Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Scribing the Tabernacle: A Visual Midrash Embedded in the Torah Scroll

Vavei Ha‛ammudim – The Vavim that begin the Columns of a Torah Scroll

Yeri‛ot, ‛Ammudim, and Vavim

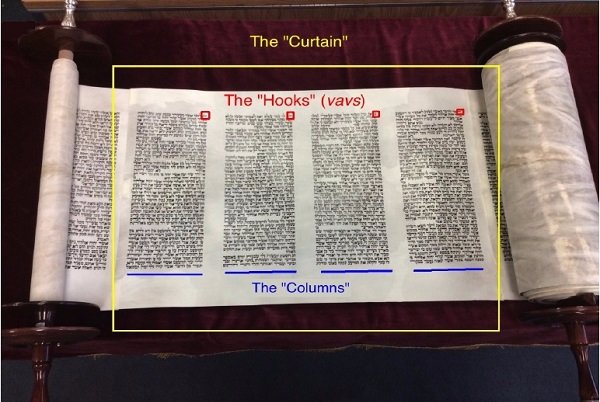

A visual midrash is embedded in plain sight in many of today’s Torah scrolls. If you take a look, you’ll notice that most Ashkenazi and Sephardi Torah scrolls begin each column with the letter vav, a practice referred to as Vavei Ha‛ammudim (ווי העמודים), “the vavs of the columns.” This scribal practice is based on three of the technical terms of the Tabernacle used in this week’s Torah portion (Parashat Terumah), which mirror three of the technical terms of the Torah scroll:

|

Tabernacle |

Torah Scroll |

| יריעות (yeri‛ot) – The “curtains” that cover the Tabernacle (e.g., Exodus 26:32, 37; 27:10). | The pieces of parchment in the Torah scroll are called יריעות (yeri‛ot), the same term as the curtains of the Tabernacle. |

| עמודים (‛ammudim) – The “columns” which hold up the Tabernacle and its accoutrements (e.g., Exodus 26:32, 37; 27:10). | The columns of the Torah scroll are called עמודים (‛ammudim), the same term as the columns of the Tabernacle. |

| ווים (vavim) – The “hooks” attached to the columns that hold up the curtains (e.g., Exodus 26:32, 37; 27:10). | The sixth letter of the Hebrew alphabet is called a וו (vav), the same term as the hooks that were attached to the columns of the Tabernacle. |

The Practice of Vavei Ha‘amudim

These parallel terms inspired 13th century scribes to view the Torah scroll as a representation of the Tabernacle, which led to the practice of the Vavei Ha‛ammudim (ווי העמודים), “the vavs of the columns,” a name based on the same phrase that appears in Exodus 27:10–11 and again in Exodus 38:10–12, 17.

According to this practice, each column (עמוד) of the Torah scroll must begin with the letter vav (וו). Just as the “curtains” of the Tabernacle (יריעות) were held up by the “hooks” (ווים) at the top of the “columns” (עמודים), so too the “curtains” (יריעות) of the Torah scroll should be held up by the “hooks” (ווים) at the top of the “columns” (עמודים).

With the exception of four columns,[2] each and every column in most of today’s Torah scrolls begins with the letter vav. Thus, according to this visual midrash, the Torah scroll is assembled in the same fashion as the tabernacle and is thereby a representation of it.

The Controversy Surrounding the Practice

The scribal practice of the Vavei Ha‛ammudim was not accepted at first.[3] Neither the Talmud nor Maimonides mention the practice and it is not found in the world’s oldest Torah Scroll, ca. 1155-1225. In his glosses on the Mishneh Torah (Hagahot Maimoni, Sefer Torah, 7:9.7), Rabbi Meir ben Yekutiel HaKohen (d. 1298) attacks the practice, calling it forbidden and ignorant. He invokes his famous teacher, Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg (d. 1293), who names the scribe that started the practice:

מה שנהגו סופרים בורים להתחיל כל עמוד בוי”ו וקורין לו וו”י העמודים נראה שאיסור גמור יש בדבר שהרי עושים העמודים יש מהן רחב ויש מהן קצר ופעמים יש אותיות גדולות אשר לא כדת… ופעמים אותיות משונות וארוכות הרבה כדי שיגיע וי”ו לראש כל עמוד…

The current practice of ignorant scribes to begin each column with a vav, and which they call “vavei ha-amudim” appears to be completely prohibited. For those who make these columns, some are wide and some are narrow; sometimes the letters are too big… Sometimes the letters appear strange and too long, in order to allow a vav to appear at the top of each column…

והנה כתבתי דברי אלה למורי רבינו והסכים על ידי וז”ל אשר השיבני וששאלת על ספר תורה בווי העמודים ולא נכון בעיני כמו שכתבת ואינם לא מדברי תורה ולא מדברי סופרים אך סופר אחד היה ר’ ליאונטיין ממילהוז”ן שהראה אומנתו ואילו היה לי לכתוב ספר תורה הייתי נזהר שלא היה שום עמוד מתחיל בוי”ו חוץ מואעידה בם עכ”ל:

I wrote up these thoughts for our Master Rabbi and he agreed with with me answering as follows: “You asked about a Torah scroll with vavei ha-amudim. This practice is inappropriate, just as you wrote. The custom is not found in the Torah or scribal tradition. Instead, there was one scribe named Rabbi Leontin of Mühlhausen, who was showing off his abilities. If I were to write a Torah scroll, I would make sure that no column begins with a vav, except for (Deut 31:28), ‘and I will call witness against them (ואעידה בם).’”

Despite strong initial rejection, as time progressed, the practice of Rabbi Leonitin of Mühlhausen became more and more accepted in both Ashkenazi and Sephardi circles. By the nineteenth century, Rabbi Yechiel Michel Epstein was able to write in the Arukh HaShulḥan (Yoreh Deah 273:24):

וכבר נהגו הסופרים לכתוב אחריו ובוודאי יש נכון וישר לעשות כן ויש בזה ענין גדול.

The scribes already practice this tradition and it is absolutely correct and proper to continue it: this is a very important matter.

In today’s synagogues, it is difficult to find an Ashkenazi or Sephardi Torah scroll that does not follow the practice.[4]

A Textual Connection Between the Tabernacle and the Torah

While the practice of the Vavei Ha‛ammudim expresses the Torah-Tabernacle connection visually, the connection can also be found in Exodus Rabbah 51:7 (likely redacted in the 10th-11th centuries), where the Rabbis wrote:

”משכן העדות“ מה העדות זו תורה שהם יגעים בה.

“The Tabernacle of Testimony” (Exodus 38:21): What is the testimony? This is the Torah in which [Israel] toils.

Finding a Place for the Tabernacle in Modern Times

While the practice of the Vavei Ha‛ammudim may have originally been a playful exercise (“showing off,” as Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg put it), it can also be viewed as innovative, meaningful, and relevant. By drawing a connection between the Torah scroll and the Tabernacle, the practice of the Vavei Ha‛ammudim provides a new venue for the Tabernacle to find a place in contemporary Judaism.

The Torah describes the Tabernacle as a movable dwelling that housed the divine at the center of the Israelite camp. The Torah scroll is itself a type of surrogate for the Tabernacle, having replaced it (and the Temple) as the house of the divine at the center of the synagogue, one of the centers of Jewish life. This idea is expressed visually in each and every Torah scroll by the practice of the Vavei Ha‛ammudim.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 17, 2016

|

Last Updated

February 3, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Rabbi David Z. Moster is the founder and director of the Institute of Biblical Culture and is the lead faculty for the Biblical Hebrew certificate program at the Jewish Theological Seminary. He received his Ph.D. in Biblical Studies from Bar-Ilan University, writing on the biblical tribe of Manasseh. He also holds an M.A. in Ancient Israel and Near Eastern History from New York University and a number of degrees (B.A., M.A., M.S., Semikhah) in Hebrew Bible, Jewish Philosophy, Jewish Education, and Rabbinics from Yeshiva University. His YouTube channel is @BiblicalCulture.

Essays on Related Topics: