Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Is the "As If" Approach Sufficient to Maintain Firm Religious Commitment?

“Slichot” prayer service during the Days of Repentance preceding Yom Kippur at the Western Wall in Jerusalem's Old City. GPO photo by Mark Neyman.

Post-liberals do not have a monopoly on an “as if” approach to religious doctrine. Indeed, it would be fair to say that most believers in the past assumed such an attitude unreflectively, simply allowing the concrete experience of their everyday lives to be shaped by the truth claims of their religious tradition, without dwelling overmuch on their precise doctrinal content.

More specifically, professions of belief in divine revelation for rank and file traditional Jews, then as now, signified loyalty to the Torah and the way of life that it propagates. Nevertheless, it must be admitted that when the “as if” quality of religious belief is adopted consciously and deliberately as a blanket response to newfound awareness that the doctrine of Torah from Heaven may not be literally “real” or “true” in any common-sense understanding of these terms, conducting one’s day to day living in accordance with its guidelines could be more problematic.

Applying an “as if” approach in order to speak descriptively and after-the-fact regarding the function of particular aspects of our religious language is one thing; appropriating this approach in advance, as a general panacea is quite another. Conscious and wholesale reliance upon “as if” understandings invites openness to the possibility of various levels of commitment to the belief structure as a whole because the grip of its picture upon us is no longer complete. While the narrative framework typically functions as a type of (Kantian) a-priori-like scheme for the simple believer, the moment one acknowledges the possibility that any religious statement parading as truth is capable of being understood simply as a construct, all that such an a-priori scheme amounts to is a system of acquired skills that could have been otherwise.[1]

This difficulty has been portrayed inimitably on the internet, by a Modern Orthodox blogger tormented by his crisis of faith in the notion of a divinely revealed Torah. In his search for a solution over several years, he covered many of the positions described above, aided and abetted by the considerable virtual community he drew around him. When finally arriving at appreciation of the “as if” position, however, he vividly portrays the dilemma that such self-awareness raises:

Someone once commented on one of my many former blogs that religion is a form of kabuki (Japanese theatre). And this time of year, the theater is in full swing.

Right now it’s Tisha B’av. We feel sad and mournful. We act sad, we do sad rituals like eating egg in ash and sitting on the floor. The mood is oppressive and depressing. We breathlessly focus on every car crash and other bad events that always seem to happen davka during the three weeks. We say platitudes about the importance of achdus. We even hold asefas and have top lawyers give us mussar. We complain about the lack of fleishigs. We can’t wait for it to end.

But deep down, we kinda enjoy it I think. I could have just skipped Tisha B’av this year completely. I mean, why bother? What’s the point? But as soon as I heard the first words of Eichah, I was glad I didn’t skip it. It’s a powerful piece of theater. Just like we enjoy going to sad or scary movies, we enjoy Tisha B’av. It feels good to feel bad. Then of course we have Shabbos Nachamu, and then Ellul. Ever spent Ellul in a REAL Yeshiva? I have. And I can still remember how powerful it was, and probably always will.

Rosh Hashana, Yom Kippur Succos – all elaborate theater. Complete with costumes, props, drama, comedy, scary parts, happy parts – it’s all there. Where do you get such thrills, such feelings in everyday life? From the movies? From going to the bar every night? Maybe you can, or maybe life feels somehow emptier and more vacuous.

And it’s not just the Yomim Noroim where the performances are stellar. Every Shabbos, every Friday night, every Seuda Shelishis, in a decent shul (and not some kalte MO intellectual place) is elaborate theater. And even every day has a little bit of theater – shacharis, mincha, maariv. Even a humble bracha – you’re talking to THE SUPREME BEING for goodness sake! And not only that, HE’S FREAKING LISTENING TO YOU! The drama is overwhelming.

True, sometimes you need a break. Too much of a good thing and all that. Plus, if you keep reminding yourself that it’s only a show, it can get annoying, especially when too much audience participation is required. But who goes to a great movie and sits there during the scary bits saying out loud: “They’re just actors, the cameraman is right there!”?… We enjoy the performance; we want it to be as real as possible. It’s Tony and Tina’s Wedding show writ large.[2] And maybe there’s something to that. If only I could just forget about that damn camera-man.[3]

Surely, the fact that myths of origin in all religions present themselves as historical accounts, imposing an aura of objectivity, has something to do with their staying power. It also has something to teach us regarding a universal human need to ground our religious commitments on firmer territory than the product of a cameraman, no matter how powerful the show.

Conveying reasonable import may not be the main function of religious truth claims, but a strong sense that their ultimate referent is unreasonable (that is to say, ungrounded in reality) might well render them ineffective in accomplishing the regulative function for which they are meant: i.e., to compose the “picture” that stands behind the religious form of life. Hence, when doctrines that are part and parcel of the religious form of life appear untenable, the post-liberal constructivist no less than any other conflicted believer will feel impelled to subject them to an additional line of defense that will remove such complaints.[4]

So long as this additional defense is conducted from within the religious discourse itself (i.e., attempting to substantiate the path of a particular religion on its own terms), the self-aware post-liberal can still travel hand in hand with the naïve rank and file believer for a very long way in preserving the psychological force of his or her religious commitments. For all practical purposes, the two will not differ radically on this level in the mix of pragmatism and realist rhetoric that they may adopt in order to defend the claims upon which such commitments rest.

In the case of descriptive statements open to critical scientific investigation (such as the age of the universe, the splitting of the Red Sea, the chronology of biblical accounts), the sophisticated believer adopting a cultural-linguist approach will find the task of relating such statements to a presumed reality relatively easy. There already exists a long history of naturalistic or allegorical interpretations within the religious tradition itself upon which such a believer can draw. Although his or her attachment to the tradition will not rise or fall on the results of this enterprise, he or she may well regard such efforts at reconciling reason with faith as part and parcel of the religious language game itself.

Dealing with mythic explanations of descriptive statements that border on the historic is also relatively unproblematic. We may have no way of knowing whether or not the Red Sea did indeed split, whether the ancient Hebrews really did undergo some revelatory experience at Sinai, whether someday there actually will appear a Messiah who will inaugurate a new epoch in the history of mankind.

Nonetheless, even when such explanations assume the existence of metaphysical forces or an occurrence of historic events not liable to scrutiny, the sophisticated believer adopting a cultural-linguistic approach will find no problem in employing traditional religious vocabulary grounded on “realist” epistemological assumptions. Such a believer can justify this practice in terms of the spiritual attitudes, which they engender, and the ways of reacting to and meeting situations which they inspire.

In the event that the difficulty posed to religious belief stems from statements that are even farther removed from rational demonstration or confirmable human experience, more innovative theological solutions can also be brought into the fray. God’s justice, despite the Holocaust, may be explained as reflecting a new development in the covenantal relationship with the nation of Israel, in which divine responsibility is abdicated in the interests of greater equality between the partners. By the same token, mythic talk of God’s dictation and dogmatic assertions that every word of the Torah was transmitted from Heaven by direct dictation may be refined by focusing on those strands in Jewish tradition that can be understood as supporting current theological consensus regarding God’s pure spirituality or our common sense notions of reality.

Even if all religious believers accept the premise that when speaking of matters of faith we must at some stage turn to non-representational modes of expression that do not purport to simply state “the facts of the matter,” nevertheless, much of the emotional fervor characterizing debates regarding deviations from literalism will remain. This further stems from the question: “to what extent can the move from a propositional to an “as if” mode be tolerated or condoned?” Does it stop at the point of non-literal interpretations of God’s mighty arm, God’s creation of the world in six days and resting on the seventh, God’s fashioning of Adam from the dust of the earth and Eve from his side (or rib), or the hearing of God’s voice at Sinai?

We often tend to ignore the fact that what is really at stake in such debates is not the question: “what degree of objective difficulty posed by historical or philosophical insights to the religious framework compels fine-tuning?” What really concerns us is the question: “where exactly does the key to our ultimate commitment lie?”

If we accept the premise that even the most basic claim of divine revelation can only be justified from within the specific vocabulary of a particular religious tradition, do we have any recourse to a transcendent vantage point that extends beyond the human desires, values and visions that this tradition expresses? In other words, can we speak from within an “as if” context of a reality that is free of context? If not, what justification might there be for reference to overarching metaphysical claims that can only be judged from within?

Philosopher Jeffrey Stout’s wry characterization of the position he identifies as “skeptical realism” (i.e., questioning whether words refer to any pre-defined objective reality) aptly illustrates the dilemma of a die-hard constructivist at this stage of religious belief:

The skeptical realist is more like someone who wants to be his own father and then has the nature of that desire brought to light in therapy. He might be unhappy, perhaps even hard to console, upon realizing that he will never be his own father, but it’s hard to see how he could have good reason for wallowing in the disappointment of such an incoherent desire. What fuels the unhappiness, it seems safe to suppose, is still half-thinking that maybe the desire does make sense.[5]

At this point, it would appear that even a constructivist approach to balancing the tension between cognitive dissonance and religious loyalty (i.e., an approach that regards religious beliefs as useful tools rather than inevitable representations of a reality independent of the human mind) reaches the limits of its apologetic power. “As if” explanations may serve to over-ride localized intellectual and moral difficulties raised by religious claims that appear on the surface as propositions, but can such a view – when sidestepping the dubious ontological status of religious symbols altogether – leave us with anything more than a feeble motive for abiding religious commitment?

The inherent inability of post-liberalism to provide a patent “objectivity” that is at any point guaranteed by reference to some factor that exceeds the limits and partisan biases of human experience inevitably leads all who struggle with this question from the psychological difficulty to the philosophical one. Given the premise that true religious commitment must be tied to some sense of divine transcendence, can we know or experience a God that is by definition beyond definition and beyond our grasp?

In recent years, a new stream of pragmatist philosophers (including Stout himself)[6] have been struggling to rehabilitate some version of truth and objectivity whose authority extends beyond social consensus, communal solidarity, and pragmatics even in secular terms. In the concluding paragraphs of his book, Solomon may be intimating the need to address this issue in the religious context, when he admits that classifying the doctrine of Torah from Heaven as myth is “only one part of a bigger story.”[7]

Changing the status of the doctrine of Torah from Heaven from historical truth to foundational myth may by-pass many specific questions arising out of the clash between scientific and religious world-views, thereby counteracting the dialectical theologians’ basis for selectivity. But due to its anomalous juxtaposition of insider and outsider perspectives (man “hears” God’s voice, yet the very talk of God and His communication with man is “as if”, and ontologically dubious), and the centrality of this essentially paradoxical stance to the religious way of life, its metaphysical claims are sui generis, a special case.

Simply assuming the conceptual coherence of a God that verbally communicates with man, while ignoring the dubious ontological status of such talk, is insufficient when conducted within an “as if” framework that is self-aware. In order to accomplish its psychological task, a constructivist assumption of divine communication must also engage in serious examination of what “And the Lord spoke to Moses” might possibly mean even beyond its own self-certifying justification as the linchpin for a spiritually meaningful way of life.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

March 25, 2014

|

Last Updated

January 26, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

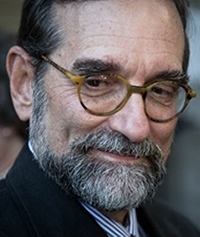

Prof. Tamar Ross is Professor Emeritus of the Department of Jewish philosophy at Bar Ilan University. She continues to teach at Midreshet Lindenbaum. She did her Ph.D. at the Hebrew University and served as a post-doctoral fellow at the Center for Jewish Studies at Harvard. She is the author of Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism. Her areas of expertise include: concepts of God, revelation, religious epistemology, philosophy of halacha, the Musar movement, and the thought of Rabbi A.I. Kook.

Essays on Related Topics: