (Hebrew).

Essays on Related Topics: