Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Who Was “Shelah Son of Judah” and What Happened to Him?

Judaeans sent into exile after the Assyrian capture of Lachish, Lachish Reliefs, ca. 700-692 BCE. Wikimedia

The Literary Exposition: The Judah and Tamar Story in Its Narrative Context

The story of Judah and his sons (Gen 38) is a recognized insertion in the Joseph cycle (Gen 37-50) that concludes the Book of Genesis. [1] The many literary parallels between the two stories indicate that they were meant to be read as one unit. This composition is reinforced by the Wiederaufnahme (the resumptive repetition)[2] in ch 37: 36 and 39:1 which is a biblical means of indicating a departure from and a return to the main narrative):

לז:לו וְהַמְּדָנִים מָכְרוּ אֹתוֹ אֶל-מִצְרָיִם לְפוֹטִיפַר סְרִיס פַּרְעֹה שַׂר הַטַּבָּחִים.

37:36 The Medanites, meanwhile, sold him in Egypt to Potiphar, a courtier of Pharaoh and his chief steward.

לט,א וְיוֹסֵף הוּרַד מִצְרָיְמָה וַיִּקְנֵהוּ פּוֹטִיפַר סְרִיס פַּרְעֹה שַׂר הַטַּבָּחִים אִישׁ מִצְרִי מִיַּד הַיִּשְׁמְעֵאלִים אֲשֶׁר הוֹרִדֻהוּ שָׁמָּה.

39:1 When Joseph was taken down to Egypt, a certain Egyptian, Potiphar, a courtier of Pharaoh and his chief steward, bought him from the Ishmaelites who had brought him there.

Tamar and Potiphar’s Wife

Both stories feature the seduction or attempted seduction of the main character. Here another contrast is introduced between two women, motivated by different desires, who use their feminine wiles to entrap the hero. The wife of Potiphar seeks sexual pleasure and domination over Joseph the foreign slave, while Tamar endangers her life in order to conceive children who will become the mainstay of the tribe of Judah.

Echoing the deeds of the brothers in bringing Joseph’s blood stained coat as proof of his death (Gen. 37:32-33), each of these women uses the garments or personal items of the hero as supportive evidence to prove their innocence. The villainous Mrs. Potiphar[3] presents Joseph’s raiment as proof of her claim of his rapacious intention, while the heroic Tamar displays the staff and stringed seal [4](חותם ופתילים) of the unidentified father of her unborn. Her act of kindness not to embarrass Judah,[5] and his admission of guilt allow him to rise to moral stature worthy of his future position of authority. Tamar is vindicated. Her noble character becomes a matriarchal model for later generations (Ruth 4:12).

Personal Seals

Another point of comparison between the stories is the motif of the signet ring which reflects the realia. Judah’s hotam obviously bears no identifying marks nor inscribed name. It was probably a stringed cylinder seal of the so-called plain Hurrian type which had geometric designs that was common in Canaan of the second millennium BCE.[6] This is compared to the other type of signet the tabb`at (41:42) or stamp seal that was common in ancient Egypt and did bear identifying signs.

Linguistic Similarities

On the linguistic level, both stories use the same roots at crucial moments:

- י.ר.ד “to go down” – Joseph goes down to Egypt (39:1) and Judah goes down from his brothers (38:1).[7]

- נ.כ.ר “to recognize” – The brothers ask Jacob to “recognize” the strip of Joseph’s bloody clothing (37:32) and Tamar asks Judah to “recognize” his staff and stringed seal (38:25).[8]

Placing Judah Opposite Joseph

These literary parallels between the Joseph and Judah stories imply that the stories were meant to be read in light of each other, with Judah functioning as a foil to Joseph. The significance of a Joseph-Judah comparison lies in the fact that in the monarchic period, these two tribes contended for dominance over their brother Israelite tribes.

The predominance of these two tribes is expressed most clearly in 1 Chron (5:1-2):

א וּבְנֵי רְאוּבֵן בְּכוֹר יִשְׂרָאֵל כִּי הוּא הַבְּכוֹר וּבְחַלְּלוֹ יְצוּעֵי אָבִיו נִתְּנָה בְּכֹרָתוֹ לִבְנֵי יוֹסֵף בֶּן יִשְׂרָאֵל וְלֹא לְהִתְיַחֵשׂ לַבְּכֹרָה. בכִּי יְהוּדָה גָּבַר בְּאֶחָיו וּלְנָגִיד מִמֶּנּוּ וְהַבְּכֹרָה לְיוֹסֵף.

1 The sons of Reuben the first-born of Israel. (He was the first-born; but when he defiled his father’s bed, his birthright was given to the sons of Joseph son of Israel, so he is not reckoned as first-born in the genealogy; 2 though Judah became more powerful than his brothers and a leader came from him, yet the birthright belonged to Joseph.)

Historical Memories in the Judah and Tamar Story

The Judah pericope in Gen 38 incorporates historic memory of the proto-history of the tribe of Judah as well as pre-Deuteronomistic versions of family law.

Legal Differences

Levirate marriage (from the Latin word levir, meaning “husband’s brother”) – this institution safeguards the childless widow within the tribal framework. According to Deuteronomy 25:5-10, this duty falls on the surviving brother in law (Deut 25:5-10). In the story of Judah, however, the responsibility falls not only on the brother of the deceased, but on other males in the family, in this case the father.[9] This likely reflects the old tribal institution of the go’el, as seen in the Book of Ruth.[10]

Burning an adulteress – Judah declares Tamar’s punishment to be execution by fire, a punishment limited in the Torah (Lev. 21:9) to a daughter of a kohen.[11]

From Pastoralist to Farmer

Judah is depicted as pastoralist continuing the unsettled life of a sheep and goat herder of an earlier Patriarchal generation. He socializes with and takes two wives from the local Canaanite population.[12] It is only in Jacob’s blessing at the end of the book (Gen. 49:11) that signals the social and economic change associated with the later highland tribe known for its vineyards and farmers, descendants of Tamar’s progeny Peretz and Zerah.

Shelah: Names and Geography

With this background in mind, we can turn to Judah’s third and silent son, Shelah a relatively minor figure in the story, who does not marry Tamar to father children for his deceased brothers. However, he plays a significant role in this narrative as a game changer in that his passivity induces Tamar to take matters into her own hands. Shelah already stands out among his brothers in that we have an added bit of information regarding his birthplace Achzib (38:5).

וְהָיָה בִכְזִיב בְּלִדְתָּהּ אֹתוֹ

He was at Chezib when she bore him.[13]

Chezib/Achzib—not to be confused with the northern coastal city of the same name—likely refers to a town in the vicinity of Mareshah. Etymologically, the toponym Chezib/Achzib should be derived from the root kzb meaning “luxuriant.” It is related to the Akkadian kuzbu, “luxuriance, charm, sexual vigor,” which is probably behind the name of the temptress Kozbi bat Zur (Num. 25:15, 18). In this story the name is meant to imply the homophonous root כזב kđb (Aram. kdb; Arab. ک ذ ب) “falsehood.” The same word play can be found in Micah 1:14:

בָּתֵּי אַכְזִיב לְאַכְזָב לְמַלְכֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל.

The houses of Achzib are to the kings of Israel like a spring that fails.

The name Shelah is likely meant to bring to mind the word שלו “disappointment” (see, e.g., 2Kings 4:28). As the Latin saying goes, “a name is a sign” (nomen est omen). In the story, the disappointment is that Shelah never marries Tamar and fathers sons for his deceased brothers. Historically speaking, Shelah may be a disappointment as they are the clan that lost prominence in comparison with the stronger clans of Peretz and Zerah, as we shall see.

The story of Judah and Tamar takes place in a very specific swath of Judean territory, namely the Judean Shephelah. We see this from the place names it uses, Adulam, Achzib, Einaim, Timnah, all of which can be located in the Shephelah, between the valleys of Elah and Soreq, and three of which are mentioned specifically in the list of cities in the Shephelah found in Joshua 15:37-44: Enam (=Einaim), Adullam, and Achzib (Chezib).[14] Weaving these place names into the narrative not only gives the story a realistic sense, but also locates the founding father of the tribe, Judah, in the home territory of the descendants of Shelah.

The Genealogy of Shelah in Chronicles

We can trace the history of Shelah using his genealogy as preserved in 1Chron 4:21-23.[15] Its placement at the end of the section on Judah (chs 2:1-4:23) indicates Shelah’s inferiority in the eyes of the Chronicler with respect to his younger brothers:

בְּנֵי שֵׁלָה בֶן יְהוּדָה: עֵר אֲבִי לֵכָה (לכיש) לַעְדָּה אֲבִי מָרֵשָׁה מִשְׁפְּחוֹת בֵּית-עֲבֹדַת הַבֻּץ לְבֵית אַשְׁבֵּעַ. וְיוֹקִים וְאַנְשֵׁי כֹזֵבָא יוֹאָשׁ וְשָׂרָף אֲשֶׁר בָּעֲלוּ לְמוֹאָב וְיָשֻׁבִי לָחֶם (לחמס) וְהַדְּבָרִים עַתִּיקִים הֵמָּה הַיּוֹצְרִים וְיֹשְׁבֵי נְטָעִים וּגְדֵרָה עִם-הַמֶּלֶךְ בִּמְלַאכְתּוֹ יָשְׁבוּ שָׁם.

21 The sons of Shelah son of Judah: Er father of Lecah, Laadah father of Mareshah, and the families of the linen factory at Beth-ashbea; 22 and Jokim, and the men of Cozeba, and Joash and Saraph, who married into Moab and residents of Lehem (the records are ancient). 23 These were the potters who dwelt at Netaim and Gederah; they dwelt there in the king’s service.

This list preserves important details regarding the settlement of the Shelah clan and especially about their economic dependence on royal patronage, probably during the reign of Hezekiah. The fact they there were in the king’s service highlights their strategic importance on the Philistine border. (For a detailed analysis of this pericope, see appendix.)

The Shephelah was conquered by Senacherib in 701 BCE in his campaign against Hezekiah.[16] This is described in 2 Kings 18-20, but also in the words of the prophet Micah HaMorashti who was a resident of the area and possibly a Shelanite himself. Micah 1:10-15 describes with ironic force the destruction and exile of the local Judeans.

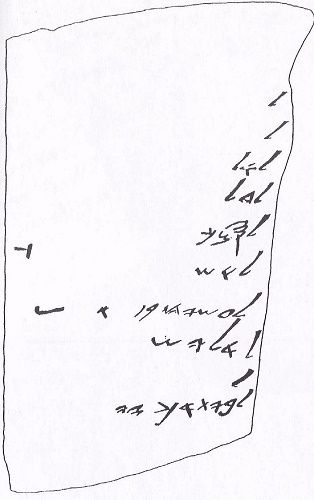

The reference in verse 14b (quoted above) to the “Houses of Achzib that will be a disappointment to the Kings of Israel (i.e. Judah)” (בָּתֵּי אַכְזִיב לְאַכְזָב לְמַלְכֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל) fits well with what we see in the above genealogy, i.e., that these “houses” were village installations for royal works.[17] It is noteworthy that Micah’s phrase “Houses of Achziv” (בתי אכזיב) was discovered, inscribed in the singular, on an ostracon in the excavation at Lachish. After listing a number of people plus numbers, it ends with the summary statement [לביתאכז[יב, i.e. “belonging to the house of Achz[ib].[18]

The reference in verse 14b (quoted above) to the “Houses of Achzib that will be a disappointment to the Kings of Israel (i.e. Judah)” (בָּתֵּי אַכְזִיב לְאַכְזָב לְמַלְכֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל) fits well with what we see in the above genealogy, i.e., that these “houses” were village installations for royal works.[17] It is noteworthy that Micah’s phrase “Houses of Achziv” (בתי אכזיב) was discovered, inscribed in the singular, on an ostracon in the excavation at Lachish. After listing a number of people plus numbers, it ends with the summary statement [לביתאכז[יב, i.e. “belonging to the house of Achz[ib].[18]

The conquest of the Shephelah’s most powerful city, Lachish, is depicted in the famous wall carving (below) found in the Assyrian king’s throne room in Nineveh and now displayed in the British museum.

It is quite likely that one Shelanite family escaped this fate and found refuge in Jerusalem. This is reflected in the late books of Chronicles and Nehemiah:[19]

1Chronicles (9:5)

וּמִן-הַשִּׁילוֹנִי

עֲשָׂיָה הַבְּכוֹר וּבָנָיו

And of the Shilonites:

Asaiah the first-born and his sons.

Nehemiah (11:5)

וּמַעֲשֵׂיָה בֶן-בָּרוּךְ בֶּן-כָּל-חֹזֶה בֶּן-חֲזָיָה בֶן-עֲדָיָה בֶן-יוֹיָרִיב בֶּן-זְכַרְיָה בֶּן-הַשִּׁלֹנִי.

And Maaseiah son of Baruch son of Col-hozeh son of Hazaiah son of Adaiah son of Joiarib son of Zechariah son of the Shilonite.

Bringing It Together: The Life and Death of Shelah

By bringing together the different genres of biblical literature including narrative, prophetic poetry as well as genealogical and geographical lists in addition to extra biblical epigraphic and iconographic sources, I have tried to reconstruct the historic impact of this son of Judah and his progeny during the ensuing biblical period as follows:

Shelah was once an important clan of Judah, dwelling in the Shephelah. During the time of King Hezekiah and perhaps earlier, they functioned both as an economic tool for the king, producing cloth and pottery, as well as maintaining a Judahite presence on the Philistine border. In 701, they were destroyed and the survivors fled to Jerusalem and were integrated into the community of Jerusalem.

Appendix

Phrase by Phrase Commentary on the Shelah Pericope (1Chronicles 4:21-23)

בְּנֵי שֵׁלָה בֶן-יְהוּדָה: עֵר אֲבִי לֵכָה (לכיש) לַעְדָּה אֲבִי מָרֵשָׁה מִשְׁפְּחוֹת בֵּית-עֲבֹדַת הַבֻּץ לְבֵית אַשְׁבֵּעַ. וְיוֹקִים וְאַנְשֵׁי כֹזֵבָא יוֹאָשׁ וְשָׂרָף אֲשֶׁר-בָּעֲלוּ לְמוֹאָב וְיָשֻׁבִי לָחֶם (לחמס) וְהַדְּבָרִים עַתִּיקִים הֵמָּה הַיּוֹצְרִים וְיֹשְׁבֵי נְטָעִים וּגְדֵרָה עִם-הַמֶּלֶךְ בִּמְלַאכְתּוֹ יָשְׁבוּ שָׁם.

21 The sons of Shelah son of Judah: Er father of Lecah, Laadah father of Mareshah, and the families of the linen factory at Beth-ashbea; 22 and Jokim, and the men of Cozeba, and Joash and Saraph, who married into Moab and residents of Lehem (the records are ancient). 23 These were the potters who dwelt at Netaim and Gederah; they dwelt there in the king’s service.

Er father of Lecah – According to this genealogy, Shelah named his oldest son Er, ostensibly after his dead brother. This is an ironic turn for according to Genesis he was supposed to have fathered a child with Tamar and named him after his brother so as to preserve his memory in his tribal inheritance. Looking at the matter from a tribal as opposed to familial perspective, this may signify a remnant of a declining Er family that joined the Shelanites. In any case, Er is the Clan-Father of Lechah,[20] a biform of Lachish, the primary city in the area.

Laadah father of Mareshah – The second town in importance is Mareshah, which was led by Shelah’s second son La`adah. This hierarchy is confirmed in the archaeology of these two major sites in the Shephelah—Maresha was a significant city, but not as significant as Lachish—and implies that these two powerful cities identified themselves with the Shelanites.

Families of Beth Ashbea – The next offspring are not named, but described as families that worked on the byssus clothe, a highly valued flax that was imported from Egypt and used to make clothing for the priesthood and for the aristocracy. The town associated with this village occupation was Beth Ashbea. Perhaps Ashbea ((אשבע with prosthetic alefand the interchange of the labials (compare Bath-Sheba/Shua , I Chron 3:5) preserves the personal name Shua (שוע), the maternal patriarch of Shelah (Gen 38:2).

Jokim of the people of Cozeba – The next is a clan head Yokim of the people of Kozeba, which is obviously another name for Achzib, located near Mareshah.

Joash and Saraph – These are two other members of the family who moved to/or worked for the Moabites.

Residents of Lahem – Concluding this list are the residents of Lahem or Lahmas (ibid v. 40).

Colophon: Potters in the Kings’s Service – The list ends by saying that it is “old” or “copied,” followed by two explanatory notes whose relationship to each other is unclear: “These were the potters who dwelt at Netaim and Gederah” and “They dwelt there in the king’s service.” The latter note implies that these cities and villages bordering the Philistine city-states were under the king’s patronage some of them housing installations working in specialties like producing garments made from the imported luxury byssus for the Judean aristocracy. Others were the potters making the storage jars bearing the royal lmlk (to/of the king) seal. Neutron activation analysis (analysis of clay type) of these storage jars indicates that they were indeed produced in this vicinity.[21]

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

December 26, 2016

|

Last Updated

February 8, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Prof. Aaron Demsky is Professor (emeritus) of Biblical History at The Israel and Golda Koschitsky Department of Jewish History and Contemporary Jewry, Bar Ilan University. He is also the founder and director of The Project for the Study of Jewish Names. Demsky received the Bialik Prize (2014) for his book, Literacy in Ancient Israel.

Essays on Related Topics: