Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Mikra Mesuras: Anastrophe, a Literary Feature in the Bible

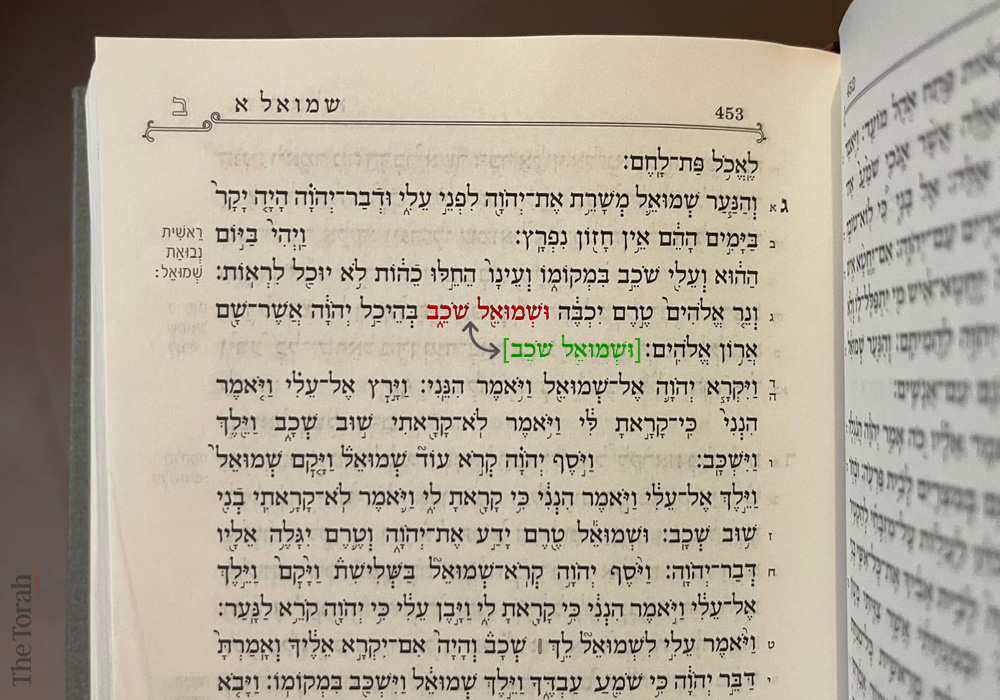

Example of mikra mesuras: In 1 Samuel 3:3, the phrase וּשְׁמוּאֵל שֹׁכֵב “and Samuel was sleeping” should come at the end of the verse but was placed earlier to convey a message.

The prophet Samuel grows up under the care of Eli, the elderly priest of Shiloh, at a time when prophecy is rare (1 Sam 3:1). One night, when Samuel was still a lad, the Lord decides to speak to him:

שמואל א ג:ב וַיְהִי בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא וְעֵלִי שֹׁכֵב בִּמְקוֹמוֹ וְעֵינָו הֵחֵלּוּ כֵהוֹת לֹא יוּכַל לִרְאוֹת. ג:ג וְנֵר אֱלֹהִים טֶרֶם יִכְבֶּה וּשְׁמוּאֵל שֹׁכֵב בְּהֵיכַל יְ־הֹוָה אֲשֶׁר שָׁם אֲרוֹן אֱלֹהִים. ג:ד וַיִּקְרָא יְ־הֹוָה אֶל שְׁמוּאֵל וַיֹּאמֶר הִנֵּנִי.

1 Sam 3:2 One day, Eli was asleep in his usual place; his eyes had begun to fail and he could barely see. 3:3 The lamp of God had not yet gone out, and Samuel was sleeping in the temple of the LORD where the Ark of God was. 3:4 And the LORD called out to Samuel, and he answered, “I’m here.” [1]

The Talmud notes that Samuel violates the rules of proper treatment of holy places and objects by sleeping in the Temple, and thus the verse should be read as if the phrase “Samuel was sleeping” is out of place:

בבלי קדושין עח: וַהֲלֹא אֵין יְשִׁיבָה בַּעֲזָרָה אֶלָּא לְמַלְכֵי בֵית דָּוִד בִּלְבַד! אֶלָּא: ״נֵר אֱלֹהִים טֶרֶם יִכְבֶּה בְּהֵיכַל ה׳ [אֲשֶׁר שָׁם אֲרוֹן אֱלֹהִים], וּשְׁמוּאֵל שֹׁכֵב״ – בִּמְקוֹמוֹ.

b. Kiddushin 78b But aren’t the Davidic kings the only ones permitted to dwell in the temple precincts?! Rather [this is how the verse should be read]: “the lamp of God had not yet gone out in the Temple of the LORD [where the Ark of God was], and Samuel was sleeping”—in his place.[2]

In other words, the Talmud disconnects the clause about Samuel sleeping, reading it as an independent statement. Reordering the verse thus, it is only the lamp that is inside the temple with the ark, while Samuel is sleeping wherever it is he usually sleeps, but not in the temple precinct.

Straightforward Readings

The commentator R. Levi Gersonides (Ralbag 1288–1344), however, reads the verse according to its order:

רלב"ג, שמואל א ג:ג והנה טרם שכבה נר אלהים והוא אצל עליית השחר היה שמואל שוכב אצל היכל י"י אשר שם ארון האלהים בלשכה אחת היתה שם ובעת הזה המוכן בהגעת החלומות הצודקים החלה להגיע אליו הנבואה.

Ralbag 1 Sam 3:3 Now, the time when the lamp of God is about to burn out is around dawn, and Samuel was sleeping at the Temple of the LORD where the Ark of God was to be found—it was kept in a room there. At this time [of night], which that is ripe for the appearance of true dreams, is when prophecy first came to him. [3]

While Gersonides follows the order of the verse, his interpretation avoids stating that Samuel slept in the room with the ark by translating the preposition ב as אצל “by” rather than “in,” and suggesting that the ark was in a different room.

In contrast, Arnold Ehrlich (1848–1919), in a long polemical gloss, argues that the verse means exactly what it says:

מקרא כפשוטו שמואל א ג:ג ועתה הלא תראה שהכתוב כסדר הזה אשר לפנינו חכם מכל החכמים הראשונים והאחרונים המסרסים אותו? כי הכתוב מדבר בימים הראשונים ההם כראוי לימי קדם, והמסרסים אותו כל הימים שוים בעיניהם.

Mikra Ki-Pheshuto 1 Sam 3:3 And now don’t you see that the verse understood as it is written before us is wiser than all the wise ones, early and late, who reorganize it. For scripture is speaking about past days—as is fitting for a text from ancient times— and those who reorganize it treat all time periods as if they were the same.

ומפני שאנחנו זרה לנו היום הזה מחשבת שכיבה בהיכל ה', הם אומרים שהיתה מחשבה כמחשבה זאת זרה גם לעברים בימי קדם.

So, since the idea of someone sleeping in the Temple of the LORD is unseemly to us, [these sages] say that such a thought was also unseemly to the ancient Hebrews.

Nevertheless, the Talmudic reading is accepted by the masoretic scribes who attached cantillation and punctuation notes (טעמי המקרא), as they placed the etnachta (major pause) beneath the word “sleeping,”—וּשְׁמוּאֵ֖ל שֹׁכֵ֑ב—essentially cutting this phrase off from the following one, “in the Temple.”

The 31st Principle of Interpretation

The thirty-first of R. Eliezer son of Rabbi Yossi HaGelili’s thirty-two rules of exegesis: מוקדם שהוא מאוחר בענין, i.e., early placement of words that (substantively or syntactically) belong later in the verse, refers to “anastrophe,” an inversion of the usual order of words or clauses.[4] The later commentary to this work, found in the first two chapters of Mishnat Rabbi Eliezer (late first millennium C.E.) uses the verse in Samuel as its parade example for this exegetical principle:

משנת רבי אליעזר (פרשה ב) לב "ממוקדם ומאוחר שהוא בענין" כיצד? "ונר אלהים טרם יכבה ושמואל שוכב בהיכל יוי [אשר שם ארון אלהים]" (שמואל א ג:ג)—והלא אין ישיבה בעזרה אלא למלכי בית דוד, שנ' (שמואל ב ז:יח) "ויבא המלך דוד וישב לפני יוי ויאמר מי וגו'." ומה ת"ל "ושמואל שוכב בהיכל יוי." אלא מוקדם הוא, ונר אלהים טרם יכבה ושמואל שוכב במקומו.

Mishnat Rabbi Eliezer (ch. 2) §32 What is an example of early placement which is connected to later? “The lamp of God had not yet gone out, and Samuel was sleeping in the temple of the LORD [where the Ark of God was]”—But [even]sitting in the courtyard is only permitted to the Davidic kings! As it says (2 Sam 7:18): “Then King David came and sat before the LORD, and he said...” So what does it mean “and Samuel was sleeping in the Temple of the LORD”? It is placed early, the lamp of God had not yet gone out [in the Temple of the LORD], and Samuel was sleeping wherever he usually slept [outside the Temple].[5]

Like the Talmud, the midrash suggests the verse be restructured, connecting the first and third clauses, so that the specification “in the Temple” describes the location of the candle, not where Samuel was sleeping.

Midrashic Explanation for the Anastrophe: An Allegory

The medieval exegete R. David Kimhi (Radak, ca. 1160–ca. 1235) offers an allegorical explanation of “lamp,” to explain why the verse would be written in a jumbled order:

רד"ק שמואל א ג:ג ובמדרש (בראשית רבה נח) אמר כי על נר הנבואה אמר, ואמרו (קהלת א:ה) "וזרח השמש ובא השמש" עד שלא ישקיע הקב”ה שמשו של צדיק אחד הוא מזריח שמשו של צדיק אחר, עד שלא ישקיע שמשו של משה מזריח שמשו של יהושע עד שלא תשקע שמשו של עלי תזריח שמשו של שמואל וזהו שאמר ונר אלקים טרם יכבה: ושמואל שוכב בהיכל ה’.

Radak 1 Sam 3:3 In the midrash (Gen Rab 58) it states that the passage is referring to the lamp of prophecy. And they said: “And the sun shone and the sun set” (Eccl 1:5): before God sets the sun of one righteous man, God brings forth the light of another. Before God made the sun of Moses set, God raised the sun of Joshua; before making the sun of Eli set, God made the sun of Samuel rise, and this is what was stated (1 Sam 3:3) “And the candle of God was not yet extinguished and Samuel lay in the Temple of the Lord.”[6]

In this allegorical reading, “the candle of God,” referring to Eli’s dimming prophetic powers, comes immediately before the reference to Samuel sleeping, expressing that Eli’s replacement, Samuel, was literally and figuratively “waiting in the wings.” Because Eli has faltered (2:22–2:36), the premature transition of prophetic leadership to Samuel is necessary, even though he is being called upon before he has come of age or is psychologically prepared for the task (3:5–8).[7]

In other words, darkness is about to engulf the prophetic light, but just before the last flicker is extinguished, God calls out to the young sleeping Samuel: the boy’s sleep is a further continuation of the metaphor of prophetic vision. Samuel is unprepared for the conferral of prophetic power, but the circumstances leave God no choice: He must prematurely arouse the boy’s slumbering prophetic potential. It is precisely the jumbled syntax (as the rabbis understood it), the intentional use of anastrophe that provokes the metaphorical reading.

Whether one accepts the reorganization of the verse as peshat or merely as a necessary move to avoid the problematic implication of Samuel sleeping near the ark, the phenomenon to which R. Eliezer’s 31st rule of interpretation points is well attested in commentaries of both Rashi and, to a greater extent, Nachmanides, who rearrange the word order of difficult verses to make sense of them, a phenomenon they call מקרא מסורס (mikra mesuras), “jumbled (literally ‘castrated’) scripture.”[8] To illustrate, we will look at two further examples.

With Lot, His Nephew

After the Lord tells Abram to leave his homeland, he departs for Canaan with his family:

בראשית יב:ה וַיִּקַּח אַבְרָם אֶת שָׂרַי אִשְׁתּוֹ וְאֶת לוֹט בֶּן אָחִיו וְאֶת כׇּל רְכוּשָׁם אֲשֶׁר רָכָשׁוּ וְאֶת הַנֶּפֶשׁ אֲשֶׁר עָשׂוּ בְחָרָן, וַיֵּצְאוּ לָלֶכֶת אַרְצָה כְּנַעַן...

Gen 12:5 Abram took his wife Sarai and his brother’s son Lot, and all the wealth that they had amassed, and the persons that they had acquired in Haran; and they set out for the land of Canaan....

After their brief trip into Egypt, we again hear of Abram travelling with his family, but this time, Lot is not mentioned after Sarai but after the property:

בראשית יג:א וַיַּעַל אַבְרָם מִמִּצְרַיִם הוּא וְאִשְׁתּוֹ וְכׇל אֲשֶׁר לוֹ וְלוֹט עִמּוֹ הַנֶּגְבָּה.

Gen 13:1 From Egypt, Abram went up, him, and his wife, and all that he possessed, together with Lot, into the Negeb.[9]

The verse should read, “him, and his wife, together with Lot, and all that he possessed.” Yet by placing “his possessions” between Abram and Lot, the text has foreshadowed and eloquently punctuated their alienation and its cause:

בראשית יג:ב וְאַבְרָם כָּבֵד מְאֹד, בַּמִּקְנֶה בַּכֶּסֶף וּבַזָּהָב.... יג:ה וְגַם לְלוֹט הַהֹלֵךְ אֶת אַבְרָם הָיָה צֹאן וּבָקָר וְאֹהָלִים. יג:ו וְלֹא נָשָׂא אֹתָם הָאָרֶץ לָשֶׁבֶת יַחְדָּו כִּי הָיָה רְכוּשָׁם רָב וְלֹא יָכְלוּ לָשֶׁבֶת יַחְדָּו.

Gen 13:2 Now Abram was very rich in cattle, silver, and gold…. 13:5 Lot, who went with Abram, also had flocks and herds and tents, 13:6 so that the land could not support them staying together; for their possessions were so great that they could not remain together.

They still travel together, yet their closeness has been called into question by the text, and full rupture between uncle and nephew is not far away:

בראשית יג:ח וַיֹּאמֶר אַבְרָם אֶל לוֹט אַל נָא תְהִי מְרִיבָה בֵּינִי וּבֵינֶךָ וּבֵין רֹעַי וּבֵין רֹעֶיךָ כִּי אֲנָשִׁים אַחִים אֲנָחְנוּ. יג:ט הֲלֹא כׇל הָאָרֶץ לְפָנֶיךָ הִפָּרֶד נָא מֵעָלָי אִם הַשְּׂמֹאל וְאֵימִנָה וְאִם הַיָּמִין וְאַשְׂמְאִילָה... יג:יא וַיִּבְחַר לוֹ לוֹט אֵת כׇּל כִּכַּר הַיַּרְדֵּן וַיִּסַּע לוֹט מִקֶּדֶם וַיִּפָּרְדוּ אִישׁ מֵעַל אָחִיו.

Gen 13:8 Abram said to Lot, “Let there be no strife between you and me, between my herdsmen and yours, for we are kinsmen. 13:9 Is not the whole land before you? Let us separate: if you go north, I will go south; and if you go south, I will go north.” 13:11 So Lot chose for himself the whole plain of the Jordan, and Lot journeyed eastward. Thus they parted from each other.

In the next chapter, when the city in which Lot lives is attacked, and the four kings take Lot captive, we have a stark example of mikra mesuras, “jumbled scripture”:

בראשית יד:יב וַיִּקְחוּ אֶת לוֹט וְאֶת רְכֻשׁוֹ בֶּן אֲחִי אַבְרָם וַיֵּלֵכוּ וְהוּא יֹשֵׁב בִּסְדֹם.

Gen 14:12 They also took Lot, and his possessions, the son of Abram’s brother, and departed; for he had settled in Sodom.

Standard translations avoid the problem by placing “the son of Abram’s brother” before “his possessions,” but that is not the way the verse is written.[10] Instead the verse highlights how Lot’s concern for material wealth has substantively and syntactically come between him and his position as “nephew of Abraham.” Form has imitated content, and in doing so the medium has merged with and underscored the message.

In short, when first introduced, Lot is introduced לוֹט בֶּן אָחִיו “Lot his brother’s son.” But after the fight about possessions and the resultant separation, his status as nephew is less firm. Even though Abraham continues to regard his nephew as a אח “brother” (14:14) after their separation—rushing to his rescue when the latter is captured in war—the breach is permanent. Their process of alienation from one another, as well as the reason for their separation, is subtly expressed in a superbly artistic use of awkward syntax.

Pharaoh’s Daughter on the Nile

After failing to have the Egyptian midwives kill all the male Hebrew infants, Pharaoh proclaims a decree binding on all Egyptians:

שמות א:כב וַיְצַו פַּרְעֹה לְכׇל עַמּוֹ לֵאמֹר כׇּל הַבֵּן הַיִּלּוֹד הַיְאֹרָה תַּשְׁלִיכֻהוּ וְכׇל הַבַּת תְּחַיּוּן.

Exod 1:22 Then Pharaoh charged all his people, saying, “Every boy that is born you shall throw into the Nile, but let every girl live.”

Around this time, Moses is born and his life is threatened by this decree. Therefore, his mother takes the desperate measure to attempt to save the infant by placing him in a floating basket in the river. With Moses’ sister waiting watchfully from a distance, the passage introduces us to Pharaoh’s own daughter, whom divine providence has clearly brought to the same reedy spot on the bank of the river:

שמות ב:ה וַתֵּרֶד בַּת פַּרְעֹה לִרְחֹץ עַל הַיְאֹר וְנַעֲרֹתֶיהָ הֹלְכֹת עַל יַד הַיְאֹר וַתֵּרֶא אֶת הַתֵּבָה בְּתוֹךְ הַסּוּף וַתִּשְׁלַח אֶת אֲמָתָהּ וַתִּקָּחֶהָ. ב:ו וַתִּפְתַּח וַתִּרְאֵהוּ אֶת הַיֶּלֶד וְהִנֵּה נַעַר בֹּכֶה וַתַּחְמֹל עָלָיו וַתֹּאמֶר מִיַּלְדֵי הָעִבְרִים זֶה.

Exod 2:5 The daughter of Pharaoh came down to bathe in the Nile, while her maidens walked along the Nile. She spied the basket among the reeds and sent her slave girl to fetch it. 2:6 When she opened it, she saw that it was a child, a boy crying. She took pity on it and said, “This must be a Hebrew child.”

Rashi here explicitly notes that this verse has a disconnected phrase, since in biblical Hebrew one washes in bodies of water (ב-)[11] not on (על) them:

רש"י שמות ב:ה "לרחץ על היאר" – סרס המקרא ודרשהו: ותרד בת פרעה על היאר לרחץ בו.

Rashi Exod 2:5 “to bathe in the Nile”—the verse is jumbled and should be understood as “the daughter of Pharaoh descended upon the Nile to wash in it.”

Rashi solves the problem, correctly indicating the plain meaning of the verse by its rearrangement. And yet, as is his way, he does not discuss why the verse was written in this unusual order. I suggest that making use of the term לרחץ על היאר (to wash upon the Nile) allows for a secondary meaning that describes Pharaoh’s daughter’s descent to the Nile as reflecting a (subconscious?) desire to cleanse herself concerning the Nile, as another common meaning of the word על is “concerning” or “on account of.”

Commenting on this verse, Midrash Tanhuma (Shemot §7) suggests that Pharaoh’s daughter washing in/at the river is a spiritual cleansing, שירדה לרחץ מגלולי בית אביה, “she went down to wash away her father’s idolatry.” According to R. Chanokh ben Yosef Zundel (d. 1867), the midrash is indeed picking up on the alternative meaning of this word:

עץ יוסף על מדרש תנחומא, פרשת שמות ז ולפי זה על היאור פי[רושו] בשביל היאור שהיא היראה של מצרים, כן הוא בילקוט ראובני

Etz Yosef, Midrash Tanchuma Shemot §7 According to this, “on the Nile” means “on account of the Nile,” which is venerated by the Egyptians. Thus can be found in Yalkut Reuveni.[12]

The midrash sees the symbolism as cleansing from her father's idolatry (the Nile), and thus an immersion prototypical of conversion. Nevertheless, I think that there is a more persuasive reason that follows the storyline and better explains why she wishes to cleanse herself.

As noted, just a few verses earlier, her father, the Pharaoh, commanded that infant male Hebrews be drowned in the Nile, and she is now about to reverse the process by drawing a Hebrew baby out of the Nile to save him. In fact, her reaction, “This must be a Hebrew child,” implies that her compassion is not only undeterred by her surmise concerning his origin, but on the contrary, it is an integral part of what motivates her rescue and her subsequent adoption of Moses. Indeed, her reaction indicates that she already has the inclination to rectify the royal decree and atone for her father’s crimes.[13]

The story does not begin with the fortuitous coincidence of the floating basket and the bathing princess, but with the natural feelings of guilt and horror of a sensitive daughter at the murderous policy of her despotic father. It continues with a descent to the Nile in which Hebrew children are drowned by her father’s decree, where she hopes לִרְחֹץ עַל הַיְאֹר to cleanse herself concerning the Nile.

Understood in this way, the subsequent verses (6–10) are an inevitable development of both divine providence and human response to guilt: Moses is saved and Pharaoh’s daughter is redeemed. The Nile’s waters, bloody from the countless murdered Hebrew infants, can hardly cleanse, but they do become the source of both rescue and catharsis. The underlying motivations that inform the narrative are subtly and artistically indicated through the intentional use of syntactical inversion.

Mikra Mesuras and Literary Sensitivity

Different languages demonstrate varying levels of syntactical tolerance and flexibility. In a typical introduction to one of Sherlock Holmes’ inimitable exploits (“A Scandal in Bohemia”), Holmes receives a note from a stranger seeking his help that concludes with “this account of you we have from all quarters received.” Holmes is able to determine detailed background regarding the stranger from examining the note, including his Germanic origin for, “A Frenchman or Russian could not have written that. It is the German who is so uncourteous to his verbs.”

In biblical Hebrew, as in modern Hebrew, syntax is quite tolerant of many arrangements and sequences of the various parts of speech. Yet, as we’ve seen, particular verses stretch the elasticity of biblical Hebrew beyond what is acceptable as normative biblical style. In some instances, the jumbled word order in a verse suggests an affront to logic.

The texts discussed above are just a few examples of mikra mesuras or anastrophe. The key to a deeper understanding of this literary phenomenon is not merely figuring out the meaning of the verse when reconstituted properly, but what the text is telling us by choosing to write it in an unconventional order in the first place.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

January 29, 2026

|

Last Updated

January 30, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Rabbi Shmuel Klitsner has taught Bible and Talmud for many years at Jerusalem’s Midreshet Lindenbaum. He is the chairman of Midreshet Lindenbaum’s groundbreaking Women’s Institute of Halakhic Leadership. Klitsner was involved in the award winning Hanukah animation Lights, and served as Rav of the School for Torah and Arts. Klitsner is the author of Wrestling Jacob: Deception, Identity, and Freudian Slips in Genesis and co-author of the educational novel, The Lost Children of Tarshish.

Essays on Related Topics: