Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Bible’s Language: What Is It Called?

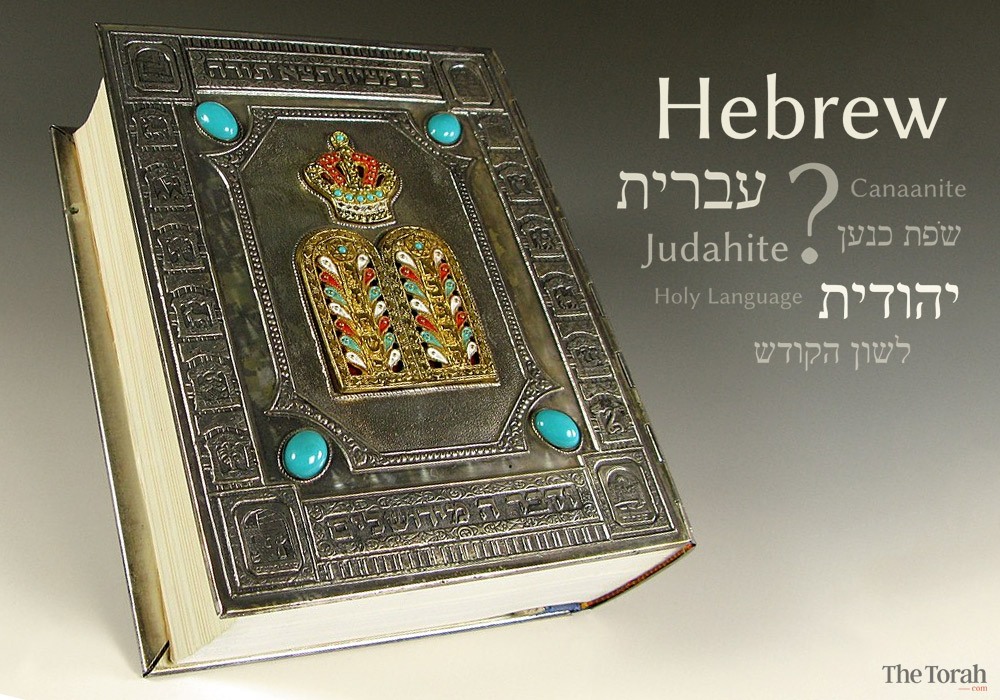

Hebrew Bible given to First Lady Betty Ford by the Jewish National Fund, 1976 (adapted). Wikimedia

When Joseph speaks to Pharaoh, he says that he was kidnapped from אֶרֶץ הָעִבְרִים, “the land of the Hebrews” (Gen 40:15). The daughter of Pharaoh, when she finds Moses, calls him מִיַּלְדֵי הָעִבְרִים, “a child of the Hebrews,” and Moses’s sister seeks מֵינֶקֶת מִן הָעִבְרִיֹּת, “a Hebrew nurse” to care for him (Exod 2:6–7).

The Bible, however, never calls the language in which it is written עברית (ʿIvrit), “Hebrew,” the name used later for the language. Nor are we informed what the inhabitants of the land called their language. Isaiah uses the name שְׂפַת כְּנַעַן (sefat Kenaʿan), although this may be no more than a figure of speech rather than the actual name of the language:[1]

ישׁעיה יט:יח בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא יִהְיוּ חָמֵשׁ עָרִים בְּאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם מְדַבְּרוֹת שְׂפַת כְּנַעַן וְנִשְׁבָּעוֹת לַי־הוָה צְבָאוֹת....

Isa 19:18a In that day, there shall be several towns in the land of Egypt speaking the language of Canaan and swearing loyalty to YHWH of Hosts.[2]

The emissaries of Hezekiah, king of Judah, ask Rabshakeh, the Assyrian general, to refrain from speaking יְהוּדִית (Yehudit), “Judahite,” so that the common people would not understand his demoralizing speech:

מלכים ב יח:כו וַיֹּאמֶר אֶלְיָקִים בֶּן חִלְקִיָּהוּ וְשֶׁבְנָה וְיוֹאָח אֶל רַב שָׁקֵה דַּבֶּר נָא אֶל עֲבָדֶיךָ אֲרָמִית כִּי שֹׁמְעִים אֲנָחְנוּ וְאַל תְּדַבֵּר עִמָּנוּ יְהוּדִית בְּאָזְנֵי הָעָם אֲשֶׁר עַל הַחֹמָה.

2 Kgs 18:26 Eliakim son of Hilkiah, Shebna, and Joah replied to the Rabshakeh, “Please, speak to your servants in Aramaic,[3] for we understand it; do not speak to us in Yehudit in the hearing of the people on the wall.”

Presumably, Yehudit refers to the language of Judah alone, as the people of the northern kingdom of Israel would have had an aversion to such a name for their own language. Nevertheless, the dialects of the two kingdoms were probably similar, as Amos, the Judahite prophet, found no difficulty in making speeches in Samaria, the capital city of Israel (Amos 1:1).[4]

In the post-exilic period, Nehemiah complains about the mixed marriages of many Judahites, and that children of these unions do not know Yehudit:

נחמיה יג:כד וּבְנֵיהֶם חֲצִי מְדַבֵּר אַשְׁדּוֹדִית וְאֵינָם מַכִּירִים לְדַבֵּר יְהוּדִית וְכִלְשׁוֹן עַם וָעָם.

Neh 13:24 A good number of their children spoke the language of Ashdod and the language of those various peoples, and did not know how to speak Yehudit.[5]

Here, Yehudit is the name he uses for the language spoken in the territory under his rule, namely the Persian province of Yehud (Judah). Again, this name would not likely have been by the people in the territory of Samaria at that time (Neh 2:10–19, etc.).

It is only in post-biblical period, i.e., after the events described in the Bible, that the name “Hebrew” is used for the language spoken within the boundaries of the land of Israel. (This does not imply, however, that the name did not exist before this period.)

Hebrew in the Second Century B.C.E.

The first echo of the name “Hebrew” is embedded into the preface of the Greek book of Ben-Sira (2nd cent. B.C.E.), where the author’s grandson, who made the translation, complains about the difficulties in rendering Ebraisti, “Hebrew,” into Greek:[6]

Sir 0:15 You are invited, therefore, 0:16 with goodwill and attention 0:17 to read it 0:18 and to be indulgent 0:19 in cases where we may seem 0:20 to have rendered some phrases imperfectly, despite our diligent labor in translating. 0:22 For it does not have exactly the same effect, 0:22 what was originally said in Hebrew [ἑβραϊστί], when translated into another language.[7]

In addition, the contemporary Letter of Aristeas speaks about the king’s desire to have the Law translated from Hebrew into Greek:

Aristeas § 38 Now since I am anxious to show my gratitude to these men and to the Jews throughout the world and to the generations yet to come, I have determined that your law shall be translated from the Hebrew tongue which is in use amongst you into the Greek language, that these books may be added to the other royal books in my library.[8]

Finally, the book of Jubilees (2nd cent. B.C.E.) reports about God’s speech to Moses, saying that He taught Abraham “the Hebrew language” (12:26–27).[9]

References to the Hebrew language also occur in many somewhat later literary pieces composed in the Roman periods, such as Philo’s (early 1st cent. C.E.) references to the Ebraios glossa, “Hebrew language,” in his De Sobrietate § 45 and De Confusione Linguarum § 68.[10] Josephus’ (1st cent. C.E.) account of Rabshakeh, mentioned above, describes him as speaking in Hebrew, not Yehudit:

Ant. 10:8 As Rapsakēs spoke these words in Hebrew, because he mastered this language, Eliakias was afraid that the people might overhear them and be thrown into consternation, and so asked him to speak in Aramaic.[11]

References to the Hebrew language occur in many other places as well, such as the Gospel according to John:

John 19:13 When Pilate heard these words, he brought Jesus outside and sat on the judge’s bench at a place called The Stone Pavement, or in Hebrew Gabbatha.[12]

Paul addresses a crowd in Jerusalem in the Hebrew language:

Acts 22:2 When they heard him addressing them in the Hebrew language, they became even more quiet.[13]

Hebrew in Rabbinic Texts

The name עברית (ʿIvrit) and its variant עברי (ʿIvri) for Hebrew associated with speech is not widespread in the Tannaitic and Amoraic literature. I found only 41 occurrences in the older rabbinic sources from the beginning of the Common Era to the end of the seventh century, many of which are mere repetitions—passages quoted or re-written from older sources.[14]

ʿIvrit as a language appears mainly in precepts referring to writing of deeds, contracts, and even scrolls. For example, in the Mishnah:

משנה גיטין ט:ח גֵּט שֶׁכְּתָבוֹ עִבְרִית וְעֵדָיו יְוָנִים

m. Gittin 9:8 a writ of divorce written [in] Hebrew with its witnesses [signing in] Greek (quoted in y. Gittin 50c; b. Gittin 19b; 87b).[15]

Likewise in the Tosefta:

תוספתא בבא בתרא יא:ח משנין את השטר מעברית ליוונית.

t. Bava Batra 11:8 A deed may be changed [from] Hebrew to Greek.[16]

The Talmud enumerates Torah writings for which one is permitted to desecrate Shabbat in order to save them from fire:

בבלי שבת קטו. הָיוּ כְּתוּבִין גִּיפְטִית מָדִית עִיבְרִית עֵילָמִית יְוָונִית... מַצִּילִין אוֹתָן מִפְּנֵי הַדְּלֵיקָה.

b. Shabbat 115a If they are written [in] Egyptian, Median, Hebrew, Elamitic, or Greek..., they may be saved from a fire.[17]

Rarely is ʿIvrit used in context of speech. Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael (3rd cent. C.E.) claims that one of the factors that led to the liberation of the Children of Israel from Egypt was the fact that they never abandoned their language and continued to speak Hebrew in the Egyptian environment:

מכילתא דרבי ישמעאל, פסחא, פרשה ה ומנין שלא חלפו לשונם שנ' מי שמך לאיש שר ושפט. מכן שהיו מדברים עברית.

Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Pischa 5 Wherefrom (do we know) that they did not change their language? It is written: “Who made you a ruler and judge over us?” (Ex. 2:14); Therefrom that they were speaking Hebrew.[18]

Sifre Devarim (3rd cent C.E.) says:

ספרי דברים שמג יי מסיני בא זה לשון עברי.

Sifre Devarim §343 The Lord came from Sinai (Deut 33:2)—this is [in the] Hebrew language.[19]

In the Jerusalem Talmud, R. Jonathan of Bet Guvrin, attributing functions to the four important languages of his time, reserves Hebrew for speech:

תלמוד ירושלמי מגילה א:ט, עא: ארבעה לשונות נאים שישתמש בהן העולם ואילו הן לעז לזמר רומי לקרב סורסי לאילייא עברי לדיבור.

y. Megillah 1:9, 71b Four languages are suitable for the world to use them. They are: Laaz (= Greek) for song, Roman for battle, Syriac for elegy, Hebrew for speech.

Notwithstanding its importance in the eyes of the rabbis, the term ʿIvrit remains infrequent in their literature.

The Holy Language in Rabbinic Texts

More frequent is the appellation לשון הקודש (leshon haqqodesh), “holy language,”[20] which occurs around 80 times in the same period (1st – 7th cent. C.E.) in rabbinic literature. It is far more widely used than ʿIvrit, perhaps because of its appreciative connotation. Its origin likely lies in its attribution to the language in which the Bible is transmitted, wherefrom it spread to become the nickname for Hebrew in general.[21]

The oldest Tannaitic document, the Mishnah, specifies that certain formulae are pronounced in leshon haqqodesh. For example, the rite of the חֲלִיצָה, the ritual in which the shoe of the yevam who refuses levirate marriage was removed (Deut 25:7–10), was performed in “the holy language”:

משנה יבמות יב:ו וְהִיא אוֹמֶרֶת: (דברים כה,ז) "מֵאֵן יְבָמִי לְהָקִים לְאָחִיו שֵׁם בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל, לֹא אָבָה יַבְּמִי". וְהוּא אוֹמֵר: (דברים כה,ח) "לֹא חָפַצְתִּי לְקַחְתָּהּ". בִּלְשׁוֹן הַקֹּדֶשׁ.

m. Yevamot 12:6 And she says: “My levir refuses to establish a name in Israel for his brother; he will not perform the duty of levir” (Deut 25:7), and he says: “I do not want to marry her” (25:8). And they say these in the holy tongue.[22]

Leshon haqqodesh is used not only to qualify quotations from the Bible or other formulae, but also to designate spoken Hebrew. For example:

ספרי דברים מו כשהתינוק מתחיל לדבר אביו מדבר עמו בלשון הקודש.

Sifre Devarim §46 When a child begins to speak, his father should speak to him in the holy language.[23]

R. Meir in the same composition says:

ספרי דברים שלג כל הדר בארץ ישראל וקורא קרית שמע שחרית וערבית ומדבר בלשון הקדש האי הוא בן העולם הבא

Sifre Devarim §333 Anyone who lives in the Land of Israel, and recites the creed (שמע ישראל) morning and evening and speaks the holy language, will inherit the world to come.[24]

The Oldest Reference to the Holy Language

The oldest record of the term leshon haqqodesh, and the first known reference in a non-rabbinic source, came to light in a fragment discovered in the fourth cave in Qumran (4Q464).[25] A segment of the document says:

7 [...] עד עולם כיא הואה

8 [...]רא לשון הקודש

9 [...כי אז אהפך] אל עמים שפה ברורה

This last line is a quote from Zephaniah:

צפניה ג:ט כִּי אָז אֶהְפֹּךְ אֶל עַמִּים שָׂפָה בְרוּרָה לִקְרֹא כֻלָּם בְּשֵׁם יְ־הוָה לְעָבְדוֹ שְׁכֶם אֶחָד.

Zeph 3:9 At that time I will change the speech of the peoples to a chosen language, that all of them may call on the name of YHWH and serve him with one accord.”[26]

Esther Eshel and Michael E. Stone thus inferred that the Qumran fragment belongs to the eschatological genre, and that lines 7 and 8 mean that at the “end of the days” people will speak the “holy language.”

Hebrew, the Primeval Language

The belief that Hebrew was the primeval language with which God created the world was quite popular in Jewish circles from time immemorial. The midrash Genesis Rabbah states:

בראשית רבה יח:ד שֶׁנִּתְּנָה תּוֹרָה בְּלָשׁוֹן הַקֹּדֶשׁ כָּךְ נִבְרָא הָעוֹלָם בְּלָשׁוֹן הַקֹּדֶשׁ

Gen. Rab. 18:4 Inasmuch as the Torah was given in the holy language, so the world was created in the holy language.[27]

The medieval Midrash collection Tanhuma maintains that Hebrew was the language that God “confused” at the Tower of Babel (Gen 11) because of human arrogance:

תנחומא (בובר), נח יט שערבב הקב״ה את לשונם... מה היה אותו הלשון שהיו מדברים בו לשון הקודש היה שבו נברא בעולם.

Tanhuma (Buber), Noah 19 That God confused their language and nobody understood his fellow’s language. What was that language that they were speaking? It was the holy language, in which the world was created...

In addition, in the world to come, as prophesied in Zephaniah, Hebrew will regain its status as the universal language:

תנחומא (בובר), נח יט לעולם הבא כולן שוין כתף אחד לעבדו שנאמר כי אז אהפך וגומר.

Tanhuma (Buber), Noah 19 In the world to come all [creatures] will equally worship Him, for it is said: “At that time I will change [the speech of the peoples to a chosen language], etc.” (Zeph 3:9).[28]

Hebrew in Samaritan Texts

Notwithstanding their long-lasting rivalry, Samaritans and Jews have not only common traditions, but some traces of common hopes and even common terminology. For example, a Samaritan poem for the Day of Atonement by the priest אבישע [Abiša] exhibits a remarkably similar eschatology to that of Tanhuma. Going one step further, however, Abiša claims that the Arabic language will be confused and Hebrew will be the language of the Last Days:[29]

וישכן ישראל בטח האמן מן יראתו

Israel will dwell in safety (Deut 38:28), the steadfast in its faith,

ויעבד מועדיו בשלם ויקריב קרבנותו

And he will keep the feasts in peace and make his offerings,

והשמחות תתחדש וכל העמים יכפתו

And joy will be renewed, and all the nations will be subdued,

ויבלל לשן הערבים ויתגלי לשן עבראותו[30]

And the language of the Arabs will be confused and the Hebrew language will be revealed [= reinstated].

The environment in which the Samaritans lived and in which their renaissance took place in the 14th century was Arabic-speaking. The Samaritan community itself spoke and wrote in Arabic as well. Abiša knows that this situation is not going to change in the near future. He expresses his longing for the end of the days, when Hebrew will regain its status of universal language, as it was in the days before the Tower of Babylon, when humanity became multilingual.[31]

The re-birth of Hebrew is for Abiša the hallmark of a global process of the nations’[32] admittance of the true faith:

והגוים והערלים כל מנון יימר לעדתו

And the nations and the uncircumcised, each one of them will say to its community:

כל מה אנן בו שקר וזה הו הקשט דתו

“Everything in which we are is untrue, and this is the true faith.

קומו בנו (!?) נלך אליו ונבוא תחת צל קורתו

Arise, let us go to it and come under the shelter of its roof” (Gen 19:8).

וייתו ויאמנו בו ובמשה ותורתו

And they will come and believe in Moses and his law.

Needless to say, Jews are not going to evade the universal conversion to Samaritanism. They too will acknowledge their error and abandon their law, given to them by Ezra, the father of the Jewish heresy:

היהודהים (!) יימרו זה נבוא בדתו

And the Jews will say: “Let us join this faith;

ארור עזרה ודבריו דכתב בבישאתו

Cursed be Ezra and his words, which he has written in his evilness.”[33]

Holy Language in Samaritan Texts

The Samaritans also employed the phrase לשון הקדש (leshon haqqodesh), often as an introductory formula for a Torah quotation or reference. For example, in a hymn composed by the 10th century poet טביה בן יצחק [Tabya ban Yeʾṣåq] for the first day of the month of Nissan (if it falls on a Sabbath), leshon haqqodesh introduces a quotation from the Song of the Sea:

ואדם בצלם והדמה יאמר בלשן הקדש

And man in the image and likeness says in the holy language:

מי כמוך באלים יהוה מי כמוך נאדרי בקדש

“Who is like You, O Lord, among the gods? Who is like You, majestic in holiness?” (Exod 15:11).[34]

However, the phrase leshon haqqodesh is not reserved exclusively for quotations from the Torah or for eschatological visions. In a poem written by Yusef, the great grandfather of Marḥib,[35] it designates the late medieval Neo-Samaritan Hebrew:

פממי אטהר ולשני אקדש

Let me purify my mouth and purge my tongue,

וארנן ואתפחר בלשן הקדש

And sing and glorify in the holy language,

למן נורו נהיר דלערפלה נגש

The one who his light is kindling, who approached the darkness (Exod 20:21),

דזרח משעיר ודרס לגו אש

Who dawned from Seʿir (Deut 33:2) and trod on the fire (refers to Exod 3:3–6).[36]

Thus, though the names Hebrew language and holy language did not emerge until the post-biblical period, Jews and Samaritans both adopted these terms, adapting them to their traditions and to the needs of their communities.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

October 21, 2025

|

Last Updated

January 28, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Abraham Tal is Professor Emeritus at the Department of Hebrew and Semitic Linguistics of Tel Aviv University, formerly the vice-president of the Academy of Hebrew Language and editor-in-chief of the Historical Dictionary of the Hebrew Language. He holds a PhD from Hebrew University. Among his major publications are A Dictionary of Samaritan Aramaic (Brill, 2000), The Pentateuch – The Samaritan Version (with Moshe Florentin, TAU University Press, 2010), Tibat Marqe – Edition, Translation, Commentary (Studia Samaritana, de Gruyter, 2019), and Samaritan Aramaic (Ugarit Verlag, 2013).

Essays on Related Topics: