Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Isaac Dies in the Akedah: From Bible to Midrash to Art

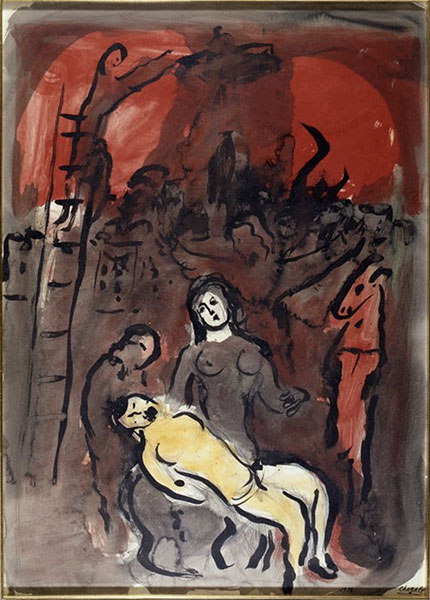

Abel Pann, The Binding of Isaac, 1940’s. Private collection.

Art depicting Isaac lying bound on the altar,[1] about to be saved by the angel, can be traced back at least to the third-century C.E. wall paintings of the Dura-Europos synagogue (Syria)[2] and continues into more recent times, for example, in the work of the Ukrainian-Jewish artist Emmanuel Mané-Katz including his Sacrifice of Isaac (1943).[3]

Yet in the 20th century, some Jewish artists depicted Isaac in a new and shocking way: as dead. The story of how this happened can be traced back to the biblical text itself.

Isaac Is Bound on the Altar

In the biblical narrative Isaac is bound on the altar:

בראשית כב:ט וַיָּבֹאוּ אֶל הַמָּקוֹם אֲשֶׁר אָמַר לוֹ הָאֱלֹהִים וַיִּבֶן שָׁם אַבְרָהָם אֶת הַמִּזְבֵּחַ וַיַּעֲרֹךְ אֶת הָעֵצִים וַיַּעֲקֹד אֶת יִצְחָק בְּנוֹ וַיָּשֶׂם אֹתוֹ עַל הַמִּזְבֵּחַ מִמַּעַל לָעֵצִים.

Gen 22:9 They arrived at the place of which God had told him. Abraham built an altar there; he laid out the wood; he bound his son Isaac; he laid him on the altar, on top of the wood.[4]

But it seems clear that he is not killed; he is rescued by an angel who commands Abraham to stop the sacrifice:

בראשית כב:י וַיִּשְׁלַח אַבְרָהָם אֶת יָדוֹ וַיִּקַּח אֶת הַמַּאֲכֶלֶת לִשְׁחֹט אֶת בְּנוֹ. כב:יא וַיִּקְרָא אֵלָיו מַלְאַךְ יְ־הֹוָה מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם וַיֹּאמֶר אַבְרָהָם אַבְרָהָם וַיֹּאמֶר הִנֵּנִי. כב:יב וַיֹּאמֶר אַל תִּשְׁלַח יָדְךָ אֶל הַנַּעַר וְאַל תַּעַשׂ לוֹ מְאוּמָה כִּי עַתָּה יָדַעְתִּי כִּי יְרֵא אֱלֹהִים אַתָּה וְלֹא חָשַׂכְתָּ אֶת בִּנְךָ אֶת יְחִידְךָ מִמֶּנִּי.

Gen 22:10 And Abraham picked up the knife to slay his son. 22:11 Then an angel of YHWH called to him from heaven: “Abraham! Abraham!” And he answered, “Here I am.” 22:12 “Do not raise your hand against the boy, or do anything to him. For now I know that you fear God, since you have not withheld your son, your favored one, from Me.”

Instead, a ram is provided for the sacrifice:

בראשית כב:יג וַיִּשָּׂא אַבְרָהָם אֶת עֵינָיו וַיַּרְא וְהִנֵּה אַיִל אַחַר נֶאֱחַז בַּסְּבַךְ בְּקַרְנָיו וַיֵּלֶךְ אַבְרָהָם וַיִּקַּח אֶת הָאַיִל וַיַּעֲלֵהוּ לְעֹלָה תַּחַת בְּנוֹ.

Gen 22:13 When Abraham looked up, his eye fell upon a ram, caught in the thicket by its horns. So Abraham went and took the ram and offered it up as a burnt offering in place of his son.

But Then Why Does Abraham Return Alone?

Yet Isaac is absent when Abraham returns to his servants.

בראשית כב:יט וַיָּשׇׁב אַבְרָהָם אֶל נְעָרָיו וַיָּקֻמוּ וַיֵּלְכוּ יַחְדָּו אֶל בְּאֵר שָׁבַע וַיֵּשֶׁב אַבְרָהָם בִּבְאֵר שָׁבַע.

Gen 22:19 Abraham then returned to his servants, and they departed together for Beer-sheba; and Abraham stayed in Beer-sheba.

The midrash Genesis Rabbah (mid-1st millennium C.E.) notes Isaac’s absence, and imagines that Abraham sent him to study Torah:

בראשית רבה נו:יא וַיָּשָׁב אַבְרָהָם אֶל נְעָרָיו, וְיִצְחָק הֵיכָן הוּא, רַבִּי בֶּרֶכְיָה בְּשֵׁם רַבָּנָן דְּתַמָּן, שְׁלָחוֹ אֵצֶל שֵׁם לִלְמֹד מִמֶּנּוּ תּוֹרָה.

Bereshit Rabbah 56:11 “Abraham returned to his young men” – and where was Isaac? Rabbi Berekhya in the name of the Rabbis from over there (Babylon): He sent him away to Shem to learn Torah from him.[5]

A more straightforward explanation is suggested, for example, by the Radak (Rabbi David Kimhi, 1160-1235 C.E.):

רדק על בראשית כב:יט:א ואין צריך לומר כי יצחק היה עמו, אלא זכר אברהם שהוא העקר.

Radak on Gen 22:19a There was no need to mention that Isaac accompanied him. Rather it mentioned Abraham, because he was the principal.[6]

Still, this troublesome verse gave rise to the exegetical possibility that Isaac was actually in some sense slaughtered.

Isaac Was Sacrificed: Projecting Grief in the Present into the Past

The introduction to the midrash Eichah Rabbah (5th century C.E.) has Abraham challenging God for destroying the temple, the place where he brought Isaac as an “olah” (burnt offering) sacrifice:

איכה רבה, פתיחתא כד רִבּוֹנוֹ שֶׁל עוֹלָם מִפְּנֵי מָה הִגְלֵיתָ אֶת בָּנַי וּמְסַרְתָּן בִּידֵי הָאֻמּוֹת וַהֲרָגוּם בְּכָל מִיתוֹת מְשֻׁנּוֹת, וְהֶחֱרַבְתָּ אֶת בֵּית הַמִּקְדָּשׁ מָקוֹם שֶׁהֶעֱלֵיתִי אֶת יִצְחָק בְּנִי עוֹלָה לְפָנֶיךָ.

Lamentations Rabbah Petichta 24 Master of the world, why have you exiled my children and given them over into the hands of the nations who have killed them with all manner of strange deaths? And you destroyed the Temple, the place where I offered my son as a burnt offering before you.[7]

Similarly, the kinnah (lament) Az Behalokh Yirmiyah, “Then as Jeremiah Walked,” recited on Tisha B’Av and written by Byzantine liturgist Elazar Hakalir in the 6th-7th century C.E., describes the different patriarchs and matriarchs pleading for mercy on behalf of their descendants. In the lament, Isaac asks,

קינות ליום תשעה באב כו לַשָּׁוְא בִּי טֶּבַח הוּחַק וְהֵן זַרְעִי נִשְּׁחַק וְנִמְחַק

Kinnot for Tish B’av Day, 26 Have I been butchered in vain, that my children are being killed?”[8]

The chronicle of Solomon bar Samson (ca. 1140 C.E.) describes the massacre of Jewish communities during the First Crusade in terms of the Akedah:

גזרות ד'תתנו לרבי שלמה ב"ר שמשון האם היו אלף ומאה עקידות ביום אחד כולם כעקידת יצחק בן אברהם. על אחד הרעיש העולם, אשר נעקדה בהר המוריה, שנאמר . . . ו [רעשו] שמים [שמש וירח] קדרו [וכוכבים אספו נגהם]. מה עשו, למה השמים לא קדרו והכוכבים לא אספו נגהם...

Chronicle of R. Solomon bar Samson Were there ever 1,100 Akedot on one day—all of them like the Akedah of Isaac, son of Abraham? The earth rumbled over just one Akedah that was bound on Mount Moriah, as it is said, “And the heavens [trembled, the sun and moon] grew dark, [and the stars gathered in their brightness]” (Joel 2:10). What did they do now? Why did the heavens not grow dark and the stars not hold back their splendor?[9]

These texts of grief and lamentation project the horror of the present moment into the past, where Isaac died like his descendants. Paradoxically, however, they are also texts of hope, because Isaac did not in fact die but rather lived to have descendants.

Isaac Died and Was Resurrected

While these texts poetically evoke Isaac as being sacrificed, but not necessarily dying, Pirkei de Rabbi Eliezer (8th century C.E.) explicitly records Isaac’s death:

פרקי דרבי אליעזר לא:י רַבִּי יְהוּדָה אוֹמֵר: כֵּיוָן שֶׁהִגִּיעַ הַחֶרֶב עַל צַוָּארוֹ, פָּרְחָה וְיָצְאָה נַפְשׁוֹ שֶׁל יִצְחָק. וְכֵיוָן שֶׁהִשְׁמִיעַ קוֹלוֹ מִבֵּין הַכְּרוּבִים וְאָמַר לוֹ ״אַל תִּשְׁלַח יָדְךָ״, נַפְשׁוֹ חָזְרָה לְגוּפוֹ, וְקָם וְעָמַד יִצְחָק עַל רַגְלָיו. וְיָדַע יִצְחָק שֶׁכָּךְ הַמֵּתִים עֲתִידִים לְהֵחָיוֹת, וּפָתַח וְאָמַר: ״בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה' מְחַיֵּה הַמֵּתִים״.

Pirkei de R. Eliezer 31:10 Rabbi Jehudah said: When the blade touched his neck, the soul of Isaac fled and departed, (but) when he heard His voice from between the two Cherubim, saying (to Abraham), “Do not lay your hand upon the lad” (Gen. 22:12), his soul returned to his body, and (Abraham) set him free, and Isaac stood upon his feet. And Isaac knew that in this manner the dead in the future will be restored to life. He opened (his mouth), and said: Blessed are you, O Lord, who restores the dead to life.[10]

This midrash here imagines that the second blessing of the Amidah, reviving the dead, was proclaimed by Isaac.[11] The Shibbolei Ha-Leket (a work by Zedekiah ben Abraham Anav, Italy, 13th-Century) has God resurrecting Isaac with dew:

שבלי הלקט יח כשנעקד יצחק אבינו על גבי המזבח ונעשה דשן והי' אפרו מושלך על הר המוריה מיד הביא עליו הקב"ה טל והחיה אותו לפיכך אמר דוד כטל חרמון שיורד על הררי ציון וגו' כטל שהחיה בו יצחק אבינו מיד פתחו מלאכי השרת ואמרו בא"י מחיה המתים.

Shibbolei Ha-Leket 18 When our father Isaac was bound on the altar and reduced to ashes, and his ashes were cast on to Mount Moriah, the Holy One, blessed be He, immediately brought dew upon him and revived him. Therefore David said, “Like the dew of Hermon that falls on the mountains of Zion, etc.” (Ps 133:3) Like the dew that revived Isaac our father. Immediately the ministering angels began to recite “Blessed are you, God, who revives the dead.”[12]

The Midrash HaGadol, a midrashic collection from 13th/14th century Yemen, has Isaac living in the Garden of Eden three years:

מדרש הגדול בר׳ כב:יט ד״א וישב אברהם. ויצחק היכן הוא? אלא שהכניסו הקב״ה לגן עדן וישב שם בה שלוש שנים.

Midrash HaGadol Gen. 22:19 Another interpretation: And Abraham returned... And where was Isaac? The Holy One brought him into the Garden of Eden and he dwelt there three years.[13]

Isaac Actually Died

Perhaps the clearest evidence that some interpreters believed that Isaac actually died and Abraham went back alone can be found in Ibn Ezra’s (1089–1167) dismissal of this reading:

אבן עזרא על בראשית כב:יט וישב אברהם. ולא הזכיר יצחק, כי הוא ברשותו והאומר ששחטו ועזבו, ואח"כ חיה אמר הפך הכתוב.

Ibn Ezra on Gen 22:19 So Abraham returned. Isaac is not mentioned because he was under Abraham’s care. Those who say that Abraham slaughtered Isaac and left him on the altar and following this Isaac came to life are contradicting Scripture.[14]

Indeed, some modern scholars argue that there was an early version of the story in which Isaac actually dies and Abraham leaves him, which was later redacted so that Isaac is spared.[15] Thus it is not surprising that later generations intuited this earlier version of the story with Isaac actually dying.

Isaac’s Death in Contemporary Art: Abel Pann

In the early 20th century, artists also depict Isaac’s death as a way of expressing grief and anger about the pogroms, the Holocaust, and the loss of loved ones to war. Some of these depictions can also express some hope that out of this loss comes the possibility of renewal. The first twentieth-century artist to depict Isaac as dead was the Latvian-born[16] Israeli painter Abel Pann (1883–1963), who was one of the influential teachers in the early years of the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem. Abel Pann addressed the Akedah several times in his œuvre.[17]

One of his earliest and most famous renderings of this theme is a 1923 color lithograph depicting Abraham holding Isaac in one arm and the knife in the other. Isaac is immobile and shows no signs of life.

In his later rendering, from the 1940s, Abraham is pressed against Isaac’s lifeless face.[18] In both, God and the angel are entirely absent; all that matters is Abraham’s grief over Isaac. (See main image above.)

Both images depict a devastated Abraham and both come from Pann’s own experience of grief, as someone who documented pogroms in his art, in particular the Kishniev pogrom in 1903 and those in World War 1.[19] At the time Pann painted the second image his own son Eldad was in danger as a fighter in the Palmach, and Eldad was killed in the battle for Gush Etzion in May 1948.[20] Pann was, like the Abraham he painted, a father mourning his dead son.

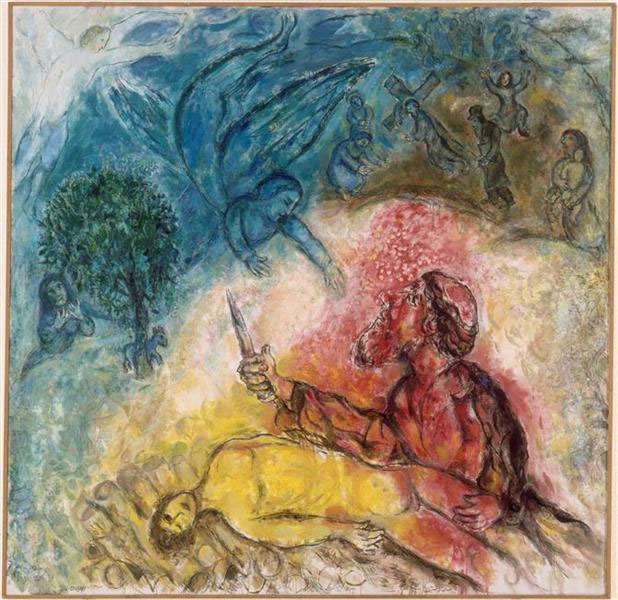

Marc Chagall

Marc Chagall (1887-1985), Belarusian-born, French citizen, and one of the most celebrated artists of the 20th century, also uses the Akedah to express grief over the devastation of Jewish communities in Eastern Europe, in particular during the Holocaust. He depicted the Akedah several times. His 1931 painting The Sacrifice of Isaac, which he painted before Hitler’s rise to power, portrays a traditionally optimistic version of the story in which an angel prevents Abraham from killing his son.

In two others, composed after the Holocaust, it seems that Isaac is dead.

In the Pietà Rouge (1956), from after the world knew about the destruction of the Shoah, Chagall draws on the Christian artistic motif of the Pietà in which Mary cradles the body of her dead son Jesus. Isaac lies in the lap of a woman, while the ram that was supposed to replace him watches. This all takes place against a red apocalyptic landscape.

In The Sacrifice of Isaac (1960-66), Chagall focuses on Abraham and Isaac, with other figures at a distance. Isaac’s body is lying, immobile, on wood beams with his right arm calmly placed across his torso. Isaac is yellow, symbolizing the yellow star of the Holocaust, and red, evoking death and destruction. In the background a woman prays or perhaps grieves.[21]

Chagall here builds on the medieval Jewish tradition where the dead Isaac is a way of depicting grief. Isaac is dead because his descendants are dead. Depicting Isaac as alive might be true to the biblical story but false to the reality in which the artist lived, in which so few survived.

Despite all the destruction, Chagall’s painting includes images that suggest God’s presence at the scene. It depicts an angel, even if it may have come too late, and the divine presence is depicted behind the angel, even if it does not intervene to stop the death of Isaac. Abraham looks up, towards the angel and towards heaven. Isaac’s death has not completely severed the relationship between God and humanity.

Samuel Bak

In the work of Lithuanian-Israeli artist Samuel Bak (1933-), who survived the destruction of the Vilna ghetto as a child, the idea of reaching towards God is entirely absurd after God’s absence in the Holocaust. Bak writes in his memoir of a deal that he proposed to his mother before cancelling his Bar Mitzvah: “if God would come to me and apologize for the deaths of my father, my grandparents, and millions of my people, I would celebrate a Bar Mitzvah”[22]

The word Holocaust is in its origins a translation of the biblical Hebrew olah, a completely burnt offering. This language carries with it theological baggage, imagining the Jews murdered by Nazis as sacrificial victims, and many Jewish scholars find it inappropriate.[23] Bak also found the term disturbing, but expressed it by literalizing the metaphor.[24]

He refers to the dead Isaac in his two works: Burning and Icon of Loss. For Bak, Isaac is a specific Holocaust icon and a famous Holocaust victim: the Warsaw Ghetto boy immortalized by a photo taken by the Nazis officers during the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto between April 19 and May 16, 1943.[25] In Burning the boy wears a brown coat and short trousers with brown socks and boots, and stands on a mountain carrying on his body several tree branches, the upper part of which is on fire.

Isaac holding the tree branches is a reference to Isaac carrying the wood for his own sacrifice (Gen 22:6), but rather than carrying the wood he is trapped by it. In Icon of Loss, the same boy now wears blue socks, and stands not directly atop a mountain but on an altar made provisionally from a pile of stones and flagstones placed on a mountain-top. To his right is a rope and knife, key visual elements of the Genesis story (v. 9), and he is standing on an altar. This boy appears terrified, as the fire engulfing the tree branches attached to his body is burning intensely and will soon begin to consume his body.

For Bak, the Warsaw Ghetto boy represents the murdered Holocaust victims, and his murdered friends, in particular.[26] In his representations of the Akedah, no angel is there to stop the murder of Isaac, or the Warsaw Ghetto boy, and no God is there to give it meaning. In the absurd, godless universe, Isaac is doomed.

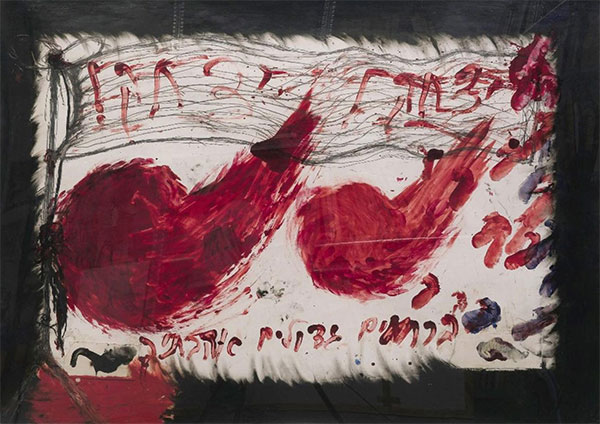

Moshe Gershuni

The work of Israeli artist Moshe Gershuni (1936-2017)[27] shows grief over the death of Isaac but also a strong sense of anger. Working against the backdrop of Israel’s war in Lebanon, Isaac is a dead soldier, a victim of the war. During the Lebanon war Gershuni returned to the death of Isaac many times, in Yitzhak (1982), Yitzhak, Yitzhak with Great Pity I Have Loved You (1982), and My Little Isaac (1983).

His work Yitzhak, Yitzhak (1984) writes the blood-smudged blood-red name of Isaac twice on a bloody, torn flag. Surrounding the flag are other words, some barely legible, drawing on Jewish tradition, including the phrase “God, the soul you gave me is pure” from the morning blessings and “the fallen sukkah of David” (from Amos 9:11). These barely legible verses of hope and consolation surround the blood-red cry of Isaac’s name.

For Gershuni, the violence around Isaac was personal as well as political. In 1980 Gershuni experienced a breakdown. He declared his homosexuality and love for a young soldier whose name was Isaac and left his wife and family. Gershuni’s paintings express his grief at the homophobia he and Isaac experienced as well as anger about the dangers Isaac faced in war.

Isaac as the name on the blood-stained flag represents an inversion of any hope there was in the original story of the Akedah. Not only does Isaac die, he dies not for God but for a parody of nationalism. God is not only absent but replaced by something murderous.

Menashe Kadishman

The work of another Israeli artist, Menashe Kadishman (1932-2015), similarly uses the dead Isaac as a rebuke, but from a very different perspective.[28] In his many works, a common motif is Isaac lying dead while the ram watches on, very much alive. His semi-abstract sculpture The Sacrifice of Isaac (1982-1985), displayed outside the Tel Aviv museum of art, depicts Isaac as a decapitated head lying dead on the ground with the ram looking down on him. Two grieving women stand at a distance. The survival of the ram and the death of Isaac can only be a catastrophe. This work was created as Kadishman’s response to the war in Lebanon (1982).[29]

This ram, for Kadishman, was a central protagonist of the Akedah and his art portrays the ram in a central role, with complex and shifting significance. As a young man Kadishman worked as a shepherd and was drawn to drawing animals.[30] But he has also described the ram as “a symbol of blind and cruel brutishness”[31] and as the source of fear and violence.[32]

In this context, Isaac represents the dead in war, or those who come near to death. As Kadishman declares in an interview: “My father was in the Haganah and I was in the army too: I was Isaac and he was Abraham. Now I am Abraham and my son became Isaac.”[33]

This generational sacrifice of sons to war is for Kadishman a horror that repeats through the generations. As Kadishman writes, “What is most frightening is that in every generation Isaac returns, and is again sacrificed. The ram will triumph over Isaac, the raven over innocence and the vulture over the fallen angel- each embodying the innocent Isaac.”[34] In his rendering here God is entirely absent and neither asked for the sacrifice nor will He intervene to stop it.[35]

For Kadishman, the Akedah is the opposite of redemption and religion. The Akedah is a pointless death. God is not present, did not ask for Isaac’s sacrifice and will not intervene to stop it.

October 7, 2023

Kadishman’s Tel Aviv piece took on a new life in the aftermath of the October 7, 2023 attacks, when the Israeli artist Keren Zach developed the new installation Pieces of Light, which was installed around the Kadishman work. In this installation, mirrors reflect both the viewer’s face and the sunlight, mirroring both the national trauma and the hope for survival.[36]

The juxtaposition of Pieces of Light and The Sacrifice of Isaac brings us back to the medieval tradition of the death of Isaac connecting to the grief of Isaac's descendants. Isaac represents the dead and the captured. The women who mourn Isaac are also mourning all the hostages and all the dead.

Pann, Chagall, Bak, Gershuni, and Kadishman, each in their different ways create something very new out of the story of the Akedah, with their shocking images of dead Isaac. Their work may even reject the presence of God in the story. Nevertheless, they draw on ancient traditions of using the Akedah to express grief and even anger and even sometimes the beginnings of hope. They ask, along with Isaac from the Tisha B’Av lament of Az Behaloch Yirmiyah: Was Isaac killed in vain?

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 25, 2025

|

Last Updated

January 6, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Rabbi Devorah Schoenfeld is Associate Professor of Theology at Loyola University Chicago, where she teaches Judaism, Bible, and Jewish-Christian Relations. Her PhD is from the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley (2007), and she has previously taught at University of California, Davis, at St. Mary’s College of Maryland and at the Conservative Yeshiva in Jerusalem. She received her rabbinical ordination from Yeshivat Maharat (2019). Her book, Isaac on Jewish and Christian Altars, compares Rashi and the Glossa Ordinaria on the akedah. She has also published on midrash, parshanut and interreligious relations.

Dr. Monika Czekanowska-Gutman is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Art History at the University of Warsaw. Her research focuses on twentieth-century Jewish art and culture in Israel and the America, and the contribution of modern Jewish artists to modern art. She has recently published a book by Brill based on her Ph.D. thesis on visual representations of Judith, Esther, and the Shulamite in modern Jewish art. She has also published in Ars Judaica, Images, and Religion and the Arts. Her current research project on depictions of the akedah as an actual sacrifice in modern and contemporary Jewish visual culture, funded by the National Science Centre, is being conducted in joint cooperation with Dr. Devorah Schoenfeld and Dr. Amitai Mendelsohn.

Essays on Related Topics: