Interview

A Religious Archaeologist: Ten Questions with Dr. Hayah Katz

On Pottery, Religious Faith, and the Challenges for Women in Archaeology

Dr. Hayah Katz is a teaching faculty member in the Dept. of History, Philosophy and Judaic Studies at The Open University of Israel. Her main area of expertise is the study of the economy of the First Temple period. Apart from several articles on this subject, she published a comprehensive study, A Land of Corn and Wine … a Land of Olive-Trees and of Honey: The Economy of Judah Kingdom in the First Temple Period (Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi Press 2008, [Hebrew].) Dr. Katz also writes on the history of Israeli archeology, and published a biography of Prof. Ruth Amiran, a turn of the (20th) century pioneer in the field of Near Eastern archaeology (Pardes Press, 2012, [Hebrew].) Her present study deals with the attitude of Jews and Christians to the archaeology of the Land of Israel.She is a member of the Tel ‘Eton expedition team as an associate director and responsible for pottery analysis.

1. You wrote an article about mikvah, “Biblical Purification: Was it Immersion?” (TheTorah 2014), with a surprising conclusion. What brought you to study this subject?

.jpg?alt=media&token=4bce5137-5ce5-46ef-bec4-fa4e010ab800)

Generally, I study things that interest me personally, things that affect my life. That is what inspired my research into purification and mikvah in biblical times. Mikvah is a central ritual in the life of any religious Jewish woman, during the childbearing years, and I became curious as to whether what we do now at all resembles what Israelites practiced in biblical times.

When I began researching the question, I already knew that there was no archaeological evidence for ritual baths in the biblical period; these came into use during the Second Temple period. I also knew that the Torah never uses the word טבילה (immersing) when discussing purification, only רחיצה (washing). So I was curious, if they didn’t immerse in mikvaot during the biblical period, what did they do for purification? How did the ritual work?

2. How did you get interested in becoming a field archaeologist?

.jpg?alt=media&token=4d7bb0d9-a108-4dfc-81c5-252df9b634ce)

When I started college, I wasn’t planning to become an archaeologist, but to be a historian. Specifically, I loved modern history. But I also took courses in archaeology and I just fell in love with it. At the time, I was working with David Ussishkin in Lachish, and I became a student of his, which is what brought me to Iron Age archaeology, i.e. the archaeology of the biblical period. From Ussishkin I learned how to be a field archaeologist, and what it means to work well in the field. I’ve continued to dig ever since, at Beit Shemesh (where I met Avi Faust, with whom I work now), in Jezreel, in Tel Zaytun, and now in Tel Eton.

3. How did you handle being a field archaeologist when you were raising your children?

That was actually quite difficult. In the end, I didn’t dig often when I had small kids and when I did, I tried to be creative about it. When I dug in Tel Safi, I brought a nanny. (I think I may be the only archaeologist to have done this.) I also tried getting involved in a dig near my house, at Tel Zaytun in Kiryat Herzog, a neighborhood in Bnei Brak. We used to have staff meetings at my house, and I paid my daughters’ friends in popsicles to come by in the afternoons and help wash the pottery out on the grass outside.

4. Is being a religious Jew and a biblical archaeologist a difficult balance?

That is a tough question. First, being religious is part of my identity. I keep halacha, unconnected to the findings of Iron Age archaeology. My observance comes from my personal acceptance of Torah and mitzvot, as understood by Rabbinic Jews; that is my faith or faithfulness to tradition. I am aware that halacha came together in the Second Temple period, and that is what my religion is: the Judaism of the Rabbis and the Talmud.

As a scholar, though, I do not allow my faithfulness to tradition to cloud my judgment about history. The questions of what was or wasn’t, I don’t always know, but I try to base my scholarly positions on the archaeological record, as I did with the purity study. And purity laws are hardly the only example of tension between Rabbinic Judaism and the Torah; if you check halacha against the Bible it is very different.

5. Can you give an example of when you feel the tension?

Listening to Devarim being read in shul. I go to shul every Shabbat and listen to the Torah reading. Somehow, when hearing Devarim read, I can’t help but hear the (seventh century BCE) Assyrian vassal treaty parallels that are so stark once you learn about them. As a historian, it is very clear to me that the Bible is firmly planted in Near Eastern culture, and the text reflects this in various ways. It isn’t the way I was brought up to think about the Torah, or how I relate to it religiously, but there it is.

I know there are people who say that it doesn’t matter to them that many of the biblical stories are fake, or that the Torah was written down and edited over a period of time, and completed centuries later than the purported events. Nevertheless, I have to admit that it bothers me when I think about it. It doesn’t change my lifestyle or my attachment to my religious identity, but things would certainly be easier if the stories in the Torah turned out to be historical or the laws overlapped more significantly with what we practice now.

6. Do you have any solutions to the contradictions between what the Bible says and the historical or archaeological record?

Not really. I refuse to try all the classic answers that don’t work. Instead, I live in two worlds and do my best. In fact, it wouldn’t be true to myself to have clear answers; it would be more like trying to trick myself, which is a counterproductive enterprise.

In the end, as difficult as it is, I try to follow Berl Katznelson’s advice in his 1940 speech “בזכות המבוכה ובגנות הטיח” [Better Perplexed than Whitewashed]:

אל נהיה פועלי־רמייה לא במעשה ולא במחשבה. אל יהיה חלקנו עם טחי טיח.

Let us not be unscrupulous workers, neither in deed nor in thought. Let us not not cast our lot with the white-washers.

7. Do your students ask you for help or advice on their own religious questions?

It comes up every year with students. Most of them want the black and white answers. Did a certain event happen or not? Is the Torah “true” or “false”? It is important for them to know that it is not so simple. Personally, I believe that the Bible contains historical nuggets but what is history, what is embellishment and what is myth, is hard to know.

Many rabbis warn students away from going to college, and especially from taking any classes (like mine) that could pose any problems with a person’s simple faith. I actually understand why these rabbis are against students going to college, although I don’t agree, obviously. Once these students are exposed to academic scholarship, even at its most basic, they will start to think for themselves.

When I was in college, although I was interested in Iron Age archaeology, I actually avoided courses on Bible or things that would shake up my thinking about the unity of the Torah. Now that I am older, I regret this decision, since there is much that is quite interesting in academic biblical studies, and there is much more I could have learned had I taken the opportunity, but I was afraid.

8. You are also a ceramics expert. What is a ceramics expert and how did you choose this area of study?

The study of ceramics refers to the study of the forms of pottery used during various periods and in different places. It is one of the main ways that archaeologists date sites. Since we have a good sense of the pottery sequence, if we find pottery found in situ, we can date the occupation layer of this site in which the pottery is found with relatively good accuracy.

Focusing on ceramics and pottery is actually quite common for female Israeli archaeologists, although it is becoming less so. This is not a coincidence in my opinion. The reasons for the large number of women specializing in ceramics, in my opinion, are many. Firstly, many women simply chose this route. There are multiple factors that lead to this. Studying pottery is significantly easier physically than field work, which is quite strenuous. Also, it is also difficult for women with young children to do fieldwork. A third reason might be since it requires attention to very small details. In general, I believe you will find that female archaeologists publish an inordinate amount of studies, dealing with small finds and details.

Nevertheless, the inverse is important to note as well, i.e. that women were pushed into this line of work. The reason for this push, sadly, is because in the hierarchy of archaeologists, those who specialize in pottery are considered to be lower on the totem pole than field archaeologists, especially the coveted position of those who run their own digs. Not to sound too cynical, but there is a “back to the kitchen” aspect to this, even if the men are not conscious of this.

9. You wrote a book about Ruth Amiran? Why the focus on her work?

Although Iron Age archaeology became my primary focus, I was able to combine this with my interest in modern history, which was the focus of my B.A. work, by studying the history of archaeology, and I continue to be interested in this.

Although Iron Age archaeology became my primary focus, I was able to combine this with my interest in modern history, which was the focus of my B.A. work, by studying the history of archaeology, and I continue to be interested in this.

As I became more interested in ceramic studies, I came into contact with the work of Ruth Amiran (1914-2005). Amiran is really the mother of ceramic studies in Israel. Her book has remained the main textbook for early ceramics fifty years running.[1]

It was around this time that I also began to think about the point I discussed earlier, why women were so dominant in this particular niche of archaeology. I decided that I wanted to study Ruth Amiran as a test case for understanding the place of women in Israeli archaeology.

As I began to study her more, I became quite taken with the project. Ruth was quite a special person as well as an important scholar. It is also worth noting that she never had children, which was a significant factor to take into account when evaluating both her personal life and her academic career.

In researching for my book, I didn’t only read her academic work, but I read much of her personal writing, including a collection of love letters. Her niece was left in charge of her materials after her passing. It took me a while to get the niece to work with me, but eventually she understood the project and got behind it, which gave me unbelievable access to Amiran’s personal life. It felt quite voyeuristic at times, and this was academic work not hagiography, but I feel that the project ended up as quite a success.

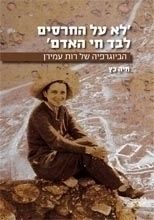

The book was published in Hebrew, and I called it Not on Ceramics Alone can a man Live. The title plays off Deuteronomy 8:3, of course, but I got it from a dedication Ruth’s husband, Prof. David Amiran, wrote to her in a book he bought her as a present. The dedication reads:

לא על החרסים לבד חי האדם אלא גם על הלחם, מדוד שלך לנצח

Not on ceramics alone can a man live, but also on bread. From your David, forever.

I am quite certain that this was also meant as a lover’s humorous barb, highlighting the fact that Ruth was far from the classic “homemaker,” leaving much of that work to David.

10. What other subjects do you focus on?

Insofar as Iron Age archaeology, I am particularly interested in the economics of the period. The economics of Ancient Judah was the subject of my M.A studies at Tel Aviv University as well as my doctorate at Bar Ilan University (under Zev Safrai and Shmuel Vargon). I published my findings as a book called, Land of Grain and Wine—Land of Olive Oil and Honey [Hebrew].

Insofar as modern archaeological trends, one thing that has caught my interest recently is the relationship between Israelis and archaeology. When you look back at the years between 1948 and 1967, the Religious Zionist camp expressed little or no interest in archaeology. This stands out as particularly surprising when compared with religious Christians, who were always interested, going back to the turn of the century, and secular Zionists, who were dominant in the field between ‘48 and ‘67.

There were literally thousands of Israelis doing archaeology in those years, but virtually no religious people were involved. I think this was because, at that time, even among the Religious Zionists, there was little interest in the study of Tanach, which is one of the main entry points for many into the archaeology of Israel. In addition, interest in archaeology is often built on a connection to the land, and the religious Zionists weren’t attached to the land in the same way as the secular Zionists were. Perhaps they connected to the land mystically, but not physically.

This changed after 1967. The Religious Zionists became very attached to the study of Tanach and much of their yeshiva curriculum nowadays focuses on Tanach study. Second, they developed an attachment to the Land of Israel in a very physical way. This physical attachment to the land its incorporation into the study of Tanakh (hence the interest in archaeology) is key for this group, which is part of what fuels the settler movement and the ideology of “the land of Israel in its entirety” (ארץ ישראל השלימה). At the same time, secular Israelis have become much less Zionist, and interest in archaeology among this group has lessoned accordingly.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Footnotes

Dr. Hayah Katz is a Senior Lecturer of Iron Age Archaeology at the Department of Land of Israel Studies in Kinneret College on the Sea of Galilee. She holds an M.A. in archaeology from Tel Aviv University, and a Ph.D. in archaeology from Bar-Ilan University. Her research focus is the history of archaeological research in the Land of Israel from the 1920s until modern times. In a desire to develop this field she founded a Chair named after Zev Vilnay in the Department of the Land of Israel Studies. In addition, she is director of the Meron Ridges Project and the Tel Rosh excavations, focusing on a comprehensive study of settlement processes in the Upper Galilee region during the first millennium B.C.E.