Edit article

Edit articleSeries

Moshe Greenberg: A Spiritual Critical Bible Scholar

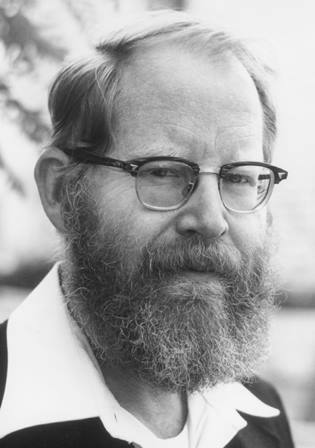

Moshe Greenberg, photo for the Israel Prize, 1994. Credit מיכה קירשנר (adapted). Yahrzeit 2nd of Sivan

Moshe Greenberg (July 10, 1928 – May 15, 2010) grew up in an observant household in Philadelphia; he was the son of Simon Greenberg, an influential Conservative rabbi and vice-chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary. He completed his Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania under Ephraim Avigdor Speiser, one of the great historical-critical scholars of the mid-20th century, who wrote the first Anchor Bible Old Testament volume, on Genesis. Greenberg also received rabbinical ordination from the Jewish Theological Seminary. He taught at the University of Pennsylvania until making Aliyah to Israel in 1970, and thereafter at Hebrew University until his retirement in 1996.

Looking at his alma mater and places of employment, it would not be obvious that the search for religious meaning would be part of Greenberg’s portfolio: Speiser? Penn? Hebrew University? These are people and places of scholarship and intellect, where the approach to the Bible is academic and historical; they are not usually associated with the soul, with religious understandings or spiritual implications of the text.[1]

For Greenberg, the study and teaching of Bible was about the search for meaning within and beyond the academic discipline.[2] He once wrote that Bible scholars should have “a sense of responsibility toward a community whose members, the scholars’ brethren, await their disclosure to them of the Scriptural message.”[3] In a slightly earlier piece, he compared the work of academic biblical scholars to that of theologians:

In his quest for significance… the holistic [Bible] interpreter partially resembles the theological exegete seeking timeless truth.[4]

Greenberg followed Yehezkel Kaufmann, arguing for an early, pre-exilic dating of P. But Greenberg was not particularly interested in source criticism per se. Rather, he saw his role as a scholar to illuminate the text as it has been read by generations of Jews (and others) since its redaction to final form (hence his term “holistic” in the quote above):[5]

To the history of the Bible upwards [i.e. source criticism] we need to add the history of the Bible downwards, which was primarily expressed through our commentators. In this later history is expressed the dynamic role of the Bible – the dialogue between the Bible and the generations.[6]

In other words, if we wish to make sense of the Bible as scripture, we can only do so by taking note of how the Bible has functioned as scripture.[7]

Greenberg’s Contributions to Biblical Scholarship

Greenberg co-founded and edited the prestigious critical commentary series Mikra Le-Yisrael, “Bible for Israel,” and wrote 10 books and over 200 articles over the course of his career.[8] Perhaps the most significant of his works were his commentaries on Chapters 1–11 of Exodus (Understanding Exodus, 1969) and Ezekiel (Anchor Yale Bible Commentary; volume 1 on Ezekiel 1–20, 1983; volume 2 on Ezekiel 21–37, 1997).

In these works, he does not ignore the sources and textual history that other scholars had uncovered, but he focuses primarily on the final, redacted form of the text, why it had been edited together into this final form, and what messages we should learn from that final form. For example, in his commentary on the Ten Plagues, he notes that the corpus is a combination of two pre-existing sets of seven plagues, but brings the reader’s attention to the meaning borne out by the new redacted structure and changes.[9]

Greenberg translated and abridged Kaufmann’s magnum opus The Religion of Israel (1960),[10] thus opening up Kaufmann’s approach to English readers. This work enabled the “early P” school of Biblical criticism, which is not just a technical matter but one that has major implications for how we see the development of Judaism and the relationship between Judaism and Christianity, to gain currency in the English-speaking world.

Bible as Religious Symbol

Central to Greenberg’s approach to the Bible was his approach to religious thinking in general. Influenced by Wilfred Cantwell Smith, a scholar of the Koran and comparative religion, Greenberg saw religious objects, acts, and texts as “symbols.”[11] A religious symbol is a physical object that both represents and activates an encounter with what Greenberg called “the transcendent realm”: a deeper understanding of the world, and the purpose of our lives in it; a sense of the world that responds to the innate human search for meaning.[12]

Greenberg argued for an approach to Jewish education in general that emphasized the symbolic aspect of Jewish acts, objects, and rituals.[13] Greenberg saw most aspects of Judaism as symbols in this way. Some of them are intuitively so: the lulav, the shofar, the mezuzah. Prayer. Blessings. On one level, they’re just plants, or parts of animals, or words. But we semiotically turn them into powerful symbols that represent and activate transcendence. Even the idea of God, for Greenberg, was a symbol.[14]

And, of course, text is a symbol. The Bible is a symbol, and that is how Greenberg wanted us to read it. In his view, human beings have innate spiritual needs, and sacred texts are one of Judaism’s central symbols that activate or represent transcendent responses to those needs. Interpreters and transmitters of those texts thus become by definition facilitators of religious meaning rather than just scholars and teachers.

Bible scholarship must, therefore, also be used in the service of a community of believers. Indeed, Understanding Exodus was originally commissioned from Greenberg by the Melton Research Center at JTS, to be used as a resource for Jewish educators in schools.[15] Bible scholars must not be concerned merely or only with the production of new knowledge “ex cathedra,”[16] but should enter into conversations with their fellow believers: “The lay reader is the scholar’s brother.”[17]

Biblical Prayer, Spiritual Language, and Wittgenstein

Greenberg’s approach to biblical scholarship is evident in his short book, Biblical Prose Prayer (1983), which contains the text of the Taubman lectures, a prestigious series of three lectures given at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1981–1982.[18] In the first two chapters, Greenberg argues—against the major trend of scholarly opinion at that time—that in ancient Israel, ordinary people regularly prayed to God in an extemporaneous, spontaneous fashion, following a uniform basic pattern of address, petition, and motivating factor, which derived from a similar pattern of human interactions:

In ancient Israel, in principle, anyone could pray. By this I mean that anyone capable of conventional interhuman discourse was capable of praying; equally, that the prayer of anyone was deemed acceptable to God.[19]

Greenberg’s analysis uses the tools, language, and conventions of academic biblical scholarship. In chapter three, however, he switches gears and, despite the academic context of the lectures, discusses issues that transcend the line between Biblical scholarship and religious leadership: If ordinary Israelites prayed regularly, suggests Greenberg, this would have had the effect of perpetuating the connection to the transcendent realm in their lives. The more an individual talks to God, the more they make God part of their vocabulary and daily comportment, the more sensitive they becomes toward the Divine in their life. Greenberg argues that ancient Israelites’ spontaneity in prayer created and sustained God’s presence in their consciousness.[20]

And then, functioning not just as Bible scholar but also as a rabbi-like figure offering spiritual guidance to his readers, Greenberg states:

We have only to look at the secular, prayerless scene about us to see how, in the absence of an orientation toward the transcendent, mundane concerns take sole possession of the field of consciousness.[21]

In that sentence, which would not sound out of place in a synagogue pulpit, Greenberg practices what he preaches and shows how a careful holistic study of the biblical text can address spiritual needs, can orientate us toward a realm of transcendence, and can enlighten us about the way we live our lives. He has leveraged his scholarship to what for him was a greater goal.

To those whose spiritual needs compel them to wonder how they can bring a sense of the Divine into their lives, Greenberg’s scholarly analysis opens up one of the Bible’s answers to this question: it suggests a נעשה ונשמע model which argues that by regularly praying (נעשה) in a spontaneous fashion, we will become more conscious or understanding (נשמע) of That to whom we pray.

Though, to my knowledge, Greenberg himself did not make this comparison, in my view, Greenberg is arguing for a Wittgensteinian approach to language and religion, in which the language that one uses about God creates a reality in one’s consciousness. In that sense, using Biblical Prose Prayer as a prism to analyze religious Jewish society today, I wonder if the increasingly common usage in some circles of phrases like baruch hashem (i.e., “blessed be God”), im yirtz’hashem (i.e., “If God wills”) and suchlike, serve the same function to those who use them as Greenberg argues was the case for spontaneous pray-ers in the Bible: the more you use that kind of language, the more it embeds a religious/spiritual consciousness in your mind.

The Value of Human Life

Greenberg’s article “The Biblical Grounding of Human Value” (1967) demonstrates his approach of using biblical scholarship to help his readers encounter the Bible as a religious symbol. Greenberg compares how the value of human life is treated in ancient Near Eastern cultures and biblical law.[22]

In the former, human life can be made up for with money or material; conversely, certain property offenses are capital crimes. Thus, in the ancient Near East, “life and property are commensurable,”[23] that is, able to be measured on the same scale; different in degree, rather than in kind. In contrast, the biblical-Judaic view holds that life and property are incommensurable—that is, they can in no way be interchanged or measured together.

He suggests that the Bible “places life beyond the reach of other values”; human life has a “uniqueness and supreme value.”[24] He continues:

The idea that life may be measured in terms of money or other property, and even more the idea that persons may be valued as equivalences of other persons is excluded.[25]

Because humans are made in God’s image, their lives are incommensurable with money. Thus money for bloodshed is impossible, and vice versa:

No offense against property is punishable with death. Breaking and entering, which the law of Hammurabi punishes by summary execution and hanging at the breach, is punished in biblical law with double damages.[26]

Greenberg’s analysis and ancient legal comparisons give the reader a profound moral insight into the Bible’s view of the infinite worth of human life. Because of Greenberg’s interest in the scriptural message to Jewish lay readers, he continues by examining later rabbinic elaborations on the theme of the infinite value of human life (in particular, the famous mishnah from Sanhedrin 4:5), and concludes with an arresting, prophetic, passion:

Of all the treasures of Judaism, there is scarcely one that deserves more publicity in our time than this emphasis on the value of the single human life… In the age of… impersonal and inhuman calculations, in an age which speaks in percentages, “tiny percentages” to be sure, of the victims of this or that experiment, or this or that supposed political and defense necessity, it is terribly important to emblazon before the eye of every man’s consciousness this unique, Jewish doctrine.[27]

Here Greenberg shows that spiritual meaning can be found through appropriate biblical scholarship.

The scholarly moves that Greenberg makes in the essay seem at first blush to be utterly conventional: comparison with Ancient Near Eastern parallel documents; an attempt to figure out the original meaning of biblical laws; even a brief note about earlier and later laws within the Pentateuchal sources. Yet, consistent with Greenberg’s approach, these scholarly moves are marshalled toward a meaning-oriented, homiletic goal.

TheTorah.com is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

We rely on the support of readers like you. Please support us.

Published

May 21, 2023

|

Last Updated

January 25, 2026

Previous in the Series

Next in the Series

Before you continue...

Thank you to all our readers who offered their year-end support.

Please help TheTorah.com get off to a strong start in 2025.

Footnotes

Dr. Alex Sinclair is Chief Content Officer for Educating for Impact, an organization that provides strategic and educational consulting to European Jewish communities, and an Adjunct Lecturer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He has taught, written and spoken widely on Jewish education, Israel-Diaspora relations, and Israeli politics in both academic and popular contexts. He was a professor of education at the Jewish Theological Seminary for almost two decades, and has also worked or consulted for a wide variety of other educational and communal institutions. His first book, "Loving the Real Israel: An Educational Agenda for Liberal Zionism," was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award in 2013. He lives with his wife and three children in Modi'in, Israel.

Essays on Related Topics: