Op-ed

Academic Biblical Studies, the 71st Face of the Torah

The need for rational-critical approaches to Scripture, in the popular Israeli discussions of the weekly parasha.

Pixabay adapted

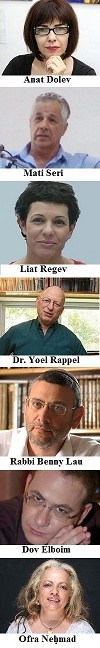

Every weekend, public radio and television inundate us with discussions of the weekly Torah portion. On Thursdays, Anat Dolev introduces a rabbi from Ma’aleh Adumim (who speaks about Kabbalah); on the Television program ‘Erev Chadash, Mati Seri speaks about the parasha; on Friday at noon, on the Reshet Bet radio program,  Liat Regev introduces Dr. Rachel Goldberg (more Kabbalah); then in the afternoon, on Network B (Reshet Beth), we have Dr. Yoel Rappel, and on Channel 1, Rabbi Benny Lau; in the evening, Dov Elboim,is also on Channel 1; on Saturday night, we have another showing of Elboim’s program, and on Reshet Beth we have Ofra Neḥmad; and there are surely many other “weekly parasha” programs on secular media. Aside from these, there are, of course, dozens of features about the weekly parasha in the religious media – newspapers, pamphlets, and radio stations.

Liat Regev introduces Dr. Rachel Goldberg (more Kabbalah); then in the afternoon, on Network B (Reshet Beth), we have Dr. Yoel Rappel, and on Channel 1, Rabbi Benny Lau; in the evening, Dov Elboim,is also on Channel 1; on Saturday night, we have another showing of Elboim’s program, and on Reshet Beth we have Ofra Neḥmad; and there are surely many other “weekly parasha” programs on secular media. Aside from these, there are, of course, dozens of features about the weekly parasha in the religious media – newspapers, pamphlets, and radio stations.

The common factor in all these programs, notwithstanding that some of them are quite interesting, and some invite stimulating speakers to participate, is not that they all reflect a religious, or just a ‘traditional’ outlook, but that they all reflect an essentialist, midrashic approach to the parasha. The point of departure of this method of reading is the readers’ subjective truth, which they proceed to insert into the holy text, thus giving their message divine authority. This is the genre known as “derasha”, homiletics, which has been known for generations.

There is nothing wrong with the homiletic approach. On the contrary: the midrashim of the Talmudic rabbis, the Zohar, the musar literature, and the traditional commentaries on the Torah contain many precious gems, excellent analogies, and inspiring moral lessons. The problem is that the media presents this approach as the one and only approach to the biblical text.[1] The problem is that the exclusive focus on the homiletical approach excludes the peshat method of interpretation, the method used by traditional commentators such as Rashi, Rashbam and ibn Ezra, and whose modern day practitioners, critical Bible scholars, have taken in new and exciting directions.

A child, an adolescent, or an adult in Israel, whose exposure to the Torah (and to the Bible as a whole) is through the media, will get the impression that rational thought and biblical interpretation are opposites. The media promulgates the incorrect belief that the only possible approach to the Torah is that this is a divine book, which conceals much more than it reveals, and, therefore, there is no point in trying to understand it in a rational way.

This gives the impression that it is impossible to discuss the weekly parasha without using terms such as shoresh ha-neshama (“the source of one’s soul”), ha-nitzotz ha-’eloqi “the divine spark”, or netzacḥ yisra’el (“the eternal victor of Israel”, an obscure term for God taken from I Samuel 15:29); or without using folk etymologies, such as that the name yisra’el[Israel] is an anagram of li rosh [“I have a head”]; or ma’avaq [a struggle] is an allusion to avaq [dust].[2] All this discourse completely leaves out the possibilities presented by critical Bible scholars, who strive to understand the Torah as a human work – that is, a book written by flesh-and-blood people over a slow process of hundreds of years.

In addition to the above-described method of study, which attempts to solve apparent contradictions, (which are, by definition, impossible to resolve by logical methods,) by forcefully rereading texts against their grain, it should be acceptable to present a different way of looking at the text. In other words, the public should be allowed to ponder the question of how we can explain the very existence of all these contradictions in the parasha. Critical Bible scholars have an answer to this question, namely that since the Torah is a book written by many people, coming from a variety of outlooks and traditions, over a long process of formation and transmission, some contradictions are to be expected.

The exclusion of the scholarly, critical, scientific method from discussions of the weekly parasha comes at a high cost: not only does it lead to a one-dimensional understanding of the Torah, but it also produces superficial, irrational models of thought, and encourages superstitions.

Excluding the scholarly-critical approach from “discussions of the weekly parasha” is an important pillar, albeit possibly concealed, in enabling an Israeli society that treats the Bible as the exclusive property of those that view it as solely a divine book. According to this approach, anyone that does not think in accordance with traditional religious models can have no connection to the Bible, the most important treasure of Jewish culture.

Subconsciously, this exclusion of critical methodologies contributes to an intolerant society, a society that is unwilling to open a window to secular or rational approaches to any field associated with Judaism. Against this exclusivist background, it is easy to make separate lines for men and women, insist on modest clothing in public, forbid women from singing, and more.

Let me reiterate that I have no problem with any of the specific programs on the weekly parasha that currently exist on the media; my problem is with the sum total of them. It is obvious why there is no critical-scientific approach to Scripture in the religious media (TheTorah.com may be beginning to change that) but why is this so also in the secular media? The answer is not that the people running secular media are ignorant or unaware; no. Unfortunately, the reason is based on the same impulses that allow separate lines for men and women, removal of pictures of women from the public street, and other such things – namely, fear, anxiety, or perhaps just convenience of avoiding confrontation. “Why should we start up with them? Why should we get them upset? Wouldn’t it be a shame if we would lose some readers, distributers, listeners, or viewers?”

I understand the fear, but I fervently believe that the price that society as a whole pays for the exclusion of critical-rational approaches from public discussions of the weekly parasha is far too high for us to allow concerns of convenience or financial gain to determine our decision.

Just recently, Prof. Dan Schechtman, the recent winner of the Nobel Prize for chemistry, spoke about the need to educate people in tolerance and in rational thought. This is what science, including academic biblical studies, teaches. The exclusion of the science of Bible scholarship from Israeli secular culture is a litmus test for measuring the level of tolerance and rationality in this culture.

In order to maintain a “Jewish and democratic state” for the future, we will need to develop a “Jewish and rational culture” as part of it – and there is no better medium for this than bringing academic biblical studies into our cultural discourse.

The midrash that speaks of the “seventy faces of the Torah” was not aware of biblical criticism, the 71st face of the Torah. The cultural agents that run Israeli media are aware of this face of the Torah, and the responsibility lies on them to give it an appropriate place in creating the image of Judaism in Israel.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Footnotes

Prof. Yair Hoffman, z”l, was Professor at Tel Aviv University’s Department of Bible, where he chaired the department. He was the head of the Chaim Rosenberg School for Jewish Studies and also the Chairman of the Bible Department at Seminar Hakibuzim College. Hoffman received his Ph.D. from Tel Aviv University, was the author of The Doctrine of the Exodus, A Blemished Perfection: The Book of Job in Context, and Jeremiah, A Commentary vol. 1-2, and was the editor of the journal, Beit Mikra.