Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Neglected from Birth to Adolescence, Jerusalem Struggles to Love YHWH

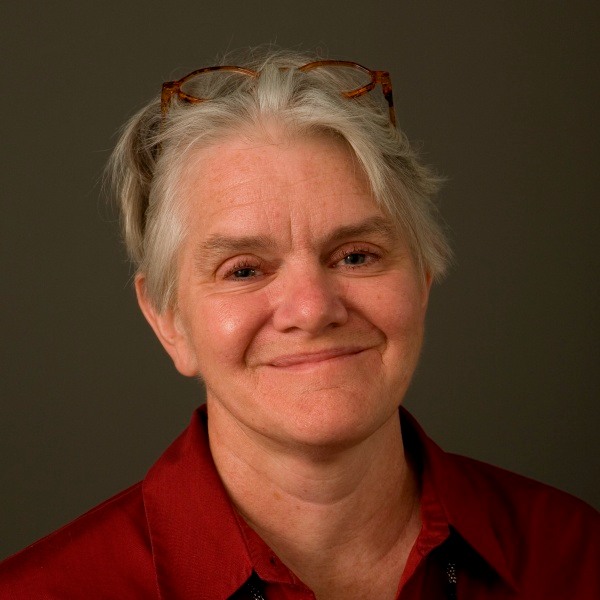

Ariadne Abandoned by Theseus, Angelica Kauffman, 1774. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston / Wikimedia

The prophet Ezekiel, speaking for the “Lord YHWH,” or אֲדֹנָי יְ־הוִה (v. 3),[1] explains why Jerusalem suffered from a decade or so of devastating attacks at the hands of the Babylonian Empire (Ezek 16). In 586 B.C.E., the Babylonians almost completely destroyed the city and its great Solomonic temple.

According to Ezekiel’s account, the city was punished by God because its people failed to maintain their covenant with the deity and its requirement that they give fidelity to YHWH alone. Instead, Jerusalem entered into alliances with other nations. In response, God is said to have been filled with burning anger or rage (חֵמָה; vv. 38, 42) and sends the Babylonians and their overpowering army against Jerusalem to destroy it.

Yet while this trope—God responds to covenant violations by sending enemy forces to inflict punishment on Israel or some subset thereof—is a familiar one in the Bible, Ezekiel’s text is hard for many readers to take because of the metaphor Ezekiel employs to describe Jerusalem’s infidelity. The city is gendered as female,[2] and her covenant with YHWH is depicted as a marriage.

Jerusalem, that is, is metaphorically depicted as YHWH’s wife, and so the wrathful anger that God visits on her for her “adulterous” relationships with other nations—however justified it may be from Ezekiel’s point of view—is for some all too reminiscent of the dangerous verbal and physical assaults that wives who are victims of spousal abuse suffer at the hands of enraged husbands.

Jerusalem’s Birth

Motifs of abuse also appear in the verses of Ezekiel 16 that lead up to the account of YHWH and Jerusalem’s marriage. These verses chronicle the story of the girl child Jerusalem from her birth to her coming into physical maturity.

As Ezekiel tells it, the young Jerusalem—in anticipation of the reviled identity that will characterize her as an adult—was deemed גֹעַל, “loathsome” or “abhorrent,” already on the day she was born (v. 5). Thus, the various practices that Ezekiel implies were normally enacted at a baby’s birth—even practices as basic as cutting the umbilical cord—were not undertaken on the newborn city’s behalf:

יחזקאל טז:ד וּמוֹלְדוֹתַיִךְ בְּיוֹם הוּלֶּדֶת אֹתָךְ לֹא כָרַּת שָׁרֵּךְ וּבְמַיִם לֹא רֻחַצְתְּ לְמִשְׁעִי וְהָמְלֵחַ לֹא הֻמְלַחַתְּ וְהָחְתֵּל לֹא חֻתָּלְתְּ.

Ezek 16:4 As for your birth, on the day you were born your navel cord was not cut, nor were you bathed in water to cleanse you (?);[3] you were not rubbed with salt, nor were you swaddled.

This passage about infant neglect can again be hard for many to read. Still, the verse provides insight into childbirth practices that may have been routinely performed in ancient Israel.

Salting and Swaddling

Ezekiel tells us that in addition to the cutting of the umbilical cord, the newborn Jerusalem, had she experienced a more typical birth, would have been rubbed with salt after delivery and swaddled. According to some interpreters, salt was rubbed on a neonate due to its hygienic and/or antiseptic properties,[4] while swaddling cloths wrapped around the baby reduced the amount of energy the child required to maintain its body temperature and other aspects of its physical well-being.[5]

Alternatively, Marten Stol (Free University, Amsterdam) proposes that salt was thought to help harden a newborn’s skin and cloth wrappings were similarly understood to give form to a newly delivered child.[6] Other scholars, however, consider the rubbing with salt to be primarily (or even exclusively) of ritual significance: either a protective rite to ward off evils that might threaten the child,[7] or, more likely, a ritual of purification.[8]

Indeed, salt is used as a purificatory agent elsewhere in the book of Ezekiel, where God commands that salt is to be thrown on two burnt offerings as part of the ritual that purifies the altar of the rebuilt Jerusalem temple that Ezekiel envisions:

יחזקאל מג:כד וְהִקְרַבְתָּם לִפְנֵי יְ־הוָה וְהִשְׁלִיכוּ הַכֹּהֲנִים עֲלֵיהֶם מֶלַח וְהֶעֱלוּ אוֹתָם עֹלָה לַי־הוָה.

Ezek 43:24 You shall present them [the burnt offerings] before YHWH, and the priests shall throw salt on them and offer them up as a burnt offering to YHWH.

The prophet Elisha also throws salt into a spring, when the men of Jericho tell him that its waters are foul, to remove the evils that contaminate it:

מלכים ב ב:כ וַיֹּאמֶר קְחוּ לִי צְלֹחִית חֲדָשָׁה וְשִׂימוּ שָׁם מֶלַח וַיִּקְחוּ אֵלָיו. ב:כא וַיֵּצֵא אֶל מוֹצָא הַמַּיִם וַיַּשְׁלֶךְ שָׁם מֶלַח וַיֹּאמֶר כֹּה אָמַר יְ־הוָה רִפִּאתִי לַמַּיִם הָאֵלֶּה לֹא יִהְיֶה מִשָּׁם עוֹד מָוֶת וּמְשַׁכָּלֶת.

2 Kgs 2:20 He [Elisha] said, “Bring me a new bowl and put salt in it.” They [the men of Jericho] brought it to him. 2:21 And he went to the spring and threw in the salt, and he said, “Thus said YHWH: I have healed these waters; from now on, neither death nor miscarriage will come from them.”

Because the spring’s noxious waters are said to be causing the land roundabout to suffer from מְשַׁכָּלֶת, “miscarriage,” the text suggests, at least metaphorically, that the Israelites associated salt’s purificatory properties with healthy childbearing.

Newborns’ Impurity

But why would baby Jerusalem (or any neonate) need purifying? The answer may lie in the post-partum legislation in Leviticus (12:1–8), which was authored by the so-called Priestly authors of the Bible, with whom the prophet Ezekiel had close affinities.[9] This passage describes how a mother is considered impure after she has given birth:

ויקרא יב:ב דַּבֵּר אֶל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל לֵאמֹר אִשָּׁה כִּי תַזְרִיעַ וְיָלְדָה זָכָר וְטָמְאָה שִׁבְעַת יָמִים כִּימֵי נִדַּת דְּוֹתָהּ תִּטְמָא.

Lev 12:2 Speak to the Israelites, saying: If a woman conceives and bears a male child, she shall be impure seven days; as at the time of her menstrual period, she will be impure.[10]

Commentators disagree on how, exactly, to interpret this verse, but I take it to mean that just as a menstruant’s impurity is contagious (Lev 15:19–24), so is the newly delivered mother’s impurity.[11] More specifically, anyone who touches a menstruating woman or touches anything on which she had sat or lain is also rendered impure, at least for that day (עַד הָעָרֶב, “until the evening,” vv. 19, 21–23). Analogously, anyone who touches a menstruant-like impure mother or touches anything on which she had sat or lain—a cohort that would surely have included her newborn child—should be rendered impure for that day.

Rubbing a newborn with salt might be a ritual deployed in ancient Israel to help mitigate the impurities to which a newborn baby would have been exposed through its contact with its contagiously impure mother.

A Natal-Day Bath

Ezekiel implies that a baby was commonly bathed on the day of its birth: וּבְמַיִם לֹא רֻחַצְתְּ לְמִשְׁעִי, “nor were you bathed in water” (16:4). Typically, commentators suggest that this was done to cleanse the child of blood and other fluids excreted during the birthing process (see v. 6),[12] but a natal-day bath may also have removed the impurities that a child would have contracted through contact with its ritually impure mother.[13]

This would be consistent with the requirement in Leviticus that anyone who comes into contact with something on which a menstruant has sat or lain wash themselves as part of the process that removes his or her impurity (15:21).[14]

Jerusalem’s Coming of Age

Yet in Ezekiel’s account, the natal-day bathing, like the salting, the swaddling, and the cutting of the umbilical cord, is not performed on behalf of the newborn Jerusalem. Rather, she is “thrown out” into an open field or the steppe land (16:5).[15] There, she lays flailing in her birth blood until YHWH passes by and, in a twice-repeated dictum, exhorts the infant Jerusalem, “In your blood, live!”[16]

יחזקאל טז:ו וָאֶעֱבֹר עָלַיִךְ וָאֶרְאֵךְ מִתְבּוֹסֶסֶת בְּדָמָיִךְ וָאֹמַר לָךְ בְּדָמַיִךְ חֲיִי וָאֹמַר לָךְ בְּדָמַיִךְ חֲיִי.

Ezek 16:6 And I passed by you and saw you wallowing in your blood, I said to you: “In your blood, live!” I said to you: “In your blood, live!”

Ezekiel’s subsequent description of Jerusalem growing up and coming of age parallels (albeit slightly out of order) the bodily changes that mark the initial stages of biological puberty in females. First, breast tissue starts to develop; about six months later, pubic hair begins to appear; and then, roughly a year later, a young woman experiences a significant growth spurt:[17]

יחזקאל טז:ז רְבָבָה כְּצֶמַח הַשָּׂדֶה נְתַתִּיךְ וַתִּרְבִּי וַתִּגְדְּלִי וַתָּבֹאִי בַּעֲדִי עֲדָיִים שָׁדַיִם נָכֹנוּ וּשְׂעָרֵךְ צִמֵּחַ וְאַתְּ עֵרֹם וְעֶרְיָה.

Ezek 16:7 I [YHWH] set you to grow like a plant of the field, and you matured and grew up, and you developed the loveliest of adornments:[18] your breasts became firm, and your [pubic] hair[19] grew in, yet you were naked and bare.

Sexual Maturity at Age Twenty

In communities today in the industrialized world, the processes of female puberty typically begin somewhere between the ages of eight and thirteen,[20] especially among girls who are generally in good health and have access to high-quality nutrition.[21] For young women in ancient Israel and elsewhere in the ancient world, however, the onset of biological puberty would have occurred later—most likely during the middle or latter half of the teenage years—slowed by factors such as too little body fat and a significant amount of physical exercise and/or physical labor.[22]

Menstruation, moreover, begins only two years or so into puberty, [23] and among women in preindustrial societies, fertility manifests only a year or so after that.[24] We can estimate, therefore, that women in the ancient world would have fully matured, biologically speaking, only as they approached age twenty. This estimate is confirmed in several ancient sources, including the Bible.[25] For example, the description in Leviticus of the monetary amounts that are to be dedicated for individuals of various ages differentiates between those who are between:

- five and twenty years of age—or, in the reading adopted here, those who are biologically prepubescent and pubescent (27:5); and

- twenty and sixty years old—or, in the reading adopted here, those who have fully matured, biologically speaking, as adults (27:3–4).[26]

The Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle also suggest that women in classical Greece began to bear children at about age twenty.[27] Aristotle writes, for example, that “after the age of twenty-one women are fully ripe for child-bearing” (History of Animals VII.1.582a.27–29), and Plato opines that “for a woman...she should start to produce children for the state in her twentieth year and go on to her fortieth” (Republic V.460e.4–5).[28]

Jerusalem’s Betrothal

Ezekiel imagines Jerusalem’s marriage to YHWH to follow hard upon the heels of the city’s reaching sexual maturity, or her עֵת דֹּדִים, “age of love”:[29]

יחזקאל טז:ח וָאֶעֱבֹר עָלַיִךְ וָאֶרְאֵךְ וְהִנֵּה עִתֵּךְ עֵת דֹּדִים וָאֶפְרֹשׂ כְּנָפִי עָלַיִךְ וָאֲכַסֶּה עֶרְוָתֵךְ וָאֶשָּׁבַע לָךְ וָאָבוֹא בִבְרִית אֹתָךְ נְאֻם אֲדֹנָי יְ־הוִה וַתִּהְיִי לִי.

Ezek 16:8 I [YHWH] passed by you and looked at you, and you had reached the age of love. So I spread out my robe’s edge over you, and I covered your nakedness, and I pledged myself to you and entered into a covenant with you—thus says the Lord YHWH. And you became mine.

Spreading a cloak over a bride-to-be is a gesture we also see in the book of Ruth. There, Ruth, when she seeks to marry Boaz, asks him to spread his cloak over her:

רות ג:ט וַיֹּאמֶר מִי אָתּ וַתֹּאמֶר אָנֹכִי רוּת אֲמָתֶךָ וּפָרַשְׂתָּ כְנָפֶךָ עַל אֲמָתְךָ כִּי גֹאֵל אָתָּה.

Ruth 3:9 He [Boaz] said, “Who are you?” And she answered, “I am Ruth, your servant; spread your cloak over your servant, for you are [my] redeemer.”

Likewise, YHWH’s spreading the edge or skirt of the deity’s garment over Jerusalem indicates that the two have become formally betrothed.[30] Indeed, YHWH signals this by saying of Jerusalem at the end of the verse, וַתִּהְיִי לִי, “you became mine.”

Yet however joyful this scene of betrothal might seem, there is something deeply disquieting about it. YHWH’s covering of Jerusalem’s “nakedness” signals that Jerusalem has been unclothed for what our timeline suggests are the almost two decades between the time she was abandoned in the open field as an unswaddled foundling and her coming of age and into sexual maturity. Indeed, the doubled description of Jerusalem as both עֵרֹם, “naked,” and עֶרְיָה, “bare” (v. 7), may emphasize the exceedingly long duration of Jerusalem’s exposed state.[31]

Jerusalem Is Bathed

As this betrothal scene continues, YHWH says to Jerusalem:

יחזקאל טז:ט וָאֶרְחָצֵךְ בַּמַּיִם וָאֶשְׁטֹף דָּמַיִךְ מֵעָלָיִךְ וָאֲסֻכֵךְ בַּשָּׁמֶן.

Ezek 16:9 Then I bathed you with water, and I rinsed your blood from upon you.

But what blood is this? Some answer that it is the blood of Jerusalem’s recently begun menses.[32] But it seems unthinkable that Ezekiel, a priest whose ideology is closely aligned with that of the Bible’s Priestly writers and the related Holiness source, could envision YHWH rinsing off menstrual blood, which the Priestly and Holiness traditions unrelentingly categorize as impure.[33]

Instead, just as we are to imagine that the foundling Jerusalem was left unclothed from the time of her birth, Ezekiel implies that Jerusalem has been covered with the blood of childbirth throughout that same period of time.[34] After all, the bath YHWH gives Jerusalem at betrothal is the only bath that has been mentioned since Jerusalem was left unwashed on her natal day (v. 4).

Indeed, YHWH’s twice-repeated dictum that exhorts the newborn Jerusalem to “in your blood, live!” (v. 6) can be taken to parallel the twofold description of Jerusalem as both “naked” and “bare” (v. 7), underscoring the point that Jerusalem has remained terribly neglected—unclothed and bloodied—from her natal day until some twenty or so years later, when she finally comes into her maturity. YHWH, that is, although exhorting the foundling Jerusalem to “live” and so saving her from a sure death (v. 6), does nothing else throughout the long years of Jerusalem’s infancy, childhood, and pubescence to resolve her abject status.

The Upshot: Jerusalem as Girl Child and Married Woman

No matter how loving YHWH’s intent in clothing and bathing the newly matured Jerusalem on the occasion of their betrothal (vv. 8–9), such gestures of care can hardly overcome Jerusalem’s childhood experiences of abandonment and neglect (vv. 4–6).[35] It is thus no wonder, given what we know about cycles of abuse, that Jerusalem who has been unloved all her life, fails to engage lovingly and devotedly in her marriage.

Still, although reading Ezekiel 16’s accounts of abuse can be a challenge for many, one has to admit that Ezekiel proves himself to be notably accurate in his renderings of the female life cycle in ancient Israel, as well as the costs that girls and young women can suffer if they are not nurtured with the appropriate rituals and care at birth and as they grow up.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

January 2, 2026

|

Last Updated

February 7, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Susan Ackerman is Preston H. Kelsey Professor of Religion, Emerita, at Dartmouth College. She received a Masters of Theological Studies from Harvard Divinity School and a Ph.D. in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations from Harvard University. Her books include Maturity, Marriage, Motherhood, Mortality: Women’s Life-Cycle Rituals in Ancient Israel; Gods, Goddesses, and the Women Who Serve Them; Women and the Religion of Ancient Israel; and When Heroes Love: The Ambiguity of Eros in the Stories of Gilgamesh and David. She is the co-editor of Celebrate Her for the Fruit of Her Hands: Essays in Honor of Carol L. Meyers. She served on board of the W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem (2007–2013) and on the board of the American Society of Overseas Research formerly the American Schools of Oriental Research) from 2007–2024, including a six-year term as the organization’s president (2014–2019). She also served as the president of the New England and Eastern Canada Region of the Society of Biblical Literature (2013–2014).

Essays on Related Topics: