Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Jehoiachin’s Exile and the Division of Judah

Jehoiachin king of Judah bows in thanks to the Babylonian king Evil-merodach son of Nebuchadrezzar, for giving him amnesty(colorized). Print by Jan Luyken 1700. Rijksmuseum.nl

The First Exile

A little over eleven and a half years before the destruction of the First Temple in 586 B.C.E., an eighteen year old lad named Jehoiachin ascended the throne of Judah precisely as the Babylonian army was marching toward Jerusalem to lay a siege on the city.

מלכים ב כד:ח בֶּן שְׁמֹנֶה עֶשְׂרֵה שָׁנָה יְהוֹיָכִין בְּמָלְכוֹ וּשְׁלֹשָׁה חֳדָשִׁים מָלַךְ בִּירוּשָׁלִָם וְשֵׁם אִמּוֹ נְחֻשְׁתָּא בַת אֶלְנָתָן מִירוּשָׁלִָם.

2 Kgs 24:8 Jehoiachin was eighteen years old when he became king, and he reigned three months in Jerusalem; his mother’s name was Nehushta daughter of Elnathan of Jerusalem.

Jehoiachin’s father, Jehoiakim, had incurred the wrath of the Babylonian king Nebuchadrezzar[1] by continually shifting his loyalties between Babylonia and Egypt. Nebuchadrezzar was determined to punish Jehoiakim for these intolerable vacillations.[2] Jehoiakim appears to have died in the nick of time, however,[3] leaving his young son and successor Jehoiachin to bear the brunt of the Babylonian attacking force, which exiled the royal family plus a large group of elites to Babylonia:

כד:טו וַיֶּגֶל אֶת יְהוֹיָכִין בָּבֶלָה וְאֶת אֵם הַמֶּלֶךְ וְאֶת נְשֵׁי הַמֶּלֶךְ וְאֶת סָרִיסָיו וְאֵת אולי [אֵילֵי] הָאָרֶץ הוֹלִיךְ גּוֹלָה מִירוּשָׁלִַם בָּבֶלָה. כד:טז וְאֵת כָּל אַנְשֵׁי הַחַיִל שִׁבְעַת אֲלָפִים וְהֶחָרָשׁ וְהַמַּסְגֵּר אֶלֶף הַכֹּל גִּבּוֹרִים עֹשֵׂי מִלְחָמָה וַיְבִיאֵם מֶלֶךְ בָּבֶל גּוֹלָה בָּבֶלָה.

24:15 He deported Jehoiachin to Babylon, and the king’s mother, wives, eunuchs, and the notables of the land he brought into exile from Jerusalem to Babylon. 24:16 All the able men, to the number of seven thousand – all of them warriors trained for battle – and a thousand craftsmen and smiths were brought to Babylon as exiles by the king of Babylon.[4]

Jehoiachin Surrenders on the 2nd of Adar

The biblical text does not provide a more precise time frame for Jehoiachin’s three-month reign and Nebuchadnezzar’s attack.

מלכים ב כד:י בָּעֵת הַהִיא עלה [עָלוּ] עַבְדֵי נְבֻכַדְנֶאצַּר מֶלֶךְ בָּבֶל יְרוּשָׁלִָם וַתָּבֹא הָעִיר בַּמָּצוֹר. כד:יא וַיָּבֹא נְבוּכַדְנֶאצַּר מֶלֶךְ בָּבֶל עַל הָעִיר וַעֲבָדָיו צָרִים עָלֶיהָ. כד:יב וַיֵּצֵא יְהוֹיָכִין מֶלֶךְ יְהוּדָה עַל מֶלֶךְ בָּבֶל הוּא וְאִמּוֹ וַעֲבָדָיו וְשָׂרָיו וְסָרִיסָיו וַיִּקַּח אֹתוֹ מֶלֶךְ בָּבֶל בִּשְׁנַת שְׁמֹנֶה לְמָלְכוֹ.

2 Kgs 24:10 At that time, the troops of King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon marched against Jerusalem, and the city came under siege. 24:11 King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon advanced against the city while his troops were besieging it. 24:12 Thereupon King Jehoiachin of Judah, along with his mother and his courtiers, commanders and officers, surrendered to the king of Babylon. The king of Babylon took him captive in the eighth year of his reign.[5]

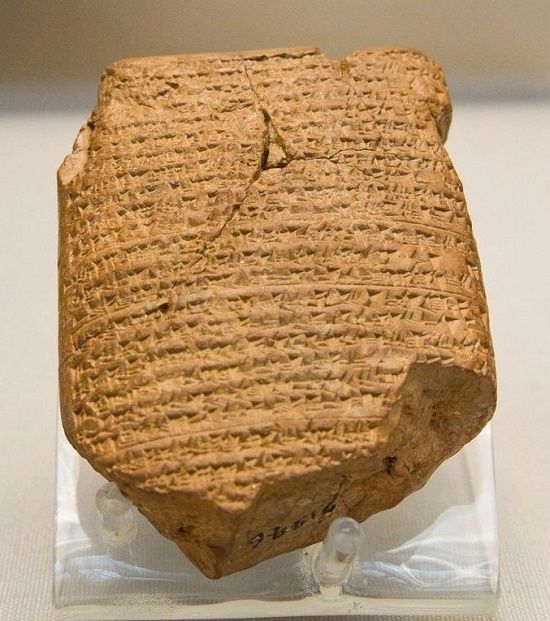

The Akkadian text known as the Babylonian Chronicle Number 5[6] fills in the missing details as follows:[7]

The seventh year [of Nebuchadrezzar]:[8] In the month of Kislev the king of Akkad mustered his army and marched to Hattu.[9] He encamped against the city of Judah (i.e. Jerusalem) and on the second day of the month of Adar, he captured the city and seized the king. A king of his own choice he appointed in the city and taking the vast tribute, he brought it into Babylon.

This invaluable source identifies the date of Jehoiachin’s surrender as the second of Adar in Nebuchadrezzar’s seventh regnal year (March 15th 597 B.C.E.), thus allowing us to frame Jehoiachin’s reign as encompassing the months of Kislev, Tevet, and Shevat at the juncture of the years 598–597 B.C.E.[10]

Babylonians Recognize Two Kings of Judah

The Babylonians appointed Jehoiachin’s uncle as king in Judah:

מלכים ב כד:יז וַיַּמְלֵךְ מֶלֶךְ בָּבֶל אֶת מַתַּנְיָה דֹדוֹ תַּחְתָּיו וַיַּסֵּב אֶת שְׁמוֹ צִדְקִיָּהוּ.

2 Kgs 24:17 And the king of Babylon appointed Mattaniah, Jehoiachin’s uncle, king in his place, changing his name to Zedekiah.

Yet at the same time we know, from administrative texts referring to the food rations that Jehoiachin and his sons were assigned in prison, that the Babylonians themselves continued to refer to Jehoiachin as the king of Judah, even while he and his sons were incarcerated.[11] We do not know if the Babylonian practice of recognizing two kings of Judah was intended to have a “divide and conquer” effect, or if it was designed to impress upon Zekediah—the king of Nebuchadrezzar’s own choice, as the Babylonian Chronicle puts it—that he was essentially ruling on probation.

Two Kings– Two Judean Peoples?

The exile of the eighteen year old king and the cohort of Judean nobility that went with him set into motion an unprecedented situation of two separate, and to a great extent rival, communities of Judeans – one which remained in Jerusalem under the leadership of the Babylonian-sponsored king Zedekiah, and the other which was deported to Babylonia along with Jehoiachin and his entourage.

Ezekiel – Prophet of the Jehoiachin Exile

The deportee most well-known to us besides Jehoiachin himself was the prophet Ezekiel, who describes his famous prophecy of initiation (the so-called chariot vision) as having occurred while he was among the exiles on the Khebar canal:

יחזקאל א:ב בַּחֲמִשָּׁה לַחֹדֶשׁ הִיא הַשָּׁנָה הַחֲמִישִׁית לְגָלוּת הַמֶּלֶךְ יוֹיָכִין.

Ezek 1:2 On the fifth day of the month — it was the fifth year of the exile of King Jehoiachin.

This corresponds to the summer of 593, and is the first of many prophecies in Ezekiel that are dated according to the number of years that had passed since Jehoiachin’s exile (see also Ezek. 8:1; 20:1; 24:1; 26:1; 29:1, 17, etc.). This dating system not only gives expression to a longing for the homeland, but seems to reflect a counting of actual regnal years that were assigned to Jehoiachin by the fledging Babylonian Judean community. In other words, the exiles adopted a unique dating system as an expression of their particular communal identity as well as of their ongoing loyalty to Jehoiachin.

The Bible preserves a lively debate regarding the significance of Jehoiachin’s exile.[12] At stake was not only which individual was to be viewed as the legitimate king—Zedekiah or Jehoiachin—but even more significantly, which community was to be viewed as the legitimate people of God, those who remained in Jerusalem or those who had been deported to Babylonia in 597.

Hananiah’s Prophecy – Jehoiachin is Coming Back

For the fervent nationalists, whom Jeremiah regards as false prophets, the physical separation of the two Judean communities was viewed as a passing phase soon to be resolved. Thus, the book of Jeremiah records the words of his prophetic rival Hananiah son of Azur:[13]

ירמיה כח:ב כֹּה אָמַר יְהוָה צְבָאוֹת אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל לֵאמֹר שָׁבַרְתִּי אֶת עֹל מֶלֶךְ בָּבֶל. כח:ג בְּעוֹד שְׁנָתַיִם יָמִים אֲנִי מֵשִׁיב אֶל הַמָּקוֹם הַזֶּה אֶת כָּל כְּלֵי בֵּית יְהוָה אֲשֶׁר לָקַח נְבוּכַדנֶאצַּר מֶלֶךְ בָּבֶל מִן הַמָּקוֹם הַזֶּה וַיְבִיאֵם בָּבֶל. כח:ד וְאֶת יְכָנְיָה בֶן יְהוֹיָקִים מֶלֶךְ יְהוּדָה וְאֶת כָּל גָּלוּת יְהוּדָה הַבָּאִים בָּבֶלָה אֲנִי מֵשִׁיב אֶל הַמָּקוֹם הַזֶּה נְאֻם יְהוָה…

Jer 28:2 Thus said the Lord of Hosts, the God of Israel: I hereby break the yoke of the king of Babylon. 28:3 In two years, I will restore to this place all the vessels of the house of the Lord which King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon took from this place and brought to Babylon. 28:4 And I will bring back to this place King Jeconiah (=Jehoiachin) son of Jehoiakim of Judah, and all the Judean exiles who went to Babylon, declares the Lord…

Hananiah’s prophecy shows that some Judeans related to Zekediah as a temporary place-holder king, and believed that Jehoiachin would eventually come back to Judah and retake the throne.

Shemaiah’s Letter: Stop Jeremiah

This stance was shared by another prophet, Shemaiah the Nehelamite,[14] who as a member of the Judean community already in Babylonia, objected to Jeremiah’s missive encouraging the Babylonian Judeans to prepare for an extended sojourn in exile. Shemaiah’s machinations against Jeremiah along with Jeremiah’s reaction are reported in God’s rebuke to Shemaiah, which he tells Jeremiah (Jer. 29:24–32):

God tells Jeremiah a message for Shemaiah.

ירמיה כט:כד וְאֶל שְׁמַעְיָהוּ הַנֶּחֱלָמִי תֹּאמַר לֵאמֹר. כט:כה כֹּה אָמַר יְ-הוָה צְבָאוֹת אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל לֵאמֹר

Jer 29:24 Concerning Shemaiah the Nehelamite you shall say: 29:25 Thus said the Lord of Hosts, the God of Israel:

Shemaiah wrote a letter to Zephaniah and the priests of Jerusalem.

יַעַן אֲשֶׁר אַתָּה שָׁלַחְתָּ בְשִׁמְכָה סְפָרִים אֶל כָּל הָעָם אֲשֶׁר בִּירוּשָׁלִַם וְאֶל צְפַנְיָה בֶן מַעֲשֵׂיָה הַכֹּהֵן וְאֶל כָּל הַכֹּהֲנִים לֵאמֹר.

Because you sent letters in your own name to all the people in Jerusalem, to Zephaniah son of Maaseiah and to the rest of the priests as follows,

“You should have locked up Jeremiah, who says crazy things.”

כט:כו יְ-הוָה נְתָנְךָ כֹהֵן תַּחַת יְהוֹיָדָע הַכֹּהֵן לִהְיוֹת פְּקִדִים בֵּית יְ-הוָה לְכָל אִישׁ מְשֻׁגָּע וּמִתְנַבֵּא וְנָתַתָּה אֹתוֹ אֶל הַמַּהְפֶּכֶת וְאֶל הַצִּינֹק. כט:כז וְעַתָּה לָמָּה לֹא גָעַרְתָּ בְּיִרְמְיָהוּ הָעֲנְּתֹתִי הַמִּתְנַבֵּא לָכֶם.

29:26 ‘The Lord appointed you priest in place of the priest Jehoiada to exercise authority in the house of the Lord over every madman who wants to play the prophet, to put him into the stocks and into the pillory. 29:27 Now why have you not rebuked Jeremiah the Anathotite who plays the prophet among you?

Jeremiah wrote to the Babylonian exiles saying they should be prepared for the long haul.

כט:כח כִּי עַל כֵּן שָׁלַח אֵלֵינוּ בָּבֶל לֵאמֹר אֲרֻכָּה הִיא בְּנוּ בָתִּים וְשֵׁבוּ וְנִטְעוּ גַנּוֹת וְאִכְלוּ אֶת פְּרִיהֶן.

29:28 For he has actually sent a message to us in Babylon to this effect: It will be a long time. Build houses and live in them, plant gardens and enjoy their fruit.’

Zephaniah reads Shemaiah’s letter to Jeremiah.

כט:כט וַיִּקְרָא צְפַנְיָה הַכֹּהֵן אֶת הַסֵּפֶר הַזֶּה בְּאָזְנֵי יִרְמְיָהוּ הַנָּבִיא.

29:29 The priest Zephaniah read this letter in the hearing of the prophet Jeremiah,

God gives Jeremiah a message for the exiles about Shemaiah:

כט:ל וַיְהִי דְּבַר יְ-הוָה אֶל יִרְמְיָהוּ לֵאמֹר. כט:לא שְׁלַח עַל כָּל הַגּוֹלָה לֵאמֹר כֹּה אָמַר יְ-הוָה אֶל שְׁמַעְיָה הַנֶּחֱלָמִי

29:30 and the word of the Lord came to Jeremiah:29:31 Send a message to the entire exile community, thus said the Lord concerning Shemaiah the Nehelamite:

Shemaiah is a false prophet and God will destroy him and his offspring for eternity.

יַעַן אֲשֶׁר נִבָּא לָכֶם שְׁמַעְיָה וַאֲנִי לֹא שְׁלַחְתִּיו וַיַּבְטַח אֶתְכֶם עַל שָׁקֶר. כט:לב לָכֵן כֹּה אָמַר יְ-הוָה הִנְנִי פֹקֵד עַל שְׁמַעְיָה הַנֶּחֱלָמִי וְעַל זַרְעוֹ לֹא יִהְיֶה לוֹ אִישׁ יוֹשֵׁב בְּתוֹךְ הָעָם הַזֶּה וְלֹא יִרְאֶה בַטּוֹב אֲשֶׁר אֲנִי עֹשֶׂה לְעַמִּי נְאֻם יְ-הוָה כִּי סָרָה דִבֶּר עַל יְ-הוָה.

Because Shemaiah prophesied to you, though I did not send him and made you false promises, 29:32 assuredly thus said the Lord, I am going to punish Shemaiah the Nehelamite and his offspring. There shall be no man of his line dwelling among this people or seeing the good things I am going to do for my people, declares the Lord, for he has urged disloyalty toward the Lord.

This letter shows that at least some in the Babylonian community believed that their stay in Babylon would be short lived, and that they objected to claims of people like Jeremiah telling them to get comfortable in exile.

A Permanent Rejection of Jehoiachin

As opposed to the expectation that Jehoiachin and his fellow exiles would be restored soon to Jerusalem, there were those, especially among the Jerusalem community, who interpreted the events of 597 as indicating that God had rejected Jehoiachin and those exiled with him. This point of view is cited most succinctly (and disapprovingly) in Ezekiel 11:14–15:

יחזקאל יא:יד וַיְהִי דְבַר יְ-הוָה אֵלַי לֵאמֹר. יא:טו בֶּן אָדָם אַחֶיךָ אַחֶיךָ אַנְשֵׁי גְאֻלָּתֶךָ וְכָל בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל כֻּלֹּה אֲשֶׁר אָמְרוּ לָהֶם יֹשְׁבֵי יְרוּשָׁלִַם רַחֲקוּ מֵעַל יְ-הוָה לָנוּ הִיא נִתְּנָה הָאָרֶץ לְמוֹרָשָׁה.

Ezek 11:14 Then the word of the Lord came to me. O mortal, your brothers, your brothers, your kinsmen, and all the house of Israel [in exile] to whom the inhabitants of Jerusalem say, “They have been distanced from the Lord, the land has been given to us a heritage.”

This citation appears in the context of an extended vision covering four chapters (Ezek 8–11) that is dated to the sixth year of Jehoiachin’s exile, i.e. 592. In other words, at the height of Zedekiah’s eleven year reign, certain Jerusalemites concluded that the exile of their fellow Judeans along with Jehoiachin was a sure sign of their permanent estrangement from God and his land.

It is easy to characterize this condescending attitude as stemming from sheer political opportunism, inasmuch as the Judeans remaining in Jerusalem likely filled the positions and properties vacated by the exiles. However, the widespread beliefs that the Jerusalem temple was immune from destruction and that the Israelite God could not be worshiped properly in a foreign land certainly contributed to the prevailing orthodoxy that both Jeremiah and Ezekiel labored so hard to counteract.[15] This orthodoxy suggested, quite simply, that exile of a particular group suggested Divine disfavor with them.

Sympathizing with Jehoiachin’s Group

In a general way, both of the great prophets of the period showed greater sympathy toward the Jehoiachin-led Babylonian Judean community than they did toward the Zedekiah-led community in Jerusalem.[16] That said, even the book of Ezekiel, which was produced within the Jehoiachin-led Babylonian community, contains no shortage of harsh words for the Babylonian Judean community as well.[17]

It seems safe to say, however, that both Jeremiah and Ezekiel viewed the best hope for a reconstituted Israel as emerging from those Judeans who were exiled with Jehoiachin (see in particular Jeremiah 24 and Ezekiel 11:16–20).

The Fate of Jehoiachin

Nevertheless, Jeremiah and Ezekiel portray Jehoiachin’s fate in dramatically different fashions.

Jeremiah – Jehoiachin Is Permanently Rejected

Jeremiah’s prognosis for Jehoiachin is completely bleak. An extended tirade against Jehoiachin harshly condemns him (Jer. 22:24–30):

ירמיה כב:כד חַי אָנִי נְאֻם יְ-הוָה כִּי אִם יִהְיֶה כָּנְיָהוּ בֶן יְהוֹיָקִים מֶלֶךְ יְהוּדָה חוֹתָם עַל יַד יְמִינִי כִּי מִשָּׁם אֶתְּקֶנְךָּ. כב:כה וּנְתַתִּיךָ בְּיַד מְבַקְשֵׁי נַפְשֶׁךָ וּבְיַד אֲשֶׁר אַתָּה יָגוֹר מִפְּנֵיהֶם וּבְיַד נְבוּכַדְרֶאצַּר מֶלֶךְ בָּבֶל וּבְיַד הַכַּשְׂדִּים. כב:כו וְהֵטַלְתִּי אֹתְךָ וְאֶת אִמְּךָ אֲשֶׁר יְלָדַתְךָ עַל הָאָרֶץ אַחֶרֶת אֲשֶׁר לֹא יֻלַּדְתֶּם שָׁם וְשָׁם תָּמוּתוּ.

Jer 22:24 As I live, declares the Lord, if you, O Coniah son of Jehoiakim of Judah were a signet on my right hand, I would tear you off even from there. 22:25 I will deliver you into the hands of those who seek your life, into the hands of those you dread, into the hands of King Nebuchadrezzar of Babylon and into the hands of the Chaldeans. 22:26 I will hurl you and the mother who bore you into another land where you were not born; there you shall both die.[18]

This prophecy ends with a final declaration:

כב:כט אֶרֶץ אֶרֶץ אָרֶץ שִׁמְעִי דְּבַר יְ-הוָה. כב:ל כֹּה אָמַר יְ-הוָה כִּתְבוּ אֶת הָאִישׁ הַזֶּה עֲרִירִי גֶּבֶר לֹא יִצְלַח בְּיָמָיו כִּי לֹא יִצְלַח מִזַּרְעוֹ אִישׁ יֹשֵׁב עַל כִּסֵּא דָוִד וּמֹשֵׁל עוֹד בִּיהוּדָה.

22:29 O land, land, land, hear the word of the Lord. 22:30 Thus said the Lord: Record this man as without succession, one who shall not prosper in his days, for no man of his seed shall prosper to sit on the throne of David and to rule again in Judah.

Thus, Jeremiah believes that Jehoiachin will be utterly rejected.[19]

Ezekiel – A Descendent of Jehoiachin Will Rule Again

Contrariwise, Ezekiel, who as we saw above, dated his prophecies to Jehoiachin’s regnal years, envisions a future return of a descendant of the exiled king to his homeland. This hopeful message emerges from the conclusion of the parable of the two eagles in Ezekiel chapter 17. It begins by relating how the first eagle (representing Nebuchadrezzar) carried away the uppermost bough of a tall cedar tree (representing Jehoiachin). Ultimately, however, God himself promises to take a tender twig from the tip of the cedar’s crown and replant it on the mountains of Israel (Ezek. 17:22–23):

יחזקאל יז:כב כֹּה אָמַר אֲדֹנָי יְהוִה וְלָקַחְתִּי אָנִי מִצַּמֶּרֶת הָאֶרֶז הָרָמָה וְנָתָתִּי מֵרֹאשׁ יֹנְקוֹתָיו רַךְ אֶקְטֹף וְשָׁתַלְתִּי אָנִי עַל הַר גָּבֹהַ וְתָלוּל. יז:כג בְּהַר מְרוֹם יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶשְׁתֳּלֶנּוּ וְנָשָׂא עָנָף וְעָשָׂה פֶרִי וְהָיָה לְאֶרֶז אַדִּיר וְשָׁכְנוּ תַחְתָּיו כֹּל צִפּוֹר כָּל כָּנָף בְּצֵל דָּלִיּוֹתָיו תִּשְׁכֹּנָּה.

Ezek 17:22 Thus says the Lord God: But I will take of the lofty crown of a cedar and put it; from its topmost shoots I will pluck a tender twig and plant it on a high and towering mountain. 17:23 In the mountainous heights of Israel I will plant it. It will bear branches and produce fruit and become a noble cedar. Every bird of every wing shall dwell beneath it, in the shadow of its branches they shall dwell.

In other words, while the upper bough of the cedar (representing Jehoiachin) will not be brought back whole, God does promise that at least a small offshoot of the bough (representing a descendant of Jehoiachin) will return to the land of Israel and achieve prominence there. The optimism expressed in this passage stands in stark contrast to Jeremiah’s words of unmitigated doom toward Jehoiachin and his descendants.[20]

Jehoiachin Freed from Prison in Adar

So was there a “happy ending” for Jehoiachin? Was his family given a future in Judean leadership? This question cannot be answered conclusively due to the enigmatic nature of the sources at our disposal.

The much-debated last paragraph of the Book of Kings tells of Jehoiachin’s eventual release from prison (2 Kings 25:27–30):

מלכים ב כה:כז וַיְהִי בִשְׁלֹשִׁים וָשֶׁבַע שָׁנָה לְגָלוּת יְהוֹיָכִין מֶלֶךְ יְהוּדָה בִּשְׁנֵים עָשָׂר חֹדֶשׁ בְּעֶשְׂרִים וְשִׁבְעָה לַחֹדֶשׁ נָשָׂא אֱוִיל מְרֹדַךְ מֶלֶךְ בָּבֶל בִּשְׁנַת מָלְכוֹ אֶת רֹאשׁ יְהוֹיָכִין מֶלֶךְ יְהוּדָה מִבֵּית כֶּלֶא.

2 Kgs 25:27 In the thirty-seventh year of the exile of King Jehoiachin of Judah, on the twelfth month on the twenty-seventh day of the month, King Evil-merodach of Babylon, in the year he became king, took note of King Jehoiachin of Judah and released him from prison.

The new Babylonian king Evil-merodach (Akkadian Amel-Marduk), who succeeded his father Nebuchadrezzar, declared an immediate amnesty for Jehoiachin. Ironically, Jehoiachin’s release is said to have taken place in the twelfth month (i.e. Adar), just like his capture thirty-seven years earlier. This provides a notable historical precedent for the changing fortunes of the month of Adar known famously from the Purim story (Esther 9:22).

The Ambiguous Message of the Ending of Kings

It is not entirely clear, however, what message the author of 2 Kings 25:27–30 was trying to convey.

כה:כח וַיְדַבֵּר אִתּוֹ טֹבוֹת וַיִּתֵּן אֶת כִּסְאוֹ מֵעַל כִּסֵּא הַמְּלָכִים אֲשֶׁר אִתּוֹ בְּבָבֶל. כה:כט וְשִׁנָּא אֵת בִּגְדֵי כִלְאוֹ וְאָכַל לֶחֶם תָּמִיד לְפָנָיו כָּל יְמֵי חַיָּיו. כה:ל וַאֲרֻחָתוֹ אֲרֻחַת תָּמִיד נִתְּנָה לּוֹ מֵאֵת הַמֶּלֶךְ דְּבַר יוֹם בְּיוֹמוֹ כֹּל יְמֵי חַיָּו.

25:28 He spoke kindly to him and gave him a throne above those of other kings who were with him in Babylon. 25:29 His prison garments were removed and he received regular rations by his favor for the rest of his life. 25:30 A regular allotment of food was given him at the instance of the king, an allotment for each day, all the days of his life.

The fact that Jehoiachin was released from prison does not in and of itself indicate that he or his sons were being groomed for a return to the Judean throne. At most, the author of this passage, who was in all likelihood writing in the Babylonian diaspora himself, was signaling to his fellow Judeans that their collective national fortunes were taking a turn for the better and that God was giving them an opening, so to speak, to engage in full repentance.[21]

The Importance of Zerubbabel

Another set of texts related to the fate and status of Jehoiachin’s family centers around the figure of Zerubbabel, first governor of Judah, mentioned in the context of the second year of the Persian king Darius I (520 B.C.E.), at which time he played an active part in the rebuilding of the Second Temple (Hag 1:14–15; see also Zech 4:8–10).[22]

Zerubbabel is directly linked genealogically to Jehoiachin in the Chronicler’s list of Davidic royal descendants (1 Chron. 3:17–19):

דברי הימים א ג:יז וּבְנֵי יְכָנְיָה אַסִּר שְׁאַלְתִּיאֵל בְּנוֹ. ג:יח וּמַלְכִּירָם וּפְדָיָה וְשֶׁנְאַצַּר יְקַמְיָה הוֹשָׁמָע וּנְדַבְיָה. ג:יט וּבְנֵי פְדָיָה זְרֻבָּבֶל וְשִׁמְעִי…

1 Chron 3:17 And the sons of Jeconiah the captive: Shealtiel his son, 3:18 Malkiram, Pedaiah, Shenazzar, Jekamiah, Hoshama, and Nedabiah. 3:19 The sons of Pedaiah: Zerubbabel and Shimei …”[23]

Indeed, the prophet Haggai in particular appears to have held out high hopes for Zerubbabel in a passage dated to Darius’s second year (Hag. 2:20–23) that many scholars view as a direct rebuttal to Jeremiah 22:24–30 (see above).[24]

חגי ב:כ וַיְהִי דְבַר יְהוָה שֵׁנִית אֶל חַגַּי בְּעֶשְׂרִים וְאַרְבָּעָה לַחֹדֶשׁ לֵאמֹר. ב:כא אֱמֹר אֶל זְרֻבָּבֶל פַּחַת יְהוּדָה לֵאמֹר אֲנִי מַרְעִישׁ אֶת הַשָּׁמַיִם וְאֶת הָאָרֶץ. ב:כב וְהָפַכְתִּי כִּסֵּא מַמְלָכוֹת וְהִשְׁמַדְתִּי חֹזֶק מַמְלְכוֹת הַגּוֹיִם וְהָפַכְתִּי מֶרְכָּבָה וְרֹכְבֶיהָ וְיָרְדוּ סוּסִים וְרֹכְבֵיהֶם אִישׁ בְּחֶרֶב אָחִיו. ב:כג בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא נְאֻם יְהוָה צְבָאוֹת אֶקָּחֲךָ זְרֻבָּבֶל בֶּן שְׁאַלְתִּיאֵל עַבְדִּי נְאֻם יְהוָה וְשַׂמְתִּיךָ כַּחוֹתָם כִּי בְךָ בָחַרְתִּי נְאֻם יְהוָה צְבָאוֹת.

Hag 2:20 And the word of the Lord came to Haggai a second time on the twenty-fourth day of the month: 2:21 Speak to Zerubbabel the governor of Judah, I am going to shake the heavens and the earth. 2:22 And I will overturn the thrones of kingdoms and destroy the might of the kingdoms of the nations. I will overturn chariots and their drivers; horses and their riders shall fall, each by the sword of his fellow. 2:23 On that day, declares the Lord of Hosts, I will take you, O my servant Zerubbabel son of Shealtiel, declares the Lord, and make you as a signet, for I have chosen you, declares the Lord of Hosts.

Despite this optimistic prediction, Zerubbabel vanishes from the scene. Much ink has been spilled speculating on the circumstances of Zerubbabel’s sudden disappearance.[25] One thing is clear, though, namely that neither Zerubbabel, nor any of his descendants, achieved royal status in restored Judea. At the same time, there can be no doubt that certain of Jehoiachin’s descendants, with Zerubbabel being chief among them, did in fact merit to return to the land of their forefathers. This modest but meaningful achievement is symbolic of the enduring resilience of the people of Israel.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 28, 2017

|

Last Updated

February 9, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. David A. Glatt-Gilad taught for thirty years in the Department of Bible, Archaeology, and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Ben-Gurion University in the Negev, specializing in Deuteronomistic literature and Chronicles. Currently, he has commenced work on a book to be entitled History and Faith: 'Biblical Criticism' and the Modern, Traditional Jew.

Essays on Related Topics: