Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Pharaoh’s Palace Lions Become Playful Dogs Before Moses

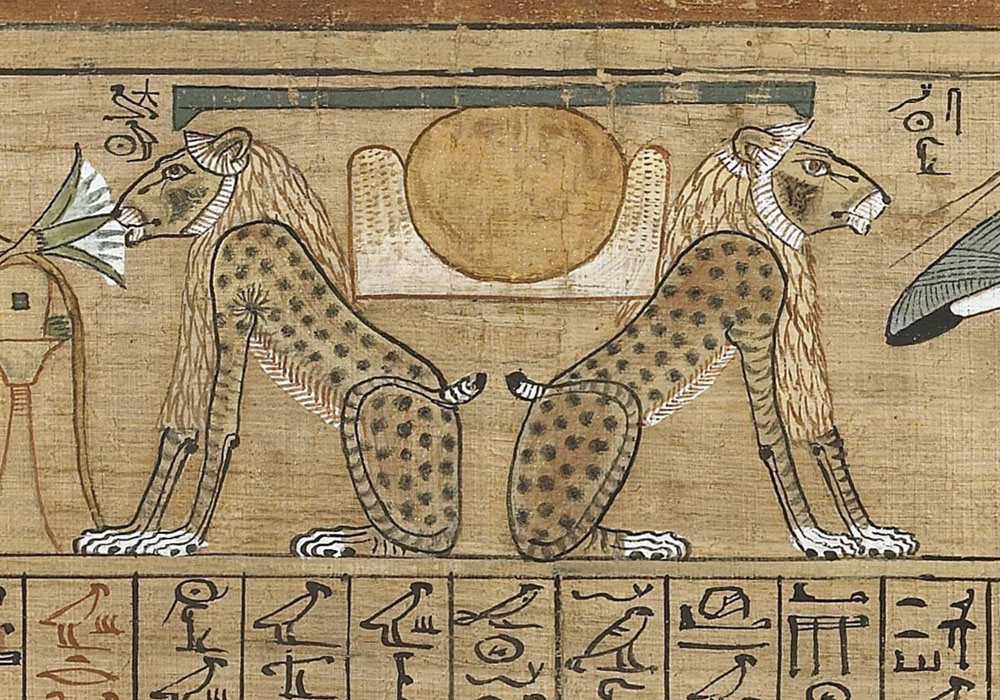

Lions depicted on the Book of the Dead of Ani papyrus, 19th Dynasty. British Museum

After speaking with the Israelites and informing them that YHWH will soon free them from bondage, Moses and Aaron go to speak with Pharaoh:

שמות ה:א וְאַחַר בָּאוּ מֹשֶׁה וְאַהֲרֹן וַיֹּאמְרוּ אֶל פַּרְעֹה כֹּה אָמַר יְ־הֹוָה אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל שַׁלַּח אֶת עַמִּי וְיָחֹגּוּ לִי בַּמִּדְבָּר.

Exod 5:1 Afterward Moses and Aaron went and said to Pharaoh, “Thus YHWH, the God of Israel: Let My people go that they may celebrate a festival for Me in the wilderness.”[1]

The Torah never explains how Moses and Aaron simply enter Pharaoh’s palace. This may be the inspiration behind a midrashic story whose earliest exemplar is found in דברי הימים של משה רבינו The Chronicle of Moses (10th/11th cent.),[2] a medieval text which retells the life of Moses, best known for its long depiction of Moses as the conqueror and ruler of Kush. At the point in the account in which Moses and Aaron first go to Pharaoh, it describes how they overcome lions who were guarding the palace gates:

דברי הימים של משה רבינו ואח"כ באו משה ואהרן למצרים ויבואו לבית פרעה.

Chronicle of Moses Afterwards, Moses and Aaron came to Egypt and went to the house of Pharaoh.[3]

והיו בשער בית פרעה שני כפירים שאין שום אדם יכול לקרב מפניהם לשער המלך מפחדם, שהיו טורפים למי שרואים אותו, עד שיבוא רועה הכפירים ויסירם ממנו.

And two young lions were near the gate to Pharaoh’s home. On their account, nobody could approach the king’s gate out of fear of them, for they would tear up anyone they saw, until the lion keeper would come and remove them.

ובעת ששמעו שבאו משה ואהרן התירו השומרים את הכפירים והניחום על פתח השער בעצת בלעם הקוסם וחרטומי מצרים.

When they heard that Moses and Aaron were coming, the guards released the lions and placed them at the entrance to the gates, at the advice of Balaam the diviner[4] and the Egyptian sorcerers.

ובבוא משה ואהרן לפתח השער ויט משה את מטהו על הכפירים והם שמחו לקראתו ויבואו אחריו והיו שוחקים לפניו כשחוק הכלבים על בעליהם בעת בואם מהשדה.

And when Moses and Aaron came to the entrance to the gate, Moses stretched out his staff[5] over the lions, and they were so happy at his approach that they came to him playfully, like dogs play with their masters when they come home from the field.

This, of course, shocks the Pharaoh and his palace officials, who were expecting the two men to have been torn to pieces:

ובעת שראו פרעה ועבדיו כך יראו מאד מפניהם ויאמרו להם "מה מעשיכם? ומה אתם רוצים?" ויאמרו "אלהי העברים נקרה אלינו לאמר לך 'שלח עמי ויעבדוני!" א"ל פרעה: "שובו לפני מחר ואשיבה לכם דבר." ויעשו כן ויצאו וילכו.

When Pharaoh and his servants saw this, they were terrified of them, and said to them: “What do you do? What do you want?” And they said: “The God of the Hebrews called out to us to say to you: ‘Send out my people so they can serve me!’”[6] Pharaoh said to them: “Come back tomorrow and I’ll answer you.” And they did so; they left and went [back to the Hebrews].

Pharaoh was stalling so he could turn to some of his trusted advisers, including Balaam:

אח"כ קרא פרעה לחכמים ולחרטומים ולמעוננים ולקוסמים וביניהם בלעם, ויאמר להם המלך: "כזאת וכזאת אמרו אלי הנביאים." ויאמר לו בלעם: "איך קרבו על השער ולא טרפו אותם הכפירים?"

Afterwards, Pharaoh called his sages, magicians, diviners, and sorcerers, among whom was Balaam, and the king said to them: “Such and such did those prophets say to me.” And Balaam said to him: “How did they get close to the gate without the lions tearing them up?”

א"ל פרעה: "כי באו ולא עשו בהם כלום, והיו משחקים עמם כאילו הם גדלום, ושמחו עמהם כשמחת הכלבים עם אדוניהם אשר גדלום מנעוריהם!" ויאמר בלעם: "אין אלו [כי אם][7] כמונו, ועתה שלח לקרוא אותם ונתווכח עמם יחדיו לפניך."

Pharaoh said to him: “For they came, and [the lions] did nothing to them, they just played with them as if they [Moses and Aaron] had raised them, and were frolicking with them like dogs do with the masters who raised them from their youth!” Balaam said: “These men are merely like us, now send for them, and we will dispute with them together before you.”

Whatever its origins, this story made it from the Chronicles of Moses into the Yalkut Shimoni, the 13th century midrash collection by R. Shimon of Frankfurt,[8] and the Sefer HaYashar, the 16th century retelling of the biblical stories from creation to Joshua.[9] It also appears in the medieval Liturgical Targum found mainly in mahzorim (festival prayerbooks), oddly, as part of its rendition of the Song of the Sea.

What Is a Targum?

Though the root ת.ר.ג.מ originally had various different meanings, including “to translate” or “to interpret,” over time, the noun targum (pl. targumim) came to exclusively refer to the group of Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Bible. We must distinguish between the practice of Targum, i.e., the live translation of Scripture in the synagogue, and the Targums, i.e., written texts which ultimately originated out of this practice, but are fundamentally the product of centuries of literary development that came afterwards.

The origins of Targum as a practice remain largely unknown. Some scholars have suggested that Hebrew literacy was dwindling among the Jewish population, and that a translation in the lingua franca of the time (Aramaic) was necessary to keep Scripture accessible. Others have argued that the sanctity of Scripture could be maintained by having the written Hebrew text read from a scroll and having the interpretative translation in Aramaic be performed orally.[10] Whatever the origin, somewhere in the first centuries C.E., oral Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Bible were being read in the synagogue in tandem with the Hebrew text.[11]

We have no direct, contemporary descriptions of how Targum was actually practiced in the early centuries and must therefore rely primarily on Rabbinic sources,[12] which, though invaluable, must be taken with a grain of salt; they more often reflect what ought to happen, rather than what actually happened. These statements are diverse in content, purpose, and provenance, and represent more than a thousand years of thought concerning targumic practice in both Palestinian and Babylonian contexts.

Our most valuable source with regard to the practice of Targum in its earliest context is in the Jerusalem Talmud, though we cannot be certain about its reliability. The main person, R. Samuel, was a fourth-century Palestinian Amora, and if the attribution is authentic, it would suggest that the practice of Targum was already a fixed tradition in some Jewish communities at this point in time:

ירושלמי מגילה ד:א רִבִּי שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר רַב יִצְחָק עָאַל לַכְּנִישְׁתָּא. חַד בַּר נַשׁ קָאִים מְתַרְגֵּם סְמִיךְ לָעֲמוּדָא. אֲמַר לֵיהּ: "אָסוּר לָךְ! כְּשֵׁם שֶׁנִּיתְנָה בְּאֵימָה וְיִרְאָה כָּךְ אָנוּ צְרִיכִין לִנְהוֹג בָּהּ בְּאֵימָה וְיִרְאָה."

y. Meg. 4:1 Rabbi Samuel bar Rav Isaac went to a synagogue. One man rose to translate while leaning on a pillar. [Rabbi Samuel] said to him, “This is forbidden! Just as [the Torah] was given in fear and awe, so too we must behave towards it with fear and awe.”

רִבִּי חַגַּי אָמַר: רִבִּי שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר רַב יִצְחָק עָאַל לַכְּנִישְׁתָּא. חֲמָא חוּנָה קָאִים מְתַרְגֵּם וְלָא מֵקִים בַּר נַשׁ תַּחְתּוֹי. אֲמַר לֵיהּ. אֲסִיר לָךְ. כְּשֵׁם שֶׁנִּיתְנָה עַל יְדֵי סִרְסוּר כָּךְ אָנוּ צְרִיכִין לִנְהוֹג בָּהּ עַל יְדֵי סִרְסוּר. עָאַל רִבִּי יוּדָה בַּר פָּזִי וְעָבְדָהּ שְׁאֵילָה (דברים ה:ה): "אָנֹכִי עוֹמֵד בֵּין יְי וּבֵינֵיכֶם בָּעֵת הַהִיא לְהַגִּיד לָכֶם אֶת דְּבַר יְי."[13]

Rabbi Ḥaggai relates: Rabbi Samuel bar Rav Isaac went to a synagogue. He saw Huna rise [to read the Torah] and translate [himself], without appointing another person [to read or translate] in his stead. He said to him: “This is forbidden! Just as [the Torah] was given by an agent (=Moses), so too we must present it (in translation) through an agent.” Rabbi Jehudah bar Pazi rose and supported this stance through a homiletical halakhic inquiry [on the verse] (Deut 5:5): “I stood between the LORD and you at that time to convey the LORD’s words to you.”

רִבִּי חַגַּיי אָמַר: רִבִּי שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר רַב יִצְחָק עָאַל לַכְּנִישְׁתָּא. חֲמָא חַד סְפַר מוֹשִׁט תַּרְגוּמָא מִן גַּו סִיפְרָא. אֲמַר לֵיהּ. "אֲסִיר לָךְ! דְּבָרִים שֶׁנֶּאֶמְרוּ בַפֶּה בַפֶּה וּדְבָרִים שֶׁנֶּאֶמְרוּ בִכִתָב בִּכְתָב."

Rabbi Ḥaggai (also) relates: Rabbi Samuel bar Rav Isaac went to a synagogue. He saw a scribe reciting the translation from a scroll. [Rabbi Samuel] said to him: “This is forbidden! Matters which were said orally, must be delivered orally; matters which were said in writing, must be delivered in writing.”

The passage highlights three “rules” regarding Targum:

- Targum must be delivered standing upright (i.e., with good posture);

- The meturgeman (or person performing the Targum) cannot be the same person that reads from the Hebrew scroll.

- The Targum must be performed on the spot or from memory, not read from a scroll.

The meturgemanim seem to have enjoyed significant freedom in their translations,[14] which may have facilitated the development of a “standard” translation that was, despite Rabbinic regulations, put down into writing. Written targumim were likely in circulation as early as the second/third century C.E., though our earliest extant written manuscripts date to the eighth century. The extant written targums can be broadly divided into two traditions:

Babylonian Targums, specifically Targum Onkelos on the Torah and Targum Jonathan on the Prophets. These Targums are traditionally attributed to Aquilas the proselyte and Jonathan ben Uzziel. Despite being called Babylonian Targums, the Aramaic dialect in which they were written contains many Palestinian elements. This would suggest that their origins lie in Palestine but that their final redaction occurred in Babylonia.[15] These Targums gained authoritative status and were supported by the Babylonian geonim.[16]

Targum Yerushalmi, also known as the Palestinian Targum, with various recensions such as Targum Neofiti and the Fragmentary Targums, as well as pieces of lost Targums found in the repository of the Cairo Genizah. Much less is known about this tradition, though some scholars believe that the extant manuscripts available point to the existence of one single Palestinian Targum from which these recensions developed (i.e., a common Palestinian Targum source).[17] We do not have any extant evidence of this text.

A significant number of Targum manuscripts were produced in medieval Europe, which is surprising given that the general picture of this period does not suggest a high level of literacy in Aramaic among the general Jewish population. These texts underwent constant evolution[18] even in this later period:

Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, likely a medieval European Targum, seems to be a synthesis of Targum Onkelos and the Targum Yerushalmi.[19] It gets its name due to confusion caused by its abbreviation ת’’י (Targum Yerushalmi) which was mistakenly interpreted as Targum Jonathan.

Some Targums to the Writings, such as Targum Chronicles,[20] have been classified as late Targums.

Liturgical Targums, Targum texts transmitted as sections in liturgical manuscripts. In some medieval European Jewish communities, special sections of the Targum were read on specific festival days, the seventh day of Pesach and the first day of Shavuot.[21]

Though we cannot be certain if this tradition is a remnant of the ancient practice of Targum, it is remarkable that the Targum continued to be read in the synagogue, despite the knowledge of Aramaic being scarce among the general Jewish population.[22] (Some Yemenite communities continue this ancient practice today.)

The Liturgical Targum, like the recensions of the Palestinian Targum, is characterized by large insertions within the translation of the Hebrew text. These midrashic expansions—also known as tosefta (pl. toseftot)[23]—that appear in between the verses most often serve to contextualize or expand the verse to which they are attached. In the case of the two lion’s story, however, this is not the case.

The Lions in the Targum

The third verse in the Song of the Sea reads:

שמות טו:ג יְ־הֹוָה אִישׁ מִלְחָמָה יְ־הֹוָה שְׁמוֹ.

Exod 15:3 YHWH the warrior; YHWH is His Name.

A 15th-century Italian mahzor (Parma, Biblioteca Palatina, MS 3003)[24] begins with a straightforward Aramaic translation:

תרגום ליטורי שמות טו:ג ייי[25] גיברא עביד קרבא ייי שמיה.

Liturgical Targum Exod 15:3 The LORD is a warrior, the LORD is his name.

This is followed by a brief expansion adding more examples of God’s greatness, and ending with a blessing:

כשמיה כן גבורתיה כן תוקפיה כן מלכותיה. יהא שמיה רבא מברך לעלם ולעלמי עלמין.

As his name thus is his strength, thus is his might, thus is his kingdom. May his great name be blessed forever and ever.

At this point, the targum adds a tosefta/expansion, dealing with when Moses (without Aaron) first approaches Pharaoh:

והוה כד איתגלי ייי למשה ושיגר יתיה קדם פרעה רשיעא. ואמר ליה זיל קדם פרעה רשיעא ואמור ליה אלהא דעיבראי שיגר יתי קדמך כדי שתשגר ית עמיה ויפלחון קדמוהי במדברא.

It happened when the Lord revealed himself to Moses, that he sent him off before Pharaoh the wicked. He said to him: “Go before Pharaoh the wicked and say to him: ‘The God of the Hebrews sent me before you so that you may send (out) his people, that they may worship before him in the wilderness’.”

At this point, Moses encounters the lions in a similar scene to that of the Chronicles of Moses, with a new detail that the usual way of dealing with the lions is by feeding them meat:

ואזל משה בתרע פלטין והוו בתרע פלטין אריוותא די כל אינש דהוה בעי למיזל קדם פרעה הוה רמי להון בישרא דהוו דחלין מן קדמיהון.

Moses went to the gate of the palace, and at the gate of the palace were lions, so that anyone who wanted to come before Pharaoh would throw meat, because they were afraid of them.

Here too the lions love Moses, though without any description of Moses using his staff as a magical tool to produce this effect:

וכד אתא משה נפקו אריוותא בחדוא סגיא ככלבא מן קדם קיריס דידיה כד אתא מן חקלא.

When Moses came, the lions went out with great joy, like a dog (does) for his master when he returns from the field.

Though shorter than the Chronicles’ version, Moses’ meeting with Pharaoh more or less follows the same contours:

ואתא משה קדם פרעה ואמר ליה אלהא דעיבראי שיגר יתי קדמך די תשגר ית עמיה ויפלחון קדמוהי במדברא. אמר ליה פרעה זיל כען וחזור קדמי בשעתא אוחרן.

Moses came before Pharaoh and said to him: “The God of the Hebrews sent me before you so that you may send out his people, that they may worship before him in the desert.” Pharaoh said to him: “Go now and return to me in an hour.”

Pharaoh then holds a conference with his sorcerer advisors (though Balaam is not mentioned):

מיד שגר פרעה לקביל חרשיא ואתו כולהון קדם פרעה אמר להון פרעה אתא גבי חד יהודאי ואמר לי אלהא דעיבראי שיגר יתי קדמך די תשגר ית עמיה ויפלחון קדמוהי במדברא.

Immediately, Pharaoh sent for the sorcerers and all of them came before Pharaoh. Pharaoh said to them: “One of the Jews[26] came to me and said to me: ‘The God of the Hebrews sent me before you so that you may send out his people, that they may worship before him in the desert’.”

ענו חרשיא ואמרין ליה היך אתא קדמך מן קדם אריוותא דבתרעך אמר להון פרעה אילין אריוותא איתעבידו קדמוהי כתעלייא.

The sorcerers answered and said to him: “How did he come before you, despite the lions that are at your gate?” Pharaoh said to them: “These lions were made (to act) like foxes before him.”

Instead of responding that they acted joyously, like frolicking dogs (as narrated above), Pharaoh responds that they acted “like foxes.” This may be a reference to the sly, nervous nature of foxes, but this contrasts oddly with how they went out happily to greet Moses. Alternatively, the root תעל has been attested in Syriac to mean “to wag the tail.”[27] Though grammatically the form would not make sense in this case, there may be a link between this verbal root and the behavior of the foxes.

Then the advisors make the familiar claim that Moses is simply another sorcerer:

ענו חרשייא ואמרין ליה אילין סימנייא דאתאמר חרש הוא כוותנא.

The sorcerers answered and said to him: ‘These are spells that he has cast [lit. omens that he has spoken]; he is a sorcerer, like us.”

What is this midrash doing as part of the targum of the Song of the Sea?

The Tosefta’s Placement

Though we do not know how widespread the tradition of reading the Liturgical Targum in the European synagogue was, as time went on, this practice became less and less common. Most likely, this was due to a diminishing knowledge of Aramaic among medieval European Jews, and consequently a reduced liturgical prominence for Targum,[28] though it might also be because a full Targum reading in addition to the mandatory Hebrew reading resulted in ceremonies that lasted too long.

And yet, even for Pesach and Shavuot, the Targum reading is only partially preserved in the medieval manuscripts available to us; in many of them only the Targum for the Song of the Sea (Exod 14:30–15:18) was copied and expanded upon. This may simply be a case of the Targum reading being shortened to only the most interesting parts.

Cutting out most of the targum in liturgical readings left scribes and copyists with a dilemma, since it meant leaving out extensive midrashic expansions that were especially interesting or popular. As a result, scribes moved preexisting expansions to verses that were still being read, so they could preserve the cultural heritage,[29] adapting it into the new setting.

Who Is Adonai?

The next part of this tosefta from the Liturgical Targum in the Mahzor (Parma, Biblioteca Palatina, MS 3003) strengthens this supposition, as it expands upon the next scene from Exodus 5:

מיד שיגר פרעה לוות משה ואתא משה קדם פרעה אמר ליה פרעה מאי אמרת לי אמר ליה משה אלהא דיעבראי שיגר יתי קדמך כדי תשגר ית עמיה ויפלחון קדמוהי במדברא

Immediately, Pharaoh sent for Moses and Moses came before Pharaoh. Pharaoh said to him: “What did you say to me?” Moses said to him: “The God of the Hebrews sent me before you so that you may release his people, that they may worship before him in the desert.”

The midrash continues with Moses telling Pharaoh God’s name, connecting the current placement of the midrash to the Song of the Sea:

אמר ליה פרעה מה שמיה אמר ליה משה ייי שמיה כשמיה כן גבורתיה.

Pharaoh said to him: “What is his name?” Moses said to him (Exod 15:3): “Adonai (=the LORD) is his name, like his name, so is his strength.”

Next the midrash expands on Pharaoh’s denial of knowing the Israelite God, by asking Moses questions about this deity, giving Moses (and the midrash) the opportunity to expand on God’s greatness:

אמר ליה פרעה מאי עיבידתיה אמר ליה משה יצר ית ינוקא בכריסא דאימהון והוא ברא יתך בכריסא דאימך.

Pharaoh said to him: “What are his deeds?” Moses said to him: “He formed the suckling child in his mother’s womb, and he created you in your mother’s womb.”

אמר ליה פרעה כמה אוכלוסין אית לאלהך אמר ליה משה אלף אלפין ישמשוניה וריבוא ריבבן קדמוהי יקומון.

Pharaoh said to him: “How many troops does your God have?” Moses said to him (cf. Dan 7:10): “Thousands of thousands will serve him; great multitudes will stand before him.”

This offends Pharaoh’s honor, and he denies the existence of such a deity:

אמר ליה פרעה לית כדבא בעלמא כוותך דאנא בראתי יתי וית נהרא הדין ייי לית אנא ידע וישראל לית אנא משגר:

Pharaoh said to him (cf. Ezek 29:3): “There has never been a lie such as yours. For I have created myself and this river. Adonai, I do not know, and Israel, I will not let go.”

The ending here echoes the very next biblical verse:

שמות ה:ב וַיֹּאמֶר פַּרְעֹה מִי יְ־הֹוָה אֲשֶׁר אֶשְׁמַע בְּקֹלוֹ לְשַׁלַּח אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל לֹא יָדַעְתִּי אֶת יְ־הֹוָה וְגַם אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל לֹא אֲשַׁלֵּחַ.

Exod 5:2 But Pharaoh said, “Who is YHWH that I should heed him and let Israel go? I do not know YHWH, nor will I let Israel go.”

The artificiality of this expansion’s placement is clear from how the next line simply returns to translating the Hebrew text of the Song:

שמות טו:ד מַרְכְּבֹת פַּרְעֹה וְחֵילוֹ יָרָה בַיָּם וּמִבְחַר שָׁלִשָׁיו טֻבְּעוּ בְיַם סוּף.

Exod 15:4 Pharaoh’s chariots and his army He has cast into the sea; and the pick of his officers are drowned in the Sea of Reeds.

The Targum here hews pretty closely to the original:

תרגום ליטורגי טו:ד ארתיכוהי דפרעה וחיליהון כסון עליהון מוי דימא שפר עולימי גיברוי רמא וטבע יתהון בימא דסוף.

Liturgical Targum, Exod 15:4 Pharaoh’s chariots and his army, the waters of the sea covered them. The best of his young warriors, he cast them down and drowned them in the Sea of Reeds.

The manuscript authors, forced to shrink the targum section to small bits, made an effort to grab other pieces of targum that seemed to them especially significant, and place them inside what was left.[30] On one hand, this illustrates the enormous flexibility that the genre of Targum granted its authors, who felt free to amend and adapt its contents to secure the preservation of their cultural heritage. On the other hand, it paints an intriguingly complicated picture of the Targum’s place in medieval Jewish liturgy.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

January 26, 2026

|

Last Updated

February 10, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Jeroen Verrijssen is a postdoctoral fellow at Ghent University, investigating the reception of biblical genealogies in Jewish and Christian sources. He holds a Ph.D. in Religious Studies from KU Leuven, and is the author of The Liturgical Targum (Brill 2026), which examines Aramaic biblical translation in medieval European Jewish liturgy.

Essays on Related Topics: