Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Oldest Known Copy of the Decalogue?

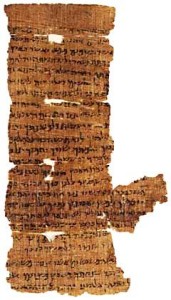

The second of two parchment sheets making up 4Q41 or 4QDeuteronomyn. Wikimedia

Before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran, the oldest Hebrew Bibles were the Aleppo Codex (c. 925 CE) and Leningrad Codex (c. 1009 CE). Although we do not have a complete Bible from the Dead Sea Scrolls, with their discovery at Qumran (1947) and elsewhere, we now have manuscripts a millennium younger than Aleppo and Leningrad. Recently, advanced technology has also enabled researchers to decipher verses from the beginning of Leviticus from a burnt Torah scroll unearthed in 1970 at the ancient Ein Gedi synagogue, dated to the late sixth century C.E. This is the most ancient Torah scroll found since the Dead Sea scrolls and the most ancient ever found in a synagogue.[1]

4QDeutn

Out of 920 scrolls discovered at Qumran, 230 manuscripts belong to what we now call the Hebrew Bible (Tanach). These remains, mostly preserved in fragments, cover parts of all the biblical books, other than Esther. Found among these scroll fragments was a small piece of the book of Deuteronomy, dubbed 4QDeutn (also called 4Q41).[2] Based on the shape of its letters (paleographical dating), 4QDeutn is early Herodian, circa 30-1 BCE.[3]

This text received some publicity lately when it was included among other ancient objects displayed in “A Brief History of Humankind” at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. This scroll was described as “the oldest known copy of the Ten Commandments” in Haaretz, and similar stories appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, etc. But is that title accurate? What is the significance of this text?

Extant Fragments of Deuteronomy

Thirty manuscripts containing parts of the Book of Deuteronomy were preserved at Qumran (among them 2 from Cave 1; 3 from cave 2; 21 from Cave 4, 1 from cave 5; 2 from Cave 7 and 1 from Cave 11)—more than of any other book now part of the Bible. In addition, three manuscripts of that book were discovered eslewehre in the Judean Desert: one in Wadi Murabba‘at, one in Nachal Chever and one at Masada.

All of the non-Qumran texts of Deuteronomy are proto-Masoretic, namely reflecting the consonantal text of MT, or at least, close to the Masoretic text, but some of the Qumran scrolls, such as our scroll (4QDeutn), are non-Masoretic.

The Physical Text

4QDeutn is one of the best preserved fragments from Cave 4 at Qumran. It contains six columns, the first of which is written on a separate sheet of leather, with signs of stitching visible on both edges. [4]

The horizontal dry lines of columns 1-4, and vertical lines and some guide dots in column 1, are still visible. Like all Qumran scrolls, the letters are hung from the line above, rather than written on the line.

The height of the scroll is 7.1 cm., with 12 lines written in every column, with the exception of column 1 which has 8 lines. The scroll is shorter in height than most Qumran scrolls (the average height of a scroll varies from 14 to 25 cm.).[5]

The first 4 columns are complete but only the first, right-hand side remains of the last column. We cannot determine the original size of the sheet, and how many columns it contained.

The parchment was damaged in a number of places before the writing commenced. As a result, these areas were left uninscribed, creating artificial spaces in the middle of the writing.[6] The scroll also contains four corrections, where words or letter were added into the margins.[7]

The Content of the Scroll

Since almost all of the scrolls are very fragmentary, not all the Deuteronomy scrolls preserve the Decalogue, but some, such as 4QDeutj, 4QDeuto, do. Some Exodus scrolls also preserves the Decalogue, albeit only in a small fragment, e.g. in 4QPaleoExodusm, written in Paleo-Hebrew script.

It is impossible to determine whether 4QDeutn was a complete Deuteronomy scroll. The small size of the scroll, and the fact that it contains no text beyond ch. 8, may suggest that 4QDeutn did not contain the entire book of Deuteronomy but only certain chapters (starting in chapter 5), similar to 4QDeutq that was comprised of only the Song of Moses (Deut. 32). It is possible, that 4QDeutn, like 4QDeutj—a poorly preserved text fragment, but which also includes the Decalogue and Shema—was a liturgical text, similar to those quotations found in Tefillin. This text may be associated with the tradition found later in both Talmuds that the Decalogue was recited as part of the liturgy (b. Berachot 12a, j Berachot 1:3).

The Nash Papyrus: An Ancient Mezuzah

Another example of an ancient liturgical text witness to the Decalogue, the Nash Papyrus, came to light half a century before the Dead Sea Scrolls,[8] and is said to have come from the Fayyum in Egypt.[9]Named after its buyer, the Nash Papyrus is a second-century BCE fragment containing the text of the Decalogue followed by the Shema. The manuscript was originally identified as a lectionary used in liturgical contexts, due to the juxtaposition of the Decalogue with the Shema prayer (Deuteronomy 6:4-5), though it may be a liturgical text, or perhaps even a Mezuza.[10]

Another example of an ancient liturgical text witness to the Decalogue, the Nash Papyrus, came to light half a century before the Dead Sea Scrolls,[8] and is said to have come from the Fayyum in Egypt.[9]Named after its buyer, the Nash Papyrus is a second-century BCE fragment containing the text of the Decalogue followed by the Shema. The manuscript was originally identified as a lectionary used in liturgical contexts, due to the juxtaposition of the Decalogue with the Shema prayer (Deuteronomy 6:4-5), though it may be a liturgical text, or perhaps even a Mezuza.[10]

A Harmonistic (Non-Masoretic) Text

When we compare the actual text of Deuteronomy preserved by these early witnesses, they are not identical with the Masoretic text.[11] 4QDeutn resembles the Torah text found in the Samaritan Pentateuch (with the exception of the extra commandment about Mount Gerizim in the Samaritan Pentateuch, probably added by the Samaritans after this version became canonized in their community). Texts such as 4QDeutn are called harmonistic (or proto-Samaritan) texts, namely texts that harmonize two distinct texts by adding, omitting, and/or altering the different word order of the base text under the influence of a parallel text, just like the Samaritan Pentateuch.

Harmonizing the Law of the Sabbath

The following illustrates how the Sabbath commandment in the Decalogue has been harmonized in this text to solve the tension between the two versions of Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5. (See Appendix for a full comparison of the Hebrew texts of the Decalogue in the MT and 4QDeutn.)

Green = Deuteronomy/Deuteronomic Text

Blue = Exodus/Priestly Text

Bold Italics = Adaptation in 4QDeutn (with the exception of spelling differences which I will not note but which the Hebrew reader can see for herself/himself.)

| MT – Exodus | 4QDeutn (4Q41) | MT – Deuteronomy |

|

זָכוֹר אֶת יוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת לְקַדְּשׁוֹ:

|

שמור את יום השבת לקדשו כאשר צוך י-הוה אלוהיך.

|

שָׁמוֹר אֶת יוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת לְקַדְּשׁוֹ כַּאֲשֶׁר צִוְּךָ יְ-הֹוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ:

|

|

שֵׁשֶׁת יָמִים תַּֽעֲבֹד וְעָשִׂיתָ כָּל מְלַאכְתֶּךָ: וְיוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי שַׁבָּת לַי-הֹוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה כָל מְלָאכָה אַתָּה וּבִנְךָ וּבִתֶּךָ עַבְדְּךָ וַאֲמָֽתְךָ וּבְהֶמְתֶּךָ וְגֵרְךָ אֲשֶׁר בִּשְׁעָרֶיךָ:

|

ששת ימים תעבוד ועשית את כול מלאכתך. וביום השביעי שבת לי-הוה אלוהיך. לא תעשה בו כל מלאכה אתה בנך בתך עבדך ואמתך שורך וחמורך ובהמתך גריך אשר בשעריך למען ינוח עבדך ואמתך כמוך.

|

שֵׁשֶׁת יָמִים תַּעֲבֹד וְעָשִׂיתָ כָּל מְלַאכְתֶּךָ: וְיוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי שַׁבָּת לַי-הֹוָה אֱ-לֹהֶיךָ לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה כָל מְלָאכָה אַתָּה וּבִנְךָ וּבִתֶּךָ וְעַבְדְּךָ וַאֲמָתֶךָ וְשׁוֹרְךָ וַחֲמֹֽרְךָ וְכָל בְּהֶמְתֶּךָ וְגֵֽרְךָ אֲשֶׁר בִּשְׁעָרֶיךָ לְמַעַן יָנוּחַ עַבְדְּךָ וַאֲמָתְךָ כָּמוֹךָ:

|

|

וזכרתה כי עבד היית בארץ מצרים ויציאך י-הוה אלוהיך משם ביד חזקה ובזרוע נטויה על כן צוך י-הוה אלוהיך לשמור את יום השבת לקדשו.

|

וְזָכַרְתָּ כִּי עֶבֶד הָיִיתָ בְּאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם וַיֹּצִאֲךָ יְ-הֹוָה אֱ-לֹהֶיךָ מִשָּׁם בְּיָד חֲזָקָה וּבִזְרֹעַ נְטוּיָה עַל כֵּן צִוְּךָ יְ-הֹוָה אֱ-לֹהֶיךָ לַעֲשׂוֹת אֶת יוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת:

|

|

|

כִּי שֵׁשֶׁת יָמִים עָשָׂה יְ-הֹוָה אֶת הַשָּׁמַיִם וְאֶת הָאָרֶץ אֶת הַיָּם וְאֶת כָּל אֲשֶׁר בָּם וַיָּנַח בַּיּוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי עַל־כֵּן בֵּרַךְ יְ-הֹוָה אֶת יוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת וַֽיְקַדְּשֵׁהוּ:

|

כי ששת ימים עשה י-הוה את השמים ואת הארץ את הים וכול אשר בם וינוח ביום השביעי על כן ברך י-הוה את יום השבת לקדשו.

|

|

| Remember the sabbath day and keep it holy. | Observe the sabbath day and keep it holy, as Yhwh your God has commanded you. | Observe the sabbath day and keep it holy, as Yhwh your God has commanded you. |

| Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a sabbath of Yhwh your God: you shall not do any work—you, your son or daughter, your male or female slave, or your cattle, or the stranger who is within your settlements. | Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a sabbath of Yhwh your God; you shall not do any work upon it—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your ox or your ass, or any of your cattle, or the stranger in your settlements, so that your male and female slave may rest as you do. | Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a sabbath of Yhwh your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your ox or your ass, or any of your cattle, or the stranger in your settlements, so that your male and female slave may rest as you do. |

| Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt and Yhwh your God freed you from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm; therefore Yhwh your God has commanded you to keep the Sabbath day and to hallow it. | Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt and Yhwh your God freed you from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm; therefore Yhwh your God has commanded you to observe the Sabbath day. | |

| For in six days Yhwh made heaven and earth and sea, and all that is in them, and He rested on the seventh day; therefore Yhwh blessed the Sabbath day and hallowed it. | For in six days Yhwh made heaven and earth and sea, and all that is in them, and He rested on the seventh day; therefore Yhwh blessed the Sabbath day to hallow it. |

Putting aside the small differences like different spelling or differences in when the conjunctive “and” (waw) is used, the main goal of the harmonistic text of 4QDeutn is to unify the two text-forms of Exodus and Deuteronomy, by including both explanations for Shabbat. The later Midrashic claim of the Rabbis, זכור ושמור בדיבור אחד נאמרו, “‘Remember’ and ‘Observe’ were spoken in a single utterance” (b. Rosh Hashanah 27a),[12] is reflected in the actual text of Deuteronomy here.

Harmonizations are also found when no textual parallels exist, but the text was enriched with details from another text. For example, 4QPaleoExodusm, which based on its script is dated to the end of the second century BCE or the first half of the first century BCE, adds Deut 18:18-19 (the requirement to write the Torah upon stones) after Exodus 20:21 (the prohibition against coveting).[13] Unfortunately, the text of the Decalogue in 4QPaleoExodusm, which is older than 4QDeutn, is very poorly preserved.

The “Oldest” Copy of the Decalogue? An Academic (but not Media-Friendly!) Answer

To return to the question of whether 4QDeutn is the oldest extant copy of the Decalogue, the answer is “no,” “no,” and “depends what you mean.”

- 4QDeutn is not “the oldest known copy of Ten Commandments;” that title must go to the Nash Papyrus.

- It is not the earliest copy of the Decalogue from a Qumran scroll; that title must go to the admittedly fragmentary 4QPaleoExodusm.

- 4QDeutn cannot even be definitively declared the earliest complete copy of the Decalogue from a Torah scroll, since that depends on whether it was indeed a Torah scroll, a Deuteronomy scroll, or more likely, an excerpt used for liturgical purposes.

- None of the above-mentioned early textual witnesses preserves the Masoretic text, all three—4QPaleoExodusm, 4QDeutn, and the Nash Papyrus—are harmonistic texts. There are some Masoretic Qumran texts, but all are slightly later than the above three.

- Most significantly, if the assumption that 4QDeutn is harmonistic is correct, it cannot be the earliest version of the Decalogue—the texts which it harmonized must be earlier, even if no copy of them happens to be extant!

Learning from Ancient Texts

In short, when discussing ancient scrolls, it is important to keep in mind what kind of text it is (Torah scroll, liturgical text, Mezuza, etc.), and to realize that a variety of versions circulated in different types of texts. Understanding this is much more important than knowing which of the randomly preserved texts from antiquity happens to be the earliest.[14]

Appendix

The Decalogue in MT and 4QDeutn

| Masoretic Text (Deut) | 4QDeutn (4Q41)[15] |

|

אָנֹכִי יְ-הֹוָה אֱ-לֹהֶיךָ אֲשֶׁר הוֹצֵאתִיךָ מֵאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם מִבֵּית עֲבָדִים לֹא יִהְיֶה לְךָ אֱלֹהִים אֲחֵרִים עַל פָּנָי:

|

אנכי י-הוה א-לוהיך אשר הוצאתיך מארץ מצרים מבית עבדים לא יהיה לך אלוהים אחרים על פני.

|

|

לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה לְךָ פֶסֶל כָּל תְּמוּנָה אֲשֶׁר בַּשָּׁמַיִם מִמַּעַל וַאֲשֶׁר בָּאָרֶץ מִתָּחַת וַאֲשֶׁר בַּמַּיִם מִתַּחַת לָאָרֶץ: לֹא תִשְׁתַּחֲוֶה לָהֶם וְלֹא תָעָבְדֵם כִּי אָנֹכִי יְ-הֹוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ אֵל קַנָּא פֹּקֵד עֲוֹן אָבוֹת עַל בָּנִים וְעַל שִׁלֵּשִׁים וְעַל רִבֵּעִים לְשֹׂנְאָי: וְעֹשֶׂה חֶסֶד לַאֲלָפִים לְאֹהֲבַי וּלְשֹׁמְרֵי מִצְוֹתָי/ו:

|

לא תעשה לך פסל וכול תמונה אשר בשמים ממעל ואשר בארץ מתחת ואשר במים מתחת לארץ לוא תשתחוה להם ולוא תעבדם כי אנכי י-הוה א-לוהיך אל קנא פוקד עוון אבות על בנים על שלשים ועל רבעים לשנאי עושה חסד לאלפים לאוהבי ולשמרי מצותו/י.

|

|

לֹא תִשָּׂא אֶת שֵׁם יְ-הֹוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ לַשָּׁוְא כִּי לֹא יְנַקֶּה יְ-הֹוָה אֵת אֲשֶׁר יִשָּׂא אֶת שְׁמוֹ לַשָּׁוְא:

|

לא תשא את שם י-הוה א-לוהיך לשוא כי לא ינקה י-הוה את אשר ישא את שמו לשוא.

|

|

שָׁמוֹר אֶת יוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת לְקַדְּשׁוֹ כַּאֲשֶׁר צִוְּךָ יְ-הֹוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ: שֵׁשֶׁת יָמִים תַּעֲבֹד וְעָשִׂיתָ כָּל מְלַאכְתֶּךָ: וְיוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי שַׁבָּת לַי-הֹוָה אֱ-לֹהֶיךָ לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה כָל מְלָאכָה אַתָּה וּבִנְךָ וּבִתֶּךָ וְעַבְדְּךָ וַאֲמָתֶךָ וְשׁוֹרְךָ וַחֲמֹֽרְךָ וְכָל בְּהֶמְתֶּךָ וְגֵֽרְךָ אֲשֶׁר בִּשְׁעָרֶיךָ לְמַעַן יָנוּחַ עַבְדְּךָ וַאֲמָתְךָ כָּמוֹךָ: וְזָכַרְתָּ כִּי עֶבֶד הָיִיתָ בְּאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם וַיֹּצִאֲךָ יְ-הֹוָה אֱ-לֹהֶיךָ מִשָּׁם בְּיָד חֲזָקָה וּבִזְרֹעַ נְטוּיָה עַל כֵּן צִוְּךָ יְ-הֹוָה אֱ-לֹהֶיךָ לַעֲשׂוֹת אֶת יוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת:

|

שמור את יום השבת לקדשו כאשר צוך י-הוה אלוהיך. ששת ימים תעבוד ועשית את כול מלאכתך. וביום השביעי שבת לי-הוה אלוהיך. לא תעשה בו כל מלאכה אתה בנך בתך עבדך ואמתך שורך וחמורך ובהמתך גריך אשר בשעריך למען ינוח עבדך ואמתך כמוך. וזכרתה כי עבד היית בארץ מצרים ויציאך י-הוה אלוהיך משם ביד חזקה ובזרוע נטויה על כן צוך י-הוה אלוהיך לשמור את יום השבת לקדשו. כי ששת ימים עשה י-הוה את השמים ואת הארץ את הים וכול אשר בם וינוח ביום השביעי על כן ברך י-הוה את יום השבת לקדשו.

|

|

כַּבֵּד אֶת אָבִיךָ וְאֶת אִמֶּךָ כַּאֲשֶׁר צִוְּךָ יְ-הֹוָה אֱ-לֹהֶיךָ לְמַעַן יַאֲרִיכֻן יָמֶיךָ וּלְמַעַן יִיטַב לָךְ עַל הָאֲדָמָה אֲשֶׁר יְ-הֹוָה אֱ-לֹהֶיךָ נֹתֵן לָךְ:

|

כבד את אביך ואת אמך כאשר צוך י-הוה א-לוהיך למען יאריכן ימיך ולמען ייטב לך על האדמה אשר י-הוה א-לוהיך נותן לך.

|

|

לֹא תִּרְצָח וְלֹא תִּנְאָף וְלֹא תִּגְנֹב וְלֹא תַעֲנֶה בְרֵעֲךָ עֵד שָׁוְא:

|

לוא תרצח לוא תנאף לוא תגנוב לוא תענה ברעיך עד שוא.

|

|

וְלֹא תַחְמֹד אֵשֶׁת רֵעֶךָ וְלֹא תִתְאַוֶּה בֵּית רֵעֶךָ שָׂדֵהוּ וְעַבְדּוֹ וַאֲמָתוֹ שׁוֹרוֹ וַחֲמֹרוֹ וְכֹל אֲשֶׁר לְרֵעֶךָ:

|

לוא תחמוד אשת רעיך לוא תחמוד בית רעיך שדהו עבדו אמתו שורו חמורו וכול אשר לרעיך.

|

Dedicated to the beloved memory of my late husband, Hanan Eshel, who celebrated his Bar Mitzvah at פרשת ואתחנן.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

July 30, 2015

|

Last Updated

February 8, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Esther Eshel is an Associate Professor in the Bible department at Bar Ilan University, and is the head of the Jeselsohn Epigraphic Center for Jewish History. She holds a Ph.D. in Bible from the Hebrew University. Eshel is a member of the international team publishing the Dead Sea Scrolls and has published 13 scrolls from Cave 4. She is co-author (with J.C. Greenfild and M.E. Stone) of The Aramaic Levi Document.

Essays on Related Topics: