Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Burning Bush: Why Must Moses Remove His Shoes?

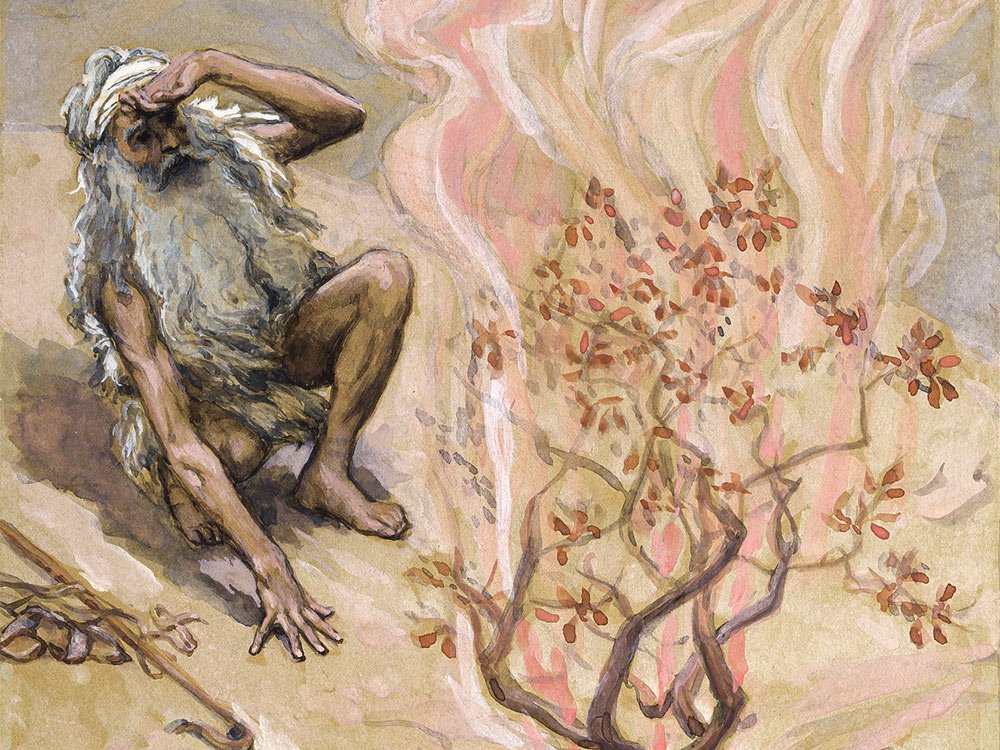

Moses Adores God in the Burning Bush (detail), James Tissot, ca. 1896-1902. Jewish Museum

God first appeared to Moses in Midian while he was shepherding his father-in-law’s sheep:

שמות ג:א וּמֹשֶׁ֗ה הָיָ֥ה רֹעֶ֛ה אֶת צֹ֛אן יִתְר֥וֹ חֹתְנ֖וֹ כֹּהֵ֣ן מִדְיָ֑ן וַיִּנְהַ֤ג אֶת הַצֹּאן֙ אַחַ֣ר הַמִּדְבָּ֔ר וַיָּבֹ֛א אֶל הַ֥ר הָאֱלֹהִ֖ים חֹרֵֽבָה׃

Exod 3:1 Now Moses, tending the flock of his father-in-law Jethro, the priest of Midian, drove the flock into the wilderness, and came to the mountain of God, to Horeb.[1]

Why Is this the Mountain of God?

The text does not tell us why the place is called “the Mountain of God.” One possibility is that it was known to be YHWH’s abode.[2] Alternately, this name could refer to the future revelation that will occur when Moses brings the people there after the exodus from Egypt. As God tells Moses subsequently at the burning bush:

שמות ג:יב ...בְּהוֹצִֽיאֲךָ֤ אֶת הָעָם֙ מִמִּצְרַ֔יִם תַּֽעַבְדוּן֙ אֶת הָ֣אֱלֹהִ֔ים עַ֖ל הָהָ֥ר הַזֶּֽה׃

Exod 3:12 ...And when you have freed the people from Egypt, you shall worship God at this mountain.

This verse refers to the account of the revelation at Horeb—more frequently called Sinai[3]—where the Israelites will receive a set of laws, ratified in a covenant, and then leave on their journey towards the Promised Land. In the words of Sara Japhet, professor emerita of Bible at Hebrew University, “It is the revelation that makes the mountain sacred; hence it is an ad hoc rather than a permanent sanctity.”[4]

To this day, Bible scholars contest its precise geographical location. Is it the site of Jebel Musa, where the Christian monastery stands today in the Sinai Peninsula, or is it closer to Midianite territory in the Gulf of Aqaba, perhaps Jebel al Lawz, where Moses would have pastured his father-in-law’s flocks?[5]

The Burning Bush

The ephemeral nature of Moses’ encounter with God at the site is highlighted by the physical medium of the revelation:

שמות ג:ב וַ֠יֵּרָ֠א מַלְאַ֨ךְ יְ הֹוָ֥ה אֵלָ֛יו בְּלַבַּת אֵ֖שׁ מִתּ֣וֹךְ הַסְּנֶ֑ה וַיַּ֗רְא וְהִנֵּ֤ה הַסְּנֶה֙ בֹּעֵ֣ר בָּאֵ֔שׁ וְהַסְּנֶ֖ה אֵינֶ֥נּוּ אֻכָּֽל׃ ג:ג וַיֹּ֣אמֶר מֹשֶׁ֔ה אָסֻֽרָה נָּ֣א וְאֶרְאֶ֔ה אֶת הַמַּרְאֶ֥ה הַגָּדֹ֖ל הַזֶּ֑ה מַדּ֖וּעַ לֹא יִבְעַ֥ר הַסְּנֶֽה׃

Exod 3:2 An angel of YHWH appeared to him in a blazing fire out of a bush. He gazed, and there was a bush all aflame, yet the bush was not consumed. 3:3 Moses said, “I must turn aside to look at this marvelous sight; why doesn't the bush burn up?”

God’s angel appears in the form of fire in a sneh, commonly translated as a “bush,” likely a blackberry bramble (rubus sanctus).[6] While the scene is miraculous—the bush remains unconsumed by fire—as a plant, the bush itself will eventually wither and die. Unlike stones that might form a monument or an altar and permanently mark a spot, the bush is ephemeral; no man-made trace of this site will remain.[7]

The author may have chosen the unusual term sneh, “bush,” repeated here five times, because it is a homonym for Sinai,[8] connecting this encounter to the future revelation at Mount Sinai.[9] The fire, too, foreshadows the “consuming fire” that will appear on the mountain into which Moses will enter without being consumed:

שמות כד:יז וּמַרְאֵה֙ כְּב֣וֹד יְ הוָ֔ה כְּאֵ֥שׁ אֹכֶ֖לֶת בְּרֹ֣אשׁ הָהָ֑ר לְעֵינֵ֖י בְּנֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃ כד:יח וַיָּבֹ֥א מֹשֶׁ֛ה בְּת֥וֹךְ הֶעָנָ֖ן וַיַּ֣עַל אֶל הָהָ֑ר וַיְהִ֤י מֹשֶׁה֙ בָּהָ֔ר אַרְבָּעִ֣ים י֔וֹם וְאַרְבָּעִ֖ים לָֽיְלָה׃

Exod 24:17 Now the Glory of YHWH appeared in the sight of the Israelites as a consuming fire on the top of the mountain. 24:18 Moses went inside the cloud and ascended the mountain; and Moses remained on the mountain forty days and forty nights.[10]

The Warning

As Moses turns to look at the burning bush, he receives a message:

שמות ג:ד וַיַּ֥רְא יְ הֹוָ֖ה כִּ֣י סָ֣ר לִרְא֑וֹת וַיִּקְרָא֩ אֵלָ֨יו אֱלֹהִ֜ים מִתּ֣וֹךְ הַסְּנֶ֗ה וַיֹּ֛אמֶר מֹשֶׁ֥ה מֹשֶׁ֖ה וַיֹּ֥אמֶר הִנֵּֽנִי׃ ג:ה וַיֹּ֖אמֶר אַל תִּקְרַ֣ב הֲלֹ֑ם...

Exod 3:4 When the YHWH saw that he had turned aside to look, God called to him out of the bush: “Moses! Moses!” He answered, “Here I am.” 3:5 And He said, “Do not come closer...”

The double call, “Moses, Moses” (v. 4), is familiar from earlier revelation accounts, such as God’s call to Abraham at the ‘Aqedah, “the binding of Isaac” (Gen 22:11), or to Jacob before his descent to Egypt (46:2). It is both a summons and a warning, for contact with the deity bodes danger. God also warns against encroaching upon the mountain at Sinai, where the Israelites are restrained from going up lest God break out against them (Exod 19:12–13, 21–24).[11]

Barefoot on Holy Ground

God’s warning is followed by an unusual command:

שמות ג:ה ...שַׁל נְעָלֶ֙יךָ֙ מֵעַ֣ל רַגְלֶ֔יךָ כִּ֣י הַמָּק֗וֹם אֲשֶׁ֤ר אַתָּה֙ עוֹמֵ֣ד עָלָ֔יו אַדְמַת קֹ֖דֶשׁ הֽוּא׃

Exod 3:5 “…Remove your sandals from your feet, for the place on which you stand is holy ground.”

The term qodesh “holy” here connotes that which is set apart, fraught with danger, highly charged, inaccessible.[12] The identification of this place as holy ground—אַדְמַת קֹ֖דֶש—prefigures the limits set against encroaching upon the Holy Mountain of God and the Mishkan (Tabernacle).

Joshua at Jericho: A Parallel Command

The command is repeated (almost verbatim) near Jericho, when an emissary of God, initially mistaken for a mortal man, appears as “captain of the host of YHWH” to Joshua with sword drawn:

יהושע ה:יג וַיְהִ֗י בִּֽהְי֣וֹת יְהוֹשֻׁ֘עַ֮ בִּֽירִיחוֹ֒ וַיִּשָּׂ֤א עֵינָיו֙ וַיַּ֔רְא וְהִנֵּה אִישׁ֙ עֹמֵ֣ד לְנֶגְדּ֔וֹ וְחַרְבּ֥וֹ שְׁלוּפָ֖ה בְּיָד֑וֹ וַיֵּ֨לֶךְ יְהוֹשֻׁ֤עַ אֵלָיו֙ וַיֹּ֣אמֶר ל֔וֹ הֲלָ֥נוּ אַתָּ֖ה אִם לְצָרֵֽינוּ׃ ה:יד וַיֹּ֣אמֶר׀ לֹ֗א כִּ֛י אֲנִ֥י שַׂר צְבָֽא יְ הֹוָ֖ה עַתָּ֣ה בָ֑אתִי וַיִּפֹּל֩ יְהוֹשֻׁ֨עַ אֶל פָּנָ֥יו אַ֙רְצָה֙ וַיִּשְׁתָּ֔חוּ וַיֹּ֣אמֶר ל֔וֹ מָ֥ה אֲדֹנִ֖י מְדַבֵּ֥ר אֶל עַבְדּֽוֹ׃ ה:טו וַיֹּ֩אמֶר֩ שַׂר צְבָ֨א יְ הֹוָ֜ה אֶל יְהוֹשֻׁ֗עַ שַׁל נַֽעַלְךָ֙ מֵעַ֣ל רַגְלֶ֔ךָ כִּ֣י הַמָּק֗וֹם אֲשֶׁ֥ר אַתָּ֛ה עֹמֵ֥ד עָלָ֖יו קֹ֣דֶשׁ ה֑וּא וַיַּ֥עַשׂ יְהוֹשֻׁ֖עַ כֵּֽן׃

Josh 5:13 Once, when Joshua was near Jericho, he looked up and saw a man standing before him, drawn sword in hand. Joshua went up to him and asked him, "Are you one of us or of our enemies?" 5:14 He replied, “No, I am captain of YHWH’s host. Now I have come!” Joshua threw himself face down to the ground and, prostrating himself, said to him, “What does my lord command his servant?” 5:15 The captain of the YHWH’s host answered Joshua, “Remove your sandals from your feet, for the place where you stand is holy.” And Joshua did so.

It is not clear what the purpose of this revelation might be. No future revelation will take place in Jericho, nor does it become a place of worship—the opposite, rather! God destroys the city entirely and then Joshua invokes an oath, presumably of his own initiative, that Jericho may never be rebuilt (Josh 6:27).[13]

Christine Palmer, Professor of Bible at Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary, suggests the two commands have in common Israel’s relinquishing the territories to God:

Jericho is wholly dedicated to God and put under the ban (Josh. 6:17-19). Moses and Joshua remove their sandals in the context of the exercise of a divine claim. In so doing, they acknowledge both YHWH’s dominion and their role as his servants.[14]

But what does this act of stripping off his sandal signify? Why must Moses and Joshua be barefoot?

Unbinding the Shoe and the Halitzah Ritual

The act of removing shoes also appears in the laws of levirate marriage, according to which a man must marry the childless widow of his brother to produce a posthumous heir. If the man refuses to do so, the widow performs the ḥalitzah ritual, the “unbinding of the shoe”:

דברים כה:ט וְנִגְּשָׁ֙ה יְבִמְתּ֣וֹ אֵלָיו֘ לְעֵינֵ֣י הַזְּקֵנִים֒ וְחָלְצָ֤ה נַעֲלוֹ֙ מֵעַ֣ל רַגְל֔וֹ וְיָרְקָ֖ה בְּפָנָ֑יו וְעָֽנְתָה֙ וְאָ֣מְרָ֔ה כָּ֚כָה יֵעָשֶׂ֣ה לָאִ֔ישׁ אֲשֶׁ֥ר לֹא יִבְנֶ֖ה אֶת בֵּ֥ית אָחִֽיו׃ כה:י וְנִקְרָ֥א שְׁמ֖וֹ בְּיִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל בֵּ֖ית חֲל֥וּץ הַנָּֽעַל׃

Deut 25:9 His brother’s widow shall go up to him in the presence of the elders, pull the sandal off his foot, spit in his face, and make this declaration: Thus shall be done to the man who will not build up his brother's house! 25:10 And he shall go in Israel by the name of “the family of the unsandaled one.”

In the book of Ruth, this law undergirds the ceremony that Mr. So-and-So (Peloni Almoni) must undergo in dissociating himself from redeeming Naomi’s land at his own request, lest he “corrupt” his estate by marrying the Moabite woman (Ruth 4:6–9).

רות ד:ט וְזֹאת֩ לְפָנִ֙ים בְּיִשְׂרָאֵ֜ל עַל הַגְּאוּלָּ֤ה וְעַל הַתְּמוּרָה֙ לְקַיֵּ֣ם כָּל דָּבָ֔ר שָׁלַ֥ף אִ֛ישׁ נַעֲל֖וֹ וְנָתַ֣ן לְרֵעֵ֑הוּ וְזֹ֥את הַתְּעוּדָ֖ה בְּיִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃

Ruth 4:9 Now this was formerly done in Israel in cases of redemption or exchange: to validate any transaction, one man would take off his sandal and hand it to the other. Such was the practice in Israel.

This verse suggests that the loosening/removal of the shoe entails release from any claim to inherit or redeem the land of the brother or next of kin.[15]

Hittite legal documents (from Nuzi, a Hurrian city of the 2nd millennium) corroborate that claiming (and therefore dis-claiming) ownership of land was associated with a foot action. In a land sale, the transfer of deed was confirmed by lifting up or placing one’s foot on the territory. The prior owner would lift his foot off the land, and the new owner or heir would lay claim to it by stamping his foot down, asserting his right to the fields and/or house(s) (SMN 2390, 2338). As Christine Palmer notes, “Lifting the foot off the property is a symbolic act of relinquishment.”[16]

The Hittite lifting of the foot and the Israelite stripping off the sandal symbolize the same thing: release of any a claim to the land.[17] By having Moses remove his shoes, God forces him to acknowledge this as holy ground and effectively declare: “No man may lay claim to this place (Sinai).”

Moriah and Bethel

While the revelation to Moses at the burning bush foreshadows YHWH’s revelation to all of Israel upon the mountain, it does not pave the way for the establishment of a cult site in the area. This makes the burning bush story quite different from other stories about holy sites encountered by patriarchs.

Moriah—God tells Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac, and sends Abraham to one of the hills in the land of Moriah. After an angel of YHWH stays Abraham’s hand, Abraham sacrifices a ram in his son’s stead, after which:

בראשית כב:יד וַיִּקְרָ֧א אַבְרָהָ֛ם שֵֽׁם הַמָּק֥וֹם הַה֖וּא יְ הוָ֣ה׀ יִרְאֶ֑ה אֲשֶׁר֙ יֵאָמֵ֣ר הַיּ֔וֹם בְּהַ֥ר יְ הוָ֖ה יֵרָאֶֽה׃

Gen 22:14 And Abraham named that site Adonai-yireh, whence the present saying, “On the mount of YHWH there is vision.”[18]

Here the story functions as a hieros logos, that is, an explanation for a holy site; the book of Chronicles (2 Chron 3:1) identifies it with the Temple Mount.[19]

Beth-El—When Jacob is heading to the house of his uncle Laban, he spends the night in an unfamiliar place. That night, in his dream, he sees a stairway with angels of God walking up and down, and he says to himself:

בראשית כח:יז מַה נּוֹרָ֖א הַמָּק֣וֹם הַזֶּ֑ה אֵ֣ין זֶ֗ה כִּ֚י אִם בֵּ֣ית אֱלֹהִ֔ים וְזֶ֖ה שַׁ֥עַר הַשָּׁמָֽיִם׃

Gen 28:17 How awesome is this place! This is none other than the abode of God, and that is the gateway to heaven.

Jacob then names the place Beth-El (house of God) and sets up a pillar, declaring that when God allows him to return safely, he will establish this place as God’s temple. As we know from the book of Kings, Beth-El was an important worship site for the northern kingdom of Israel.[20]

Not a Worship Site

In both the Moriah and Beth-El stories, the encounter of the patriarch with a holy site functions as an etiology for an existing sacred place in Israel.[21] But the Mountain of God never becomes a pilgrimage or worship site, and the burning bush story is not an etiology, but the first act in a drama that leads to a unique, one-time event in Moses’ future and the authors’ past.[22]

Sinai was never meant to be a permanent destination but a waystation for the people to encounter God’s awesome presence as the lawgiver. They lingered at Sinai just long enough to build a portable sanctuary by which they could take that commanding presence with them.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

January 7, 2021

|

Last Updated

February 5, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Rav Rachel Adelman is Associate Professor of Hebrew Bible at Boston’s Hebrew College, where she also received ordination. She holds a Ph.D. in Hebrew Literature from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and is the author of The Return of the Repressed: Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer and the Pseudepigrapha (Brill 2009), based on her dissertation, and The Female Ruse: Women's Deception and Divine Sanction in the Hebrew Bible (Sheffield Phoenix, 2015), written under the auspices of the Women's Studies in Religion Program (WSRP) at Harvard. Adelman is now working on a new book, Daughters in Danger from the Hebrew Bible to Modern Midrash (forthcoming, Sheffield Phoenix Press). When she is not writing books, papers, or divrei Torah, it is poetry that flows from her pen.

Essays on Related Topics: