Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Ten Lost Tribes: A Myth to Delegitimize the Samarians

Relief from the Central Palace at Nimrud showing Israelites exiled to Assyria, British Museum. Wikimedia

Stories of the ten lost tribes—whether told by Jews or Christians—only appear after the Second Temple period.[1] Since it began, however, the myths have developed in all sorts of directions, and over the centuries the “lost tribes” have been “found” on every continent except Antarctica.[2] My favorite example is the “Jewish Indian Theory,” first suggested in the 16th century by Spanish explorers who thought that descendants of the ten lost tribes had survived among indigenous Americans; a variant of this theory made its way into Mormon traditions in nineteenth-century United States.

The strangest part of the “ten lost tribes” tradition is that the “ten tribes” of Israel were never lost. True, as we know from Assyrian documents,[3] many Israelites were exiled to Assyria in 720 B.C.E. under Shalmaneser V and Sargon II (as were Judeans under Sennacherib in 701[4]), but many other Israelites continued to inhabit their native homeland in what had become the Assyrian province of Samaria soon after the conquest. Their direct descendants, the Samarians,[5] were still there in the Second Temple period.

Biblical Roots of the Lost-Tribes Tradition and the “Samaritans”

According to the biblical account, after King Solomon dies, the “United Monarchy” splits,[6] with ten tribes becoming the Northern Kingdom of Israel while the tribe of Judah becomes the core of the Southern Kingdom of Judah. The Prophet Ahijah promises Jeroboam that he will rule over ten tribes “torn” from the Solomon’s:

מלכים א יא:לא וַיֹּאמֶר לְיָרָבְעָם קַח לְךָ עֲשָׂרָה קְרָעִים כִּי כֹה אָמַר יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל הִנְנִי קֹרֵעַ אֶת הַמַּמְלָכָה מִיַּד שְׁלֹמֹה וְנָתַתִּי לְךָ אֵת עֲשָׂרָה הַשְּׁבָטִים. יא:לב וְהַשֵּׁבֶט הָאֶחָד יִהְיֶה לּוֹ לְמַעַן עַבְדִּי דָוִד וּלְמַעַן יְרוּשָׁלַ͏ִם הָעִיר אֲשֶׁר בָּחַרְתִּי בָהּ מִכֹּל שִׁבְטֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.

1 Kgs 11:31 He then said to Jeroboam, “Take for yourself ten pieces, for thus says YHWH, the God of Israel: See, I am about to tear the kingdom from the hand of Solomon and will give you ten tribes. 11:32 The one tribe will remain his, for the sake of my servant David and for the sake of Jerusalem, the city that I have chosen out of all the tribes of Israel.[7]

The ten tribes are “lost” when the Assyrians conquer the Northern Kingdom and deport its people:

מלכים ב יז:כג עַד אֲשֶׁר הֵסִיר יְ־הוָה אֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל מֵעַל פָּנָיו כַּאֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר בְּיַד כָּל עֲבָדָיו הַנְּבִיאִים וַיִּגֶל יִשְׂרָאֵל מֵעַל אַדְמָתוֹ אַשּׁוּרָה עַד הַיּוֹם הַזֶּה.

2 Kgs 17:23 In the end, YHWH removed Israel out of his sight, as he had foretold through all his servants the prophets. So Israel was exiled from their own land to Assyria until this day.

The passage goes on to say that the Assyrians settled foreign peoples in what was now the Assyrian province of Samaria:

מלכים ב יז:כד וַיָּבֵא מֶלֶךְ אַשּׁוּר מִבָּבֶל וּמִכּוּתָה וּמֵעַוָּא וּמֵחֲמָת וּסְפַרְוַיִם וַיֹּשֶׁב בְּעָרֵי שֹׁמְרוֹן תַּחַת בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיִּרְשׁוּ אֶת שֹׁמְרוֹן וַיֵּשְׁבוּ בְּעָרֶיהָ.

2 Kgs 17:24 The king of Assyria brought people from Babylon, Cuthah, Avva, Hamath, and Sepharvaim, and placed them in the cities of Samaria in place of the people of Israel; they took possession of Samaria, and settled in its cities.

When they first settle there, YHWH brings lions upon them, since they don’t understand how to worship him properly, so the Assyrian king has an Israelite priest return from exile to teach them the proper way to worship the local deity. Nevertheless, these new people never really adopt Israelite religion fully:

מלכים ב יז:לג אֶת יְ־הוָה הָיוּ יְרֵאִים וְאֶת אֱלֹהֵיהֶם הָיוּ עֹבְדִים כְּמִשְׁפַּט הַגּוֹיִם אֲשֶׁר הִגְלוּ אֹתָם מִשָּׁם. יז:לד עַד הַיּוֹם הַזֶּה הֵם עֹשִׂים כַּמִּשְׁפָּטִים הָרִאשֹׁנִים אֵינָם יְרֵאִים אֶת יְ־הוָה וְאֵינָם עֹשִׂים כְּחֻקֹּתָם וּכְמִשְׁפָּטָם וְכַתּוֹרָה וְכַמִּצְוָה אֲשֶׁר צִוָּה יְ־הוָה אֶת בְּנֵי יַעֲקֹב אֲשֶׁר שָׂם שְׁמוֹ יִשְׂרָאֵל.

2 Kgs 17:33 So they worshiped YHWH but also served their own gods, after the manner of the nations from among whom they had been carried away. 17:34 To this day they continue to practice their former customs. They do not worship YHWH, and they do not follow the statutes or the ordinances or the law or the commandment that YHWH commanded the children of Jacob, whom he named Israel.

The next time we hear the allegation that Samaria is inhabited by non-Israelites with only a dubious claim to authentic YHWH-worship[8] is in Ezra-Nehemiah.[9]

Ezra-Nehemiah Reject the Inhabitants of Samaria as non-Israelite

Ezra-Nehemiah promotes a narrow definition of true Israel, limited exclusively to the Golah “exiles,” referring to the returned Judean exiles. The protagonists of the book even reject what seem to be local Judeans who were never exiled, merely called “the people of the land” (עַמֵּי הָאָ֑רֶץ, Ezra 10:2, 11; Nehemiah 10:30–31), and certainly wrote off the inhabitants of Samaria, the former Northern Kingdom, as transplanted foreigners with no claim to authentic Israelite identity.[10]

When Zerubbabel—a scion of the Davidic line—is rebuilding the Temple, people labeled by the narrator as “adversaries of Judah and Benjamin”[11] ask to participate:

עזרא ד:א וַיִּשְׁמְעוּ צָרֵי יְהוּדָה וּבִנְיָמִן כִּי בְנֵי הַגּוֹלָה בּוֹנִים הֵיכָל לַי־הוָה אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל. ד:ב וַיִּגְּשׁוּ אֶל זְרֻבָּבֶל וְאֶל רָאשֵׁי הָאָבוֹת וַיֹּאמְרוּ לָהֶם נִבְנֶה עִמָּכֶם כִּי כָכֶם נִדְרוֹשׁ לֵאלֹהֵיכֶם (ולא) [וְלוֹ] אֲנַחְנוּ זֹבְחִים מִימֵי אֵסַר חַדֹּן מֶלֶךְ אַשּׁוּר הַמַּעֲלֶה אֹתָנוּ פֹּה.

Ezra 4:1 When the adversaries of Judah and Benjamin heard that the returned exiles were building a temple to YHWH, the God of Israel, 4:2 they approached Zerubbabel and the heads of families and said to them, “Let us build with you, for we worship your God as you do, and we have been sacrificing to him ever since the days of King Esarhaddon of Assyria, who brought us here.”[12]

Note how the narrator undercuts their request to participate with their self-admission of their relatively recent adoption of YHWH worship as well as their non-native Israelite ethnicity. Zerubbabel and Yeshua the high priest reject this request outright, stating that these people are not the same as their people, i.e., they are not Israelites, and YHWH has no interest in their participation:

עזרא ד:ג וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם זְרֻבָּבֶל וְיֵשׁוּעַ וּשְׁאָר רָאשֵׁי הָאָבוֹת לְיִשְׂרָאֵל לֹא לָכֶם וָלָנוּ לִבְנוֹת בַּיִת לֵאלֹהֵינוּ כִּי אֲנַחְנוּ יַחַד נִבְנֶה לַי־הוָה אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל כַּאֲשֶׁר צִוָּנוּ הַמֶּלֶךְ כּוֹרֶשׁ מֶלֶךְ פָּרָס.

Ezra 4:3 But Zerubbabel, Jeshua, and the rest of the heads of families in Israel said to them, “You shall have no part with us in building a house to our God; but we alone will build to YHWH, the God of Israel, as King Cyrus of Persia has commanded us.”

Ezra-Nehemiah’s “adversaries” are never explicitly identified as Samarians, but readers have connected them with Nehemiah’s nemesis, Governor Sanballat of Samaria, who with his allies, obstructed efforts to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem:

נחמיה ג:לג וַיְהִי כַּאֲשֶׁר שָׁמַע סַנְבַלַּט כִּי אֲנַחְנוּ בוֹנִים אֶת הַחוֹמָה וַיִּחַר לוֹ וַיִּכְעַס הַרְבֵּה וַיַּלְעֵג עַל הַיְּהוּדִים. ג:לד וַיֹּאמֶר לִפְנֵי אֶחָיו וְחֵיל שֹׁמְרוֹן וַיֹּאמֶר מָה הַיְּהוּדִים הָאֲמֵלָלִים עֹשִׂים הֲיַעַזְבוּ לָהֶם הֲיִזְבָּחוּ הַיְכַלּוּ בַיּוֹם הַיְחַיּוּ אֶת הָאֲבָנִים מֵעֲרֵמוֹת הֶעָפָר וְהֵמָּה שְׂרוּפוֹת.

Neh 3:33 Now when Sanballat heard that we were building the wall, he was angry and greatly enraged, and he mocked the Jews. 3:34 He said in the presence of his associates and of the army of Samaria, “What are these feeble Jews doing? Will they restore it by themselves? Will they offer sacrifice? Will they finish it in a day? Will they revive the stones out of the heaps of rubbish—burned ones at that?”

The Northern Tribes and an Alternative Perspective on Samaria

The tale in Kings and the attitude of Ezra-Nehemiah paint a portrait of a sharp break between the Judahites in the south and the northern tribes who were exiled in Assyria and replaced with foreigners whose worship of YHWH was syncretistic at best. Add to this the influence of New Testament narratives such as the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:29–37) and the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4:7–42), along with Josephus’ disparaging portrayal of the Samaritans, and it is unsurprising that Jewish and Christian readers assumed that Judah and Jerusalem alone preserved the authentic Yahwistic tradition during the post-exilic Second Temple period.[13]

However, the 1970’s saw the beginning of a break from two thousand years of a (mostly) unquestioned narrative about the so-called “Samaritan schism,”[14] beginning with a careful look at other Second Temple period texts—both biblical and extra-biblical—which contradict the narrow definition of acceptable Israelites and the cultural erasure of the northern tribes in the books of Kings and Ezra-Nehemiah:

Chronicles, written by a Judean in the late Persian or early Hellenistic period, displays a pan-Israelite perspective, taking for granted that the members of the northern tribes are genuine YHWH worshipers.[15] Notably, the account of Hezekiah’s Passover, well after fall of the North to Assyria, repeatedly indicates that Hezekiah (and the narrator) considers the people of the North to be legitimate Yahwists and not newcomers:

דברי הימים ב ל:א וַיִּשְׁלַח יְחִזְקִיָּהוּ עַל כָּל יִשְׂרָאֵל וִיהוּדָה וְגַם אִגְּרוֹת כָּתַב עַל אֶפְרַיִם וּמְנַשֶּׁה לָבוֹא לְבֵית יְ־הוָה בִּירוּשָׁלָ͏ִם לַעֲשׂוֹת פֶּסַח לַי־הוָה אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.

2 Chron 30:1 Hezekiah sent word to all Israel and Judah, and wrote letters also to Ephraim and Manasseh, that they should come to the house of YHWH at Jerusalem, to keep the passover to YHWH the God of Israel.

Hezekiah explicitly addresses the people of the North as the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—not as newcomers! Moreover, he describes them as the remnant who escaped the Assyrian deportation:

דברי הימים ב ל:ו וַיֵּלְכוּ הָרָצִים בָּאִגְּרוֹת מִיַּד הַמֶּלֶךְ וְשָׂרָיו בְּכָל יִשְׂרָאֵל וִיהוּדָה וּכְמִצְוַת הַמֶּלֶךְ לֵאמֹר בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל שׁוּבוּ אֶל יְ־הוָה אֱלֹהֵי אַבְרָהָם יִצְחָק וְיִשְׂרָאֵל וְיָשֹׁב אֶל הַפְּלֵיטָה הַנִּשְׁאֶרֶת לָכֶם מִכַּף מַלְכֵי אַשּׁוּר. ל:ז וְאַל תִּהְיוּ כַּאֲבוֹתֵיכֶם וְכַאֲחֵיכֶם אֲשֶׁר מָעֲלוּ בַּי־הוָה אֱלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵיהֶם וַיִּתְּנֵם לְשַׁמָּה כַּאֲשֶׁר אַתֶּם רֹאִים.

2 Chron 30:6 So couriers went throughout all Israel and Judah with letters from the king and his officials, as the king had commanded, saying, “O people of Israel, return to YHWH, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, so that he may turn again to the remnant of you who have escaped from the hand of the kings of Assyria. 30:7 Do not be like your ancestors and your kindred, who were faithless to YHWH God of their ancestors, so that he made them a desolation, as you see.”

Where Ezra and Nehemiah famously celebrate the divorces imposed on “mixed” marriages between Golah and non-Golah spouses, the Chronicler’s genealogies of the tribe of Judah[16] contain a plethora of mixed marriages involving not just foreigners like Egyptians and Edomites but also members of northern Israelite tribes.[17]

Esther and Mordechai are from the tribe of Benjamin, the tribe of King Saul, the first king of Israel whose family David overthrew.

The Letter of Aristeas is a narrative depiction of the creation of the third-century B.C.E. translation of the Hebrew Torah/Pentateuch into Greek, known as the Septuagint (LXX). As Pamela Barmash of Washington University notes, the narrative takes as given that all twelve tribes exist and are involved in producing the translation:

Six elders from each tribe were sent by the High Priest [in Jerusalem] at Ptolemy's request, and the name of the resulting translation was derived from their total number of seventy-two.[18]

Tobit and his son Tobias, the heroes of the book of Tobit, trace their ancestry to the northern tribe of Naphtali.[19] Set in the period after the Assyrian conquest, the text envisions Israelites maintaining their ancestral traditions despite living in the Persian Diaspora.

2 Maccabees expresses the perception that Judeans and Samarians have a common religious heritage in its outrage (6:2) at the desecration of both the Jerusalem and Gerizim Temples:

2 Macc 6:1 Not long after this, the king sent an Athenian senator to compel the Jews to forsake the laws of their ancestors and no longer to live by the laws of God, 6:2 also to pollute the temple in Jerusalem and to call it the temple of Olympian Zeus and to call the one in Gerizim Zeus-the-Friend-of-Strangers, as the people who live in that place are known.[20]

All of these sources work with the premise that Samarians and Jews are part of the greater Israelite people. The archaeological record shows us that this was not mere imagination, but reflects on the ground realities of the times.

The Archaeological Record and Israelite Samaria

The Assyrians practiced selective deportation, and while some areas of the Northern Kingdom suffered serious demographic decline, archaeological surveys of Northern Kingdom territory also show unbroken continuity of settlement and material culture through the Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, and Hellenistic periods.[21]

On one hand, it is possible that refugees from the Assyrian onslaught would have fled south to Judah where they could have contributed to the a population increase that some scholars identify in the archaeological record of Judah and Jerusalem in the (late) eighth and seventh centuries.[22] On the other hand, as Gary Knoppers (1956–2018) of the University of Notre Dame writes, there is no “evidence that the traditional culture in the Hill Country of Ephraim and Manasseh was suddenly displaced by a single foreign culture or by a variety of foreign cultures.”[23]

In other words, many Israelites, especially non-elites, remained in Samaria and continued to live as such. Indeed, from the Babylonian through the Hellenistic eras, the province of Samaria/Shomron was far richer and more populous than Judea/Yehud, profiting especially from international trade.

The literary record of Judea/Yehud in the Bible and beyond obscures the historical reality of Samaria’s superior socio-economic status which certainly drew Judeans toward mutual engagement for economic, cultural, and arguably, religious benefits.[24] In the Persian Period, when local elites often served as imperial officials, Samarian and Judean religious and political leaders—and their scribal establishments—were surely in communication with one another:

Elephantine Papyri—Indications that Persian-Period Judeans and Samarians were in contact—not conflict—can be seen in a series of letters from the late fifth century that show the Elephantine community, led by a spokesperson named Jedaniah, consulting with officials in both Judea and Samaria over plans to rebuild their temple of YHWH. The longest letter opens with greetings from Jedaniah and Yahwist priests to Bagoas, the Persian-appointed Governor of Judea who, despite his Persian name was probably ethnically Judean and Yahwist:[25]

אל מראנ בגוהי פחת יהוד עבדיכ ידניה וכנותה כהניא זי ביב בירתא

Recto 1 To our lord Bagavahya [Bagoas] governor of Judah, your servants Jedaniah and his colleagues the priests who are in Elephantine the fortress.[26]

Jedaniah describes how local Egyptians destroyed the community’s YHWH temple and then petitions for permission to rebuild it. He complains that a prior letter he and his colleagues had sent about this matter to Governor Bagoas as well as to the Jerusalem priestly establishment and Jerusalem elites had been ignored (Recto 17b-Verso 2a):

אפ קדמת זנה בעדנ זי זא באישתא עביד לנ אגרה שלחנ מראנ ועל יהוחננ כהנא רבא וכנותה כהניא זי בירשלמ ועל אוסתנ ועל זי ענני וחרי יהודיא אגרה חדה לא שלחו עלינ

Moreover, before this - at the time that this evil was done to us - we sent a letter (to) our lord, and to Jehohanan the High Priest and his colleagues the priests who are in Jerusalem, and to Ostanes the brother of Anani and the nobles of the Judeans. They did not send us a single letter.[27]

Later, Jedania informs Gov. Bagoas that the same petition had also been sent to fellow Yahwists in Samaria (Verso 12):

אפ כלא מליא באגרה חדה שלחנ בשמנ על דליה ושלמיה בני סנאבלט פחת שמרינ

Moreover, we sent in our name all the(se) words in one letter to Delaiah and Shelemiah sons of Sanballat governor of Samaria.

The writer takes for granted that as Yahwists, they shared a religious kinship with both Judeans and Samarians and thus looked for support from both.[28]

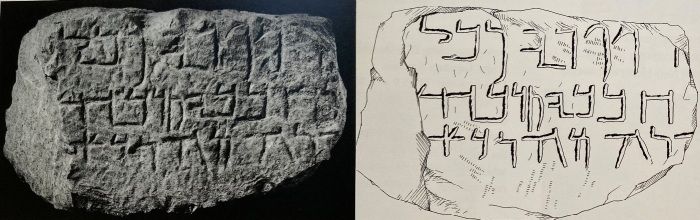

Samaria Papyri and Coins—Individuals mentioned in legal documents of the fourth-century B.C.E. Samaria Papyri use predominantly Yahwistic names—i.e., Delaiah, Yeshayahu, Yehonur, Yehohanan, Mikayahu and the Governor of Samaria, Hananiah—showing that Samarians saw themselves as Israelites.[29] Similarly, contemporary Samarian coins carry traditional “biblical” names like Jeroboam and use paleo-Hebrew script, while their imagery denotes continuity with Iron II Israelite motifs.[30]

Mt. Gerizim Excavations—Yitzhak Magen, Head Archaeological Officer for the Civil Administration of Judea and Samaria, uncovered evidence of a monumental sacred precinct built in the fifth century B.C.E. on Mount Gerizim, already functioning in Nehemiah’s time and in operation until its destruction in 111 B.C.E. by the Hasmonean John Hyrcanus.[31] One of the Hellenistic-era Aramaic inscriptions published by excavator Yitzhak Magen references the Gerizim sanctuary as a “House of Sacrifice,” the same phrase (in Hebrew:בֵית זָבַח) applied in 2 Chronicles 7:12 to the Jerusalem Temple:

ופרינ כל

…and bulls in all…

[דב]ח בבית דבחא

[sacrif]iced in the house of sacrifice

[אז]נא מהורד[א]

????[32]

Gerizim “House of Sacrifice” — from: Magen IAA volume[33]

Gerizim “House of Sacrifice” — from: Magen IAA volume[33]

Hundreds of the fragmentary stone dedicatory inscriptions from the area of Gerizim, dated to the second century B.C.E. and written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, preserve many Yahwistic names.[34] Classic Levitical and priestly names include Levi, Amram, Eleazar, and Phineas (the latter twice in Paleo-Hebrew script). As at Jerusalem’s temple, the Gerizim temple was overseen by Aaronide priests, consistent with the demands of the Torah.[35]

Samarian-Judean intermarriage—Three ancient sources provide a glimpse of North-South intermarriage. According to the book of Nehemiah, a member of the Jerusalem priestly family married a daughter of Sanballat:

נחמיה יג:כח וּמִבְּנֵי יוֹיָדָע בֶּן אֶלְיָשִׁיב הַכֹּהֵן הַגָּדוֹל חָתָן לְסַנְבַלַּט הַחֹרֹנִי וָאַבְרִיחֵהוּ מֵעָלָי. יג:כט זָכְרָה לָהֶם אֱלֹהָי עַל גָּאֳלֵי הַכְּהֻנָּה וּבְרִית הַכְּהֻנָּה וְהַלְוִיִּם. יג:ל וְטִהַרְתִּים מִכָּל נֵכָר וָאַעֲמִידָה מִשְׁמָרוֹת לַכֹּהֲנִים וְלַלְוִיִּם אִישׁ בִּמְלַאכְתּוֹ.

Neh 13:28 One of the sons of Joiada son of the high priest Eliashib was a son-in-law of Sanballat the Horonite; I drove him away from me. 13:29 Remember to their discredit, O my God, how they polluted the priesthood, the covenant of the priests and Levites. 13:30 I purged them of every foreign element, and arranged for the priests and the Levites to work each at his task by shifts.[36]

Similarly, Josephus (Antiquities XI.301ff) tells a remarkably similar story about a marriage in the fourth century between Nikaso, daughter of Sanballat and Manasseh, brother of Jaddua, high priest in Jerusalem. Josephus says that after Manasseh refused to divorce his Samarian wife, Sanballat built the Gerizim shrine for him over which to preside as high priest.[37]

Nehemiah and Josephus alike disparage the Gerizim priesthood as a secondary innovation rooted in the intransigence of a disgruntled Judean priest.[38] Nevertheless, the stories preserve a tradition of elite north-south intermarriage, possibly involving elite priestly families.

The third source for north-south intermarriage is Amherst Papyrus 63, an unprovenanced fourth-century Aramaic document purchased in Egypt.[39] While difficult to decipher,[40] it seems to contain a collection of Aramaic texts associated with a community in Egypt, perhaps Elephantine. Its varied compositions include three psalms, one of which has been identified as a northern Israelite pre-cursor to Psalm 20. It also records a conversation between a king and the apparent spokesman for a newly-arrived group of people who tells the king, “I come from [J]udah, my brother from Samaria has been brought, and now, a man is bringing up my sister from Jerusalem.”[41]

All this evidence has contributed to a new understanding that, as Benedikt Hensel of Karl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg notes:

[I]n postexilic times two independent Yahwistic communities existed within the two provinces Samaria and Judah, each with distinct contours, but sharing a (predominantly) monotheistic Yahwism.[42]

Co-existence rather than conflict seems to have been the norm for Judea and Samaria into the Hellenistic era.[43] As this is the period when the Torah/Pentateuch likely achieved its final form, albeit in a series of stages,[44] many scholars now propose some degree of north-south scribal collaboration or negotiation in its creation.[45]

Composing the Torah: A North-South Enterprise

Emanuel Tov of Hebrew University has shown that most of the supposed edits and expansions contained in the Samaritan Pentateuch (SP) were already present in certain Dead Sea Scroll Torah texts and, as such, are not sectarian Samaritan interpolations.[46] The Masoretic Text and the Samaritan Torah must each be based on variant ancient versions of the Torah; furthermore, the ancient versions were consulted by the Jews of the Dead Sea/Qumran Community.

According to Tov, these ancient precursors to the Samaritan Pentateuch (labelled “pre-Samaritan”) “reflect[s] a popular textual tradition of the Torah that circulated in ancient Israel in the last centuries BCE alongside the MT [Masoretic Text] group and several additional texts.”[47] Tov has further argued that the Samaritan Pentateuch and the Torah text used by the third-century B.C.E. Septuagint translators must derive from a common ancient version of the Torah.[48]

More detailed evidence for co-existence and acceptance of variant Torah versions on the part of religious authorities in Samaria/Gerizim and Jerusalem centers on three Torah passages that until the 21st century had been considered among the most partisan examples of pro-Gerizim Samaritan edits, but turn out to be variants that existed even among Judeans:

1. The Plastered Stones—Deuteronomy commands the Israelites to write the Torah on plastered stones after crossing the Jordan, but the MT and SP disagree about where this is to take place:

דברים כז:ד נה"מ וְהָיָה בְּעָבְרְכֶם אֶת הַיַּרְדֵּן תָּקִימוּ אֶת הָאֲבָנִים הָאֵלֶּה אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי מְצַוֶּה אֶתְכֶם הַיּוֹם בְּהַר עֵיבָל [נ"ש: בהרגריזים] וְשַׂדְתָּ אוֹתָם בַּשִּׂיד.

Deut 27:4 [MT] So when you have crossed over the Jordan, you shall set up these stones, about which I am commanding you today, on Mount Ebal [SP: Mount Gerizim] and plaster them with plaster.[49]

Papyrus Giessen, the oldest LXX manuscript for this passage, reads Gerizim like the SP, and this is what appears in the Vetus Latina (Old Latin) translation.[50] This indicates that the Hebrew Torah from which the translators worked read “Gerizim,” and consequently, the Jewish translators in Alexandria did not consider it troubling.[51]

That Gerizim, not Ebal, should be the original name also has narrative logic. According to all versions of Deuteronomy, Gerizim is the mountain designated for blessing while Ebal is the one designated for cursing, making it an unlikely site for stones engraved with the Torah (Deut 27:12–13).[52]

2. The Place YHWH Chose or Will Choose—Deuteronomy’s centralization of worship formula differs: MT has the imperfect הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר יִבְחַר “the place He will choose” in the future, allowing for Jerusalem. SP uses the perfect המקום אשר בחר “the place He has chosen,” indicating Mount Gerizim, the only place chosen in the Torah (see above). Notably, LXX, Old Latin, Boharic, and Coptic are witnesses to the past tense, “has chosen,”[53] and it is unlikely that Christian translators (Old Latin, Boharic, Coptic) would have known or wanted to consult the Samaritan Pentateuch. The two different verb tenses appear to originate in different early versions of the Torah.

3. Tenth Commandment—The so-called “Samaritan Tenth Commandment” is an expanded passage after Exodus 20:17 that is composed exclusively of quotations from Deuteronomy. Recently Hila Dayfani of Hebrew University has argued that the entire pre-Samaritan text was present at Qumran in a large but fragmentary manuscript, 4QpaleoExodm.[54] After a “material and textual reconstruction of the relevant columns in 4QpaleoExodmusing digital tools that simulate the condition of these columns before the scroll’s deterioration”[55] she demonstrated that “there is room for all three major expansions of SP Exod 20 in the original scroll.”[56]

It seems, therefore, that the Samaritan Pentateuch actually began as a shared text between Judeans and Samarians.[57] These textual discoveries are indicative of what Stefan Schorch of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem calls the “joint Israelite Hebrew literary culture,”[58] and demonstrate Gary Knoppers’ contention that the Pentateuch should be “regarded as a common patrimony of the time before the relations between the Judeans and the Samarians became seriously aggrieved in the last two centuries BCE. ”[59] It is worth remembering that at the time the Pentateuch was approaching its final form, there were fully operative YHWH sanctuaries at both Jerusalem and Gerizim (not to mention at Elephantine and perhaps other Diaspora sites), each with its dedicated complement of priests and scribes.[60]

Connected Communities

It is time to abandon the notion that following 720 B.C.E., the population of the former Northern Kingdom played only a marginal role in the development of the YHWH traditions that are the basis of Judaism.[61] We now know that the split between Jews and Samarians occurred centuries after the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, aggravated by the Hasmonean conquest of the north in 111 B.C.E.[62]

The opponents of the returnees in Ezra and Nehemiah were likely fellow YHWH worshipers who included both non-Golah Judeans claiming their own stake in local governance, and Samarian descendants of the northern tribes of Israel, living and worshiping God in their ancestral homeland—who, no doubt, would have been surprised to hear they were “lost.” Far from vanishing into the mists of legend, the so-called “Ten Lost Tribes” were neither lost nor marginal to Israelite history. The story turns out to be not one of disappearance, but of continuity and contribution.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

August 13, 2025

|

Last Updated

February 9, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Mary-Joan Leith is Professor of Religious Studies at Stonehill College. She holds an M.A. and Ph.D. from Harvard University and has participated in numerous archaeological excavations around the Mediterranean and the Levant. She is the author of Greek and Persian Images in Pre-Alexandrine Samaria: The Wadi Ed-Daliyeh Seal Impressions (1990); Wadi Daliyah I: The Wadi Daliyeh Seal Impressions: Discoveries in the Judean Desert 24 (Clarendon Press, 1998); Seals and Coins in Persian Period Samaria (2000); and The Virgin Mary: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2021).

Essays on Related Topics: