Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Owls Aren’t Kosher—But What Do They Symbolize?

Painted sycomore fig wood figure of a Ba-bird. 332 B.C.E or later. British Museum

Among the nineteen birds and one bat that Leviticus classifies as impure and unsuitable for eating are several species of owls:

ויקרא יא:יג וְאֶת אֵלֶּה תְּשַׁקְּצוּ מִן הָעוֹף לֹא יֵאָכְלוּ שֶׁקֶץ הֵם אֶת הַנֶּשֶׁר וְאֶת הַפֶּרֶס וְאֵת הָעָזְנִיָּה. יא:יד וְאֶת הַדָּאָה וְאֶת הָאַיָּה לְמִינָהּ. יא:טו אֵת כָּל עֹרֵב לְמִינוֹ. יא:טז וְאֵת בַּת הַיַּעֲנָה וְאֶת הַתַּחְמָס וְאֶת הַשָּׁחַף וְאֶת הַנֵּץ לְמִינֵהוּ. יא:יז וְאֶת הַכּוֹס וְאֶת הַשָּׁלָךְ וְאֶת הַיַּנְשׁוּף׃ יא:יח וְאֶת הַתִּנְשֶׁמֶת וְאֶת הַקָּאָת וְאֶת הָרָחָם. יא:יט וְאֵת הַחֲסִידָה הָאֲנָפָה לְמִינָהּ וְאֶת הַדּוּכִיפַת וְאֶת הָעֲטַלֵּף.

Lev 11:13 These you shall regard as detestable among the birds. They shall not be eaten; they are an abomination: the eagle, the vulture, the osprey, 11:14 the buzzard, the kite of any kind; 11:15 every raven of any kind; 11:16 the ostrich, the nighthawk, the sea gull, the hawk of any kind; 11:17 the little owl, the cormorant, the great owl, 11:18 the water hen, the desert owl, the carrion vulture, 11:19 the stork, the heron of any kind, the hoopoe, and the bat.[1]

The owl is not singled out, but is included among the many, mostly predatory, prohibited birds.

Owls in Ancient Egypt

A very early image of an owl is found already in the Libyan Palette, ca. 3200–3000 B.C.E., where it symbolizes a city (“Eagle-Owl City”) under attack.[2] Owls were also used in the Egyptian hieroglyphic system, where they potentially become linked with death via the use of the owl hieroglyph, representing the phoneme “M,”[3] as in the word MWT, “death”: ![]() .[4]

.[4]

In the funerary Pyramid Texts (3rd–2nd millennium B.C.E.), the meaning “decapitate” is expressed using either (1) the word HSQ, “decapitate” alongside the owl symbol (used as a determinative to identify the category of the word); or (2) an image of an owl chopped off by a knife.[5]

Mummified owls have been found in Egyptian tombs,[6] often decapitated and burnt prior to internment. These owls may have served as votive offerings for an Egyptian deity, though there are no known owl-deities in the Egyptian pantheon. Alternatively, their decapitation could have had a ritual significance, such as canceling an illness omen portended by seeing or hearing an owl.[7] Owl-shaped amulets discovered in the tombs of the Pharaohs may also have been used to protect the wearer from the dangers in the afterlife.[8]

Finally, the concept that an individual’s soul migrates after death was often depicted in the form of a human-headed bird, usually interpreted as a falcon.

Ornithologist Alan Sieradzki, however, suggests that the image may be an owl, which is known to roost in and around tombs:[9]

It does not take much imagination to consider the idea that glimpsed sightings of owls, with their anthropomorphic facial features, coming and going from these tombs at dusk or dawn, were mistakenly believed to be human headed birds and thus became the very basis of the ba-bird belief.[10]

Owls in Ancient Mesopotamia

In the city-lament The Curse of Agade (ca. 2000–1750 B.C.E.), which narrates a conflict between the king of Akkad, Naram-Sin (ca. 2254–2218 B.C.E.), and the gods that results in Akkad’s destruction, a curse invites the owl to inhabit the city’s gates:[11]

Curse of Agade, OB ll. 256–271 May foxes that frequent ruin mounds brush with their tails your fattening-pens (?), established for purification ceremonies! May the owl [ukuku-bird],[12] the bird of depression, make its nest in your gateways, established for the Land![13]

The joining of the fox and the owl, and their respective locations, indicates that both the cultic sphere and the judicial/civic sphere will become un-domesticated. The more fragmentary Lament for Eridug (ca. 2000 B.C.E) includes a similar example of the owl’s association with desolate places, referring to “the bird of destroyed cities…a nest. The owl [ukuku-bird], bird of heart’s sorrow” (ll. 81–82).[14]

Owls in the Bible

The association of owls with ruins and desolation is also found in Zephaniah’s oracle against Nineveh, the capital of Assyria, where owls are among the animals that will displace humans after the city is destroyed:[15]

צפניה ב:יג וְיֵט יָדוֹ עַל צָפוֹן וִיאַבֵּד אֶת אַשּׁוּר וְיָשֵׂם אֶת נִינְוֵה לִשְׁמָמָה צִיָּה כַּמִּדְבָּר.

Zeph 2:13 And he [YHWH] will stretch out His hand against the north and destroy Assyria, and He will make Nineveh a desolation, a dry waste like the desert.

ב:יד וְרָבְצוּ בְתוֹכָהּ עֲדָרִים כָּל חַיְתוֹ גוֹי גַּם קָאַת גַּם קִפֹּד בְּכַפְתֹּרֶיהָ יָלִינוּ קוֹל יְשׁוֹרֵר בַּחַלּוֹן חֹרֶב בַּסַּף כִּי אַרְזָה עֵרָה.

2:14 Herds shall lie down in it, every wild animal of the earth; the desert owl and the screech owl[16] shall lodge on its capitals; the owl shall hoot at the window, the raven croak on the threshold, for its cedar work will be laid bare.

Similarly, In Isaiah’s oracle against the Edomites, owls head the list of animals that will inhabit Edom after the complete demolition of the habitable and arable land:

ישׁעיה לד:יא וִירֵשׁוּהָ קָאַת וְקִפּוֹד וְיַנְשׁוֹף וְעֹרֵב יִשְׁכְּנוּ בָהּ וְנָטָה עָלֶיהָ קַו תֹהוּ וְאַבְנֵי בֹהוּ. לד:יב חֹרֶיהָ וְאֵין שָׁם מְלוּכָה יִקְרָאוּ וְכָל שָׂרֶיהָ יִהְיוּ אָפֶס.

Isaiah 34:11 But the desert owl and the screech owl[17] shall possess it; the great owl and the raven shall live in it. He shall stretch the line of confusion and the plummet of chaos over it. 34:12 They shall call its nobles No Kingdom There, and all its princes shall be nothing.

The owl will keep company not only with real animals—the jackel, the ostrich, the wildcat, and the hyena—but also with mythical creatures: the goat-demon and Lilith, a female demon:[18]

ישׁעיה לד:יג וְעָלְתָה אַרְמְנֹתֶיהָ סִירִים קִמּוֹשׂ וָחוֹחַ בְּמִבְצָרֶיהָ וְהָיְתָה נְוֵה תַנִּים חָצִיר לִבְנוֹת יַעֲנָה. לד:יד וּפָגְשׁוּ צִיִּים אֶת אִיִּים וְשָׂעִיר עַל רֵעֵהוּ יִקְרָא אַךְ שָׁם הִרְגִּיעָה לִּילִית וּמָצְאָה לָהּ מָנוֹחַ. לד:טו שָׁמָּה קִנְּנָה קִפּוֹז וַתְּמַלֵּט וּבָקְעָה וְדָגְרָה בְצִלָּהּ אַךְ שָׁם נִקְבְּצוּ דַיּוֹת אִשָּׁה רְעוּתָהּ.

Isaiah 34:13 Thorns shall grow over its strongholds, nettles and thistles in its fortresses. It shall be the haunt of jackals, an abode for ostriches.[19] 34:14 Wildcats shall meet with hyenas; goat-demons shall call to each other; there also Lilith shall repose and find a place to rest. 34:15 There shall the owl[20] nest and lay and hatch and brood in its shadow; there also the buzzards shall gather, each one with its mate.[21]

Isaiah declares that “God’s spirit” has called these creatures together and “apportioned” the territory to them, permanently transferring the land of Edom’s deed from human inhabitants to these creatures (vv. 16–17).[22]

According to sociologist Adrian Franklin:

Animals convey meanings that are culturally specific; in viewing animals, we cannot escape the cultural context in which that observation takes place. There can be no deep, primordial relationship underlying the zoological gaze since it must always be mediated by culture.[23]

Both Zephaniah and Isaiah imagine centers of power destroyed and returned to wilderness, and they populate that desolation with animals that, presumably, will turn away future potential inhabitants. The presence of the owl, and its associates, thus marks the transition of a space from human habitation to desolation.

The psalmist, bemoaning his suffering from a physical illness, plays on the themes of loneliness and isolation as well:

תהלים קב:ז דָּמִיתִי לִקְאַת מִדְבָּר הָיִיתִי כְּכוֹס חֳרָבוֹת.

Ps 102:7 [NRSVue 102:6] I am like a desert owl of the wilderness, like a little owl of the waste places.

Owls in the First Millennium Levant

For some of Israel’s neighbors, the owl was also apparently associated with desolation and death. For example, in the Aramaic Sefire Treaties (8th c. B.C.E., Syria), a curse invoked against the city of Arpad should they violate the treaty terms includes the owl, among other animals, as markers of ruins:[24]

ותהוי ארפד תל ל[רבק צי ו]צבי ושעל וארנב ושרן וצדה ו.. ועקה.

Stele I, face A, ll. 32–33 And may Arpad become a mound to [house the desert animal] and the gazelle, and the fox and the hare, and the wildcat and the owl and the [ ] and the magpie![25]

The Deir ʿAlla (Balaam) Inscription (ca. 800 B.C.E., Jordan) tells of a divine vision so terrible that it causes the prophet Balaam to weep. The text is fragmentary, making the function of the owl difficult to determine, but the initial list of animals suggests a reversal of the hierarchy of the created order (e.g., swift and crane insulting the eagle).[26]

כי ססעגר חרפת נשר וקס רחמן יענה חסד דרס בני נתץ וצרה

Deir Alla i.10 It shall be that the swift and crane will shriek insult to the eagle, and a nest of vultures shall cry out in response. The stork, the young of the falcon and the owl,

אפרחי אנפה דרד נשרת יון וצפר בני ארין וצץ פרח מן מטה באשר רחלן ייבל חטר ארנבן אכלו פחד חפשית שבעו לחם ונמלן רוו חמאה חמרן שתיו חמר וקבען

i.11 The chicks of the heron, sparrow and cluster of eagles; pigeons and birds, [and fowl in the s]ky. And a rod [shall flay the cat]tle; where there are ewes, a staff shall be brought. Hares – eat together! Free[ly feed], oh beasts [of the field]! And [freely] drink, asses and hyenas![27]

Balaam’s invitation to the beasts, asses, and hyenas to eat and drink suggests a parallel with YHWH granting the land of Edom to the wild creatures (Isa 34:17).

Finally, at the 8th century B.C.E. Phoenician cremation sites in the necropolis of al-Bass, on the coast of modern Lebanon, two owl claws were found among faunal remains that showed evidence of having been boiled or cooked. Philip Schmitz (Professor Emeritus, Eastern Michigan University) notes:

[The] excavator surmises that the remains of a meal or an offering had been placed on the funeral pyre together with the corpse of the deceased and subsequently mixed with the human remains in the burial urn.[28]

While it is unclear from the evidence whether the claws were part of a ritual meal or offering, their presence indicates that owls were significant to Phoenician afterlife beliefs. Schmitz speculates that the owl may have symbolized the desolation of the deceased or their survival in the afterlife, or it may have been used in a ritual to improve their experience in the afterlife.[29]

Owls in Context

There is something uncanny about owls, with their nocturnal nature and the haunting sound of their vocalizations.[30] Large, expressive eyes and the ability to rotate their head also make them stand out among birds. It’s no wonder, then, that owls have captured the imagination since at least the 4th millennium B.C.E.[31]

In the Bible, as elsewhere in ancient Near Eastern texts and iconography,[32] owls are rare, but when they do appear, they are generally desolation-coded, connected to depression, death, and de-populated places.[33] Their presence in the midst of an urban settlement marked the incursion of death and the underworld into the domesticated world of the living, thus communicating the order of the world turned upside down.

Postscript

The Queen of the Night Plaque

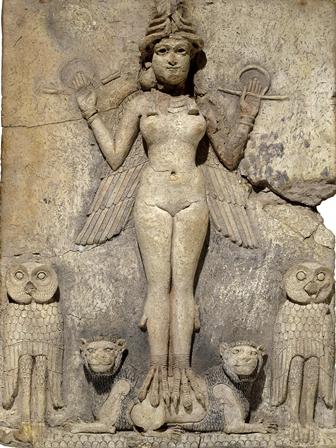

The nude female figure standing upon lions and flanked by owls in the Burney Relief (perhaps ca. 18th century B.C.E.; retitled the Queen of the Night Plaque) offers an intriguing set of associations for the owl in Mesopotamia. The work is unprovenanced and its authenticity has been questioned since it was first introduced to the public in 1936.[34]

There have been multiple theories about the identity of the female figure, her association with the lions and owls, and the possible reason for her nakedness.

Lilith – Archaeologist Henri Frankfort was the first to suggest an identification with Lilith.[35] He notes that the Sumerian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh includes a frament in which Gilgamesh cuts down a tree inhabited by Lilith: “In the midst Lilith had built a house, the shrieking maid, the joyful, the bright Queen of Heaven.” He suggests, based on the “shrieking” behavior and the fact that both the owl and Lilith are known for “nocturnal flight,” that the owl may have been Lilith’s symbol.[36]

Innana/Ishtar – Historian Thorkild Jakobsen notes that the bird claws in the image of the figure and the owls surrounding her suggests a divine figure with an “owl character,” and he argues that it represents one of the goddess Innana/Ishtar’s forms: “The Akkadian word for owl, eššebu corresponds to Sumerian ninna ‘owl’ and also to d nin-ninna ‘Divine lady owl,’ that is owl goddess. This owl goddess Nin-ninna, however, is Ishtar, the Akkadian name of Inanna.”[37]

Ereshkigal – Archaeologist Dominique Collon argues that the figure is a representation of Ereshkigal, the goddess of the underworld and sister of Innana/Ishtar, noting that in the “Descent of Innana” myth, as she travels to the underworld to visit her sister, all of Inanna’s finery, including her rod and ring, are taken from her and presumably end up in the possession of Ereshkigal:[38]

Descent of Innana From her body the royal robe was removed.

Inanna asked: “What is this?”

She was told: “Quiet, Inanna, the ways of the underworld are perfect. They may not be questioned.”

Naked and bowed low, Inanna entered the throne room.

Erishkigal rose from her throne. Inanna started toward the throne.

Then Erishkigal fastened on Inanna the eye of death. She spoke against her the word of wrath.[39]

The representation of the goddess as nude marks her sovereignty over the naked and the dead. The owls flanking her would communicate her status as ruler of the underworld who strips naked those who appear before her. All of these identifications, but particularly the association with Erishkigal, would mark the owl as a chthonic (underworld) image. It would have been seen as an avatar of the power of death, bringing silent death and desolation on its wings.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 14, 2025

|

Last Updated

February 9, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Phillip Michael Sherman is a Professor of Religion at Maryville College (Tennessee, USA). He holds a PhD in Hebrew Bible and Classical Jewish Hermeneutics from Emory University. He is the author of Babel’s Tower Translated: Genesis 11 and Ancient Jewish Interpretation (Brill, 2013). He has also published on animals in the Bible, including “Animals,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Law (Oxford University Press, 2015), and “The Hebrew Bible and the ‘Animal Turn’” in Currents in Biblical Research 19 (2020).

Essays on Related Topics: