Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Heterodox Responses

Writing a Torah scroll – Wikimedia. According to the Pew Report 53% of Jews believe the Torah was written by men, and is not the word of God

(1881 – 1983)

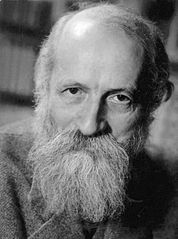

Before discussing possible “Orthodox” solutions, it would be useful to first survey some “heterodox” (i.e. non-Orthodox) suggestions that have been proffered. One heterodox response to these difficulties—perhaps the most intuitively obvious one—has been to abandon the notion of divine revelation altogether. Thus, Mordecai Kaplan, founder of the Reconstructionist movement, rejects any appeal to metaphysics and transcendence in describing the origins of the Torah. Instead, he prefers to view revelation naturalistically, as the human “discovery” of how to live religiously.

To say that religion is a creation of human beings does not imply that it is a figment of the imagination – religion flows naturally and intuitively from an innate religious impulse. But saying this does relegate an exclusive role to humans in shaping the content of revelation. That content merely expresses the function of God as a process or power within the natural order, without reference to any process or power beyond.[1]

Other responses that have been rejected by mainstream Orthodoxy, such as those represented in the writings of Franz Rosenzweig, Abraham Joshua Heschel, and Louis Jacobs, all appear to be variations on Martin Buber’s attempt to promote a more nuanced understanding of revelation that does not reject biblical claims to metaphysics altogether.[2]

(1878 – 1965)

Buber’s complex approach to the biblical text understands everything in the Torah that is said about God as a human effort to convey or recapture certain genuine meetings with the divine. Nevertheless, because such meetings were inevitably experienced in a particular linguistic and cultural context that structured the nature of the experience and its interpretation, the question becomes just what and how much of the Godly was revealed in that meeting. This problem is exacerbated when one takes into account the fact that no written or oral report can totally successfully convey these encounters in terms that are entirely free of the influence of historical context.

Differences of opinion regarding how much of our recorded revelation accurately reflects the message of the divine encounter range over a great distance. Some have suggested the minimal notion that the divine element consisted merely in the meeting itself with all resultant texts a human response. Others, taking a more expansive approach, suggest that a complete text was given but that it was (necessarily) distorted, since every human “hearing” involves re-interpretation. A compromise position, situated between these two poles, suggests that a more minimalistic linguistic message was relayed and left for humans to fill in, interpret and expand over time.[3] According to this, what remains for us is to extract the eternal illuminations that the Torah communicates to us from those trappings that are the fruit of passing human experience.

Viewing revelation as a dialogic encounter which entails both human and divine elements appears more satisfactory than Kaplan’s reductionism. Instead of understanding the religious experience as merely the product of innately human impulses, this approach acknowledges biblical claims to a supernatural source. However, a theology that relates to the Torah as the product of divine inspiration rather than as a full-fledged word-for-word dictation may not provide sufficient basis for fulfilling the traditional requirement that the entire Torah be viewed as the word of God and that all its details be regarded as equally authoritative and binding.[4]

And so the question remains: Can a document so thoroughly riddled with identifiably dated and partisan human perspectives truly be divine? Can traditionalists develop an approach to the Torah that acknowledges the naturalist explanations of Mordecai Kaplan without his reductionism on the one hand, and simultaneously appropriate the metaphysical claims of dialectical theology without succumbing to selectivity, on the other?

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 25, 2014

|

Last Updated

January 12, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Tamar Ross is Professor Emeritus of the Department of Jewish philosophy at Bar Ilan University. She continues to teach at Midreshet Lindenbaum. She did her Ph.D. at the Hebrew University and served as a post-doctoral fellow at the Center for Jewish Studies at Harvard. She is the author of Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism. Her areas of expertise include: concepts of God, revelation, religious epistemology, philosophy of halacha, the Musar movement, and the thought of Rabbi A.I. Kook.

Essays on Related Topics: