Edit article

Edit articleSeries

The Transformation of Hebrew Script: From Paleo-Hebrew to Aramaic

Ktav Ashuri, כְּתָב אַשּׁוּרִי — the traditional “Square Script” Hebrew alphabet used for Torah scrolls, distinct from the older Paleo-Hebrew script.

With the revival of modern Hebrew, early Zionists debated in what script the language should be written. Vladamir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky and Itamar Ben-Avi argued that Hebrew should be written in Latin script, so that European Jews could learn it more easily. Nevertheless, most of other Zionist leaders wished to maintain what they believed to be the traditional Hebrew script.[1]

The modern Hebrew script has its own history, however. Ironically, it came to Hebrew from Aramaic script, having beaten out the original Old Hebrew script in what may have been an ancient iteration of the same debate the Zionists had in the early 20th century.

Exile to an Alphabetic Culture

When Judah was conquered by the Babylonians, the Judeans found themselves in exile in a kingdom that had adopted the Aramaic alphabet. While Akkadian had been the official language of Babylonia for centuries, by the sixth century B.C.E., it was mostly relegated to an elite language.[2] In its place, due to heavy immigration of Arameans south into Mesopotamia, Aramaic had gained dominance as the spoken language, and Assyrian and Babylonian kings employed scribes of both languages.

Akkadian was written in cuneiform, a complicated system of syllabic wedge signs, unreadable to anyone without scribal education. It was a medium most suited to clay tablets. Aramaic, in contrast, used letters written with ink in an alphabet similar but not identical to Hebrew—it could easily be written on papyrus or animal skins. Alphabets allow for a greater level of literacy than syllabic writing, and the Judeans, who were also used to using an alphabet, quickly adapted to the use of Aramaic writing, enabling them to take part in the economy and society.

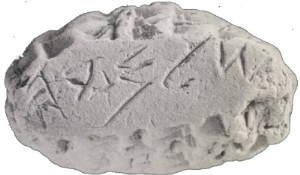

Nevertheless, Judeans in the Babylonian exile continued to use Old Hebrew script as well, especially when writing in Hebrew. A few cuneiform texts from the town of al-Yahudu (“the town of the Jews”), have edges inscribed with a label in Old Hebrew script.[3]

Some Judeans used a hybrid form of writing. For example, a seal belonging to “Yehoyishma‘ daughter of Šawas-śar-uṣur” (יהוישמע בת שוששראצר) uses Old Hebrew script, with distinctive Hebrew heh, vav, and mem, for the Hebrew name Yehoyishma‘, but Aramaic script, with distinctive ‘ayn, vav, and ṣade, for the Babylonian name of her father.[4] This eclectic and inconsistent use of the two available alphabets is not surprising in a situation where the only reason for the switch is acculturation.

Persian Imperial Writing

The importance of Aramaic script changed with the transition to Persian rule in 539 B.C.E.[5] Although Persians had their own language and script—alphabetic cuneiform—they instituted strict scribal training in Aramaic writing throughout the empire in centrally-run chancelleries. Local scribal traditions were bulldozed by the administrative monopoly. By the fifth century, scribes from the southwestern corner to the northwestern frontier were writing Aramaic in precisely the same way.

The bureaucracy that governed more territory than any empire previously in human history relied on smooth systems of communication throughout, as encapsulated both in the book of Esther and in Herodotus’s fawning description:

Herodotus Histories 8:98 Nothing stops these couriers from covering their allotted stage in the quickest possible time—neither snow, rain, heat, nor darkness.[6]

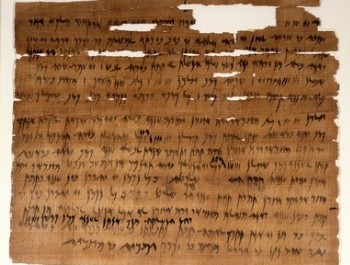

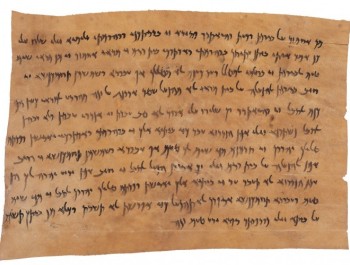

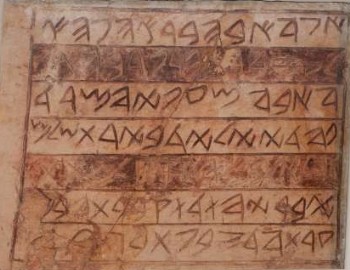

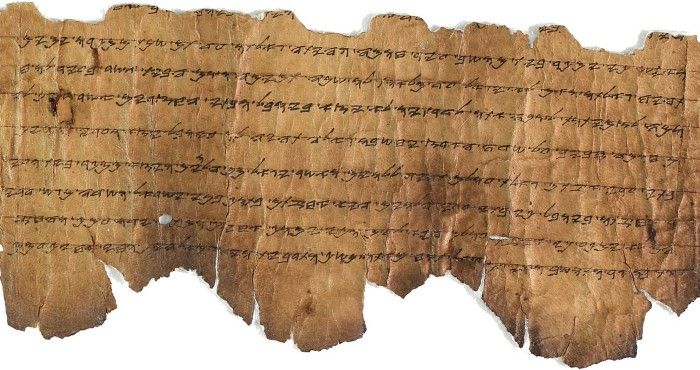

Under this pressure, Judeans exiles, too, began to change their writing habits—at least on the level of official administration and bureaucracy.[7] The similarity in writing practices between different parts of the empire may be seen by comparing the writing on the left, from the Judean garrison in Elephantine, to the writing on the right, from the area of Balkh, Bactria, in northern Afghanistan – more than 2000 miles away as the crow flies:

|

|

|

Aramaic marriage contract on papyrus from Elephantine, 5th century B.C.E. Brooklyn Museum |

Aramaic letter from Bactria 4th century B.C.E. Naveh and Shaked Khalili collection |

This level of uniformity could only be the result of centralized pressure to homogenize scribal practices across the empire. We have no papyri from Judea, but some are found from neighboring Samaria. Here, in the fourth century, scribes were writing in a “beautiful Aramaic cursive”:[8]

Only official writing, such as legal documents, were subject to imperial pressure toward uniformity, so people still used other scripts in other circumstances. Thus, together with these Aramaic documents, a bulla (seal) inscribed in Old Hebrew script was found, indicating that it belonged:

[לדל]יהו בן [סנא]בלט פחת שמרן.

To Delyahhu son of Sanballat, governor of Samaria. [9]

|

|

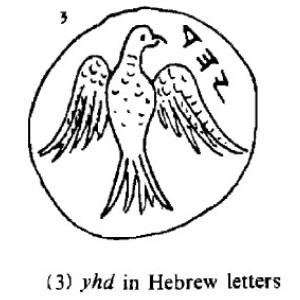

Perhaps more surprising, coins with the legend yhd “Yehud,” the Aramaic name for the province of Judea, are found in both Hebrew (usually) and Aramaic (occasionally) scripts:[10]

|

|

In sum, the Persians were not interested in controlling Hebrew writing meant for internal consumption, and thus, throughout the Persian period, Hebrew texts were still written in Old Hebrew script,[11] but Aramaic writing had already entered into Judean culture as the dominant script, given that people spoke Aramaic as their vernacular.

Old Hebrew Persists under Greeks and Romans

With the dismantling of the Persian imperial apparatus after Alexander in the late fourth century B.C.E., the centralized bureaucracy and chancellery disintegrated, and local polities were again free to write as they wished. Indeed, the native, Old Hebrew script persisted in use throughout the following centuries, for example, in this remarkable seven-line Aramaic(!) inscription from Giv‘at ha-Mivtar in Jerusalem, from the last century of the Second Temple period:[12]

אנה אבה בר כהנה אלעז בר אהרן רבה אנה אבה מעניה מרד פה די יליד בירושלם וגלא לבבל ואסק למתתי בר יהוד וקברתה במערתה דזבנת בגטה

I, Abba, son of the priest Eleaz(ar), son of Aaron the Great – I, Abba, the oppressed, the pursued, who was born in Jerusalem and went to exile in Babylonia; I brought up Mattatya son of Yehud, and buried him in the grave which I purchased by document.

Some scholars see each instance of Old Hebrew script as an act of ideological significance, of resistance to the newer and homogenizing Aramaic script, perhaps of nationalistic significance.[13]

In this case, Yoel Elitzur has argued that the ossuary contained the bones of Mattathias Antigonus, the last Hasmonaean king. When Herod besieged Jerusalem, Antigonus was taken to Antioch. Abba, the writer of the inscription, brought back Antigonus’ body after his ignominious death and buried him in Jerusalem.

The significance of the figure and the patriotic act of his burial would explain why the inscription focuses on the act of burial rather than the person interred, and why a priest, normally forbidden from coming in contact with a corpse, would have defiled himself in this way.[14] The patriotism may have also dictated the choice of script. Abba apparently chose a “modern” version of the Old Hebrew script. Later on this became associated with the Samaritans, but in Roman times it doesn’t seem to have been ideological.[15]

Aramaic and Old Hebrew Script in Scrolls

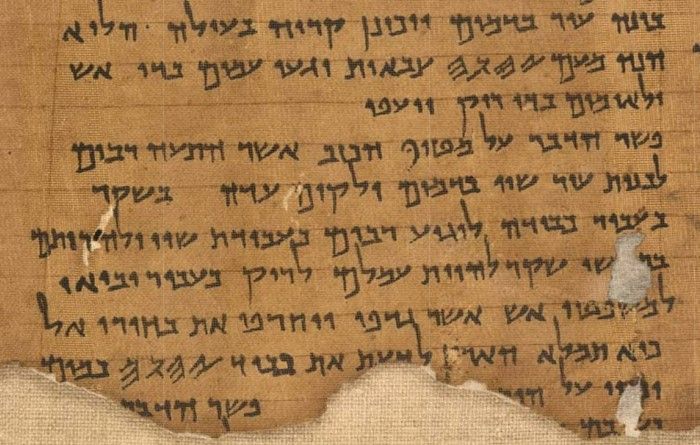

During the Greco-Roman period, the use of Aramaic script grew from legal and official texts to all types of writing, eventually becoming the usual way of Jews writing both Aramaic and Hebrew texts. Though it is not possible to know to what extent the sectarian corpus at Qumran is representative of the state of affairs in Roman-era Jewish society more broadly, the Dead Sea Scrolls are overwhelmingly in the Aramaic script, used for both biblical and other books. That said, several trends stand out:

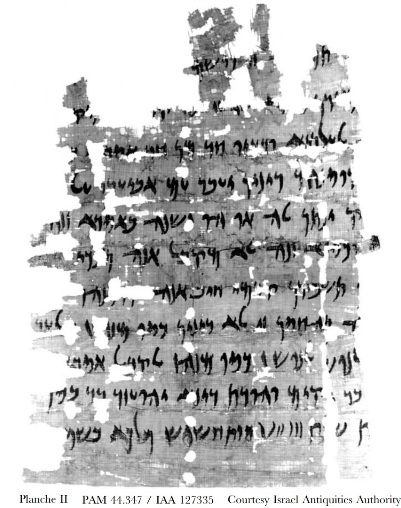

Old Hebrew for the Tetragrammaton—In several scrolls, the divine name YHWH is written in the Old Hebrew script even though the rest of the text uses the Aramaic script (see if you can spot it):

The Qumran community may have held, like the Rabbis (Mishnah Yadayim 4:5; see below), that biblical texts were only sacred if written in the now-usual Aramaic script, and they wished to avoid the problems of sacred texts. More likely, however, the scribes felt that divine names were too sacred for the new script.[16]

Old Hebrew Scrolls—A little over a dozen Qumran scrolls are in Old Hebrew script. The texts are all Pentateuchal books or Job.[17] These are not the oldest texts in Qumran, which date from the third century B.C.E. Instead, the Old Hebrew scrolls were all produced well into the Roman period, the first century B.C.E. and even the first century C.E.

Writing in Old Hebrew was not merely a question of choice of scripts, but it came with an entire suite of scribal practices. For example, Old Hebrew almost always divides words by dots, whereas Aramaic script divides words by spaces.[18] Old Hebrew texts split words between lines; Aramaic script texts never do.

Coins—As noted above, coinage consistently used the Old Hebrew script for dates and other labels: this is true of coins minted by the Hasmoneans, under the Great Revolt, and by Bar Kokhba. This is often understood as an artificial use for nationalistic purposes, but the fact that Old Hebrew script was still in use undercuts this claim to some extent.[19]

The Disappearance of Old Hebrew for Jews

Perhaps helped by the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E. and the catastrophe of Bar Kokhba’s revolt in the 130s, Old Hebrew script was no longer used among Jews by the end of the second century. In fact, the Mishnah rules that a Torah scroll written in Old Hebrew script is not valid:

משנה ידים ד:ה וכתב עברי אינו מטמא את הידים. לעולם אינו מטמא עד שיכתבינו אשורית על העור בדיו.

m. Yadayim 4:5 And Hebrew script does not defile the hands.[20] It does not defile the hands until one writes it in Aramaic script on parchment with ink.

As Joseph Naveh observed, this seems surprising:

We are faced with an extraordinary phenomenon: the Jews, a conservative nation which adhered to its traditional values, abandoned their own script in favour of a foreign one.[21]

Naveh suggests that Old Hebrew script had become associated with certain groups of Jews, particularly the Sadducees and the Samaritans, and so the Pharisees opposed Old Hebrew script, and the rabbis, being their continuation, inherited this.[22] An alternative is that by the time the Persians disappeared from view, the Aramaic script had become nativized, and was not seen as foreign to most Jews. By the time that scribe first put pen to papyrus(?) to write the first Aramaic-script Torah, the script had been in use among Jewish circles for many centuries. So although the Torah had never been written this way, it may have seemed natural that it would be. And so it was.

Rabbinic thought about כתב עברי

Although we have seen in the previous section that the transition from Hebrew script to Aramaic script was (a) slow, (b) inconsistent, and (c) pragmatic rather than ideological, in hindsight it appeared to Jews to have been momentous. In 4 Ezra, a pseudepigraphic text from the first century C.E., Ezra reports that God sent him to the wilderness with five skilled scribes. After being given a supernatural drink, the scribes began to take dictation:

By turns they wrote what was dictated, in characters which they did not know. They sat forty days, and wrote during the daytime, and ate their bread at night. As for me, I spoke in the daytime and was not silent at night. So during the forty days, ninety-four books were written. And when the forty days were ended, the Most High spoke to me, saying, “Make public the twenty-four books that you wrote first and let the worthy and the unworthy read them; but keep the seventy that were written last, in order to give them to the wise among your people. For in them are the springs of understanding, the fountains of wisdom, and the river of knowledge.”

The portrait of Ezra as a second Moses is clear here.[23] The reference to the scribes in Ezra’s day writing “in characters which they did not know” seems to be a way of explaining why the script changed in his day – and also a way of denying that the script was borrowed from a foreign source.

The Rabbis of the following century shared in the concern over the legitimacy of the new script. As Shlomo Naeh put it, “The change of script presented the Rabbis with a difficult exegetical and ideological challenge from a number of angles. They were forced to concede, against the principle of continuity that they normally trumpeted, that the Torah in their own hands was different in form and appearance from that given through Moses. This concession was particularly difficult because the Rabbis sanctified every detail of the script in their hands.”[24]

The Rabbis formulated different views over how to understand this. These are most clearly expressed in the Tosefta:[25]

תוספתא סנהדרין ד:ז ר' יוסה אומר: ראוי היה עזרא שתנתן תורה על ידו, אילמלא קידמו משה. ...

t. Sanhedrin 4:7 Rabbi Yose says: “Ezra was worthy of having the Torah given through his hand, had not Moses preceded him.” …

ר' אומר בכתב אשורי נתנה תורה לישראל, וכשחטאו נהפכה להן לדחץ, וכשזכו בימי עזרא חזרה להן אשורית....

Rabbi [Judah ha-Nasi] says, “The Torah was given to Israel in Aramaic script, and when they sinned [at the Golden Calf] it was changed for them to the Hebrew script [daḥatz],[26] and when they again merited in the days of Ezra, it returned for them to Aramaic script. …

ר' שמעון בן לעזר או' משם ר' אליעזר בן פרטא שאמ' משם ר' אלעזר המודעי, בכתב זה ניתנה תורה לישראל.

Rabbi Shim‘on b. Elʿazar says in the name of Rabbi Eliʿezer b. Parṭa, who said in the name of Rabbi Elʿazar ha-Modaʿi: “The Torah was given to Israel in this script.”

For Rabbi Shimʿon b. Elʿazar, there is no problem, because the history is denied: for him, the Torah has always been in the Aramaic script. Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi offers a more complicated history. For him, the Torah was always meant to be in Aramaic script, and was originally in Aramaic script, but the Old Hebrew script was introduced as a punishment for the sin of the Golden Calf. Only with the return to the meritorious status in the age of Ezra was the Aramaic script restored to the Jews. This view has the advantage of crediting Ezra with actions that led to the revision of the script of the Torah. Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi does not explain why the Hebrew script should be a punishment, or what is so special about the Aramaic script that the Jews had to “merit” it.

The most radical view, however, is that of Rabbi Yose. He takes the bull by the horns and leaves the transition in place; for him, the Torah was in the Old Hebrew script until Ezra’s time, and then it was changed to Aramaic script. The major innovation in Rabbi Yose’s opinion is that this ought not bother us, because of Ezra’s involvement. The person of Ezra – worthy, indeed, of having received the Torah to begin within – is certainly a sufficient authority for the change of script. So while the transition is shocking, it is not a problem.

Another element in rabbinic thought seems to build on the view of Rabbi Yose. Not only is it acceptable (because of the authority of Ezra) that the script changed, but it is preferable:[27]

בבלי סנהדרין כא: אמר רב חסדא אמר מר עוקבא: "בתחלה ניתנה תורה לישראל בכתב עברי ולשון קודש. כיון שעלו בני הגולה בימי עזרא ניתנה להם בכתב אשורי ולשון ארמאי. וביררו להן ישראל כתב אשורי ולשון קדש, והניחו להן להדיוטות כתב עברי ולשון ארמי."

b. Sanhedrin 21b Rav Ḥisda said in the name of Mar ‘Uḳva: “At the beginning, the Torah was given to Israel in the Hebrew script and the Holy Language. Once the exilic community came up in the days of Ezra, the Torah was given to them in the Aramaic script and Aramaic language. Israel chose for themselves the Aramaic script and Hebrew language, and left the Hebrew script and Aramaic language for the fools.

מאי הדיוטות? אמר רב חסדא, "כותאיי."

Who are the fools? Rav Ḥisda said, “The Samaritans.”

מאי כתב עברי? אמר רב חסדא, "כתבא לבונאה."

What is the Hebrew script? Rav Ḥisda said, “The Neapolitan script.”

The fools are the Samaritans, who never did adopt the Aramaic script, and continue to write in a descendant of the Old Hebrew script to this day, and in fact “Hebrew script” is identified as “the script of Neapolis,” the name of the city now called Nablus.[28] Thus the adoption of the Aramaic script, rather than indicating that the Jews became like others, serves to differentiate them from their neighbors and cultural rivals, the Samaritans.

Other sources reflect on the question of the original script from other angles. For example, a tradition claims that the Ten Commandments were carved all the way through the tablets on which they were written. For a letter that includes a full circle, though, this creates a physical problem, as the center would simply fall out. Which letters would this affect?

The Eretz Israel tradition records:

ירושלמי מגילה א:ט אמר רבי לוי מאן דאמר לרעץ ניתנה התורה, עי"ן מעשה ניסים. מאן דאמר אשורי ניתנה התורה סמ"ך מעשה ניסים.

Rabbi Levi said: “According to the view that the Torah was given in Old Hebrew script (raʿatz/daʿatz), the ‘ayin was a miracle. According to the view that the Torah was given in Aramaic script, the samekh was a miracle.”

The Old Hebrew ‘ayin was indeed a circle, much like the samekh in the Aramaic script.

|

ס |

|

|

Old Hebrew ‘ayin |

Aramaic script samekh |

Interestingly, despite the various views already seen on the question of the original script, the parallel in the Babylonian Talmud does not include the possibility that the script was anything other than Aramaic script.[29]

Mystical Speculations about Letter Shapes: Block Script

None of these discussions prevented the Rabbis from engaging in mystical speculation about the shapes of the letters. In the following two examples, the shapes of the bet and the heh suggest to the midrashists that these particular letters made them appropriate to serve as the first letter of the world and the Torah:

בראשית רבה א:י ר' יונה בשם ר' לוי: למה נברא העולם בב'? מה ב' זה סתום מצדדיו ופתוח מלפניו, כך אין לך רשות לדרוש מה למעלה ומה למטה ומה לאחור...אלא מיום שנברא העולם ולהבא.

Gen Rab 1:10 R. Jonah [said] in the name of R. Levi: Why was the world created with the ב? [To teach that] just as the ב is closed on all three sides and open only in the front, so does one not have the right to inquire about what is above and what is below…but only about time since the day the world was created.[30]

...ומה הא זה סתום מכל צדדיו ופתוח מלמטן, רמז שכל המתים יורדין לשאול, ועוקצו הזה שלמעלה רמז שהן עומדין לעלות, והחלון הזה שמן הצד רמז לבעלי תשובה.

[This world was created with the letter he.] Just as the he is closed on all its sides and open on the bottom – this hints at all people who die, who descend to Sheol; this pointy thing at the top – this hints that they will all rise again; this window on the side – this hints at those who repent.

והעולם הבא נברא ביוד, ומה יוד זה קומתו כפופה כך הן הרשעים קומתן כפופה ופניהם מקדירות לעתיד לבא.

And the World to Come was created with the letter yod: just as the yod is bent over, so too the wicked are bent over, and their faces darkened in the Future.[31]

It is remarkable that the Rabbis engaged in this type of interpretation without any comment that the bet and the heh actually may have originally looked very different.

|

Old Hebrew shape |

Aramaic script |

|

ב |

|

|

ה |

|

|

י |

The Block Script Prevails

After the Roman period, Jewish writing takes different turns. In the Middle Ages, Jews in Spain, Germany, and Egypt spoke different languages, but all of them – Ladino, Yiddish, and Judeo-Arabic – were written in Hebrew script. With the revival of modern Hebrew, there was discussion as to what script to write it in.

Jabotinsky and Itamar Ben-Avi wanted Hebrew to be written in Latin script so that European Jews could learn it more easily. But the case for Hebrew script won. It was not a pragmatic case, but one steeped in thousands of years of history. For two millennia and through its diverse and varied forms, the script has become a marker of Jewish identity.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 29, 2025

|

Last Updated

February 10, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Aaron Koller is professor of Near Eastern studies at Yeshiva University, where he is chair of the Beren Department of Jewish Studies. His last book was Esther in Ancient Jewish Thought (Cambridge University Press), and his next is Unbinding Isaac: The Akedah in Jewish Thought (forthcoming from JPS/University of Nebraska Press in 2020); he is also the author of numerous studies in Semitic philology. Aaron has served as a visiting professor at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and held research fellowships at the Albright Institute for Archaeological Research and the Hartman Institute. He lives in Queens, NY with his wife, Shira Hecht-Koller, and their children.

Essays on Related Topics: