Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Purimfest 1946: The Nuremberg Trials and the Ten Sons of Haman

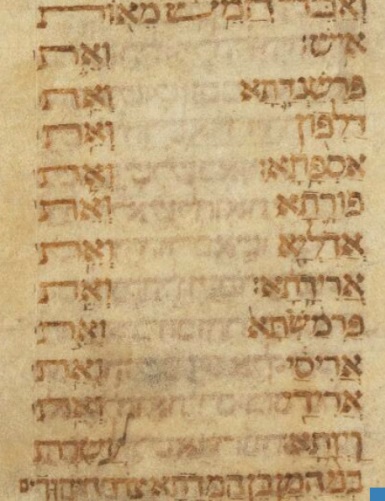

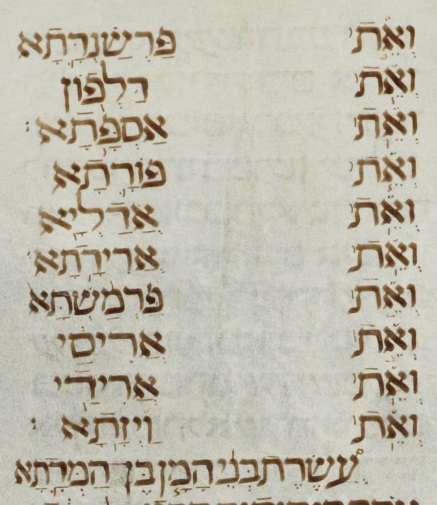

The three small letters and the large vav in the ten sons of Haman, with the Nuremberg trial in the background.

Streicher and the Nuremberg “Purimfest”

Twenty-four defendants were tried at the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals (Nov 20, 1945–Oct 1, 1946). Two were acquitted, eight were given prison sentences, and twelve were condemned to death. Of these twelve, Martin Bormann was tried in absentia,[1] and Herman Goering committed suicide before he could be executed. Given their military status, the ten men asked for the firing squad, but to underscore that their crimes went beyond mere military offenses, the court decided on the more common death by hanging.[2]

Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Kingsbury Smith[3] of the International News Service was chosen by lot to represent the American press at the executions.[4] He reported Streicher’s final moments and last words as follows:

As the guards stopped him at the bottom of the steps for identification formality he uttered his piercing scream: “Heil Hitler!”[5] The shriek sent a shiver down my back… As he reached the platform, Streicher cried out, “Now it goes to God.” He was pushed the last two steps to the mortal spot beneath the hangman’s rope. The rope was being held back against a wooden rail by the hangman. Streicher was swung suddenly to face the witnesses and glared at them. Suddenly he screamed, “Purim Fest 1946.”…

The American officer standing at the scaffold said, “Ask the man if he has any last words.” When the interpreter had translated, Streicher shouted, “The Bolsheviks will hang you one day.” When the black hood was raised over his head, Streicher’s muffled voice could be heard to say, “Adele, my dear wife.” At that instant the trap opened with a loud bang. He went down kicking.”[6]

Apparently, Streicher could not help but notice the parallels of the hanging of ten Nazis and the hanging of Haman’s ten sons.

The Nazi’s Preoccupation with Purim

As historian Martin Gilbert notes, the Nazis were well aware of the Jewish holidays and used “Jewish festivals for particular savagery; these days had become known to the Jews as the ‘Goebbels calendar,’”[7] and many atrocities were committed specifically on Purim.[8]

In Zdunska-Wola, for example, on Purim 1942, ten Jews were hung by Nazis “in revenge for Haman.”[9] On Purim of 1943, the Nazis fooled the Jews of the Piotrkow ghetto—a demonic version of a Purim prank—by asking for ten Jewish volunteers as part of an alleged exchange program for Germans living in Palestine, and then shot them all.[10]

Julius Streicher himself, founder and editor-in-chief of the weekly German newspaper Der Stürmer (“The Stormer”), featured a lengthy report on March 1934 (Der Stürmer 11): “The Night of the Murder: The Secret of the Jewish Holiday of Purim is Unveiled.”[11] On the day after Kristallnacht (November 10, 1938), Streicher gave a speech to more than 100,000 people in Nuremberg in which he justified the violence against the Jews with the claim that the Jews had murdered 75,000 Persians in one night,[12] and that the Germans would have the same fate if the Jews had been able to accomplish their plan to institute a new murderous “Purim” in Germany.[13]

In 1940, the best-known Nazi anti-Jewish propaganda film, Der Ewige Jude (“The Eternal Jew”), took up the same theme.[14] Hitler even identified himself with the villains of the Esther story in a radio broadcast speech on January 30, 1944, where he stated that if the Nazis were defeated, the Jews “could celebrate the destruction of Europe in a second triumphant Purim festival.”[15]

Jews and Nazi-Purim Parallels

The Jews at the time also saw parallels between Purim and the events in Nazi Germany. Already in the 1930s, European Jews connected Haman and Hitler, taking particular joy in the Megillah reading, especially at the hanging of Haman’s sons, interpreting it as the eventual downfall of the Nazis.[16]

Hitler as a modern version of Haman appears in Purim plays going back at least to 1934,[17] and this image figures prominently in the first Purim celebrations held by Holocaust survivors.[18] Rabbinic letters at the time refer to him as the “known Haman” of the time.[19] Photographs of the Purim celebration at the Lansberg DP camp show multiple versions of Hitler hanging in effigy in the fashion of Haman.[20]

Unsurprisingly, therefore, an editorial on the Nuremberg trial in the Tel Aviv daily newspaper HaBoker (Oct 16, 1946, p. 2) as well as a front-page article in this paper discussing the Nuremberg trials (Oct 18, 1946) refer to the Nazis as “sons of Haman.”

The Nuremberg Trials Coded in the Megillah

In a letter to the newspaper Shearim, April 12, 1967,[21] Aharon Goldberger noted that the list of Haman’s ten sons (Esth 9:7–9) contain three letters that according to tradition are written in smaller script: tav, shin, zayin, whose numeric value in gematria is 707 (400+300+7). This, he argued, is a hidden reference to the Jewish year (5)707, during which the execution of the ten Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg took place.

Goldberger writes that “unfortunately I do not remember who pointed this out to me.” While some attribute the teaching to R. Mordechai Schwab,[22] others to R. Aharon Rokeach[23] or R. Michael Ber Weissmandl,[24] the teaching is generally brought without any attribution.[25] The teaching gained prominence in the 1980s, with the publication of Nosson Munk’s article in the March 1986 issue of the American Orthodox magazine Jewish Observer as well as in two articles in the Israeli Charedi newspaper Yated Neʾeman (“The Faithful Peg”).[26]

At the same time, this teaching was popularized through its use in outreach work— as part of Aish HaTorah Discovery Seminars and similar programs—in the context of demonstrating the divine origin of the Torah.[27] From there, books, articles, and lectures[28] propagate the idea that the letters are a prophetic prediction of the Nuremberg trial.[29] The Esther code has even inspired a best-selling French book, presented as investigative journalism,[30] and an American thriller in which an FBI agent deciphers Queen Esther’s prophecy with the help of a rabbi and finally arrests a serial murderer.[31]

Creative Additions to the “Code”

Depending on the publication, the core teaching (ten sons=ten Nazis, small letters=Hebrew date) is often supported with further ostensible points of contact between the Purim story and the Nuremberg executions:

The large vav—The name Vayzata is written with a large vav, which is understood as a marker of the sixth millennium, thus filling out the year 5707.

Haman’s Daughter—The suicide of Hermann Goering is said to correspond to the death of Haman’s daughter before the war, as recorded in the Talmudic legend (b. Megillah 16a):

כי הוה נקיט ואזיל בשבילא דבי המן חזיתיה ברתיה דקיימא אאיגרא סברה האי דרכיב אבוה והאי דמסגי קמיה מרדכי שקלה עציצא דבית הכסא ושדיתיה ארישא דאבוה דלי עיניה וחזת דאבוה הוא נפלה מאיגרא לארעא ומתה והיינו דכתיב ...והמן נדחף אל ביתו אבל וחפוי ראש אבל על בתו וחפוי ראש על שאירע לו

When he (Haman) was going along the read by Haman’s house (leading Mordechai on the king’s horse), his daughter who was standing on the roof saw him. She thought that the person riding was her father and the one going before him was Mordechai. She took a chamber pot and threw it on her father’s head. She dropped her eyes and saw that it was her father, and she fell from the roof to the ground and died. And this is what it means when it says (Esth 6:12): “…and Haman returned to his home in mourning and with his head covered.” He was mourning for his daughter and his head was covered with the contents of the chamber pot.[32]

Hoshana Rabbah—This is an especially fitting day for the execution of Nazis as according to Midrash Tehillim (17:5), this is the day that the angels announce that the Jews are victorious,[33] and it is the day according to the Zohar (Tzav 31b) that judgment of the world is completed.

ואת—That each son’s name is preceded by the accusative marker ואת (veʾet) teaches us, based on the homiletical principle of finding meaning in this particle (b. Ketubot 103a), that something more will occur, namely, the execution of the next set of ten enemies of the Jews.[34]

The Hanging—The hanging of the Nazi criminals as opposed to death by firing squad was part of the divine plan to highlight the connection to the Purim story. Indeed, why else would Esther have insisted on the already deceased sons of Haman being hanged?

Tomorrow—Esther asks for the sons of Haman to be hanged מָחָר “tomorrow” (Esth 9:13), a veiled reference to the much later hanging of the ten Nazis.

All of these connections are creative embellishments of the core “code” of the three small letters; tav, shin, zayin in the names of Haman sons. But what do we know about the history of these small letters?

Haman’s Ten Sons: The Uniqueness of the List

The list of Haman’s sons is treated as an unusual biblical text in several ways. A well-known custom, going back to Talmudic times (j. Megillah 3:7), is the requirement to read the list of Haman’s sons in one breath.

ר' חייה בריה דר' אדא דייפוי ר' ירמיה בשם ר' זעירא: צריך לאמרן בנפיחה אחת ועשרת בני המן עמהן

R. Hiyya the son of R. Ada of Jaffa, R. Jeremiah in the name of R. Zeira: “They (=the list of Haman’s ten sons) must be recited in one breath, and [the words] ‘the ten sons of Haman’ with them.”[35]

After noting this rule,[36] the Babylonian Talmud explains (b. Megillah 16b):

מאי טעמא כולהו בהדי הדדי נפקו נשמתייהו.

Why? Because their souls all departed together.

This passage is also written in a special format.

Stacks of Words

The Jerusalem Talmud states that the sons of Haman should be written as stacks of words (j. Megillah 3:7):

ר' זעירה ר' ירמיה בשם רב שירת הים ושירת דבורה נכתבין אריח ע"ג לבינה ולבינה ע"ג אריח עשרת בני המן ומלכי כנען נכתבין אריח ע"ג אריח ולבינה ע"ג לבינה דכל בינין דכן לא קאים...

R. Zeira, R. Jeremiah in the name of Rav: “The Song of the Sea (Exod 15) and the Song of Deborah (Judg 5) should be written space atop brick and brick atop space. The ten sons of Haman and the kings of Canaan (Josh 12) should be written space atop space and brick atop brick, because such a building cannot remain standing….”[37]

After noting this rule,[38] the Babylonian Talmud offers a slightly different explanation (b. Megillah 16b):

מאי טעמא? [אמר רבי אבהו:][39] שלא תהא תקומה למפלתן

Why? [Rabbi Abahu said:] “So that there will be no rising from their fall.”

The Jerusalem Talmud expands on how the columns should be formatted:

א"ר יוסי בי רבי בון צריך שיהא איש בראש דפא ואת בסופה שכן הוא סליק[40] ונחית כהדין קינטרא.

R. Yossi son of Rabbi Bun says: “[The word] ʾish (“man”) must be at the top-(right) of the column and [the word] veʾet on the left, so that it rises [or “is tight”] and drops like an iron-tipped staff.”[41]

In other words, the left column should consist only of the word ואת, making it a perfectly straight line.

Vayzata with a Large Vav

A third unique feature, recorded in b. Megillah 16b, is:

אמ' ר' יונה אמ' ר' זירא האי וו דויזתא צריך למיזקפיה ולמימתחיה.[42]

Rabbi Yonah said that R. Zeira said: The vav of [the name] Vayzata must be straightened on top and extended downwards.”[43]

As it did for the other two rules, the Bavli includes a reason:

מאי טע[מא]? כולהו בחדא זקיפא איזדקפו.

Why? Because they were all impaled on one pole.[44]

Medieval interpreters debated the meaning of this injunction. Some argued that it refers to how the letter is read, the speaker must elongate the sound,[45] others that the requirement is to write the letter without the horizontal line on top (i.e., like a pole),[46] while the majority assume the letter should be large, extending farther down than most vavs. Perhaps both a flap top and an extended bottom are both implied, thus giving it the form of a long stick upon which a body is impaled.

Do the MSS Follow the Rules?

Two manuscripts, a 13th/14th century Sephardic megillah (Parma 2836), and a Bible completed in 1494 (Paris, hebr. 29 [folio 386r]) follow all the Talmudic prescriptions about how to write this section of the Megillah. (Notably, Parma 2836 also has a small shin in Parmashta, but no other small letters.)

|

|

| Parma 2836 | Bible 1494 (Paris, hebr. 29) |

Other medieval biblical manuscripts don’t follow these rules consistently. For example, the Leningrad Codex (1008 C.E.) does not have a unique looking vav in Vayzata.[47] While it does have the sons of Haman in two columns, the right column doesn’t begin with איש but with מאות איש, two words instead of one.[48] A Sephardic codex dated to the 14th/15th century (Cambridge Add. Ms 652 [folio 302r]) has the elongated vav but the column begins with ואת, not איש, and ends with ויזתא instead of עשרת. Most significantly, it has the ואת column on the right side instead of the left.

|

|

| Leningrad Codex | Cambridge Add. Ms 652 |

The Small Letters of the Megillah

The use of small letters, unmentioned in the Talmud, begins to appear in medieval times. The earliest text we have for this is a late 1st millennium pseudonymous composition listing all the small letters in alphabetical order, known as מדרש עקיבה בן יוסף על אותיות קטנות וטעמיהן “Midrash of Rabbi Akiva ben Yosef on Small Letters and their Reasons.”[49] It is part of a corpus of such works attributed to Rabbi Akiva since he is famous for offering homiletical interpretations of such small nuances (b. Menachot 29b). Here is the list of the small letters of the Megillah:

זיי"ן, ויזתא ז' קטנה, לפי שהמן הלשין בשבעה דברים.

The zayin of the name Vayzata is written small, because Haman slandered seven times the Jewish people.

רי"ש של פרשנדתא קטנה, שנתמעט ונתלה.

The resh of the name Parshandata is written small, because he was lowered and hung.

שי"ן תי"ו של (פרשנדתא) [ס"א פרמשתא] קטנות.[50]

The shin and the tav of (Parshandata) [or: Parmashta] are written small.

In this case, the gematria would be 907; the resh adds another 200. Notably, the text lists four small letters, and they all appear in the ten sons of Haman, specifically in the names of Vayzata, Parshandata, and Parmashta. (They are always limited to these three names.)

A related text, מדרש עקיבה בן יוסף על אותיות גדולות וטעמיהן “Midrash of Rabbi Akiva ben Yosef on Large Letters and their Reasons,” mentions the vav of Vayzata, familiar from the Talmud, and two further examples from other parts of the Megillah: the chet of חור (Esth 1:6) and the first tav of ותכתוב (Esth 9:29).[51]

Medieval Germany

The earliest halakhic work that codifies any small letters in the Megillah is that of the German sage[52] R. Eliezer ben Joel haLevi (Raʾaviah ca. 1140–1225) in his compendium on the Talmud (Megillah, §548):

אל"ף שבפרשנדתא קטנה, דפרמשתא גדולה, ויש אומר היפך.

The aleph in Parshandata should be small, in Parmashta, it should be big. Some say the opposite.[53]

Raʾaviah’s tradition is unrelated to the Rabbi Akiva list, but his contemporary, R Elazar of Worms (ca. 1160–1238), records the practice in the list, minus the small resh of Parshandata,[54] and gives a different explanation for them (Rokeach §235):

תסיר ח' של חור שהיא גדולה שלבש ח' בגדי כהונה שאין חיור כמותן אבל ממעשה דמרדכי ואילך ה' אותיות משונות שתזו"ת בגי[מטריה] כתב זאת זכרון לכך משונין בגודלן ובקרוין.

Put aside the chet of chur (“white,” Esth 1:6), which is big to teach us that he (Ahasuerus) wore the eight layers of the priestly garb, which are unequaled by anything in whiteness. But from the appearance of Mordechai and on there are five strange letters, shin, tav, zayin, vav, tav. In gematria[55] this equals “Write this as a remembrance” (Exod 17:14). This is why they are unusual in their size and how they are read.

All three small letters, together with the large vav and the large tav—the latter of which is not part of the ten sons of Haman text—has a combined numerical value of 1113, the same value as the first three words God commands Moses about Amalek, כתב זאת זכרון “write this as a remembrance,”[56] highlighting the connection between the Megillah and the Amalek story already implicit in the Megillah itself.[57]

France and Provence

In France, the earliest evidence we have for small letters appears in the late 12th century expanded version of the Machzor Vitry,[58] which includes all three large letters, plus the small zayin of Vayzata.[59] Around the same time, R. Avraham ben Natan of Lunel has small letters in all three names and plus a large yod in Vayzata, not found in earlier sources (Sefer HaManhig, “Laws of Megillah” 1.250):

תי"ו זעירא פרשנדתא... שי"ן זעירא פרמשתא... וי"ו ויו"ד רבתי וז' זעירא ויזתא...

Parshandata has a small tav… Parmashta has a small shin… Vayzata has a large vav and yod and a small zayin…[60]

The first halakhic source to record the small and large letters as we have them today was R. Aaron ben Jacob HaKohen of Lunel (early 14th cent.) in his Orchot Chayim (Laws of Megillah and Purim, §17):

ואלו האותיות הגדולות והקטנות שבה ח' של חור כרפס גדולה ו' דויזתא גדולה ת' ראשונה של ותכתוב גדולה ז' של ויזתא קטנה ת' דפרשנדתא קטנה ש' דפרמשתא קטנה.

These are the large and small letters in [the Megillah]: Chet of “white [chur] and green” is big; vav of Vayzata is big, the first tav of “and she wrote [vatikhtov]” is big; the zayin of Vayzata is small; the tav of Parshandata is small; the shin of Parmashta is small.[61]

The practice of writing small letters in the sons of Haman ossified not long after this, thanks to Johannes Guttenberg’s introduction of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century.

The Mikraot Gedolot

In Venice, Daniel Bomberg’s press printed the first edition of Mikraot Gedolot (the Rabbinic Bible) in 1516–1517. His second edition (1524–1526) became the basis for the widely diffused printed biblical text. In preparation for this printing, the publisher, Jacob ben Ḥayim ibn Adonijah (1470–1538), devoted immense efforts to clarify the biblical text, based on the manuscripts in his possession.

When deciding on the correct layout for the Megillah, Jacob ben used the version of the tradition which appears in the Orchot Chayim as his source, and thus the small tav of Parshandata, the small shin of Parmashta, and the small zayin of Vayzata, together with the Talmud’s large vav in that same name, became the accepted standard.

For a while afterwards, halakhic works, including the Shulchan Arukh (Orakh Chayim 691), made no mention of these small letters,[62] nevertheless, as time went on, this tradition was taken for granted and other traditions that had been common for centuries were soon relegated to the unknown world of manuscripts and obscure halakhic texts.[63]

New Explanations for the Small Letters

In addition to the explanations for these unusual letters in the medieval sources, some later rabbis offered new suggestions.[64] For example, Rabbi Mordechai Zvi Adler of Uglya (late 19th/early 20th cent.) in his Ir Mivtzar, explains that the small letters in the first two sons indicate what each specifically did to oppress the Jews.[65]

...כתיב כאן בשם פרשנדתא אות ת' זעירא לרמז כי מאתו יצאה הגזרה אשר גזר המן אביו לבטל את בנ[י] י[שראל] מת[למוד] ת[ורה] אשר החיוב עלינו ללמד דבר אחד ת' פעמים...

The name Parshandata here is written with a small tav to hint that he was responsible for the decree Haman his father made against the Jews learning Torah, regarding which we are obligated to learn one matter 400 (tav) times…

... ע[ל] כ[ן] כתיב בשם פרמשתא אות ש' זעירא רומז כי ע[ל] י[די] עצתו גזר המן אביו לבטל מבנ[י] י[שראל] תפילין אשר מצוה להניחם ש' ימים בשנה...

…This is why the name Parmashta is written with a small shin, to hint that it was based on his advice that his father Haman forced the Jews to stop wearing tefillin, which we are commanded to wear 300 (shin) days a year.

For Vayzata, Adler offers a mystical explanation: Vayzata tried to gain astrological power by “having sex six (vav) days a week” (היה פתו"ח בתשמיש בכל ו' ימי החול), except for Shabbat (the 7th day, zayin), during which he would refrain.[66]

R. Joseph Messas of Fez (1892–1974) in his responsa Mayim Chayim 1 (Orakh Chayim 294), writes that each of these three sons of Haman were known by their birth name as well as a nickname formed by dropping one letter.[67]

The Khmelnitsky Pogrom in 5408

While these explanations look for symbolic, numerological, or even historical significance, in the 18th century, the Dutch-Jewish Historian, Menahem Mann ben Solomon Halevi Amelander (d. 1767) suggested an explanation that had contemporary significance for two of the large letters.

The Khmelnytsky pogroms, a series of pogroms against the Jews in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky as part of the 10-year Cossack-Polish War, began in 1648. Throughout the region, Jewish communities were destroyed, with thousands of people being killed and/or displaced.[68] When discussing these pogroms, Amelander noted in his historical work Sheʾerit Yisrael,[69] that some kabbalists see a hint to these massacres in Megillat Esther:

וחכמי האמת אמרו כי גזירות המן אשר נתבטלה בעת ההיא חלה בשנת ת״ח. וכן אותיות ת״ח נרמזים במגילה באותיות גדולות תי״ו של ותכתוב אסתר המלכה וחי״ת של חור כרפס וה' ינקום נקמת בני ישראל.

Those with mystical knowledge have said that the decrees of Haman, which were cancelled at that time, took place in the year (5)408. And this is hinted at in the letters tav and chet that are written large in the Megillah: the tav of “and Esther wrote (vatikhtov) and the chet of “white (chur) and green.” May God avenge the Jews.

These two large letters have the combined numeric value of 400 (tav) and 8 (chet), the year the pogroms began, (5)408. The Esther code follows in the footsteps of Amelander in finding contemporary meaning by seeing the letters as marking a date.

The Barnum Effect

The attempt to find contemporary significance in these small and large letters relies to some degree on the Barnum effect, i.e., when people see general characterizations as related specifically to them.[70] In reality, none of the details in the Megillah point to a hidden prophecy about the Nuremberg trial.

The small letters do not go back to the Megillah’s origins, but to the late first millennium. The large vav, which goes back to rabbinic times, originates in a playful attempt to make the letter look like a pole for impaling. Moreover, the sixth millennium would have been marked by a heh not a vav.[71] As for Esther’s request to hang/impale the sons of Haman, this was a standard way in ancient times of humiliating one’s enemy by displaying their corpse.[72]

The rest of the supporting arguments, such as Goering’s suicide, the repeated use of the accusative marker ואת, and the executions happening on Hoshana Rabbah, rely on midrashic creativity to make the connections. The same is true regarding the so-called “strange details” of the trial such as why they were hanged as opposed to shot,[73] and the fact that only ten Nazis were executed.[74] So why is this Purim Code so popular?

Proving the Bible

In its first appearances, the main point of the Purimfest teaching that Megillat Esther predicts the Nuremberg trial,[75] was to demonstrate that, as unfathomable as it is, the Holocaust is part of God’s plan.[76] While this is still an important aspect of the teaching, its popularity today, in discovery seminars and other such formats, is due to a paradigm shift.

For centuries, biblical texts have been used to predict events in hindsight. In premodern sources of this type, the truth of the Bible is a given and its passages are used as prooftexts to explain the significance of later events.[77] In the modern age, however, the significance of the Bible itself is what needs to be supported.

Nobody needs a proof that the Holocaust was a significant event, or that the Nuremberg convicts were evil. What people of faith need is proof that despite the secular world in which we live, the Bible is indeed the word of God. The correspondence between the Megillah’s small letters and the Nuremberg trial are meant to prove that God is indeed running the world, and that Esther, the traditional author of the Megillah, spoke prophetically about this horrible future slaughter of her people.[78] This, in turn, supports the truth of the Megillah and, by extension, the Torah and Judaism.

The fact that this teaching became so widespread in the Orthodox Jewish community, despite its ambiguous origin and its reliance on vague connections, indicates that the need it fills is a real one, turning the Holocaust from an event causing one to question the existence of God to an event “encoded” in Megillat Esther, which in turn affirms the divinity of the Bible and God’s plan for history—for those looking for such an affirmation.[79]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 16, 2022

|

Last Updated

February 10, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Emmanuel Bloch holds a Ph.D. in Jewish studies from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His recently completed doctoral thesis, written under the co-supervision of Profs. Suzanne Last Stone and Benjamin Brown, examines how and why the concept of female modesty (tsni’ut), which was always understood as a mimetic way of life, has recently morphed into a legal domain of its own. Previously, Bloch was an attorney-at-law in Europe. His mother tongue is French, and he has published academic articles in three languages. Bloch’s work draws mostly from legal philosophy but is enriched by concepts borrowed from the sociology of law and religion.

Dr. Rabbi Zvi Ron is an educator living in Neve Daniel, Israel. He holds a Ph.D. in Jewish Theology from Spertus University and semikhah (rabbinic ordination) from the Israeli chief rabbinate. He is editor of the Jewish Bible Quarterly and has published over sixty scholarly articles on the Bible, Pseudepigrapha, Midrash, and Jewish customs in Tradition, Hakirah, Zutot, Sinai, ha-Ma'ayan, the Review of Rabbinic Judaism, the Journal of Jewish Music and Liturgy, the Jewish Bible Quarterly and others. He is the author of ספר קטן וגדול about all the big and small letters in the Bible and ספר עיקר חסר about variant spellings of biblical words.

Essays on Related Topics: