Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Nile: The River that Sustained Egypt and Shaped Its Faith

Boat on the river Nile looking towards the pyramids (colorized), Louis Haghe after David Roberts, 1846.

Herodotus (5th cent. B.C.E.), the “father of history,” was not always the most accurate scholar.[1] In his depictions of nature, for instance, he claimed that lion cubs clawed their way out of the womb and that some tribes of men were dog-headed while others had no heads at all. That said, he was correct about the importance of the Nile in making Egypt uniquely fertile:

Herodotus History 2:5 For it would be clear to anyone of sense who used his eyes, even if there were no such information, that the Egypt to which the Greeks sail is land that has been given to the Egyptians as an addition and as a gift of the river.[2]

The Nile was the life source of Egypt, without which the ancient Egyptian civilization would not have existed. Its annual flooding and receding ensured Egypt’s agricultural prosperity regardless of weather patterns elsewhere in the Mediterranean. Nevertheless, deviations from the expected flood level did occur on occasion and this could wreak havoc.

When the river flooded too much or too little, it often led to food shortages and, at times, even political fragmentation. To anticipate such crises, the ancient Egyptians used Nilometers to measure the river’s water levels and predict the scale of the inundation.

The Biblical Attitude Towards the Nile

The ability of the Nile to provide Egypt with water and fertility, irrespective of local weather patterns, explains why the Bible says that Abram heads to Egypt in time of famine:[3]

בראשית יב:י וַיְהִי רָעָב בָּאָרֶץ וַיֵּרֶד אַבְרָם מִצְרַיְמָה לָגוּר שָׁם כִּי כָבֵד הָרָעָב בָּאָרֶץ.

Gen 12:10 There was a famine in the land, and Abram went down to Egypt to sojourn there, for the famine was severe in the land.[4]

In the Joseph story, Pharaoh imagines bounty and then ruin coming to Egypt in a dream, set upon the Nile:

בראשית מא:א ...וּפַרְעֹה חֹלֵם וְהִנֵּה עֹמֵד עַל הַיְאֹר. מא:ב וְהִנֵּה מִן הַיְאֹר עֹלֹת שֶׁבַע פָּרוֹת יְפוֹת מַרְאֶה וּבְרִיאֹת בָּשָׂר וַתִּרְעֶינָה בָּאָחוּ. מא:ג וְהִנֵּה שֶׁבַע פָּרוֹת אֲחֵרוֹת עֹלוֹת אַחֲרֵיהֶן מִן הַיְאֹר רָעוֹת מַרְאֶה וְדַקּוֹת בָּשָׂר וַתַּעֲמֹדְנָה אֵצֶל הַפָּרוֹת עַל שְׂפַת הַיְאֹר.

Gen 41:1 …Pharaoh dreamed that he was standing by the Nile, 41:2 and there came up out of the Nile seven sleek and fat cows, and they grazed in the reed grass. 41:3 Then seven other cows, ugly and thin, came up out of the Nile after them and stood by the other cows on the bank of the Nile.[5]

Similarly, the plagues against Egypt begin with an attack upon the Nile (Hebrew Yeʾor), repeating the name endlessly:

שמות ז:כ ...וַיַּךְ אֶת הַמַּיִם אֲשֶׁר בַּיְאֹר לְעֵינֵי פַרְעֹה וּלְעֵינֵי עֲבָדָיו וַיֵּהָפְכוּ כָּל הַמַּיִם אֲשֶׁר בַּיְאֹר לְדָם. ז:כא וְהַדָּגָה אֲשֶׁר בַּיְאֹר מֵתָה וַיִּבְאַשׁ הַיְאֹר וְלֹא יָכְלוּ מִצְרַיִם לִשְׁתּוֹת מַיִם מִן הַיְאֹר... ז:כד וַיַּחְפְּרוּ כָל מִצְרַיִם סְבִיבֹת הַיְאֹר מַיִם לִשְׁתּוֹת כִּי לֹא יָכְלוּ לִשְׁתֹּת מִמֵּימֵי הַיְאֹר.

Exod 7:20 … He struck the water in the Nile; all the water in the Nile was turned into blood, 7:21 and the fish in the Nile died. The Nile stank so that the Egyptians could not drink water from the Nile… 7:24 And all the Egyptians had to dig along the Nile for water to drink, for they could not drink the water of the Nile.

The second plague also begins with the Nile, as God explains to Moses (Exod 7:28), וְשָׁרַץ הַיְאֹר צְפַרְדְּעִים “the Nile will swarm with frogs.” While the plagues continue by destroying other aspects of Egypt’s economy, YHWH deliberately hits the Nile first.

Ezekiel envisions Pharaoh claiming to be the creator of the Nile, and prophesies that YHWH will catch Pharaoh like a fish out of the Nile and cast him on the desert sands:

יחזקאל כט:ג ...כֹּה אָמַר אֲדֹנָי יְ־הוִה הִנְנִי עָלֶיךָ פַּרְעֹה מֶלֶךְ מִצְרַיִם הַתַּנִּים הַגָּדוֹל הָרֹבֵץ בְּתוֹךְ יְאֹרָיו אֲשֶׁר אָמַר לִי יְאֹרִי וַאֲנִי עֲשִׂיתִנִי. כט:ד וְנָתַתִּי (חחיים) [חַחִים] בִּלְחָיֶיךָ וְהִדְבַּקְתִּי דְגַת יְאֹרֶיךָ בְּקַשְׂקְשֹׂתֶיךָ וְהַעֲלִיתִיךָ מִתּוֹךְ יְאֹרֶיךָ וְאֵת כָּל דְּגַת יְאֹרֶיךָ בְּקַשְׂקְשֹׂתֶיךָ תִּדְבָּק. כט:ה וּנְטַשְׁתִּיךָ הַמִּדְבָּרָה אוֹתְךָ וְאֵת כָּל דְּגַת יְאֹרֶיךָ עַל פְּנֵי הַשָּׂדֶה תִּפּוֹל לֹא תֵאָסֵף וְלֹא תִקָּבֵץ לְחַיַּת הָאָרֶץ וּלְעוֹף הַשָּׁמַיִם נְתַתִּיךָ לְאָכְלָה.

Ezek 29:3 … Thus said the Lord YHWH: I am going to deal with you, O Pharaoh king of Egypt, mighty monster, sprawling in your channels (lit. “Niles”),[6] who said, ‘My Nile is my own; I made it for myself.’ 29:4 I will put hooks in your jaws and make the fish of your channels cling to your scales; I will haul you up from your channels, with all the fish of your channels clinging to your scales. 29:5 And I will fling you into the desert, with all the fish of your channels, you shall be left lying in the open, ungathered and unburied…”

Similarly, when rebuking the Assyrian King Sennacherib, Isaiah imagines him boasting that he dried the Nile as a way of claiming to have conquered Egypt:

מלכים ב יט:כד אֲנִי קַרְתִּי וְשָׁתִיתִי מַיִם זָרִים וְאַחְרִב בְּכַף פְּעָמַי כֹּל יְאֹרֵי מָצוֹר.

2 Kgs 19:24 It is I who have drawn and drunk the waters of strangers; I have dried up with the soles of my feet all the streams of Egypt.

Thus, we see the central role that the Nile and its various streams and channels played for ancient Egypt in the eyes of the biblical authors.

Israel’s Rain versus Egypt’s River

Agriculture was relatively easy in the Nile Valley since the rich silt deposits brought in Egypt through the river created fertile topsoil each year, giving rise to successful yields. Deuteronomy makes a virtue of Israel’s lack of such a river: In contrast to Egypt, where the flooding brings the water and fertile soil into the canals and right up to the agricultural plots, the Israelites are blessed to rely on YHWH’s bounty through rainfall:

דברים יא:י כִּי הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר אַתָּה בָא שָׁמָּה לְרִשְׁתָּהּ לֹא כְאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם הִוא אֲשֶׁר יְצָאתֶם מִשָּׁם אֲשֶׁר תִּזְרַע אֶת זַרְעֲךָ וְהִשְׁקִיתָ בְרַגְלְךָ כְּגַן הַיָּרָק. יא:יא וְהָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר אַתֶּם עֹבְרִים שָׁמָּה לְרִשְׁתָּהּ אֶרֶץ הָרִים וּבְקָעֹת לִמְטַר הַשָּׁמַיִם תִּשְׁתֶּה מָּיִם.

Deut 11:10 For the land that you are about to enter to occupy is not like the land of Egypt, from which you have come, where you sow your seed and irrigate by foot like a vegetable garden. 11:11 But the land that you are crossing over to occupy is a land of hills and valleys, watered by rain from the sky.[7]

Of course, from the Egyptian perspective, the flooding was so beneficial that it could only be explained as a gift from the gods, a pattern of life to be worshipped as it brought about bounty and sustenance.

Why Is the Nile Different?

For the scientifically minded Greeks, the flooding was an enigma. Already Herodotus asked about it when he visited Egypt:[8]

Herodotus History 2:19 Neither from the priests nor from anyone else was I able to learn about the nature (phusius) of this river, and I was exceedingly anxious to learn why it is that the Nile comes down with a rising flood for one hundred days, beginning from the summer solstice again.

I was not able to find out anything at all about this from the Egyptians, despite my inquiries of them, as to what peculiar property the Nile possesses that is the opposite of every other river in the world.

Herodotus goes on to suggest various possibilities that Greek thinkers at the time were proposing: that it comes from wind, or the ocean, or melting snows farther south in Africa. The enigma remained unsolved until the 19th century, when it was determined that the flooding, which brought silt composed of rich topsoil to the surrounding areas, was a result of monsoon rains from the Indian Ocean falling on the Ethiopian highlands in the summer.

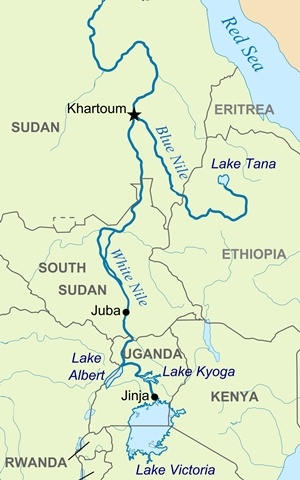

These waters then run into tributaries, primarily the White Nile, Blue Nile, and Atbara, bringing most of Egypt’s water supply through this rain pattern. Flowing from the Ethiopian highlands, these water sources meet and join in Khartoum, and their combined flow forms the Nile, the world’s largest river, stretching 4,238 miles from the area around Lake Victoria to the Mediterranean Sea.

In the northern part of Egypt, shortly before the Nile runs off into the Mediterranean Sea, it divides into multiple branches, called the Nile Delta, making a large swath of land in this region fertile. This is the region the Bible calls Goshen (etymology unknown), where Joseph settles his family (Gen 45:10, 47:1, 6, 27) and where the Israelites are living during their slavery (Exod 8:18, 9:26).

Egypt’s Three Seasons

Ancient Egypt had three seasons, roughly four months each, regulated by the Nile:

Akhet, “Inundation”—The first season of the year, began with the annual flooding of the Nile. This season was closely linked to the rising of the star Sirius (Sopdet), which typically occurred in mid-July. During this season, the floodplains of the river were inundated by water which created a fertile, dark black topsoil making agriculture in such an otherwise arid area not only possible but plentiful.

Peret, “Emergence”—When the water receded from the land, the fields were plowed and water channels were created to irrigate the crops. During this season the plants would emerge.

Shemu, “Harvest”—The plants would be allowed to grow until the harvesting season, which lasted from late spring until midsummer.

Egyptian New Year’s Festival

Each year, around mid-July, the ancient Egyptians celebrated the rise of the floodwaters, marking the start of their year in the festival of the Nile, during which the Egyptians would offer sacrifices, decorate their homes, and feast with entertainment and processions.

The Egyptian name for the Nile is Hapy, and they worshipped a god of this name, who personifies the Nile, the source of all life. , the god of fertility, is an androgynous, corpulent deity who sent blessings to the Egyptians yearly, with the Nile flooding. In honoring Hapy, the Egyptians would adorn their boats with flowers and flags and sail on the Nile to celebrate the life and abundance brought forth by the river, a divine blessing. This interaction of humans celebrating and providing offerings to Hapy was a way for the people to directly interact with the divine.

In temples across the country, rituals and offerings were given by the king to the deities, and as a semi-divine being himself, the king is ideologically the intermediary between the people and their gods. The king would also receive a ritual bath in Nile water for purification and bathing purposes.

In ancient Egypt, people likely bathed in the Nile for practical hygiene, like what the Bible describes regarding pharaoh’s daughter when she discovers Moses:

שמות ב:ה וַתֵּרֶד בַּת פַּרְעֹה לִרְחֹץ עַל הַיְאֹר וְנַעֲרֹתֶיהָ הֹלְכֹת עַל יַד הַיְאֹר...

Exod 2:5 The daughter of Pharaoh came down to bathe in the Nile, while her maidens walked along the Nile…

But the river also held deep ritual significance. For the pharaoh, ritual purification with Nile water was a formalized religious act performed at temple entrances by priests. This purification removed defilement and conferred regeneration, life (ankh), and prosperity (was), symbolically linking the king to the creative and renewing powers of the Nile flood and the primordial waters of Nun.[9]

Whether envisioning a ritual purification or a simple bathing, YHWH tells Moses when introducing the plague of blood that Pharaoh himself will be heading to the Nile waters in the morning:

שמות ז:טו לֵךְ אֶל פַּרְעֹה בַּבֹּקֶר הִנֵּה יֹצֵא הַמַּיְמָה וְנִצַּבְתָּ לִקְרָאתוֹ עַל שְׂפַת הַיְאֹר...

Exod 7:15 Go to Pharaoh in the morning, as he is coming out to the water, and station yourself before him at the edge of the Nile…[10]

The priests generally acted as a stand-in for the pharaoh in these rituals. It was their role to monitor and give blessings to the Nile, often through incense, flowers, and food.

Orienting Egyptian Geographical Worldview

As the main physical feature defining Egypt, the Nile River also shaped the Egyptian geographical understanding of their world in several ways.

South-North Orientation—When we think of maps, we envision north on top. For ancient Egyptians, however, it was the opposite, since the Nile enters Egypt from the south, and flows to the Mediterranean Sea in the north.[11]

Upper and Lower Egypt—The kingdom of ancient Egypt was divided in two, corresponding to a shift in the way the waters of the Nile flow. Lower Egypt corresponds to the northern part of the river, from the first cataract to the delta. A cataract is a section of the river where shallow, rocky rapids make navigation difficult; such cataracts characterize the southern stretch of the Nile, which corresponds to Upper Egypt.

When cursing the Assyrians, Nahum uses the imagery of the Egyptian southern capital, Thebes, surrounded by water and feeling safe, as an object lesson:

נחום ג:ח הֲתֵיטְבִי מִנֹּא אָמוֹן הַיֹּשְׁבָה בַּיְאֹרִים מַיִם סָבִיב לָהּ אֲשֶׁר חֵיל יָם מִיָּם חוֹמָתָהּ.

Nah 3:8 Were you any better than No-amon (the City of Amun, i.e., Thebes), which sits in the Nile’s channels, surrounded by water—its rampart a river, its wall consisting of sea?

Nahum’s point is that just as Thebes was conquered by its enemies (the Assyrians), despite its strategic location, so too will Assyria someday be defeated by its enemies.

Nekhbet and Wadjet, Vulture and —This division of lands played an important role in royal ideology. The Egyptian king was ruler of both Upper and Lower Egypt, and had separate titles, crowns, and protective deities representing these two lands. Nekhbet was a vulture goddess of Upper Egypt and Wadjet was the cobra goddess who embodied Lower Egypt. Temple architecture was even oriented and decorated with symbolism uniting these two lands under the rule of the pharaoh.

East-West, Living and Dead—The Nile River also delineated the land into East and West. For the Egyptians, the east, the land where the sun rises, was the land of the living. The west, where the sun sets, was the land of the dead. As a result, most mortuary architecture and cemeteries are on the west bank of the Nile while non-mortuary temples and cities were largely on the east side of the Nile.[12]

The Nile as Order within Chaos

To the ancient Egyptians, the universe functioned as a struggle of opposing forces. The Nile River, existing as it does in an otherwise hostile desert, helped reify this idea. Instead of good vs. evil, the ancient Egyptians saw their existence through the lens of order (maʿat) versus chaos (isfet), the fertile black lands (kemet) versus the sterile red lands (desheret) of the desert, life versus death.[13] The Nile itself embodied the positive elements of nature that were nurtured through ritual and religion.

In addition to Hapy’s role as the divine manifestation of the Nile, discussed above, the Egyptians connected other deities to this river:

Atum Forms the Benben Mound in the Watery Abyss—The creation story from Heliopolis (Iunu, biblical אוֹן ʾŌn)[14] begins with Nun, the primordial waters from which the world arose. In the story, a pyramidal mound (benben) of earth emerged from the waters, from which Atum, the creator god sprang. This god then ushered forth his children, Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture), either by sneezing, spitting, or self-pleasure, and they in turn give birth to Geb (earth) and Nut (sky), who in turn create the gods, leading to the formation of the universe as the Egyptians knew it.

This image of a watery abyss followed by a mound of earth as representing the creation of the world was based on the cycle of the yearly Nile flood; the imagery evoked the inundation and how pieces of land would look once the waters receded each year.

Osiris Legend—The river also plays a vital role in the myth of Osiris, the ancient Egyptian god of death and resurrection. In this story, the body of Osiris is chopped into pieces and thrown into the river. Isis, his wife/sister, gathers the pieces back together, bringing him back to life. As the god of the afterlife and fertility, Osiris was thus associated with the annual flood, which created new plant life.

Tears of Isis—The water in the Nile was further believed to be the tears of Isis, mourning her husband and/or the semen of Osiris which gave rise to new life.

Maʿat—The life-giving Nile waters were associated with the goddess Ma’at, who represented truth, harmony, and balance.

Khnum—In later dynasties, the Nile was also associated with the ram-headed god Khnum, lord of the water and god of rebirth.

Contemporary Celebrations: Sham el-Nessim and the Putrid Fesikh Fish

Even though modern Egyptians no longer worship Hapy or other Egyptian gods, they continue to observe traditions rooted in Pharaonic times. One such celebration is Sham el-Nessim, a festival marking the arrival of spring that has been celebrated for thousands of years, though its religious associations have faded. Some scholars suggest that the name Sham el-Nessim may be derived from Shemu (“harvest season”), while others note that the modern Arabic name means “smelling the breeze.”

This may be a reference to fesikh, the festival’s most infamous traditional food—a fermented and salted mullet fish known for its particularly odious smell, which, to this day, Egyptians enjoy during this period on picnics near the banks of the Nile with other traditional foods. The preparation of fesikh is also an ancient tradition, originating from the Egyptian practice of preserving fish through drying and salting. If improperly prepared, however, fesikh can cause botulism poisoning, which has occasionally led to illness and even death.

Modern Nile Celebrations Despite the End of the Flooding Cycle

The natural flooding cycle of the Nile was disrupted in the 1960s with the construction of the Aswan High Dam, which now regulates the river’s flow. While this has allowed for greater control over agriculture and water distribution, it has also severed the natural rhythm that sustained Egypt for millennia.

Even so, Egyptians continue to honor the Nile river’s role in agriculture and fertility through festivals like Wafaa El-Nil, Arabic for “Fidelity of the Nile.” This two-week festival begins on August 15 and commemorates the annual flooding of the river—once the lifeblood of ancient Egyptian civilization. People gather along the banks for music, dancing, and traditional food, echoing the age-old reverence for the river that made Egypt flourish.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

August 11, 2025

|

Last Updated

January 7, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Flora Brooke Anthony is an Egyptologist and Subject Matter Expert featured on the History Channel and the Discovery Channel. She earned her Ph.D. in Art History from Emory University and holds a master’s from the Institute of Egyptian Art and Archaeology at the University of Memphis. Flora is the author of Foreigners in Ancient Egypt: Theban Tomb Paintings from the Early Eighteenth Dynasty (2016). She currently serves as Director of Grants at the Academic Torah Institute - TheTorah.com.

Essays on Related Topics: