Edit article

Edit articleSeries

39 Melachot of Shabbat: What Is the Function of This List?

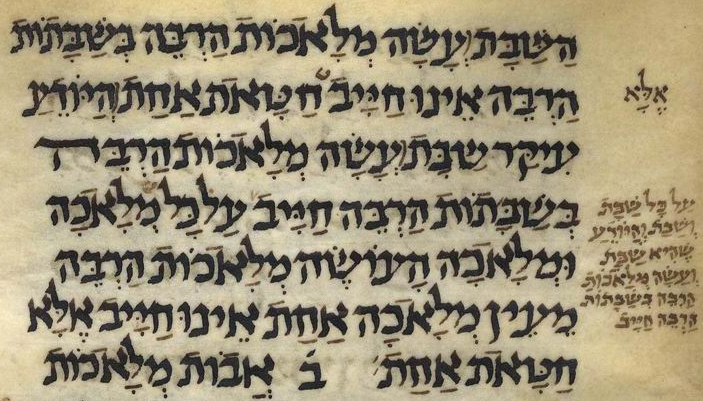

Mishna Shabbat, MS Kaufmann A50, Italy, Late 11th to mid-12th c., ff. 44v-45r.

The 39 Labors and Mishnah Shabbat

Halakhic treatments of the laws of Shabbat take for granted that the forbidden labors can be divided into 39 primary types.[1] There is a good basis for this—Mishnah Shabbat 7:2 says exactly that:

אבות מלאכות ארבעים חסר אחת...

The primary categories of prohibited labors are forty minus one:

הזורע והחורש והקוצר והמעמר הדש והזורה הבורר הטוחן והמרקד והלש והאופה (1-11)

(1) sowing, (2) plowing, (3) harvesting, (4) binding sheaves, (5) threshing, (6) winnowing, (7) selecting, (8) grinding, (9) sifting, (10) kneading, (11) baking;

הגוזז את הצמר המלבנו והמנפצו והצובעו והטווה והמיסך והעושה שתי בתי נירין והאורג שני חוטין והפוצע ב' חוטין הקושר והמתיר והתופר שתי תפירות הקורע ע"מ לתפור שתי תפירות (12-24)

(12) shearing wool, (13) bleaching it, (14) hackling it, (15) dyeing it, (16) spinning, (17) stretching the threads, (18) making two meshes, (19) weaving two threads, (20) dividing two threads, (21) tying, (22) untying, (23) sewing two stitches, (24) tearing in order to sew two stitches;

הצד צבי השוחטו והמפשיטו המולחו והמעבד את עורו והמוחקו והמחתכו (25-31)

(25) hunting a deer, (26) slaughtering it, (27) flaying it, (28) salting it, (29) curing its hide, (30) scraping it, (31) slicing it,

הכותב שתי אותיות והמוחק על מנת לכתוב שתי אותיות (32-33)

(32) writing two letters, (33) erasing in order to write two letters;

הבונה והסותר (34-35)

(34) building, (35) pulling down;

המכבה והמבעיר (36-37)

(36) extinguishing, (37) kindling;

המכה בפטיש (38)

(38) striking with a hammer;

המוציא מרשות לרשות (39)

(39) taking out from one domain to another.[2]

The discussion of forbidden labors in the rest of the Mishnah, however, seems to ignore this list, as we can see from the following points:

- Out-of-order follow up—Generally, when a Mishnah presents a list and a subsequent Mishnah comments on it, the items are discussed in the same order in which they first appeared.[3] The following mishnayot in tractate Shabbat, however, first discuss the last item (#39), then move on to building (#34) and then to plowing (#2).

- Uneven follow up—Following the list in 7:2, the Mishnah spends four chapters explaining the prohibition of “taking from one domain to another” (#39) in detail, then only deals with a handful of other forbidden labors very briefly.

- Missing activities—Activities which the Mishnah itself forbids in earlier chapters, such as cooking (3:1 ff.) and laundering (1:8,9), do not appear on this list.

Mishnah 7:2—A Supplement

Yitzhak Gilat (1919–1997), the late professor of Talmud from Bar Ilan University, already noted a number of these difficulties.[4] His solution is that mishnah 7:2, the list of 39 forbidden labors, is a later addition to the Mishnah. In fact, the flow from mishnah 7:1 to 7:3 is quite smooth, and the insertion of the list interrupts the flow:

ז:א כלל גדול אמרו בשבת...

7:1 A general rule did they state concerning Shabbat…

ז:ב אבות מלאכות ארבעים חסר אחת...

7:2 The primary prohibited labors are forty minus one…

ז:ג עוד כלל אחר אמרו...

7:3 And a further general rule did they state…

Gilat’s observation begs the question, why was the list added?

Theory 1 (Gilat): Added to Explain the Obscure Term אב מלאכה

Gilat suggests that 7:2 was inserted to explain the words אב מלאכה “primary labor” found in mishnah 7:1. This vague term does not appear anywhere else in the Mishnah.

היודע שהוא שבת ועשה מלאכות הרבה בשבתות הרבה חייב על כל אב מלאכה ומלאכה.

He who knows that it is Shabbat and performed many acts of labor on many different Shabbats is liable for the violation of each and every primary category of labor.

A later editor, realizing that the term “primary category of labor” (אב מלאכה) was unclear, added a list of such primary categories of labor, likely from another source, to clarify what a primary category is. For instance, if a person were to go hunting, light a fire, and dye wool—three of the 39 primary labors listed in m7:2—on three consecutive Shabbats, he or she would be cumulatively liable for nine separate violations of the prohibition of doing labor on Shabbat.

“Primary” Is a Late Supplement: The Manuscript Evidence

However, this solution is not satisfactory. As already noted by Gilat, the word “primary category” (אב) does not actually appear in the Kaufmann Manuscript of the Mishnah, our best manuscript.[5]

The word is also missing in a number of other early text witnesses, and thus, seems to be a later addition.[6] Therefore, this second mishnah, while a supplement, cannot be an explication of the term אב מלאכה in the first. In fact, the revision of the mishnah seems to have developed in the opposite direction to that suggested by Gilat, that the term אב was added to mishnah 1 because of mishnah 2.

Why אב Was Added to Mishnah 1: A Ripple Effect from Mishnah 2

The opening mishnah of chapter seven lays out three scenarios of a person unintentionally[7] violating Shabbat:

1. One Who Doesn’t Know What Shabbat Is

כל השוכח עיקר שבת ועשה מלאכות הרבה בשבתות הרבה אינו חייב אלא חטאת אחת

Whoever forgets the basic principle of Shabbat and performed many acts of labor on many different Shabbats is liable only for a single chatat (sin or purification offering).

A person who does not remember that the commandment of Shabbat exists, even if he did many prohibited labors on many Shabbats, is liable for only one sin offering in total.

2. One Who Didn’t Know It Was Shabbat

היודע עיקר שבת ועשה מלאכות הרבה בשבתות הרבה חייב על כל שבת ושבת.

He who knows the principle of Shabbat and performed many acts of labor on many different Shabbats is liable for the violation of each and every Shabbat.

Here, the Mishnah is slightly stricter, obligating the person in a sin offering for each Shabbat, though not for each act of labor.

3. One Who Violates Shabbat Absent-mindedly

היודע שהוא שבת ועשה מלאכות הרבה בשבתות הרבה חייב על כל (אב) מלאכה ומלאכה

He who knows that it is Shabbat and performed many acts of labor on many different Shabbats is liable for the violation of each and every (primary category of) labor.

Prior to the addition of the word אב, the third section obligates a person in a sin offering for every act of labor on every Shabbat. The addition of the word אב into this third section softens the blow somewhat, since now the person is not obligated for every single violation of the Shabbat, but only for every category of act violated. Now, if he performed two acts of labor that were part of the same category on a given Shabbat, he would only need to bring one sin-offering for this.

In short, 7:2 could not have been added to explain the meaning of this word in 7:1, since it wasn’t there. Instead, the revision of the first mishnah was likely influenced by the terminology in the second mishnah, with its concept of primary labors.

We are accordingly left with the original question: Why was the second mishnah added? To answer this question, we need to understand the nature of the list.

An Inexplicable List

Mishnah Shabbat 7:2 opens by declaring this to be a list of 39 primary categories of labor, and it ends with this same framing:

הרי אלו אבות מלאכות ארבעים חסר אחת.

These, then, are the primary prohibited labors: forty minus one.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to understand the choice of these 39 acts as an attempt to fully portray all the primary categories of labor. In what way are the 39 labors “primary”? Why should cooking be less of a primary labor than baking,[8] or why is laundering less of a primary labor than bleaching?

In fact, some of the activities seem so similar that it is difficult to say why they represent separate categories at all. Even sages in the gemara admit to not knowing the difference between zoreh (#6, winnowing), borer (#7, selecting), and meraqed (#9, sifting).[9] Moreover, Mishnah Shabbat 12:2 prohibits plucking, trimming, and cutting, which are not part of the list, and prescribes the same punishment as it does for plowing (liability for a sin offering), which is part of the list. In short, this list of primary forbidden labors is neither comprehensive nor clear.

Theory 2 (Hauptman): Added to Explain the Obscure Phrase מעין מלאכה אחת

In my view, Mishnah Shabbat 7:2 is explaining the fourth and final case[10] of the previous mishnah (7:1):

העושה מלאכות הרבה מעין מלאכה אחת אינו חייב אלא חטאת אחת.

He who performs many acts of labor that are like one labor is liable only for a single sin offering.

As we saw earlier, according to the strict original form of the mishnah’s third case, a person is liable for a sin offering for each labor. Here, in the fourth case, the mishnah modifies this strict view with a leniency, obligating a person for only one sin offering if the acts of labor are all “like one labor.”

But what does the phrase “many labors that are like one labor” mean?[11] The Tosefta (Shabbat 9:17–20), a collection of tannaitic materials from the same time period as the Mishnah, demonstrates that this term can refer to two different affinity groups:

1. Paradigmatic (Parallel) Set—The first type is a paradigmatic set, i.e., a set of parallel activities all of which achieve a similar outcome but for different products (t. Shabbat 9:17):

החופר והחורש והחורץ מלאכה אחת.

One who digs, plows, and cuts a trench, [these are] one labor.

הדש והכותש והנופט מלאכה אחת.

One who threshes, beats flax, and gins cotton, [these are] one labor.

התולש והקוצר והבוצר והמוסק והגודר (והעודר) [והאורה] מלאכה אחת הן.

One who pulls up, reaps, cuts [grapes], harvests [olives], cuts dates, and cuts figs, these are one labor.

This type of affinity is unanimously considered a violation of only one labor in the Tosefta.

2) Syntagmatic (Sequential) Set—The second type of affinity is a syntagmatic set, i.e., a series of sequential steps which all lead to one outcome, like the sequence of activities one engages in to bake a loaf of bread. And indeed, the Tosefta describes a dispute between the sages about whether this should be considered one form of labor or many forms of labor (t. Shabbat 9:18):

המכבס והסוחט מלאכה אחת. ר' ישמעאל בי ר' יוחנן בן ברוקה או' צבעים קבעו סחיטה מלאכה בפני עצמה...

One who launders and one who wrings out, [these are] one labor. R. Ishmael son of R. Yohanan b. Baroka says: “[Professional] dyers have determined that wringing out is a labor unto itself.”

A later passage in the same chapter lists another series and presents it unanimously as multiple acts of labor (t. Shabbat 9:20):

התולש כנף מן העוף הקוטמו והמורטו חייב שלש חטאות.

One who pulls a wing from a bird, trims it, and plucks the down, is liable for three sin-offerings.

In short, the Tosefta suggests that there are two ways of coordinating multiple activities into “one labor”: either as a paradigmatic set in which the activities are similar to each other in outcome (9:17), or as a syntagmatic series in which the activities are each regarded as separate steps in a larger process (9:18 [R. Ishmael], 20).

Clarifying: Not Applicable to Syntagmatic Groups

With this context in mind, I suggest that Mishnah Shabbat 7:2 does not come to present 39 primary categories of forbidden Shabbat labors,[12] but to modify the final line of Mishnah 7:1, by clarifying that this leniency applies only to paradigmatic groups, not to syntagmatic groups. The list of syntagmatic groups of labor in 7:2 shows that each should be viewed as a separate act requiring its own sin offering. In adding this clarification, the editor took a line that was entirely lenient, and modified it in the direction of stringency.[13]

The redactor who added this list was not trying to be comprehensive or clarify the exact meaning of each labor; instead he focused on including large lists of syntagmatically related labors. Thus, he opens with three lengthy syntagmatic series—eleven activities leading to the production of a loaf of bread, thirteen activities leading to the production of a piece of cloth, and seven activities leading to the production of a piece of leather—in order to argue that each activity results in a separate liability.[14]

Syntagmatic Series in Non-Shabbat Contexts

The creator of this list did not invent these syntagmatic series on his own, but took them from other contexts, not necessarily relevant to Shabbat laws. Two of these syntagmatic series appear in Tosefta Berakhot 6:2 in a non-legal context:

בן זומא כשראה אוכלסין בהר הבית או' ברוך מי שברא את אלו לשמשני כמה יגע אדם הראשון ולא טעם לוגמה אחת עד שזר' וחרש וקצר ועמר ודש וזרה וברר וטחן והרקיד ולש ואפה ואחר כך אכל ואני עומד בשחרית ומוצא אני את כל אילו לפני

When Ben Zoma saw a crowd on the Temple Mount, he said: “Praised be He who created [all] these [people] to serve me. How hard did Adam toil before he could taste a morsel [of food]: he seeded, he plowed, reaped, sheaved, threshed, winnowed, separated, ground, sifted, kneaded, and baked, and only then could he eat. But I arise in the morning and find all these [foods ready] before me.

כמה יגע אדם הראשון ולא לבש חלוק עד שגזז ולבן ונפס וצבע וטווה וארג ואחר כך לבש ואני עומד בשחרית ומוצא את כל אילו לפני...

How hard did Adam toil before he could put on a garment: he sheared, bleached, separated, dyed, spun, and wove, and only then could he put it on. But I arise in the morning and find all these [garments] ready before me…”[15]

The redactor of the Mishnah likely knew these “readymade” series of activities and constructed his mishnah around them, not in order to offer a complete list of forbidden labors, but to teach that one who performs a series of sequential activities on Shabbat is liable for a separate punishment for each action he performed. It is only in the Talmud and post-Talmudic literature that the concept of 39 primary labors develops into what is now the core systematization of Shabbat laws ubiquitous in halakhic literature.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

February 13, 2020

|

Last Updated

February 8, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Rabbi Judith Hauptman is the E. Billi Ivry Professor of Talmud and Rabbinic Culture at JTS and a fellow of the American Academy of Jewish Research. She holds a Ph.D. in Talmud from JTS and rabbinic ordination from the Academy for Jewish Religion. Among her books are Rereading the Rabbis: A Woman’s Voice, Development of the Talmudic Sugya: Relationship between Tannaitic and Amoraic Sources, andRereading the Mishnah: A New Approach to Ancient Jewish Texts.

Essays on Related Topics: