Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Part 6

Scribal Marks

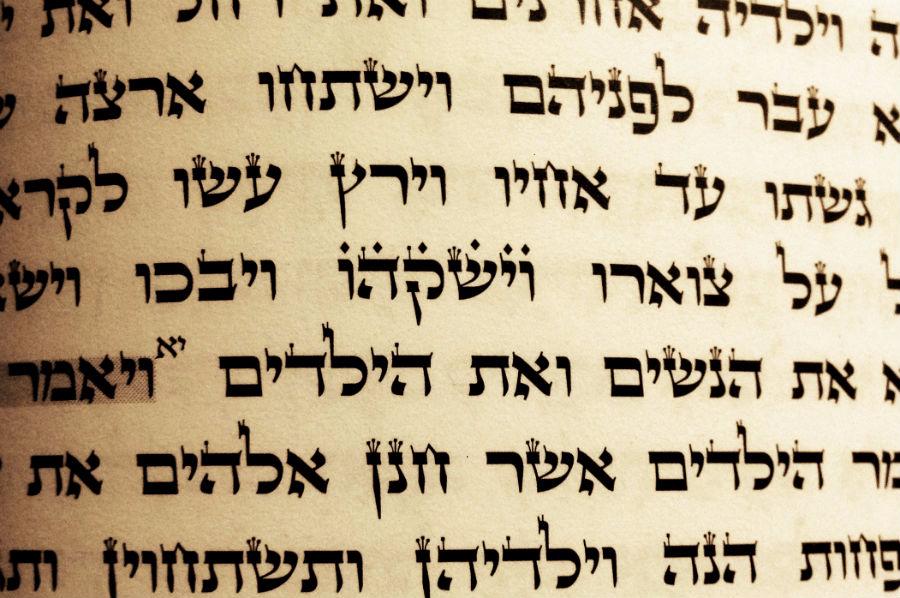

The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa), written ca. 125 B.C.E., is the largest and best preserved of all the Qumran biblical scrolls, whose 54 columns contain all 66 chapters of Isaiah. The picture is of the opening section. Note: In column 3, two corrections can be seen: 6 lines from the bottom, the word אדוני has dots below each letter, indicating a needed erasure, and above it is written י־הוה. The line below this shows the reverse, with the word י־הוה being corrected with dots and a supralinear insertion of the word אדוני.

The forerunners of the proto-MT scribes used several marks to communicate scribal information to later scribes. These practices were not invented by them for the copying of specifically biblical texts, but were used also in many of the biblical and nonbiblical texts found in the Judean Desert, including texts that did not have a Masoretic character.

Despite the intention of the original scribes who made these marks, the scribes of MT sanctified the totality of the written surface of the texts they copied, and thus included these scribal marks.

Puncta Extraordinaria

MT includes scribal dots under or above letters serving to denote letters that had been deleted by the scribes, as often occurring in the Dead Sea Scrolls. These dots were meant to delete details in the text because it was technically difficult to erase letters from a leather scroll, and these dots were not meant to be copied to the next scroll.

Because of the extreme care taken in copying MT, the dots that appeared in the text from which the proto-MT text was copied were now included in the new copies through the medieval texts and our printed editions.

By necessity, these dots had to be reinterpreted by the Masoretic tradition and they were now considered doubtful letters. Named “special dots” (puncta extraordinaria) within the Masoretic tradition, these dots, above the letters, show the strength of that tradition in preserving the smallest scribal details. For example:

Lot’s Older Daughter – MT has a dot over the waw of ובקוׄמה in Gen 19:33, which refers to when Lot’s older daughter arose after cohabiting with her father. The rabbis suggest that the dot teaches that although the verse says “he was not aware of her lying or rising” he was, in fact, aware of her rising. This makes his agreement to drink until intoxicated the next night much more problematic. The original meaning of the dot was simply to erase the letter and make the spelling defective, as it is with the description of the younger daughter rising in v. 35.[1]

Esau’s Kiss – Another example is the dots above the complete word וֹיׄשׄקׄהׄוׄ in Gen 33:4, which refers to Esau’s kissing of Jacob after the latter returns to Canaan. The rabbis suggest that the kiss was pretended or even that Esau tried to bite Jacob.[2] The dots more likely indicate that the word should be erased, although the original reason for this erasure is unknown. The word could have been lacking in another manuscript to which the text was compared.

Erasures and Additions: Evidence from Variants

In all such cases of puncta extraordinaria, the text can be maintained without the dotted letters that were originally meant to be erased. In fact, in a number of cases we can see that a word dotted in one text is missing from another.

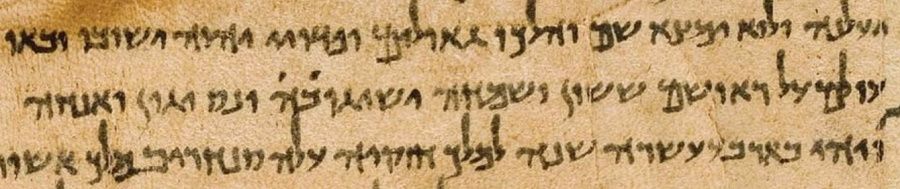

Dotted in Qumran and Missing in MT – Dots on top of letters to be erased occur frequently in 1QIsaa. The dots indicate that the original or later scribe of 1QIsaa was noting that a given letter or word should be removed by any scribe who would recopy this manuscript.

For example, Isa 35:10 in the scroll has dots over the letters בׄהׄ while MT does not have this word.

| MT | 4QIsaa | ||

| They shall attain joy and gladness, while sorrow and sighing flee. |

שָׂשׂוֹן וְשִׂמְחָה יַשִּׂיגוּ וְנָסוּ יָגוֹן וַאֲנָחָה

|

ששון ושמחה ישיגו בׄהׄ ונסו יגון ואנחה.

|

They shall attain joy and gladness in it, while sorrow and sighing flee. |

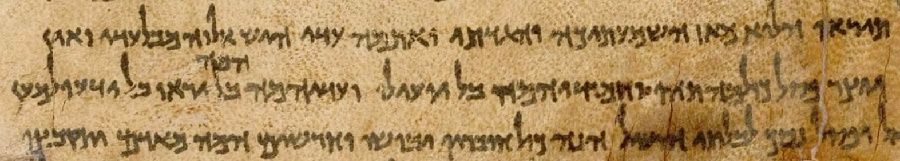

Dotted in MT and Added in Qumran – The word המה, in Isa 44:9, appears with three dots above it in MT.

יֹֽצְרֵי פֶ֤סֶל כֻּלָּם֙ תֹּ֔הוּ

וַחֲמוּדֵיהֶ֖ם בַּל יוֹעִ֑ילוּ

וְעֵדֵיהֶ֣ם הֵמָּ֗ה֗

בַּל יִרְא֛וּ

וּבַל יֵדְע֖וּ לְמַ֥עַן יֵבֹֽשׁוּ׃

The makers of idols all work to no purpose;

And the things they treasure can do no good,

As they can testify themselves.

They neither look nor think,

And so they shall be shamed.

The same word occurs in 1QIsaa as a supra-linear (above the line) addition without dots, signifying that it did not appear in the original text of the scroll but was added to it.

Dotted in MT and Absent in SP and Peshitta – In Num 3:39, MT has dots over the name Aaron:

במדבר ג:לט כָּל פְּקוּדֵ֙י הַלְוִיִּ֜ם אֲשֶׁר֩ פָּקַ֙ד מֹשֶׁ֧ה וְ֗אַ֗הֲ֗רֹ֛֗ן֗ עַל פִּ֥י יְ־הוָ֖ה לְמִשְׁפְּחֹתָ֑ם

Num 3:39 All the Levites who were recorded, whom at YHWH’s command Moses and Aaron recorded by their clans.

The dotted word is lacking in the Peshitta and SP, which shows that a textual tradition of a shorter text existed.

Inverted Nunim

The so-called inverted nunim (also named nunim menuzarot, “separated” or “isolated” nunim), found in manuscripts and printed editions before and after Num 10:35–36, are actually misunderstood scribal signs for the removal of inappropriate segments, viz., the Greek letters antisigma [ↄ] and sigma [C], known from Alexandria and the Qumran scrolls. The inverted nunim in this place indicated that these verses (the “Song of the Ark”) do not appear in their correct place, as is indeed indicated by a tradition in ’Abot R. Nat.[3] (Strange as it may seem, there was no exact indication where this verse should be placed.)

These examples highlight the method of the MT scribes who believed everything in the text needed to be copied “as is.” Since these details were not meant to be copied into a subsequent text, the fact that the MT scribes did so is important evidence for understanding their approach.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 8, 2017

|

Last Updated

December 23, 2025

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Emanuel Tov is J. L. Magnes Professor of Bible (emeritus) in the Dept. of Bible at the Hebrew University, where he received his Ph.D. in Biblical Studies. He was the editor of 33 volumes of Discoveries in the Judean Desert. Among his many publications are, Scribal Practices and Approaches Reflected in the Texts Found in the Judean Desert, Textual Criticism of the Bible: An Introduction, The Biblical Encyclopaedia Library 31 and The Text-Critical Use of the Septuagint in Biblical Research.

Essays on Related Topics: